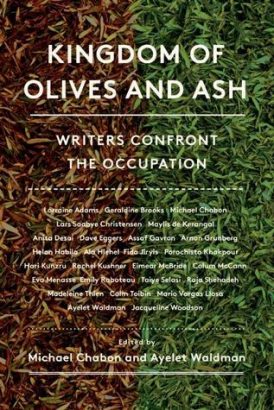

Kingdom of Olives And Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation, edited by Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman, is a new 400-page book released by Harper Perennial on 30 May in conjunction with the Israeli NGO Breaking the Silence. Breaking the Silence was formed in 2004 by former IDF soldiers who oppose the occupation of the West Bank and war in Gaza by testifying about their experiences in both arenas. The organisation has been devoted to publishing book-length, first-person but anonymous accounts of military action in Gaza and the West Bank, but Kingdom of Olives and Ash accomplishes something very different. It gathers 26 essays by an international group of writers who recount their 2016 and earlier visits to the West Bank or, in one case, to Gaza.

Breaking the Silence invited these writers to come to Israel and write about what they saw and heard. They travelled together in small groups, sharing some experiences and having some unique encounters. The contributions were not edited for content, a decision that is understandable, though either the introduction or the afterword could have added clarifications or suggestions for productive political engagement. What is distinctive about the book is that it personalises the Palestinian experience of the occupation. As these are accomplished writers, their essays are often eloquent and compelling. Although it is impossible to estimate how much of the book the average person will read, the odds are that it will have significant impact. A book tour is under way that will help make that more likely.

Kingdom tells the stories of numerous Palestinians who struggle to achieve their ambitions while enduring constraints or humiliations imposed by Israeli authorities. As Michael Chabon puts it in his chapter, ‘As long as you were willing to accept, consciously and unconsciously, the arbitrariness that governed every aspect of your life, you could actually get something done.’ (53) The title character of Chabon’s ‘Giant in a Cage’ is one Sam Bahour, an American of Lebanese Christian descent who moves to the West Bank and spends years devoted to establishing Ramallah’s first full-scale supermarket. We then meet Mr. Tbeleh, who runs a soap factory outside Nablus, inheriting a family tradition of several hundred years duration.

Unlike the often impersonal polemics produced by Boycott, Disinvestment and Sanctions (BDS) advocates, these narratives do not depict helpless victims. The Palestinians whose stories are brought to life here are people with personal agency and distinctive voices. Although the book includes some of the pure polemics we see from the BDS movement, it is these individual portraits that are most memorable and will have the most effect.

With perhaps only one exception — Palestinian journalist and author Fida Jiryis’s first-person essay ‘Occupation’s Untold Story’ — the book is not anti-Zionist. Jiryis offers a fierce condemnation of Israel’s treatment of its Arab citizens, claiming that their opportunities are ‘only the façade of a system of rampant, structural, and institutionalised discrimination’ (339). ‘I am tolerated,’ she writes, ‘at best, allowed to live here because, well, Israel hasn’t figured out a way to get rid of me yet’ (340). Jiryis claims her absolute alienation and intense hostility are universal, but no one who has met many Israeli Arab professionals is likely to agree. ‘The occupation,’ she concludes, ‘is only an extension of Israel’s founding principles, its violent beginnings’ (350) when ‘the Zionist Project decided to expropriate’ (348) the land. Jiryis gives no hope the Jewish state can be reformed; justice would seem to require its elimination.

That actually points to a broader issue with the book. This is a book designed to convince people that the occupation is unjust and intolerable, but it gives no practical suggestions about what can be done to change matters. It is not until the penultimate essay, Colum McCann’s ‘Two Stories, So Many Stories,’ that we get a hint about a starting point for making a difference. That chapter opens with Rami Elhanan’s story, offered in this case within quotation marks as a first-person account. Elhanan is a seventh-generation Israeli Jew whose daughter Smadar was killed by a suicide bomber in 1997. Years later he meets a Palestinian, Bassam Aramin, whose story is also presented as a first-person account. After joining a demonstration at age 12, Aramin sees an Arab boy shot who dies before his eyes. Driven by a need for revenge, he hurls an unexploded hand grenade at an Israeli jeep. It fails to explode, but a prison sentence follows anyway. Both men undergo a conversion to nonviolence and help create the group Combatants for Peace, itself the subject of the compelling 2016 documentary film Disturbing the Peace.

