In the first half of the 20th century, most Jews failed to find their way to a successful strategy for dealing with the threat of antisemitism. Some individuals emigrated, for example to Britain, the United States or Palestine. Some found their way into wider civil society, benefited from emancipation, and lived as citizens of European states. Some Jews found communal ways of continuing to live apart, in a changing world.

There were three overlapping political responses to antisemitism. Universalist socialists hoped that revolution would unite workers into a new world where nations, religions and ethnic differences would cease to be important. Bundists wanted to forge a new Jewish identity and institutions through which Jews could exist in peace alongside others and by which they could defend themselves against antisemitism. Zionists believed that Jewish national self-determination was required to ensure the endurance of Jewish life and to create a Jewish capacity for military

self-defence.

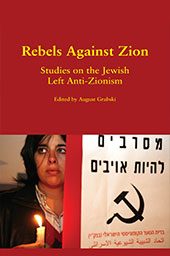

A number of essays in Rebels Against Zion outline the arguments between Bolsheviks, Bundists and Zionists. Roni Gechtman looks at debates within the Second International and the Bund before the First World War and Rick Kuhn focuses on the debates within the Galician Socialist Movement. Henry Srebrnik outlines early Soviet campaigns against Zionism and takes the story into the Stalinist era, with the characterisation of Zionism as ‘pro-imperialist’. Bat-Ami Zucker examines the difficult position of Jewish Communists in America, trapped between their loyalty to the increasingly totalitarian Communist Party, their disdain for the American Jewish establishment and the developing danger Nazism posed to Jews in Europe. Jack Jacobs’s discussion of Bundist opposition to Zionism in inter-war Poland finishes with a crucial, if under-explored observation: ‘The arguments made by the Bund between 1918 and 1939 were not wholly transferable either to the period of the Holocaust or, for that matter, the decades following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.’

The truth, which is not confronted in this book, is that all the strategies adopted against antisemitism failed. Bundism was eradicated in the Nazi gas chambers. Bolshevism failed to stop the Shoah and, while it did succeed in gaining state power over a third of the world, it did not do so by defeating antisemitism but byadopting it in its anti-Zionist variant. Zionism too, as was broadly predicted by both Bundists and socialists, failed to save European Jews in the necessary numbers, and remained, until the 1940s, a utopian movement.

But Israel became a reality, a nation state, not because Zionism ‘won’ the debates outlined in this book, but because the material basis of Jewish life in Europe was utterly transformed by the ‘Final Solution’ and by Israel’s victory in the war of 1948 against the Palestinians and against the Arab Nationalist states which tried to eradicate it at birth.

This brute fact is often ignored, even by Marxists. In a departure from the method of historical materialism, their analyses of Zionism tend to focus more on Zionism as an idea than on the material factors which underlay its transformation from a minority utopian project into a nation state.

In 1954 Isaac Deutscher, Trotsky’s biographer, wrote that he had ‘of course’ abandoned his life-long anti-Zionism. It seemed obvious to him that the world had changed, in Auschwitz and on the battlefield. European Jews had been murdered; the remnants had forged a new nation in Palestine, which Deutscher regarded as a ‘historic necessity’, a ‘raft state.’ Now the key questions changed. It was no longer relevant to ask whether Zionism was a winning strategy against antisemitism; the question was how would the Jewish state reach a peace with its neighbours and how it would negotiate the contradiction between its Jewishness and its democracy?

The political meaning of the term ‘anti-Zionism’ couldn’t be more different after 1948 from its meaning before 1939, yet so often people who consider themselves to be Marxists are more concerned with the continuity of form than with the break in content. Before 1939 anti-Zionism was a position in debates amongst Jewish opponents of antisemitism. After 1948 it became a programme for the destruction of an actually existing nation state.

