2017 is the hundredth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, the British government’s letter of support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Toby Greene argues that Britain should use the spotlight to promote a positive vision for the future, using a vocabulary that is sensitive to the conflicting emotions on both sides of the dispute, and ‘it’s best endeavours’ to improve the chances of the pragmatists who recognise that two national homes is the only way to reconcile the demands of two nations, and end a century of conflict.

Prime Minister Theresa May declared at a speech to the Conservative Friends of Israel on 12 December that this year’s centenary of the Balfour Declaration would be marked by Britain ‘with pride’.

This sets out an important marker for how Britain will handle an anniversary which, let’s face it, must look to many in Whitehall like one big headache. Not a word can be spoken about the document – which left indelible British fingerprints all over the Jewish-Arab struggle in the Middle East – without angering someone, or several million someones. Ministers could be forgiven for wanting to hide under the bed until it’s all over.

But the anniversary, and Britain’s historical legacy, cannot be avoided. For Jews around the world the Balfour Declaration, and its role laying the groundwork for the establishment of Israel, is something to be celebrated with pride. Whilst for the Arab and wider Islamic world, and for Palestinians in particular, the Balfour Declaration is a mark of shame against the British. The Palestinian Authority has threatened to sue Britain for its ‘crime’, and anti-Zionist campaigners will seek to tar Zionism, once again, with the brush of imperialism and colonialism.

How then should British politicians and leaders handle this thorny subject this year? What is a reasonable and balanced way to relate to, and talk about, the Balfour Declaration one hundred years on?

Millions of words have been written, and millions more will be written, about what the Balfour Declaration was about from a British perspective, seen through the lenses of Britain’s ambivalent relationship with its imperial and colonial past.

What British leaders across the spectrum need to recall in the face of the conflicting emotions of Jews and Palestinians and their respective supporters, is what the Balfour Declaration means for the nations whose destiny it has touched.

For Jews, the Balfour Declaration is part of its narrative of salvation. Simply put, hundreds of thousands of Jews who fled from Europe to Palestine in the 1920s and 1930s, and their descendants, owe their lives to it. The family members they left behind perished in the Shoah (Holocaust). For Jews it is the 1939 White Paper, in which Britain cancelled its commitment to a Jewish national home, all but halted Jewish immigration, and closed off one of the last escape routes from the Europe, that is the mark of British betrayal and shame. These events touched most Jewish families in Britain in one way or another.

Not only did the creation of the Jewish national home provide a refuge for hundreds of thousands of Jews before the war, but it enabled the establishment of the State of Israel after the war. For Jews, Israel’s establishment – restoring Jewish sovereignty in what Jews consider their historic homeland – was the anti-Shoah, giving Jewish identity a positive future.

By understanding this, it can it be appreciated how clankingly offensive the demands for Britain to apologise for the Balfour Declaration are for Jews. Though perhaps understandable from Palestinians, from others it reflects a conspicuous disdain for Jewish sensitivities and Jewish history. It is no surprise that a recent Parliamentary event launching a ‘Balfour Apology Campaign’ became a shameful forum for antisemitic bluster.

That said, everyone who cares about Israel must also recognise that the process that created the State of Israel – the Jewish narrative of salvation – is for Palestinians their narrative of catastrophe, or ‘Nakba’. The extent to which the declaration is responsible for their loss is open to historical debate, but the loss and suffering of the Palestinian people is undeniable.

This is the minefield that Britain must navigate, and a notable gap has already emerged between Number 10 and the Foreign Office. May’s commitment to mark the anniversary with pride jars with the position taken by Middle East Minister Tobias Elwood in a recent Parliamentary debate, in which he declared that Britain will mark the centenary, but ‘will neither celebrate nor apologise’.

Certainly the answer for British representatives is not to attempt to retrospectively rewrite the Balfour declaration, as Elwood awkwardly appeared to do in that debate, stating that the Balfour Declaration should have asserted the political (rather than only civil and religious) rights of the non-Jewish communities in Palestine.

