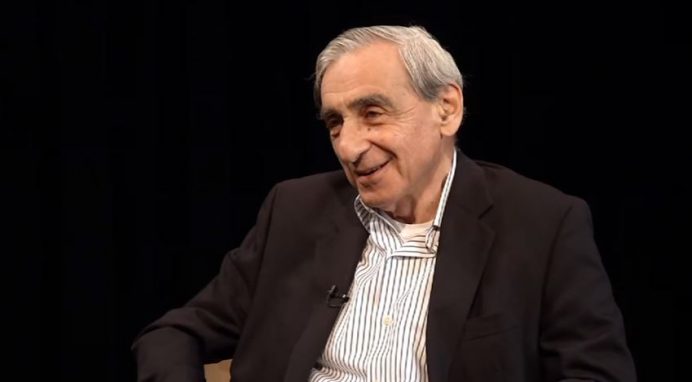

Fathom has invited a series of writers to respond to Chaim Gans’s A Political Theory for the Jewish People (Oxford University Press, 2016). An interview with Gans appeared in our Winter 2016 issue. In April, we will publish an appreciative but critical review by Nahshon Perez of Bar Ilan University. Here, the US political theorist and public intellectual Michael Walzer responds to what Gans writes about diaspora Jews. We invite other responses to the book from our readers.

We should take Chaim Gans’s title very seriously. The book was written, first of all, for Israeli Jews, and it was published first in Hebrew. But it is addressed to ‘the Jewish people’ in Israel and abroad, and this is one of its most striking features. Zionist writers in the past have had something to say to diaspora Jews. Their message was very simple: if you want a Jewish life, you must make aliyah. Pack up and come … now. Gans provides us with a much more extended and nuanced discussion, and it’s that part of his book that I want to consider here.

His discussion begins with the standard view of Zionism’s goal, which he actually shares with his chief adversary, the ‘proprietary Zionists’: the ‘negation of the exile.’ [For Gans’s own definitions of ‘proprietary,’ ‘hierarchical’ and ‘egalitarian’ Zionism see his interview in Fathom.] ‘Negation’ was the goal of pretty much every Zionist writer and activist – even of those who did not think that all Jews would, or should, move to the land of Israel. Negation was a critical stance, directed at the exilic way of life – the ‘way’ as much as the geographic location. In Zionist eyes, exilic Jews were fearful, passive, disorganised, incapable of self-defence, and endlessly superstitious – or they were stooped and scholarly, engrossed in old texts, alienated from nature. Ahad Ha-am’s description draws from these pictures and adds his own perception of the new secular intelligentsia: he was appalled by ‘the lack of unity and order … the lack of [common] sense and social cohesion … the narcissism that holds such terrible sway over the prominent members of the people … the thrill of showing off and the arrogance … the tendency always to be too clever’. Zionism was supposed to make for a more ‘normal’ existence and a healthier culture even in the old country, before aliyah.

So there is a double sense in which the exile is now, in fact, ‘negated’. First, as Gans says, once a Jewish state exists and every Jew in the world can go there, the exile is over – even if, unexpectedly, the diaspora isn’t. But the exile has been negated in another sense, not only by the creation of Israel but also by democratic citizenship in countries like the US. The old stereotypes of the exilic Jew no longer describe us; the mentality of exile is a thing of the past. I don’t mean that we are done with narcissism and arrogance, but we have no more than our share of those two, and all the other pathologies of exile now make only normal appearances among us. We are much more like everyone else, which was one of the goals of Zionism.

Of course, most Zionists believed that a true or authentic normality could only be achieved collectively. ‘Assimilation’ was their name for the individual pursuit of normality. Gans’s egalitarian Zionism would allow the individual pursuit, partly because his is a liberal doctrine in which the idea of autonomy plays a central part, but also because Zionists like Gans recognise that individual pursuit doesn’t necessarily lead to assimilation. There actually is, and therefore there can be, Jewish life in the post-exilic diaspora.

Gans rejects the propriety Zionist argument that this life is inauthentic and unsustainable. He is prepared to accept, perhaps even to celebrate, diaspora Jewishness. But his argument is based almost entirely on the value of individual autonomy. Now Jewish communities in the diaspora are indeed voluntary associations, but that’s not all they are. I did not choose to be an American Jew; I don’t remember ever being asked, when I was 12 and studying my Torah portion, if I actually wanted to become a bar mitzvah – a son of the commandments. Like most Jews, I inherited my Jewishness; I was born into a moral world defined by (some of) the commandments. Yes, I can walk away from that world, but I have a strong sense, which isn’t the product of post-modern ‘self-fashioning,’ that I shouldn’t do that. And I am very critical of Jews who walk away: what right do I have to be critical?

Before I try to answer that question, I need to look back in Gans’s book to the discussion of ‘hierarchical Zionism,’ a doctrine that doesn’t figure at all in the chapter on world Jewry. Hierarchical Zionists hold that in a Jewish state, Jewish symbols, holidays, memories, and histories can be represented in public space, can shape the state calendar, and can determine (but not alone) the curriculum of state schools. This hierarchy of Jewish and non-Jewish cultures can take stronger and weaker forms: if I lived in Israel I think that I would be a weak hierarchalist. I would require political equality and an absolute ban on discrimination in the economy, and I would allow plenty of room for the cultural autonomy of minority groups, but I would also allow the Jewish majority to express its culture in a variety of public places – in much the same way that the Norwegians, the French, and the Bulgarians do in their own nation-states. I would count that as an example of normality.

This kind of normality obviously isn’t possible in the diaspora. But I think that the ‘hierarchical’ version of Jewish peoplehood does have some connection with a certain view of Jewish quasi-peoplehood in countries like the US. It is reflected in the idea that those of us who are engaged members of the Jewish community or who are the community’s civil servants (for diaspora Jewry does have a civil service) have some claim on all other Jews. We ask for their engagement; we expect their support, especially when times get tough. We have no claim on public space in our host countries, but we have a moral claim on the hearts and minds of our fellow Jews.

Everywhere in the diaspora, we are subject to the (weak) hierarchical rights of majority groups, and we mostly accept that (though some of us resent, probably wrongly, the crèche in the public square or the recognition of Christmas as a state holiday). We ask only for full equality and the space to organise whatever autonomous life we can manage. Within this autonomy, however, there is a hierarchy of engaged and disengaged Jews, and the engaged Jews rightfully shape our common life and exhort, criticise, and worry about the disengaged Jews. We recognise, but we haven’t made our peace with, the right to walk away.

I don’t think that Gans gets this quite right, though his willingness to think seriously and generously about us, about the Jews outside, is an important and commendable contribution to the internal conversation of world Jewry.

Comments are closed.