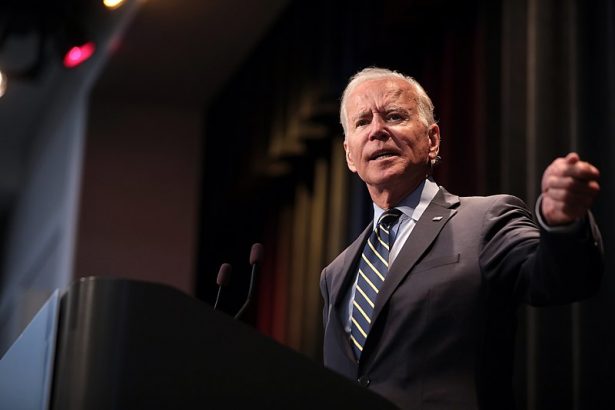

Yossi Kuperwasser argues that President Biden’s Middle East policy reflects the tension between his understanding that the region has gone through dramatic changes during the Trump years that give the US formidable leverage to promote its interests by the use of hard and soft power, on the one hand, and his commitment to a worldview that prefers engagement and dialogue, multilateral action and the demand for human rights adherence from US allies on the other. Should he negate Trump’s legacy and return to the Obama-Biden play book, basing his policy on Iran and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict on a set of false assumptions, he will probably create disagreement with Israel who will remain careful to protect the country’s vital interests. The commitment of both to continue open strategic dialogue and close security cooperation will soften the inevitable tensions.

How to understand Biden’s Middle East policy

The best way to understand President Biden’s Middle East policy is to read carefully what he and his key foreign policy advisers said during the campaign. So far, what they have done since they assumed office is exactly what they said they would do when running for the presidency. It seems that the Biden team has well-established views on the Middle East in general and on the many pre-known hotspots that require its attention, though when new and unwanted challenges emerge the administration is struggling to develop coherent answers, probably out of inadequate preparation and staff work.

In general, the tendency of President Biden, much like his predecessors, is to pivot away from the Middle East, minimise direct investment in leadership attention, military involvement and funding, and instead focus on the long list of more pressing and more important issues for the United States, such as recovering from Covid-19, the sour relations with China and Russia, climate change etc. When it comes to the Middle East, Biden follows the general principles of his worldview and some overarching rules and tries to keep everybody in his base of support happy.

His worldview gives much greater preference to using diplomacy, multilateral cooperation with allies and negotiations with adversaries as tools of persuasion and to promote US interests, rather than the use of power. He gives more weight to human rights considerations, especially when it comes to the countries that belong to the pragmatic camp in the region, such as Saudi Arabia, but which he – like President Obama before him – feel some unease with.

He is committed to erasing whatever he can from Trump’s legacy, and from the political point of view he has nominated to several key positions in his Middle East and foreign policy team people with quite a radical background. He aims to make the centre-left and even the Left wing of the Democratic party feel that they are a part of the decision making process on those issues that are important to them, though the final decisions are made by people with a more centrist worldview like Biden himself and Secretary of State Blinken.

Biden doesn’t seem to have the same passion and left-leaning inclinations of Obama. Nor is it possible for him and his team to completely ignore the substantial changes that took place in the region during the last four years. So, despite the administration’s tendency to distance itself from anything Trump did, it realises that recognition of Jerusalem as the capital city of Israel and support for the Abraham Accords (what the State Department calls the normalisation agreements) will not change. Even the sanctions against Iran are still in place though they are now used for a different purpose.

Some policies have changed. Biden has reassessed the arms deals with the UAE and revoked the designation of the Houthis as a terror organisation, and Trump’s vision for peace and prosperity for Israel and the Palestinians. He has also resumed aid to the Palestinians. Many other policies are still under review and may well change in the coming months. The tempting option of building on Trump’s achievements in the region as a tool to shape a better Middle East was most probably not adopted.

The aggregate outcome of implementing these principles is a policy that is more palatable to the ‘realistic-radical’ in the region, i.e. what remains of the Muslim Brotherhood camp on the Sunni side and the Rouhani camp in Iran on the Shiite side. The administration believes that it can and should help the realistic-radicals in their dispute with the ultra-radicals led by the IRGC and Supreme Leader Khamenei. To some extent it is the same wishful thinking that characterised the attitude of the Obama team, though it is a bit more nuanced approach, and the pro-Rouhani camp element is more subdued as his term nears its end in June.

Iran and the Nuclear Deal

The most pressing issue in the Middle East is Iran. Throughout the campaign, Biden and his team kept saying that they wished to rejoin the nuclear deal of 2015, (the JCPOA) but only after they are assured Iran has completely reversed all its violations of the deal. At that point they would hope to discuss some changes in the deal with Iran so that it will also include ballistic missiles development and Iran’s regional behavior. These discussions, the administration emphasised, would be conducted with the participation of US regional allies. The administration admits that it is willing to discuss the sequence of returning to the JCPOA, and it has managed to open indirect channels of communication with Tehran through Europe. All of this reflects how eager Biden is to return to the deal, which harms his chance of forcing Iran to be the first to return to fulfilling its commitments and to be ready later on to consider changes in the deal.