Redrafting a century-old letter to assuage today’s political sensitivities can only distort the historical picture. Rather than rewrite the past, Britain should use the spotlight to increase understanding of it, and promote a positive vision for the future, using a vocabulary that is sensitive to the conflicting emotions on both sides of the dispute.

1917 and all that

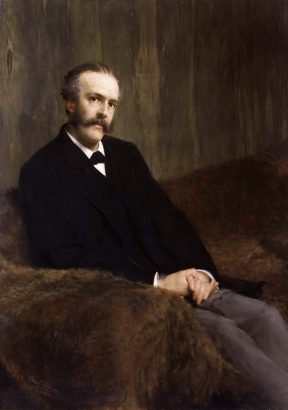

Arthur Koestler witheringly summarised the Balfour Declaration as document in which ‘one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third’. This is pithy, but no more helpful as a history than the Zionist slogan of ‘A land without a people for a people without a land’. A balanced account of the origins of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict requires looking simultaneously at two overlapping but different perspectives: of Jewish-Zionists and Palestinian-Arabs. It is like staring at stereogram. If you can avoid going cross eyed and getting a headache, a picture with depth begins to emerge.

Zionism as a modern political movement gained momentum at the end of the nineteenth century as a result of the failure of the Jewish emancipation to end antisemitism in Europe. The founder of political Zionism Theodor Herzl witnessed as a journalist the 1895 Dreyfus trial, in which a French Jewish army captain was falsely convicted for spying and publicly disgraced before a Parisian crowd chanting ‘death to the Jews’. Meanwhile in the Russian empire Jews were scapegoated for political unrest, and subject to waves of murderous antisemitic riots and punitive legislation restricting their freedoms.

In his famous pamphlet. ‘The Jewish State,’ Herzl lamented the fact that ‘we have honestly endeavoured everywhere to merge ourselves in the social life of surrounding communities and to preserve the faith of our fathers. We are not permitted to do so.’ His plan was, ‘perfectly simple … Let sovereignty be granted us over a portion of the globe large enough to satisfy the rightful requirements of a nation; the rest we shall manage for ourselves’.

Herzl was not the first to reach this conclusion. It was hardly surprising in a Europe filled with ethnic, cultural and linguistic groups seeking national self-determination, that Jews would seek the same solution to their own situation.

Indeed, a movement to establish modern Jewish settlements in Palestine had begun in the Russian empire in response to a wave of pogroms of 1881. Whilst hundreds of thousands left the empire to find new homes – mostly in North America but also in Britain and other places – a smaller number went to the ancient homeland known to Jews as the Land of Israel, inspired by the vision of a new Jewish centre of life where Jews could emancipate themselves.

The territory they reached was an underdeveloped and relatively underpopulated part of the Ottoman Empire. Though the area was known as Palestine, there was no such place on the Ottoman administrative and political map, being divided into various smaller administrative units, and its half million Arab inhabitants had no notion of Palestine as political unit or ‘Palestinian’ as a national identity. There was a small, educated, urban Arab elite, but most of the population were rural tenant farmers or Bedouin, with illiteracy estimated at 95 per cent.

Life in Ottoman Palestine was harsh. Many Jews gave up; some died. But this unpromising territory is central to the Jewish collective identity, being at the core of its biblical and historical narrative, its theology and daily liturgy. And it was over this territory that the Zionist movement lobbied the great powers for a charter to establish a Jewish state.

By the outbreak of World War I, the Jewish population of Palestine had swelled from around 20,000 to around 90,000: buying land; establishing agricultural communities, including kibbutzim; and building new towns, like Tel Aviv. This was the original start up nation. Leon Pinsker, one of the early Russian-Zionist ideologues, called it ‘Auto-emancipation’. However, by 1914 Jews were still a small minority, with Arabs numbering around 590,000.