Even that, of course, is not a policy recommendation, but it does demonstrate the outreach, communication, and understanding that can be grounded in empathy. As Canadian novelist Madeleine Thien writes here, ‘Something as innocuous as friendship . . . goes against the totality of the barriers, the checkpoints, outposts,’ and the whole occupation bureaucracy (69). The book’s valuable contribution is the empathy its portraits of Palestinians create and the intimacy readers feel as a result, a kind of readerly version of friendship.

It is not really until the McCann chapter that we get a portrait of an Israeli Jew, but one can accept that that is not the book’s central purpose. The risk with a project that generates empathy for Palestinians alone, however, without providing productive outlets for the anger and sense of injustice that accompanies that empathy, is that it will recruit people for basic opposition to the existence of the Jewish state rather than promote its reform.

That problem carries through into some of the book’s recurrent motifs. Many of the contributors clearly went on one of the group tours of Hebron that Breaking the Silence organises. I went on a private Breaking the Silence trip to Hebron in 2014, and I think no satisfactory understanding of the occupation is possible without doing so. Hebron is without doubt the occupation at its worst: five fragmented Jewish settlements totalling 850 people located at the heart of a Palestinian city of 200,000. Keeping the settlers safe, indeed keeping them alive, requires the presence of several hundred IDF soldiers. The Palestinians nearby are brutalised, their historic markets shuttered, their children subject to arbitrary limits on movement, and the Jews lead bleak lives of continuing anxiety as well. The dynamic is dehumanising for all parties. It disavows the very ‘possibility of commonality and coexistence’ (70), though, oddly enough, political protest that takes the form of an anti-normalisation programme will have the same effect.

Many of the contributors record their experiences of Hebron, including the notorious hostility of some of the settlers, so the book keeps circling back to the same terrain. Breaking the Silence argues that Hebron is paradigmatic, that it embodies the essence of the occupation, and in some ways it does, in that everything is arranged for the convenience of the settlers. Their security is the overriding priority, but so too, as Palestinian author Ala Hlehel writes, is a commitment to ‘guarantee freedom of movement for the new Jewish residents’ in the settlements (24). But Hebron is also unique. The large settlement blocks near the Green Line are home to 75 per cent of the settlers and are laid out precisely to avoid the friction between Jews and Arabs that Hebron makes fundamental. Contrary to what German novelist Eva Menasse writes here, it is in the settlement blocs, rather than in Hebron, that ‘people aren’t even exactly aware that they’re living in a settlement’ (311). At best Hebron typifies to some degree the more isolated Jewish settlements and outposts, not the overwhelming majority of West Bank communities. As I have argued previously in Fathom a debate about whether the Hebron settlements should be abandoned now is well merited, despite the religious investment in Hebron that its history occasions.

As one would expect, several of the essays also make much of the security barrier, 90 per cent of which is a fence, not a wall. Those references build to novelist Helon Habila’s essay ‘The Separation Wall’. As architect Alon Cohen-Lifshitz tells him, ‘Walls can never solve the Israeli-Palestinian problem’ (305). That is perfectly true, but without the barrier terrorist violence would escalate, and it would be even more difficult to resume peace negotiations. ‘Tear down that wall’ would not be a helpful slogan to promote in Palestine.

The long lines that people waiting to cross from the West Bank into Israel proper must endure are frustrating, humiliating, and abusive, but that is a solvable problem. Palestinians themselves asked for the collection of biometric data years ago so that they could pass through checkpoints without physical contact with Israeli soldiers. The software is now in place to facilitate rapid movement of approved workers or travellers through the barrier. A group of more than 250 retired IDF generals has urged increased biometric data collection and the creation of rapid transit lanes so that Palestinians could pass through in seconds, rather than waiting for hours. Thousands more Palestinians should be qualified that way. Where the barrier unnecessarily divides Palestinian land, it should be rerouted. Nowhere does the book offer these practical solutions, instead opting for repeated protests about the wall. Meanwhile, the idea that the two-state solution could work without a physical barrier to block potential aggressors from both peoples is no better than a fantasy.

