This piece is from Fathom’s eBook The Life and Legacy of Yitzhak Rabin, which can be downloaded here.

The eBook also features essays and interviews by Reuven Rivlin, Luciana Berger, Omer Bar-Lev, Michael Herzog, Sara Hirschhorn, Ronen Hoffman, Tzipi Livni, Einat Wilf, Sir Martin Gilbert and Shlomo Avineri

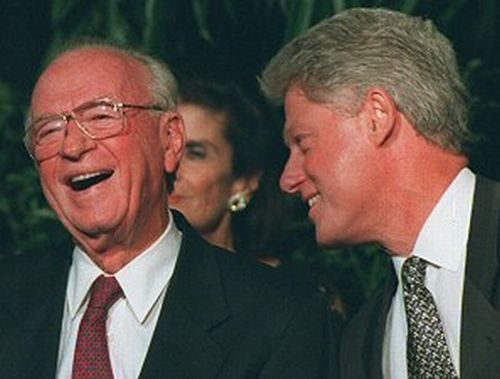

In an intimate account, Uri Dromi, who was foreign press spokesman to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, recalls the special qualities he saw up close that made Rabin an extraordinary statesman, and explains why Rabin set aside his own deep reservations in signing the Oslo Accords.

We flew to Washington for the White House signing of the Oslo Accords overnight, on an aging Israeli air force plane. It was the same plane Rabin and his staff usually took whenever he travelled as prime minister. His aides and the press were accustomed to uncomfortable nights cramped in their seats. Only Rabin, and his wife Leah when she travelled with him, had any comfort. The Prime Minister enjoyed a curtained off compartment with a bed. We would typically see him changed into pyjamas, saying goodnight, perhaps enjoying a nightcap, before disappearing into his compartment where he would sleep like a baby, arriving at his destination fresh and ready to work.

This flight was different. Rabin disappeared into his compartment as usual, whilst Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, who never seemed to sleep, worked the media at the back of the plane. But this time sleep did not come easily to Rabin. I saw him come in and out of his cabin, visiting the restroom, looking for another drink, clearly more agitated than normal. The following morning, as I watched his hesitant handshake with Yasser Arafat on the White House lawn, it struck me how deep his reservations were about the commitment he was entering into on behalf of the State of Israel.

The news of the Oslo Accords, and Rabin’s endorsement of them, came as a great surprise even to those of us working in his team. It was unlike him to enter into an agreement that would put an element of Israel’s security into the hands of anyone else, much less into the hands of the Palestinians and Yasser Arafat.

Rabin was ‘Mr. Security’, whose determination to deal with terrorism was beyond doubt. Indeed, his uncompromising attitude to terrorists made life difficult for me, as his spokesman to the foreign media. The most notable event in the early period of Rabin’s term was his decision to expel 400 Hamas and Islamic Jihad operatives to Lebanon. When the Lebanese refused to admit them, they were left stranded on the border, leaving us with a public relations disaster. In December of 1992 he convened his staff to consider whether doctors from the Red Cross should be allowed to visit them. Thinking of the international media I urged him to agree, but he was not impressed. “Will this bring to an end the Intifada?” he barked. It was a revealing moment for me. I understood he was only really interested in what was right for Israel’s security, and how things looked to the rest of the world was a much lower priority. But I also understood how concerned he was by the Intifada, and the need to bring it to an end.

Watching this leader – for whom Israel’s security was everything – make the transition from reluctantly accepting negotiations with the PLO, at the urging of Shimon Peres, to becoming sold on the Oslo Accords, was fascinating.

To key to understanding why he agreed to Oslo is another aspect of Rabin’s personality: his capacity to see the bigger picture. Even as Prime Minister in the 1970s, according to the account of then-Foreign Ministry Director General Shlomo Avineri, Rabin recognised even then the need to separate from the Palestinians to preserve Israel’s character as a Jewish and democratic state. However, in the immediate wake of the bruising 1973 Yom Kippur War, he did not feel that the time was right. Come the 1990s, Rabin saw an imperative to move forward and an opportunity. The context was the end of the Cold War, the decline of the Soviet enemy, and the rise of the new threats of Islamic extremism, which called for Israel build alliances with moderate states on its borders. Rabin also feared a decline of national resilience and sense of purpose within Israel, augmented by the corrosive effects of the First Intifada.

For Rabin the peace process was not something to come at expense of Israel’s security, it was a calculated risk intended to enhance Israel’s security in the long-run, given the changing nature of the threats both regionally, with the Palestinians, and within Israeli society.

Rabin’s ability to take fateful decisions for the future of his country in light of the bigger picture was one of the characteristics that marked him out from other political leaders. For those of us who saw him work at first hand, it was obvious that we were in the presence of as a statesman, as opposed to a mere politician.

His concern was always first and foremost what was good for the country. The matter of his own political survival – which preoccupies so many other politicians – was much less important for him. He did not enjoy the Knesset and hated managing party politics. We saw in his office how little time he gave to party figures, however much he may have needed them. For Rabin, what mattered were the affairs of state, and this is what he gave his time to. He poured into the details of every issue before coming to a decision.

For those of us working for him he was very tough, and could be hot tempered. If he was displeased with something you had done, you would hear about it. But he was never petty, and it was never personal. His integrity shone through for everyone he dealt with, including the Palestinians and Yasser Arafat, who I believe regarded Rabin with a mixture of respect and even fear.

His natural discomfort with masking the truth made his encounters with the foreign press an interesting experience. When I would bring leading international journalists to be briefed by him, I could always tell when he was obscuring something because he would noticeably blush.

Statesmen of Rabin’s stature are rare in politics today. But I believe that the basic conclusion Rabin reached about the need to separate from the Palestinians is now clearer than ever. The necessity for Israel to return to a proactive path to change the status quo will, I believe, ultimately generate an Israeli leadership ready to emulate Rabin and take the tough decisions.

This piece is from Fathom’s eBook The Life and Legacy of Yitzhak Rabin, which can be downloaded here.

The eBook also features essays and interviews by Reuven Rivlin, Luciana Berger, Omer Bar-Lev, Michael Herzog, Sara Hirschhorn, Ronen Hoffman, Tzipi Livni, Einat Wilf, Sir Martin Gilbert and Shlomo Avineri.

Comments are closed.