Faced with emerging challenges that require an American response the administration has remained quite mute, albeit with some exceptions. It conducted a limited attack against an Iranian-controlled Iraqi militia base in Syria after pro-Iranian militias attacked an American base in Iraq. It did nothing after the IAEA briefed its board members that it found anthropogenic uranium particles in two undeclared sites in Iran, or after Iran attacked the Ras Tanura oil terminal in Saudi Arabia and Israeli ships in the Arab Sea, or after Iran started enriching uranium with the advanced IR-6 and IR-4 centrifuges and production of uranium metal. Biden also did nothing about the Iranian decision to limit the access of the IAEA inspectors to important material for three months, or about the Iranian threat that, if by that time, the US sanctions were not lifted, the inspectors’ access would be denied entirely, thus leaving them unable to see the records of what happened during the three months suspension.

The administration’s attitude towards Iran is based on false assumptions and is both counterproductive and self-defeating. The false assumptions are that the JCPOA was a good deal with some flaws that can be fixed through bona fide negotiations with Iran; that Iran can be convinced to adopt a different attitude towards its opponents in the region; that the US can promote a more pragmatic camp inside the Iranian regime; that the ‘Maximum Pressure’ policy failed; and that the progress Iran has made in its nuclear program by violating its JCPOA commitments may enable it to have the capability to produce its first nuclear weapon within a short period of time. Based on these assumptions the Biden administration policy is to reenter the JCPOA and keep kicking the Iranian nuclear can down the road until after its term.

The reality of course is quite the opposite. The ‘Maximum Pressure’ policy caused the Iranian economy and regime enormous difficulties and provides Biden with a golden opportunity to force Iran to accept a much better deal than the JCPOA, if he keeps the policy in place as leverage. It would be possible to craft a new agreement that will deal with the huge deficiencies of the JCPOA, rather than simply bring Iran back to 2015 deal, which is exactly where Iran wants to be, since the agreement paves the way for Iran to have the capability to produce a big arsenal of nuclear weapons after the limits on its nuclear activities are lifted in 2030.

In the current situation Iran is shortening the time it needs to acquire enough fissile material for its first bomb (this time frame is known as the threshold). As Iran cannot eliminate this threshold it remains vulnerable to economic sanctions and to military action if it decides to rush for the bomb. Therefore. Iran is eager to go back to the 2015 deal and rid itself from both the sanctions and from the threshold. The Iranians are conducting a policy of brinkmanship and what they see from the US tells them that their policy is going to work. If an agreement is reached about the sequence of reentering the JCPOA (and Iran can be very flexible to facilitate such agreement) and the sanctions are lifted (thus losing most of the US’ leverage) there is scant chance that Iran can be convinced to adopt a deal that would limit its great benefits from the JCPOA. The last resort option of snapback is the only leverage left and the Iranians may assume that the chance that this administration will use it is very low. This means that if the US is still committed to preventing Iran from having a nuclear weapon its policy is self-defeating.

In fact, the way the indirect talks have begun shows how incompetent this policy is. The Iranians managed to frame the negotiations so that the main question is whether the US should lift all sanctions imposed on Iran since 2016 or only those that are nuclear related, so that nobody speaks of the American aspiration to pave the road to having ‘a longer and stronger’ agreement. If Iran makes any gesture now regarding the sanctions and the sequence of returning to the JCPOA it is going to be seen as flexible and worthy of praise for doing exactly what it wants and the option of a better agreement is going to be lost.

Meanwhile the tension between Iran and Israel keeps rising after the Iranians hit two Israeli ships, American sources leaked that Israel was behind an attack on a ship that was serving the IRGC and one can assume that if the power cut in Natanz was an outcome of hostile activity Israel may have been involved in it. While Iran tries through the attempts to hit Israeli interests to put pressure on the US to rejoin the JCPOA, Israel challenges the US policy and shows that there are better ways to prevent Iran from having the capability to produce nuclear weapons.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Regarding the Palestinian issue too, what Antony Blinken said on behalf of Biden during the campaign is exactly what is happening. This issue receives much less attention from the top decision makers compared with other Middle East matters, such as Iran, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Libya and the Abraham Accords, and it is handled by the State Department and not by the White House, but it is not entirely neglected.

The administration focuses on keeping the two-state solution, which it regards as the only possible solution to the conflict, as a viable option and expects both sides to refrain from unilateral steps that may harm its viability. There is a deep ideological aspect to this attitude. In his conversation with his Israeli counterpart, Blinken emphasised the Administration’s belief that ‘Israelis and Palestinians should enjoy equal measures of freedom, security, prosperity, and democracy’.