The book promotes potential confusion about the long lines at checkpoints by blurring the distinction between checkpoints internal to the West Bank and those incorporated into the security barrier. The cumulative result is to marshal political opinion that is less well informed than it ought to be. There isn’t anything fundamentally arbitrary about the existence of a security barrier and the need to monitor passage through what amounts to a prototype international border. The unpredictable and often inexplicable temporary checkpoints internal to the West Bank are another matter, though of course they are not so much of a constant burden to those who live and work exclusively within Palestinian cities in Area A (under full Palestinian control). Both kinds of checkpoints, however, could operate far more smoothly with expanded use of biometric data. Even temporary checkpoints could be accompanied by mobile vans incorporating computerised data. And many internal West Bank checkpoints could be eliminated if Israel transferred some of the narrow corridors of Area C (under full Israeli control) to Palestinian control and thereby fused some of the fragmentary sections of Area A into contiguous Palestinian territory. Even transferring an additional 1 per cent from Area C to A could significantly reduce Palestinian frustration.

The essays that rail, specifically, about the checkpoints in the security barrier often indulge in humanistic protest rhetoric that simply sets aside the history of armed assaults, suicide bombings, and kidnappings that made the barrier necessary. So Jacqueline Woodson, an American author of numerous children’s books, tells us:

The checkpoint reminds me of Comstock, Coxsackie, Elmira — the many prisons I saw as a child visiting my incarcerated uncle. In the heat of the early morning, I watch the people move slowly through, their heads bowed, their IDs held out hopefully — and I wonder what crime brought them to this moment. And I know it is simply the crime of the accident of their birth. And the crime of a nation, of many nations, refusing to see people . . . as people (16).

Once again, the book’s polemical passages can do a disservice to the search for peace. But there are other sections that offer us insights that are surprising and unforgettable. A notable example is writer, editor, and publisher Dave Eggers’s essay ‘Prison Visit’. The prison in question is the open air one named Gaza, which Eggers managed to visit in March 2016. One of the surprises we can share with him is the view of Gaza’s coastline, now a ‘scene of idyllic normalcy in a region known globally only for its conflict, poverty deprivation, and isolation’ (120). Of course that coast was not idyllic during 2014’s Operation Protective Edge, but it is important to know that Gazans could reassert their rights to leisure once the war ended, even if there are limits to the freedom one has on the beach: ‘The conservative version of Islam favoured by Hamas forbids women from wearing bathing suits, and frowns on men swimming shirtless, too.’ (130)

We think of Gaza only as a site of misery, but here and elsewhere in the book we have portraits of individual people living their daily lives despite ongoing challenges. Even the challenges themselves are not precisely as the international press and Israel’s detractors describe them. A Palestinian leader of the seaside wharf tells Eggers his boats have been ‘shot at and seized. His crew has been arrested, handcuffed, detained, and questioned at sea. Worse than the IDF, though, he says are the Egyptians . . . The Israelis will shoot in the directions of their boats, but “The Egyptians will shoot at us directly”’ (132).

Egyptian and Israeli restrictions on travel from Gaza seriously limit the career options of those who want to leave. But meanwhile the day-to-day cultural repression, as Eggers demonstrates in detail, is ‘oppressive and random’ and comes from Hamas. ‘If Gaza is a prison,’ he concludes, ‘it’s a prison with three jailors: Israel, Egypt, and Hamas,’ (129) a perspective the international left has been entirely unwilling to acknowledge. The account of a band that struggles to arrange concerts under the gaze of Hamas is touching and is but one of the stories Eggers recounts that wins our admiration and affection for Palestinians who have otherwise been left faceless victims. The essay’s last sentence drives home the reality of the harmless forms of resistance that put Gazans in danger from the resident jailor: ‘Names have been changed to protect the speakers.’ (156)

For many readers, novelist and photographer Taiye Selasi’s very thoughtful ‘Love in the Time of Qalandiya’ will be equally unexpected. Yet the question she explores — whether Arabs and Jews can date one another and establish romantic relationships that might help overcome the antagonism that structures their peoples’ political relations — has hovered in the margins of Israeli-Palestinian culture for more than a century. Selasi samples high end night life at Ramallah clubs to see if the Palestinian women there who rebel against gender norms will break the prohibition against relationships with Jews. ‘At this table full of rule-breaking women,’ she reports at one nightclub, ‘one rule stands: Arabs don’t date Jews’ (215).

