Joel Singer is the former Legal Adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry under the Yitzhak Rabin-Shimon Peres Government. He negotiated the Israel-PLO Mutual Recognition Agreement and the Oslo Accords (1993–96). In this article he tells the story of Rabin’s 1989 Peace Initiative which he helped draft and which, he suggests, shows why congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was wrong to withdraw from this year’s Commemoration of Rabin’s assassination.

When Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently withdrew her participation in a commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin – an event organised by Americans for Peace Now – a heated debate commenced: Was Rabin, the Israeli Prime Minister who agreed to shake the hand of PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat and sign the Oslo Accords (for which he was assassinated) a man of peace, a hawk turned dove, as he has been universally idolised? Or was he, as Ocasio-Cortez and her supporters claim, a hawkish general who ordered the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers to break the bones of the Palestinians during the 1987 Intifada, who opposed the creation of an independent Palestinian state (because Rabin told the Knesset that his vision was to give Palestinians ‘an entity which is less than a state’) and who is incorrectly celebrated as a dove because of his subsequent involvement in Oslo?

In fact, both claims are wrong. As I have already recounted, Rabin intended the Oslo process to lead to a Palestinian entity separate from Israel. While Rabin was careful not to use the words ‘independent state,’ as he struggled to obtain wide Israeli support for the Oslo Agreement, he knew well that he was leading Israel towards that outcome. More broadly, Rabin was neither a hawk suddenly turned into a dove in Oslo, nor a hawk pretending to be a dove. Rather, he was always a hawk on security matters and a dove with regard to policy issues, particularly the fate of the West Bank and Gaza. While signs of Rabin’s dovishness emerged much earlier, nowhere was Rabin’s central role in seeking peace clearer than when he published his own Peace Initiative in 1989.

At the beginning of 1989, in the midst of the Palestinian uprising – known as the first Intifada – Rabin asked me to help him in developing a new peace initiative focused on holding Palestinian elections in the West Bank and Gaza and commencing political negotiations with the elected Palestinian representatives. Rabin then served as Minister of Defense in a Likud-Labor national unity government headed by Likud Party leader Yitzhak Shamir. I was then the Director of the International Law Department in the IDF, in which position I advised the Minister of Defense and the IDF on legal issues associated with the administration of the West Bank and Gaza and on negotiating agreements with Israel’s Arab neighbours. On 14 May 1989, the Israeli Government adopted a peace initiative, which was based on Rabin’s plan.

Four years later, when Rabin, having become Israel’s Prime Minister, shook hands with Arafat, sealing the Oslo Agreement deal on the White House lawn, I again assisted him and his Foreign Minister Shimon Peres in negotiating the Oslo Agreement, this time as Legal Advisor to the Israeli Foreign Ministry.

As someone who worked closely with Rabin on both his 1989 Peace Initiative as well as the Oslo Agreement, I can confirm that Rabin, ever the grand strategist whose legs always stood firmly on the ground, never converted. Nor was his support for the ideas he advanced in his 1989 Peace Initiative and in Oslo non-genuine. He always maintained, and both his 1989 Peace Initiative and his 1993 Oslo initiative reflected, the same dualism of hawkish security and dovish long-term policy thinking.

Unlike Israel’s right-wing leaders whose attitude towards the West Bank and Gaza is based on ideology, Rabin’s approach was pragmatic: He was seeking peace and stability on Israel’s Eastern front. As he considered the options of who should be Israel’s partner in the discussions over resolving the Palestinian problem – a choice of Jordan, local West Bank and Gaza Palestinians, or the PLO – Rabin’s preference was to partner with Jordan which stood to offer the best chance for a stable peace, but as Jordan increasingly separated itself from the West Bank, Rabin was prepared to adjust his tactics to reflect changing circumstances.

The real change in Rabin’s thinking thus actually occurred in his 1989 Peace Initiative, when he substituted his long-standing support for the ‘Jordanian Option’ – that is, the return of the West Bank to Jordan – with a Palestinian-centered approach to determining the future of the West Bank. Rabin’s agreement to talk with the PLO in Oslo in 1993 occurred only after he had recognised that West Bank and Gaza Palestinians were too weak to discuss their future with Israel without the PLO’s leadership. Thus, despite the Israeli public and Rabin’s own distaste for the group – long considered a terrorist organisation in Israel – Rabin assessed in Oslo it was the PLO with whom he must negotiate.