Why Russian-born chemist Chaim Weizmann and his small group of British Jewish supporters was successful in convincing the British cabinet to back the idea of a Jewish national home in Palestine in 1917 is the subject of endless historical curiosity, especially given how much of a burden this promise later seemed. Did ministers hope, as they claimed, in their desperation to break the tie in the Great War, that the support of American and Russian Jewry would strengthen their positon? Were they swayed by altruistic motives, recognising the plight of world Jewry? Were they inspired by biblical prophecy of the Jewish people’s restoration to their land? Did they hope for a reliable British dependency to hold key strategic ground protecting Suez, Haifa and the overland routes to the Gulf, and to keep at bay the French and Russians?

Whatever their motives, they carefully considered the wording, with the outcome a masterpiece in brevity, but also ambiguity. The goal was vague with respect to geography and political status: ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.’ The British commitment was imprecise: ‘to use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.’ And there were caveats: ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’, intended to satisfy pro-Arab voices; nor to prejudice ‘the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country,’ to satisfy non-Zionist Jews in Britain who feared harm to their status as equal British citizens.

Nonetheless, for Zionism the declaration was a game changer, not because it was unique as a statement of support: French and American leaders also expressed support for Zionism, but because the outcome of the war made it possible for support became policy. Within weeks of the declaration, General Allenby has captured Jerusalem. The British commitment to the Jews was upheld in the post-war peace settlement, and transformed into an internationally endorsed legal Mandate by the League of Nations.

Promises and betrayals

Whether or not this was wise policy for the British, it was the opportunity for the Zionist movement, and they took it. Under the protection of the British sovereign and backed by international law, the Zionist movement spent the next twenty years establishing the foundations of a Jewish state: buying and cultivating land; bringing in Jewish immigrants; building communities; developing industries; establishing social services and cultural institutions. They absorbed waves of new immigrants leaving behind discrimination in Europe. A great surge of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany in the 1930s buoyed the Jewish population to around 350,000 by 1939, around one third of the population.

Yet in the Arab world, the Declaration came universally to be seen as a case of British betrayal and double dealing: evidence of Western disregard for Arab rights and even a cynical agenda to keep the Arabs weak and divided. The British had made a separate commitment in 1915 to Hussein the Sharif of Mecca, to support his aspiration for an independent Arab kingdom in return for his rebelling against the Turks. This commitment was also laced with ambiguity and qualification, explicitly excluding regions that ‘cannot be said to be purely Arab’, but imprecisely describing their geographical extent. These commitments were complicated by a third agreement between Britain and France, to divide the Ottoman territories of the Middle East into areas of their control and influence.

Whether or not the promises were consistent with one another is debated by historians. It is worth recalling of the three agreements, only the Balfour Declaration was not a secret, being issued in a letter that was intended to be made public.

After issuing the Balfour Declaration, the British tried to reassure Hussein, and even brokered a signed agreement between Chaim Weizmann and Faisel, Hussein’s son and representative at the Paris peace conference, in which each committed to support the aspirations of the other.

How the two movements were to be reconciled remained unclear. As Colonial Secretary in 1922, Churchill tried to draw a line under the matter by drawing a line in the sand. He partitioned Palestine along the Jordan River, and barred Jewish settlement east of the river, where he created Transjordan as he would later boast, with ‘one stroke of a pen, one Sunday afternoon’. Allowing Faisel’s brother Abdullah to rule it, he considered the British commitment to the Sharif and his sons with respect to Palestine fulfilled.

Of course Abdullah was not fulfilled, cut off from Jerusalem, and frustrated in his aspiration to lead an Arab kingdom of greater size and significance. But the more immediate concern was the majority Arab population of the area now defined in international law as a Jewish National Home. Arabs in Palestine had a mixed response to the arrival of Jews at the turn of the century. But unease at the threat to their political and economic position grew in parallel with the size of the Jewish community, and with the increasing influence of nationalism in the Arab world. As the Ottoman Empire collapsed, Arab nationalists in Palestine hoped that they would become part of newly formed wider Arab state, most likely part of a greater Syria. But the publication of the Balfour Declaration, and then the loss of Syrian independence to French control in 1920, catalysed the emergence of a distinct Palestinian national identity, of which resistance to the establishment of a Jewish national home was a core component. From then on, Jewish and Arab claims to sovereignty in the territory west of the Jordan River were irreconcilable.