Privately, however, some women admit to past relationships, but the hostility from both Israeli and Palestinian culture mandates secrecy lest the couples face violence. Then there are the nagging existential questions: ‘Is the white man acting out a fetish of the brown female body, a perverse conflation of social privilege and sexual dominance? Does the brown woman betray her anti-oppression politics by “submitting” her body to a member of the oppressing class?’ (216) A ‘racialised imbalance of power’ inherent in the occupation and its ‘countless forms of intimidation’ infects relationships that would establish themselves on other terms. Any yet no more decisive barrier between the two peoples exists than an instilled conviction ‘that to love, that most human of acts, is in fact to betray’ (220).

The reductive, formulaic character of much current debate about the Israeli-Palestinian makes reflection on what Selasi engages in almost unknown. In breaking the taboo against offering anything other than attacks on or defences of Israel with essays like those of Eggers and Selasi, the book makes yet another important contribution to our understanding of the conflict. One can add to those such informative contributions as Israeli novelist Assaf Gavron’s ‘Playing for Palestine,’ which details the role Palestinian soccer teams have in ‘legitimising marginalised groups and fuelling revolutionary impulses,’ (198) projecting national pride and national identity.

Selasi’s essay is among those in the book that expose yet another governing myth about Palestinians, that they all live in abject poverty. Anyone who spends time in Ramallah will meet Palestinians who are quite well off financially and thus not unqualified victims. Wealthy Palestinians are a minority; indeed in Ramallah there is a ‘massive chasm between its upper-class residents and occupied Palestine’s poor,’ (215) but the presence of ‘occupied Palestine’s moneyed class’ necessitates a more nuanced understanding of West Bank culture than the one that prevails among the international left.

All this contributes to the book’s more nuanced portrait of daily life in the West Bank and Gaza. That portrait is enhanced not only by the people we meet, but also by a wealth of local factual detail. Thus, for example, as Dave Eggers writes, ‘Driving in Gaza is not easy — the intersections have no lights, no stop signs, no signs at all, so at every intersection it’s a matter of bluffing your way through.’ (145)

But the book’s pervasive condemnation of the occupation hangs over all. As Hlehel puts it, ‘The occupation is a machine: a complex, octopus-like regime that functions to exhaust those who are subject to it.’ Perhaps most fundamentally of all, it ‘deprives you of your humanity by depriving you of the ability to control time’ (19). The arbitrary imposition of temporary checkpoints within the West Bank layers daily life with incomprehensible frustrations. Chabon suggests ‘pointlessness was the point’ (52). As Hlehel concludes, ‘The occupation bloats time. The occupation is the death of meaning.’ (27)

In his contribution to the book, South America novelist and Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa opens by recalling his history of defending Israel, ‘affirming that it was a pluralistic and democratic society, the only state in the Middle East where there was freedom of expression, freedom for political parties, and truly free elections’ (179). He remains opposed to academic boycotts: ‘It is absurd to penalise universities in Israel for the excesses of their government.’ (180) But he condemns the occupation and those ‘who are convinced that by perpetrating this injustice, they are carrying out a divine plan and will earn their place in Paradise’ (185). Given his history he feels justified in claiming that ‘to denounce and criticise these policies is therefore not just a moral duty; it is also, in my case, at the same time, an act of love’ (186).

Those who cannot tolerate talk about an ‘occupation’ will no doubt not see it that way. But Kingdom of Olives and Ash is a wakeup call to them nonetheless. The challenge now is to move beyond condemnation, to end the occupation, eliminate its corrosive impact on Israeli society, and restore the fundamentals of Israeli democracy.

To this:

“The checkpoint reminds me of Comstock, Coxsackie, Elmira — the many prisons I saw as a child”.

Except that the Arabs have free choice to enter and leave and that their crimes against Jews before there was an “occupation” would have put them in real prisons, not imagined ones.

And that if there is no acceptance of Jewish national identity by those Arabs, even if Israel withdraws, there’ll be no checkpoints at all but a return to pre-67 besieged Israel with no economic interaction.

The San Remo Declaration (1920), The League of Nations Mandate for ‘Palestine’ (1922) and chapter 80 of the United Nations Charter are but three pieces of international law that give the lie to the designation “occupation.”

International law recognises the sovereign national political rights of the Jewish People in The Land of Israel between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River.

Those who challenge that do so not on the basis of law, but out of political or ideological expediency and /or ignorance.

Now, the People and Government of Israel might one day choose to yield some of those rights for the sake of genuine peace ( a very distant prospect, given the intractable hostility of the enemy), but justice, history, law and equity are on the side of the Jews in this matter.