Prelude to Rabin’s 1989 Peace Initiative

When the Palestinian Intifada broke out in December 1987, as Minister of Defense, Rabin took all measures at his disposal to extinguish terror operations and the wide-scale demonstrations disrupting public order. To that end, he used all the governmental security measures available against rioters, including blockades on towns and villages, administrative detentions, house destructions and deportations. Regarding the continuous mass demonstrations, Rabin was quoted as saying, ‘we’ll break their bones.’ Although he denied using this phrase, he admitted that his intentions were to disable terrorists and disrupters of public order by using aggressive but non-lethal measures.

For many years prior to the outbreak of the 1987 Intifada, Rabin’s approach to the resolution of the Israel-Arab dispute on Israel’s eastern front was based on the Jordanian Option. That is, in his view, the fate of the West Bank and the ‘Palestinian Problem’ should be resolved in negotiations with Jordan and include the return of the majority of the West Bank to Jordan, with Israel keeping only Jerusalem and some additional West Bank territory based exclusively on security considerations. Jordan had controlled the territory from 1948 until 1967, when it lost the West Bank to Israel during the Six Day War. Given Jordan’s historical and demographic connections to the West Bank, and Rabin’s strategic-based preference to deal with sovereign states rather than with non-state organizations, his choice seemed a logical path.

On 31 July 1988, however, Jordanian King Hussein declared that Jordan was cutting all legal and administrative ties to the West Bank. This was followed by an August 7th press conference in which Jordan announced it would never again assume the role of speaking on behalf of the Palestinians. To Rabin, these steps all but closed the door on the Jordanian Option. In parallel, after several months of unyielding Palestinian struggle, Rabin became convinced that the uprising was led by grassroots local residents, rather than under instructions of the PLO leadership headquartered in Tunis. Rabin realised that the uprising not only expressed the despair of the Palestinian people at the status quo, but also authentic Palestinian national aspirations.

Throughout the Intifada, Rabin repeatedly declared: ‘They will attain nothing by force, only at the negotiating table.’ But the departure of Jordan from the picture in July 1988 brought into question whether such a table could ever exist, given that Rabin had traditionally rejected any negotiations with the PLO. As Rabin then explained, the PLO’s position called for an independent Palestinian state, Israeli withdrawal from the entire West Bank and East Jerusalem to the pre-1967 borders (known as the ‘Green Lines’), and the return to Israel of millions of 1948 Palestinian refugees. Rabin did not accept any of these demands, which he thought posed mortal dangers to Israel. Therefore, for Rabin, negotiating with the PLO was out of the question.

With the Jordanians and PLO not an option, in July 1988 Rabin began contemplating opening discussions about a political solution with local Palestinian leadership. For Rabin, this idea was the logical extension of his call to the Palestinians to replace rioting with negotiations. He thought that commencing negotiations with local, non-PLO Palestinians would serve two goals. The immediate objective was to enhance the security situation: stopping the violence of the Intifada through political, rather than military means. The long-term objective was to seek to advance toward a peaceful resolution to Israel’s dispute with its neighbours on its eastern front: the Jordanians and the Palestinians.

Rabin’s strategic objective continued to be one state on Israel’s Eastern border: a Jordanian-Palestinian state. But since Jordan then declared it would not talk with Israel about the future of the West Bank and Gaza, Rabin thought that Israel should, as a first step, begin talking directly with representatives of the Palestinian residents of these areas about their future, which Rabin believed should ultimately become associated in some fashion with Jordan.

Rabin’s planning gained urgency towards the end of 1988. Following a speech given by Arafat in Geneva on 14 December 1988, in which Arafat finally accepted, on behalf of the PLO, the three conditions set by the US for talking with the PLO: recognition of Israel’s right to exist, acceptance of UN Security Council Resolution 242, and the renunciation of terrorism. On this basis, on the same day, US Secretary of State George P. Shultz confirmed that the United States would open a dialogue with the PLO.

These developments clearly concerned Rabin – building on the move, the United States might press Israel to also begin discussions with the PLO and may develop an American peace proposal, pushing for terms unfavourable to Israel. To Rabin, better for Israel to shape the direction of peace efforts by making its own proposal, than to be overtaken by events. Thus, at the end of 1988 Rabin decided to develop and publish a peace initiative based on opening direct discussions with representative West Bank and Gaza Palestinians.