Arab resistance to British rule and Jewish settlement burst into increasingly bloody rounds of violence over the 1920s and 1930s, culminating in a broad based Arab revolt in 1936. In 1937 the British proposed reconciling the two competing populations by partitioning Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states – the first emergence of what today we call the two state solution. Jews were open to partition, albeit rejecting the proposed borders, whilst the whole enterprise was rejected by the Arab side.

By 1939, with war in Europe looming, the British decided, in Chamberlain’s words, that it was better strategy ‘to offend the Jews rather than the Arab’. To calm the Arab revolt and placate surrounding Arab states, it issued its White Paper capping Jewish immigration.

Six years later, two in every three Jews in Europe had been murdered, six million in total. For their survivors, living in displaced persons camps across Europe, their hope for salvation was invested in the promise for a new life in the new Jewish society in Palestine. But the British barred Jewish entry, turning back refugee ships like the famous ‘Exodus’. With 100,000 British troops struggling to keep control in Palestine, the British gave up, turning the issue over to the newly formed UN, whose commission proposed a two state solution. The proposed borders satisfied no-one, but the Jews reluctantly accepted the compromise, whilst the Arabs unequivocally rejected it.

The War between the two communities that followed led to the flight and displacement of around 600,000 Arabs. Their descendants today number in the millions. Many remain stateless. Who was to blame for their flight, and for the perpetuation of Palestinian refugee status is a dispute where history intertwines almost inseparably with the political dispute. What is beyond debate however, is that for Palestinians the ‘Nakba’, is a defining moment in their national identity. The key is the symbol of the homes they lost. From their perspective, their land was taken from them by the Jews, and British imperial power made it possible.

What to say?

At the time of the Balfour Declaration, the idea of a Jewish nation state divided Jews, after the Holocaust, it united them. According to a 2015 survey of British Jews conducted by City University, ‘The vast majority of our respondents support its right to exist as a Jewish state (90 per cent), express pride in its cultural and scientific achievements (84 per cent), see it as a vibrant and open democracy (78 per cent) and say that it forms some part of their identity as Jews (93 per cent).’ No wonder that the Balfour Declaration, and the British role in laying the groundwork for the State of Israel is something that British Jews want to celebrate with pride.

But equally, it is little wonder that this is something that Palestinians and their supporters want to denigrate. At this moment the Palestinian voice and narrative should also be heard.

Reconciling these voices however, cannot be done in the past. That is why Britain should take the opportunity of the spotlight to speak about the future. The Balfour Declaration was a statement of aspiration. It declared what Britain viewed with favour, and what it would use its best endeavours to bring about. What should Britain view with favour today?

Firstly, that with Israel’s establishment, centuries of Jewish homelessness and persecution have ended; that Israel is democratic, affirms the rights of non-Jewish citizens, and is an extraordinary engine for creativity; and that it has a fruitful relationship with Britain based on shared interests and values.

But Britain should also view with favour – indeed reaffirm with vigour – the urgency of establishing a Palestinian state that would afford long overdue self-determination, due dignity, and economic and political opportunity to the Palestinian people.

Perhaps most importantly, it should affirm that these goals are mutually reinforcing. The surest way to secure Israel’s future as a Jewish national home – in terms of demography, security, and legitimacy – is through the creation of a separate Palestinian state. Many Israeli politicians, including at times Prime Minister Netanyahu, have acknowledged this. At the same time, a conflict ending agreement will require the Palestinians to agree to a refugee solution that is consistent with two states – two ‘national homes’ – for two peoples, and does not undermine Israel’s Jewish character.

Yet Britain must also recognise that today, it does not have the power to carve borders in the desert and create states with the stroke of a pen on a Sunday afternoon. Those with the power to determine the fate of the Jewish national home and the Palestinian national home for the generations to come are the two populations themselves. In that respect, all peoples can draw inspiration from what the Zionist movement achieved. The Balfour Declaration created the opportunity, but it was the endeavour of the Jews themselves who built the groundwork for what many had previously thought impossible, a fully sovereign Jewish state. Seeing a piece of paper turn into a living state is an invitation to all peoples, Israelis and Palestinians alike, to become authors of their own destinies.

