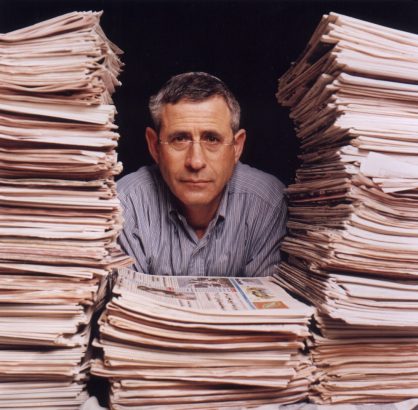

Dr Mordechai Kedar spoke to a Fathom Forum in London in September 2014 about why so many Western commentators get Middle Eastern politics so wrong.

We do not understand the importance of non-state, non-national loyalties

People tend to think of the Middle East as being composed of ‘states’ just like Britain, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. This is a big mistake. Arab nationalism as an ideology never really succeeded in replacing the traditional loyalties which exist in the Middle East: tribe, ethnic group, religious group and sectarian identity.

Most Middle Eastern states are controlled by minorities which are totally illegitimate. Take the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. These people are not Jordanians: they were from Saudi Arabia (then the Hejaz) and the British gave them the emirate of Transjordan, which later became the Kingdom of Jordan. But who, when they write about Jordan, takes into account that it is viewed by at least the Palestinians of Jordan (the majority) as an illegitimate regime? Similarly, Gaddafi was not a representative of the nation of Libya (if there even is such a nation). He represented his small, very vicious tribe. ‘Gaddafi’ is the adjective of the tribe’s name – Qadhadhfa – which means ‘the one who sheds blood [of others].’ (You know, Turkey’s former president Suleyman Demirel said that the Middle East is like a very big feast. Everybody takes part and if you are not in a chair, you are on the plate; it is your decision. I think that recently, the Middle East is much easier to understand in terms of this big feast.)

We don’t understand how weak these ‘states’ really are

After the First World War loyalty to the ‘state’ was supposed to replace the traditional loyalties of tribe, ethnic group, religious group and sectarian identity. People living in Iraq, for example, were no longer to identify as members of the 75 tribes but as Iraqis. But it didn’t work. What we see in Iraq today demonstrates the failure of this ‘Iraqi state’ to become the focus of identity or to replace other loyalties: people remain loyal to their tribe and to their traditional ethnic and sectarian identities. The same thing is true in Syria, in Libya, in Yemen – most of these countries failed in their ‘nationalism.’ Do not forget that the borders of these countries were not defined by the local people; they were defined by colonialists to serve Western interests and so those borders are often not viewed as a legitimate political framework. So when we talk about ‘Arab states’, we must take into account that these states are totally different to those of Europe, in terms of the basic legitimacy of the state in the eyes of those who live there.

In Iraq, the army would not fight ISIS to defend the Iraqi state. Syrian Soldiers in Syria defected in big numbers during 2011-12, with only those loyal to Assad’s Alawite sect remaining loyal to ‘the state.’ That’s why they needed Hezbollah to come and fight for them, because half the army ran away. This happened in the Libyan army too. At the beginning of the civil war it split into two parts, one part fighting with Gaddafi, the other against him. At least half of the army viewed him as illegitimate. All these ‘presidents’ appear to be powerful, but when you drill down you see that they are very weak because they rely on the dictatorship and repression to maintain their power.

Tragically, all this is much easier to explain today because of the catastrophe in Syria.

We are too trusting of official sources

Often people in the West don’t do the proper research. If you do not go on the streets, conduct surveys and speak to people, you don’t know if what you are reading is accurate. And in some states, such as Syria, you were never allowed to do real research. If you relied on newspapers you were told that Syrians were all nationalists and loved Assad. My book, Assad in Search of Legitimacy: Message and Rhetoric in the Syrian Press Under Hafiz and Bashar, showed that it was a façade. Assad was viewed as illegitimate; nobody loved him, everybody hated him. He was especially hated by the Muslims because he is from the Alawite sect and the Alawites are viewed by Muslims as infidels.

We do not understand the Al Jazeera effect

If the Arab world could be compared to a ball of explosives because of the illegitimacy of the states and the regimes, then Al Jazeera surrounded it with gas fumes by its incitement, especially against the regimes. Al Jazeera’s Arabic news channel has had a very clear agenda since it was launched in 1996: a mix of anti-regime, anti-Israel, anti-West, and pro-Muslim Brotherhood messages. Al Jazeera has been the mouthpiece of the Muslim Brotherhood since it began to function.

All it needed was a spark to ignite the whole thing. That spark came from Tunisia in December 2010 when a guy named Mohammed Bouazizi set fire to his clothes because a policewoman slammed into him into the street. He, as a man, couldn’t take the humiliation of being slammed by a woman; he couldn’t do anything against her because she was the authority, so he set fire to his clothes and burned himself to death. His colleagues started demonstrating against the police and demonstrations spread to the capital. After a month Ben Ali, the president, went away and Al Jazeera (which broadcast the scenes from Tunisia 24/7), asked constantly, ‘which will be the next country?’ So one day after Ben-Ali went away it started in Egypt, then a week later it started in Libya, in Yemen and, in March 2011, in Syria. As well as the demand for the dictator to go, all the traditional and repressed loyalties – to tribe, religious group, sectarian group – came out onto the streets, killing and injuring whoever they met.

From ISIS to IS

We were shocked by the sudden rise of IS because we did not understand these things. We did not understand how weak Iraq and Syria were. The collapse of the regime in Iraq started with the invasion in 2003; since then, the system never stabilised. Sure, they had elections, but the resulting institutions, like the Iraqi Parliament, actually represented the tribes, and since the tribes are fighting each other, the elected representatives also fought each other. And the economy in Iraq can’t grow because of the fighting. They are producing only 15 per cent of the oil which they were producing in the days of Saddam. Why? Because of the mayhem. Who would invest in that? These countries could be heaven because of the oil, but they are hell because of the constant fighting between ethnic and tribal groups. So in the end these countries were so fragmented and weak that a few thousand jihadists in pick-up trucks could take a third of Iraq and a third of Syria and create an Islamic State.

It is worth noting the significance of the name, ‘Islamic State’. The Caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi – another seventh century term – omitted ‘Iraq and Syria’ from the name because in his view he is in charge of all the Muslims from Indonesia in the East all the way to California in the West. And he wants to be in charge of the whole world when it converts to Islam, either willingly or by force. This is his world view and we don’t have the luxury not to take him on face value because he says what he means and he means what he says; it’s time to take him very seriously.

Regrettably too many in the West, especially the Left, view discussions about Arab tribalism as ‘whataboutery’ and continue to blame Israel for all its woes.

Trenchant analysis delivered in deceptively innocent spoonfuls. Modechai Kedar’s depth of understanding underscores the superficiality and irrelevance of most “reporting” on the ME.

That’s only half the story. The West is incapable of viewing anything outside the vanity of its own cultural viewpoint. The Israeli Left, a lacky of the West, is exactly the same. They are all invested with the classical liberalist rubbish and racism about human universalism.

These ideological drivers provide for the facade and mockery of Arab ‘negotiation’ that is just interminable warfare against Israel, which the West for either anti-Semitism, incompetence or self-interest refuses to address.