The Biden team is trying to improve relations with the Palestinians and to that end it has started adopting a list of gestures towards them without any quid pro quo. The administration is determined to resume aid to the Palestinians (it already announced its intention to donate USD 125 million and declared that it resumes aid to The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) too in spite of its problematic effort to eternalise the conflict and the suffering of its aid recipients and to instill in its schools’ pupils a determination to bring about the demise of Israel as the nation state of Jewish people ) and is looking for ways to bypass the legislation that prevents it from delivering aid to the Palestinian Authority itself because the PA pays handsome salaries to terrorists and their families (the Taylor Force Act). Although it voiced strong opposition to the ICC decision to open an investigation against Israel, it did not take any steps against the PA in this context. On the contrary, it is considering reopening the PLO office in Washington and has already lifted the sanctions that Trump adopted against the ICC chief prosecutor.

However, in the Palestinian case too, Biden will not go all the way back to Obama’s approach. He realises that the situation has changed and some of the changes are irreversible, or indeed should not be reversed. He is not going to retreat from Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital or from the location of the US embassy in the city, but he may reopen the separate consulate to the Palestinians and he has already began making some changes to the language Trump’s team used about disputed issues.

As regarding the Abraham Accords, unlike Trump, whose team initiated the process and was ready to invest considerable American capital in promoting it, Biden shows no enthusiasm about it. He considers it a positive trend but is much more reluctant when it comes to investing in its promotion. This is reflected in the decision to re-examine the sale of the F-35 to the UAE, which naturally sends a chilling message to the potential candidates to join the process. It seems as if the administration is worried that progress in the Abraham Accords process may make it more difficult to preserve the two-state option.

The current administration is not trying to impose dangerous resolutions on Israel, as Obama did with the initiation of UN Security Council resolution 2334. And it is aware of how difficult it is to make progress towards peace, so unlike most previous administrations it is not planning any major initiative in this direction at this point. Instead, it is concentrating on improving the living conditions of the Palestinians and the security of both parties.

But here too, the set of assumptions on which the administration bases its policy is somewhat problematic. It fails to understand what most Israelis have already understood, which is that the major obstacle on the way to a settlement is the Palestinian narrative that negates the existence of a Jewish people and any sovereign Jewish history in the Land of Israel, justifies all forms of struggle against Zionism, rejects any acceptance of Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people and tries to inculcate this perception in the minds of the Palestinian population through incitement and in the international public opinion through the campaign to delegitimise Israel. The recent trend of normalisation between Israel and Arab states could have prompted some soul searching among the Palestinians. The new policy, and the resumption of American assistance without any change in the Palestinian behaviour, may diminish the Palestinian willingness to move in this direction.

Worse than that is the positive international and American attitude towards the Palestinian elections, which indirectly treats Hamas as a legitimate player. Promoting Palestinian unity without clarifying that terror organisations are unacceptable in the political process is a dangerous mistake.

And finally in this context, the administration still believes that if a two-state solution, more or less in line with the Palestinian demands, is not found soon, Israel is bound to lose its ability to be Jewish and democratic state. Therefore, the US must guide Israel to heeding to these demands to help it avoid this inevitable need to choose between being Jewish and being democratic. In fact, there is no such threat, and the status quo can be sustained until the time for a good agreement is ripe (click here for further analysis of this point).

Saudi Arabia and other issues

On Saudi Arabia too, the administration has performed in line with its campaign announcements. Publishing the intelligence report about the Khashoggi murder without directly implicating the crown prince and withdrawing the military assistance related to the offensive activities in Yemen and later pulling out military assets from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf region are all clear messages that under Biden the administration commitment to the kingdom’s security is eroding.

Looked at from a different angle, the Middle East can be seen as a sideshow within the greater US conflict with China and Russia. This is relevant in many countries in the region that are a target of China’s ambitious Belt and Road plan or subject to Russian military, diplomatic and economic overtures. The US under Biden is not tempted to turn the region into a major superpower confrontation arena and prefers to ignore the challenge except for Israel where it is keen to keep China away from strategically sensitive projects.

Syria, Lebanon and Iraq may become important countries, but so far not much attention has been given to them. As yet, American policy has not changed considerably.

Impact on Israel

What does all this mean for Israel’s relation with the US under Biden? The answer to this question depends to some extent on the kind of government Israel will have once it manages to solve the domestic political conundrum. But it is, anyhow, reasonable to expect that the relations will be characterised by close consultations reflecting the strategic nature of the relationship between the two countries, and by ongoing strong security cooperation.

At the same time, there is going to be some bitterness and suspicion as their approaches on many topics differ and are sometimes contradictory. This is already easily visible when it comes to the policy towards Iran and especially the JCPOA and with Israeli concerns about American steps and language when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It’s clear that any Israeli government would like to avoid an open confrontation with the Biden administration. So far, its deeds do not justify an open rift. But Israel would have to make sure that its vital interests are not compromised. To that end it will have to use the strategic dialogue with the US to discuss the false assumptions upon which the Biden administration bases some of its key policies. If and when, Israel may find it necessary to take action to prevent developments that may endanger its security it is probably going to do so..

Finally, a side effect of the US preference for the realistic radicals over the pragmatists in the region may be the strengthening of the relations between Israel and the pragmatic camp, as Israel is considered a force, or maybe the only force, that can be relied upon and does not change its policy that often.