The future will be shaped by Israelis and Palestinians. Britain should use ‘its best endeavours’ to improve the chances of the pragmatists among them, who recognise that two national homes is the only way to reconcile the demands of two nations, and end a century of conflict.

As a volunteer at the Wiener Library, I am currently working on preparing an archive relating to the recruits to the Jewish Relief Unit for use by researchers. The JRU started recruiting workers as early as 1943 for work with what became known as “Displaced Persons” (in this case, Jews) after the war. These were an eclectic mixture of (mostly Jewish) British natives and emigres. What is fascinating to me is the number of these workers who, after their period of employment ended, moved (after May 1948) to Israel, often accompanying their charges – frequently relatively large groups of “unaccompanied” (i.e., orphaned) children.

One such worker notes, in a letter back to the JRU, that her charges, some 300 in number, although they knew that faced hardship and struggle ahead, were delighted not to be “back there”.

Even at this distance from the Shoah, I cannot regret the Balfour Declaration and the end it brought. Nor should we forget who accepted, however reluctantly, the terms of the UN Resolution of 1947 and who not only rejected it, but attempted to drive the Jews of the Yishuv into the sea after the passing of the Resolution.

And as for “[t]he surest way to secure Israel’s future as a Jewish national home – in terms of demography, security, and legitimacy – is through the creation of a separate Palestinian state”, perhaps the great powers, whoever they are considered to be, should be stressing that to the Palestinians and their sponsors, rather than wasting their efforts on attacking the Declaration and demanding a British “apology”.

One can but hope.

What does one have to do to gain access to the ability to print your articles for my use, i.e. one copy? bill franks

Hi William,

Thanks for your comment. On the left hand side of the page, directly under the author name and bio, there are 5 options, of which the last is the print option. Best, Fathom

Mr. Greene : You have written an interesting article but I feel that it falls foul of selective use of evidence and the result is a distortion of the Balfour Declaration.

You write that the Jews were divided over the issue of a state for the Jewish “nation” (when did one “a nation of Jews” ever exist?). Why then do you use 21st C. survey results to demonstrate approval in support of the state of Israel? You are selective in your use of facts so that they suit your cause. The Balfour declaration is an historical document and needs to be analysed within that context.

You also claim that the Declaration was “a statement of aspiration” and that Britian would use its “endeavours” to bring it about. Why did you not mention that a “homeland” for the Jewish people was not a state? Why did you not mention that according to international law a “homeland” is not a “state”? Once again you are being selective in your analysis.

Finally, you conclude that the Declaration was fulfilled, despite the fact that a “state” was nowhere in the wording, and that it evolved out of ethnic cleansing aided by the brutalisation of the indigenous Palestinians (although you do not mention these facts) to set up Israel. You then invite the Palestinians to follow this path!!

Many times when one reads an article or analysis of events the reader should take into account what is said and used as evidence by the writer to persuade the readership of their interpretation. However, what is often more important is what is not said and included by the writer and that is the case regarding this article by Greene.

The Balfour Declaration was to create a “homeland” for the Jewish people “in” Palestine. Since when is a “home” a state according to international law? Since when is a “home” synonymous with a state?

Another point which was not included by the writer was the fact that the Mandate was to establish a state for the indigenous peoples of the territory called Palestine. Throughout the mandate period the majority were always the Palestinian Muslims and the Palestinian Jews were always the minority.

“Striking a balanced tone so often missing from current debates”… was written in the Editorial regarding this article. I agree with the principle but the writer has not fulfilled this ideal. The Balfour declaration, however, was, and is, abused to support Zionist/Jewish actions which became part of the root problem regarding the present day situation.