The conflation of ‘rebels against Zion[ism]’ with rebels against Israel goes unexplored. Often, in fact, the dogged use of the term ‘Zionism’ by anti-Zionists functions to mask the conflation itself and to deny that significant material changes had occurred. One could confront the reality; that history had forged a Hebrew speaking Jewish nation on the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean, or one could deny it. One could come to terms with the world as it existed and start one’s analysis from there, or one could cling onto the hope that the film of history could be unwound, and Israel could somehow be made to disappear. To call Israelis ‘The Zionists’ is to cast them as a political movement rather than as citizens of an existing state; and a political movement can be right or wrong, can be supported or opposed while a nation state can only be recognised as a reality. And if ‘the Zionists’ are characterised as essentially ‘racist’ or ‘apartheid’ or ‘Nazi’, then Israeli Jews can be treated, once again, as exceptional to the human community.

Because ‘Zionism’ is understood in Rebels Against Zion as a phenomenon of European Jewish ideational struggle, Jews from the Middle East are absent from the analysis. But in fact opposition to colonialism and to racism routinely takes a nationalist form, not only in the case of Zionism, but in the case of most anti-colonial movements. Arab Nationalism, and later Islamism, defeated and replaced colonialism throughout the Middle East. While being a strong and often successful way of mobilising against colonialism, nationalism also contains within itself a potentiality for ethnic exclusivity. Jerusalem was by no means the only cosmopolitan city of the Middle East to come under the sovereignty of a nationalist movement. Jews, as well as other minorities, were constructed as second class citizens across the post-colonial Middle East. In Beirut, Alexandria, Cairo, Baghdad, Damascus, Tehran, Tripoli, Algiers, Tunis, and many other places, Jews felt the hostility of the Arab Nationalist movements which took state power, and many left for Israel, or were driven out. In short, in the post-colonial Middle East, ethnic nationalism, with its oppressions and exclusions, was normal rather than exceptional. The tragedy is still playing itself out today in multi-ethnic states such as Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. But the parochialism of Jewish anti-Zionism has little to say about the wider Middle East, except to imagine that Jewish concerns are at the centre of it all.

The editor of Rebels Against Zion August Grabski says something rather interesting at the end of his introduction:

‘Despite the current weakness of Jewish left anti-Zionist organisations, it is precisely the intellectual tradition of those organisations that has dominated the way in which the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is perceived by considerable segments of the international anti-globalisation movement and by organisations and movements to the left of the mainstream social-democratic parties.’

It is understandable that many Jews have a particular interest in Israel. Many of them feel that it is only by chance that they themselves did, or did not, end up there, after the experiences of European, Russian and Middle Eastern antisemitism. Many Jews, following the failure of the international community to guarantee their safety in the 20th century, were won over to the principle of Jewish national self-defence.

Jewish anti-Zionists also tend to have a particular Jewish focus on Israel. They often feel particularly concerned by Israeli human rights abuses, by the injustice of the Israeli occupation and by what they feel is the unthinking support offered by Jewish communal bodies around the world to Israeli governments.

Yet the particular Jewish focus on the crimes of Israel, both real and imagined, is disproportionately influential outside of the confines of the Jewish community. The danger is that this Jewish concern is exported into secular civil society. Thus, for example, a tiny group of anti-Zionist Jews who are for boycotting Israeli academics may have their concerns adopted by an academic trade union. Their particular Jewish concern is understandable, but when a trade union adopts this particular concern with Jewish human rights abuses rather than a consistent concern about human rights abuses in general, then there is obvious potential for the incubation of an unacknowledged antisemitic worldview.

Philip Mendes’s chapter in the volume offers a closely observed and documented case study of such a transformation. He shows in detail the processes and the mechanisms by which a small Jewish anti-Zionist group in Australia played a role in encouraging and licensing antisemitic ways of thinking.

Stan Crooke’s essay is also an outstanding case study of the complex relationship between hostility to Israel and antisemitism. He traces the role of Jewish anti-Zionists as a vanguard, fighting for their own inverse Jewish nationalism in the wider labour movement. And he shows with impressive scholarship how much anti-Zionist ‘commonsense’ was in fact created by the Stalinist and anti-democratic traditions of the Marxist movement.

My worry is that it won’t be the chapters by Crooke and Mendes which will be remembered by most readers of this volume. Rather it will be Jewish anti-Zionism which, through a relentless succession of slippages, omissions and unacknowledged assumptions, will make the lasting impression; beginning with the title, which already bathes those who pick out Israel as a uniquely illegitimate state in the heroic light of minority rebellion.

Comments are closed.