This piece is from Fathom’s eBook The Life and Legacy of Yitzhak Rabin, which can be downloaded here.

The eBook also features essays and interviews by Reuven Rivlin, Uri Dromi, Luciana Berger, Omer Bar-Lev, Sara Hirschhorn, Ronen Hoffman, Tzipi Livni, Einat Wilf, Sir Martin Gilbert and Shlomo Avineri.

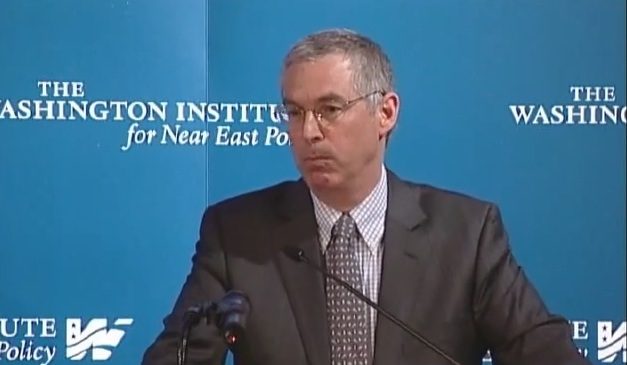

Toby Greene: Looking back on the life of Yitzhak Rabin, what stands out to you as his outstanding contribution to the State of Israel?

Michael Herzog: There are a number of outstanding contributions made by Yitzhak Rabin. First, in the realm of security, his contribution was very significant.

Rabin was a soldier, commander and a warrior. He began his career before the establishment of the State of Israel in the Jewish paramilitary forces, the Palmach and the Haganah. He was a commander of a brigade in the Haganah during the War of Independence, which played an essential role in securing the road to Jerusalem and ultimately allowing Israel to keep its capital in Jerusalem.

He then had a long military career before becoming the Chief of Staff of the Israel Defence Forces. Rabin was not only a warrior and a commander; he was a force builder who played a major role in the build-up, composition and training of the IDF. He had a deep understanding that for a military to win a war it had to be professional and to train constantly.

He really contributed to this becoming a part of the IDF’s DNA, leading to the unprecedented victory in the Six Day War.

When Rabin became prime minster he made another significant contribution in trying to reconcile Israel’s security needs and interests with an effort to bring about peace agreements with the Palestinians and to complete the cycle of peace with our immediate neighbours.

He signed a peace agreement with Jordan in 1994, securing peace on our longest border, and he tried very hard with Palestinians and Syrians. He epitomised a very unique combination of seeking peace while guarding Israel’s security interests. I think he had a deep understanding of the relationship between peace and security. He understood that peace does not automatically produce security, and it has to be fortified by solid security arrangements, and at the same time he understood that solid security arrangements contributed to peace. That combination makes him different to any of his successors.

Rabin was also one of the first to understand early on the nature of the Iranian threat to the State of Israel, specifically the existential threat of the Iranian nuclear programme. That developed a theme in his mind that for Israel to be better positioned to deal with this kind of threat, it had to try and complete the cycle of peace with its immediate neighbours – that’s a lesson that remains relevant to this very day.

It does not mean that Israel doesn’t have military or intelligence answers to the Iranian threat, but it would be in a much better position to deal with that threat if it had peaceful relations with its immediate neighbours.

TG: What was the significance of the assassination of Rabin to the peace process, though it continued after Rabin, would it have turned out differently if he had not been killed and why?

MH: This is a very hard question. It is impossible to tell how things would have developed had he not been assassinated and I say this because Rabin had a very difficult partner in Yasser Arafat.

Arafat – the leader of the Palestinian National Movement – in his heart did not recognise Israel’s right to exist as the nation state of the Jewish people. Arafat believed that in a very long historic process Israel would disappear and that the best way to deal with Israel should be through a mix of diplomacy and terror, as we saw through the years of the Second Intifada.