To Mr Jonathan Gray,

I respectfully suggest that you read the magnificent and erudite thesis of the French-Canadian International and Human Rights Lawyer, Dr Jacques Gauthier, who spent 26 years on the subject. The indigenous people of this area of Judea and Samaria, is the Jewish people, who were ethnically cleansed by many foreign colonialists,including the Arabs from the 7th century. No other people have ever had sovereignty in Judea and Samaria. They were all foreign colonialists.

Sovereignty over the Old City of Jerusalem by Dr. Jacques Gauthier

Dr. Gauthier’s comprehensive thesis entitled Sovereignty over the Old City of Jerusalem was completed in 2006 at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. He has served as legal counsel to various governments including the governments of France, Spain, Mexico and Canada. In 2000 he was knighted by the government of France as Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite. Dr. Gauthier has been involved in the pursuit of human rights in China, Afghanistan, Zimbabwe, Myanmar and Canada. He has served as the Vice Chair, Acting Chair and President of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (Canada).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VH5pD3yVH64&t=1632s

It is greatly disturbing that you even deny the existence of a Jewish nation, yet write about a Palestine that never existed. The word is not Arabic; it is Roman and was invented by Emperor Hadrian in 135, when he wanted to erase Jewish history and the connection between the Jewish people and the land of Israel. The same is true today. Hadrian took the Hebrew for Philistine, a sea-faring people from the Aegean Sea and “Latin-ised” it to make Palaestina. Hadrian then renamed the geographical areas called Judea and Samaria, to “Palaestina.”

Until 1964, Palestinians were Jews. It was only after the former USSR, reinvented Yasser Arafat, born in Cairo, Egypt, as leader of the “Palestinian people” that there became a concept of Palestinian-Arabs. The UN did not use the word “Palestinian” in their documents until after 1964. The PLO was also invented in 1964 – given there were no “Settlements” or so-called “Occupation” until after 1967,what was to be “Liberated?” The answer is clear from the 2 PLO Charters of 1964; and 1968.

The Arabs are very clear:

There is no such country as Palestine. “Palestine” is a term the Zionists invented. There is NO Palestine in the Bible . . Palestine is alien to us.”

AWNI ABDUL-HADI, Peel Commission Testimony, 1937.

“There is no such thing as Palestine in history. Absolutely not.”

DR. PHILIP HITTI Anglo-American Committee Testimony, 1946.

“It is common knowledge that Palestine is nothing but southern Syria.”

Saudi Representative to the UN, 1956.

“Never forget this one point: There is no such thing as a Palestinian people. There is no Palestinian entity . . . Palestine is an integral part of Syria.”

HAFEZ AL-ASSAD to YASSER ARAFAT

Zuheir Mohsen: there are “no differences between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese”, though Palestinian identity would be emphasised for political reasons. This originated in a March 1977 interview with the Dutch newspaper Trouw:

“Between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese there are no differences. We are all part of ONE people, the Arab nation. Look, I have family members with Palestinian, Lebanese, Jordanian and Syrian citizenship. We are ONE people. Just for political reasons we carefully underwrite our Palestinian identity. Because it is of national interest for the Arabs to advocate the existence of Palestinians to balance Zionism. Yes, the existence of a separate Palestinian identity exists only for tactical reasons. The establishment of a Palestinian state is a new tool to continue the fight against Israel and for Arab unity.

A separate Palestinian entity needs to fight for the national interest in the then remaining occupied territories. The Jordanian government cannot speak for Palestinians in Israel, Lebanon or Syria. Jordan is a state with specific borders. It cannot lay claim on – for instance – Haifa or Jaffa, while I AM entitled to Haifa, Jaffa, Jerusalem and Beersheba. Jordan can only speak for Jordanians and the Palestinians in Jordan. The Palestinian state would be entitled to represent all Palestinians in the Arab world en elsewhere. Once we have accomplished all of our rights in all of Palestine, we shouldn’t postpone the unification of Jordan and Palestine for one second.

Zuheir Mohsen, military commander of the Palestine Liberation Organization, said after the 1967 Six Day War: “There are no differences between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese. We are all part of one nation… yes, the existence of a separate Palestinian identity serves only tactical purposes.

The founding of a Palestinian state is a new tool in the continuing battle against Israel.”

In 2012 the Palestinian Authority’s Minister of the Interior and of National Security Fathi Hammad said: “Half of the Palestinians are Egyptians and the other half are Saudis.”

To : RM Share.

Thank you for your comment.

You write about soverignty and how the Jews are the (only) indigenous peoples of the territory and, therefore, entitled to the land. Israel as a country/state did not exist for over two thousand years and your “historical argument” holds little or no weight in international law. There are numerous countries throughout the world that could make similar claims across the globe and that would lead to chaos and conflict. Following your line of thought further, Italy could lay claim to Spain, France and England but they don’t. They realise the ridiculousness of that line of thought and its lack of legal backing.

You then try to deny the existence of the people called Palestinians but there are numerous references to the people called “Palestinians”. Read what Herodorus wrote about them in the “Histories”. They inhabitied a vast territory and today, a small part of that land where the Palestinians lived for thousands of years, holds the state of Israel.

The British held the legal Mandate for Palestine. They defined who was indigenous and who was not. Their definition favoured the influx of colonial Zionists/Jews from Europe. Despite this bias the Palestinian Muslims held the majority throughout the Mandate period. The British established Palestinian Passports, Palestinian Magistrates, Palestinian Courts and so forth. The territory was desnigated for the establishment of a state for the indigenous Palestinians in which the Jewish colonialists were to have a homeland, not a state.

You then make numerous references to cast doubt over the existence of Palestinians but what you are quoting are just opinions and have cherry picked your references. One needs to know your quotes wihin a broader context , showing what was said before and after those statements and to find out if there are political motives for such claims etc. etc. Finally, Palestinians as a people have been recognised as such by International law.

You finish by claiming that “The founding of a Palestinian state is a new tool in the continuing battle against Israel.”

However, the indigenous Palestinians rightfully and legally are entitled to statehood. Whether what you say is true or not, they have the legal right to a state and the territory the pertains to this is all of the West Bank and Gaza.

You might want to check out Martin Kramer’s article at Mosaic from June 2017. The largest thing Kramer does is shatter the myth that the Balfour Declaration was a unilateral action by Britain. In actuality, the Balfour Declaration was supported by all of the Allied powers plus the Vatican.

The reason history came to believe that Britain unilaterally issued the Balfour Declaration was because the international support for it was secured entirely by Nahum Sokolow whereas Britain’s support was secured in part by Weitzmann. Two factors then led to attributing the Balfour Declaration entirely to Britain. One is that in the inter-war period, after the San Remo Conference secured the Jewish homeland in the British Mandate, the other Allied powers lost interest in reconstituting the Jewish home and all efforts were focused on appealing to Britain’s conscience to live up to its commitments as the Mandatory power. The second is that Weitzmann sought sole credit for the Balfour Declaration, and thus had to exclude every part in what he made no contribution, thus writing out the diplomatic effort to gain Allied support.

Mr Gray,

Sadly, you have not addressed my points but have merely dismissed them as if swatting flies. It is not possible to write an essay via a comment, but I referred to 2 particular points.

First, I refer to the work of Dr Jacques Gauthier who, based solely on international law, cogently argues that the only people who have sovereignty in Jerusalem and therefore Judea etc are the Jewish people. I suggest you read what he has to say because it is based solely on international law. A summary can be found in his lectures on YouTube. His Ph.D thesis was granted by the University of Geneva and it is curious you ignore him.

Second, you replied as if I stated that calling for a state is yet another ploy to destroy the Jewish state. I did not. It was Zuheir Mohsen of the PLO.

As for the word “Palestinian”, until 1964, Jews were referred to as “Palestinians.” In 1964, the former USSR/KGB reinvented Yasser Arafat, born in Cairo, Egypt, as “leader of the Palestinians!” The word Palestinian was only used in UN documents from 1970.

Syrian President Hafez Assad to Yasser Arafat: “There is no such thing as a Palestinian people, there is no Palestinian entity, there is only Syria. You are an integral part of the Syrian people, Palestine is an integral part of Syria.”