Nonetheless, I think it’s fair to assume that reality would have developed differently. When Rabin was at the helm, he navigated the peace process with very steady hand, epitomising a very unique mix of peace and security. His approach was very careful and very incremental. He did not believe in a major leap forward where you can break your head. He believed in a step by step approach and that after so many decades of hostilities and violence you have to test the ground and move on carefully.

He was respected by the Palestinians who knew that he would honour his word. They realised that he was not looking down on them but regarded them as partners, while strictly guarding Israel’s national interests. Rabin enjoyed the trust of the Israeli public and the international community, and was respected by the Palestinians. This was a combination which never repeated itself after Rabin.

If you ask me could Rabin have reached a permanent status agreement with Palestinians, I’m not sure, especially given Arafat’s attitude. I’m not sure that Rabin – with his mindset that a peace agreement should strengthen Israel’s security and not undermine Israel’s security – could have bridged all the gaps with the Palestinians. But I do believe that had Rabin stayed on long enough, the State of Israel would have been in a better place.

TG: Rabin in his life never talked about a Palestinian state as such, but do you think in his mind he recognised that that was the ultimate destination of any final status agreement?

MH: I think so, yes. He did not speak about a Palestinian state when I was part of the team negotiating under his guidance, and we were never told that this was the ultimate goal. But we understood that implicitly this is where it should lead to. The Interim Agreement that was signed under Rabin in 1995 actually defined the transition process to the negotiations on a permanent status agreement, so it was clear that when we reached that point of negotiating permanent status we would discuss a Palestinian state. He was very careful not to talk about it at the time and spoke of other types of solutions but I think everybody understood that if the Interim Agreement succeeds this was where it should lead to. Naturally if it doesn’t succeed then it doesn’t happen.

TG: Though aware of the risks, Rabin chose to attempt to pursue a path of negotiated coexistence with the Palestinians. Is there a way back to that path from the situation we’re in today and if so how?

MH: I’m very doubtful that in the foreseeable future we can go back to the same path of a negotiated deal. We had three major attempts at reaching a permanent status agreement resolving all the core issues between us and the Palestinians. One in 2000 between Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat at Camp David, one in 2008 between Olmert and Abu Mazen [Palestinian President Abbas], and the recent one in 2013-14 between Netanyahu and Abu Mazen, the so called Kerry led-process. We failed in all three of them and failure has a price. Failure has left scars with all participants and people have less and less faith and confidence in the future of the peace process and the prospects of reaching a breakthrough and ultimately peace between the parties.

To look back at how we negotiated you can see how things deteriorated over time. When Israel and the Palestinians negotiated permanent status agreements in 2000 and 2008 there were no preconditions for negotiations. In fact, Israel built much more on the ground then in terms of settlement activity than today. When we negotiated in 2013-14 Israel had to choose one of three preconditions: the release of political prisoners, a settlement freeze, or accepting the 1967 borders as the baseline for territorial negotiations and Israel chose the first.

If we negotiate today, we’ll meet all three preconditions and more; preconditions which will be very hard for any Israeli government to accept. So there is no confidence between the two leaderships and the gap between the two sides is widening.

There are many ideas about how to deal with this challenge, including a series of measures on the ground as well as new proposals that make use of the fact that we have converging interests with major Arab actors, to try and establish a regional architecture and regional context for dealing with Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They’re all very good ideas but, ultimately, to secure peace you will need Israelis and Palestinians to sit down and agree to it. It cannot be imposed from the outside.

This piece is from Fathom’s eBook The Life and Legacy of Yitzhak Rabin, which can be downloaded here.

The eBook also features essays and interviews by Reuven Rivlin, Uri Dromi, Luciana Berger, Omer Bar-Lev, Sara Hirschhorn, Ronen Hoffman, Tzipi Livni, Einat Wilf, Sir Martin Gilbert and Shlomo Avineri.

Comments are closed.