Palestinians are a myth says Hamas member “they are just Saudis and Egyptians”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XwBSWN4s9JU

Dismissing what the Arabs actually say in Arabic is somewhat curious on your part. It is incontrovertible that during the Mandate period, the British allowed illegal Arab immigration. It is also true that the Arabs migrated because of the improvements undertaken by Jews from the First Aliya onwards, that drained the swamps of malaria and made the desert bloom.

The Jewish state has been under attack before there was a Jewish State. The issue has never been about land or the Arabs wanting another (23) state. If that were true, why did the Arabs reject a state in 1937 (Peel Commission & Partition) and the UNGA Partition Plan of 1947. Instead, the Arab League promised “a war of extermination and a momentous massacre” and illegally invaded the nascent state of Israel, in May 1948, with the intention of eliminating Israel. History also shows that the self-appointed Arab leader and British appointed Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, was an antisemite and pro-Nazi supporter. Between 1941-45, Husseini was a guest of Hitler in Berlin, where he met Himmler and Eichmann and planned the extermination of the Jews in the Middle East (and also in Europe). The Middle East was to be free of all Jews. There is documentary evidence showing the alliance between Husseini and Nazi Germany.

Moreover, during the illegal occupation of Gaza by Egypt and the illegal occupation of part of Judea by Jordan, 1949-1967, the PLO did not make any attempt to demand a state. There are 2 points here. First, if the “Occupation” only occurred after 1967, what was there to “liberate” in 1964? The answer is the whole of the Jewish state. Second, the 6 Day War of June 1967, led to Israel’s suing for peace. At Khartoum the Arab League replied: NO recognition of the Jewish state. NO negotiations; and NO peace. The PLO decided to rewrite its Charter and the 1968 Charter now declared that what Jordan and Egypt illegally occupied, should be part of “Palestine.”

There are 22 Arab states occupying over 99.9% of the Middle East, The Arabs have refused 7 offers of a state. Murderous attacks on Jews began from 1919 onwards. Jews are at best second-class “dhimmis” and according to the Arabs (in Arabic), when they defeat Israel and replace Israel with “Palestine” all of this will simply be part of a Muslim Caliphate, a Judenrein Middle East.

I did not say this: the Arabs do.

The Balfour Declaration was a statement that expressed British interests at the end of the First World War – a British desire to conquer the Middle East and distance Ottoman Turkey away. It was a pay back to the Zionist Jews who helped Britain to advance their political interests in the US and helped in the war itself, not only in Palestine but also in Europe.

Since the Arabs in the Land of Israel never accepted the right of the Jews to establish a national state for themselves in the Land of Israel, and did not accept the Balfour Declaration; and since Britain quickly betrayed the idea of the document, this document lost its current significance, leaving only a historical document that expressed a historical view point of its time – a not more than two years’ time, until the British partitioned Palestine and gave its Eastern bank, Trans-Jordan, to an Hashemite Saudi Emir, while the Western half, between the River and the Sea, became a British colonial stronghold which reduced Jewish rights, restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine by certificates procedure, and opened the country to free Arab immigration flow from surrounding states and area. From the end of the 1920s, all Western countries prevented the emigration of Jews out of Europe, thus contributing to the increasing the number of Jews that later will be slaughtered by the Nazis during World War II.

Zionism started before Balfour declaration and Israel was created along the war that was imposed unto her by Arab coalition. The declaration was only a promise never implied and realized.

On some future occasion publish the story of the Government of All Palestine declared in Gaza by the Mufti Haj Amin al Husseini -Arafart’s uncle – on 15th Sept ’48 NB the date but five months late. If the Arabs of Palestine do not have their state yet it is because they could not run their political trains on time and the Arab governments of 1948 – 67 did not want a Palestine state of any sort and sabotaged it – Nasser sending the Mufti to Beirut in ’58 where he died in political irrelevance years later. Then Syria started Fatah and Egypt started the PLO in order to subvert and bag Jordan between them. Then they fell into the trap of their own bombast in 1967.