This was a fairly remarkable step for the Defence Minister. Before publishing his plan, Rabin neither presented it to, nor consulted with, Prime Minister Shamir. Nor did Rabin first discuss his plan with the leader of his own Labor Party – Shimon Peres, who, as a result of the Israeli elections just days earlier (November 1988), had taken the position of Minister of Finance. Peres thus was removed from the center of hectic diplomatic activity in which he had been intensively involved in the previous four years as Israel’s Prime Minister and later Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Rabin’s Peace Initiative

To officially launch his new peace initiative, Rabin would have been required to first secure a governmental approval of his proposed peace plan, which presented difficulties given the hardline, rightist ideology of the Likud Party forming half of the national unity government (along with Rabin’s Labor Party). The Likud opposed any concessions with regard to the West Bank and Gaza. To overcome this political constraint, Rabin decided to first reveal his peace initiative to the Israeli media. Thus, during a 19 January 1989 press conference with reporters covering the West Bank and Gaza, Rabin laid out his peace plan in a well-prepared speech.

Rabin opened by saying that reaching peace on Israel’s Eastern border requires talking with two partners: Jordan and representatives of the West Bank and Gaza residents. He repeated his long-standing preference for Israel to reach peace agreements with sovereign countries, but acknowledged the difficulties in pursuing this goal in reaching a solution for the West Bank and Gaza, given Jordan’s abandonment of any administrative or legal responsibility in these areas. Thus, a new Palestinian address had to be found to discuss a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Rabin then recounted how, since he had become Minister of Defense in 1984, he had repeatedly asked Palestinian leaders why they would not take the driver’s seat in discussing their future with Israel. The answers he had always received were ‘only the PLO can speak for us’ or, ‘if we dared to speak with you, the PLO would kill us.’ Rabin then noted that, after the outbreak of the Intifada, the tone of the Palestinians with whom he was talking had changed. He felt that they were more confident and that the equation of power between West Bank and Gaza residents and the PLO had changed in their favor, thus making them more prepared to talk with Israel. Palestinians on the ground in the territories had organised a resistance movement of their own, while the PLO leadership only watched from Tunis.

Rabin then proceeded to describe an approach for opening discussions with the Palestinians, emphasising that these were his private views, not the Israeli Government’s. He began by noting that the new Likud-Labor national unity government’s Basic Policy Guidelines of the Government’s Program (Government’s Guidelines), which were adopted on 22 December 1988 – that is, just days before Rabin launched his Peace Initiative – while opposing contacts with the PLO, called for striving to open a dialogue with residents of the territories.

Rabin then proceeded to lay out a three-phase peace initiative to the reporters. The first phase, he explained, would be to allow Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza to select their own representatives in whatever way they would prefer – a step which would be recognised by Israel. If they wanted to do so through elections, Rabin added, he would support it. Any such elections, Rabin added, would be held after a 3-6 month period of calm – that is, cessation of the Intifada violence. These elections would be free, unimpeded by Israel, and Israel would accept those elected as legitimate representatives of the Palestinians. In subsequent interviews and speeches Rabin repeatedly confirmed that Israel would be prepared to talk with any West Bank and Gaza residents elected by the Palestinians regardless of their views. Rabin thus drew a clear line between local, pro-PLO representatives, which he accepted as partners to negotiations, and official members of the Tunis-based PLO, which Rabin did not accept as partners to the negotiations.

In the next phase, Rabin added, the elected Palestinians would enter into negotiations with Israel over creating ‘expanded’ autonomy or self-rule for the Palestinians for an interim period. He emphasised that there would be no pre-conditions set by Israel for the negotiations regarding the interim period, other than that responsibility for security would remain with Israel. All other details of an agreement could be determined later in negotiations between Israel and the elected Palestinian representatives. By using the term ‘expanded,’ here and repeatedly in subsequent interviews, Rabin signaled to the Palestinians that the scope of the Palestinian self-rule he envisioned was much larger than that proposed previously by the Likud-run Government.

As to the fate of the West Bank after the end of the interim period, Rabin added, the Palestinians would decide whether they want to enter into a kind of collaboration with Jordan, such as a federation. In subsequent interviews, Rabin simply talked about an unspecified link between the West Bank, Gaza and Jordan. Rabin noted that he also did not rule out the idea of a federation between the Palestinians and Israel, if that would be their wish.

Rabin saw three distinct phases in implementing his Peace Initiative. First, elections for the Palestinian representatives of West Bank and Gaza residents. Second, negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian representatives to define the terms and conditions of Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza for an agreed interim period. Third, negotiations between Israel, Jordan and the Palestinians regarding the peace arrangements between the three partners. As to the latter phase, Rabin explained that Israel could not accomplish peace on its Eastern front without Jordan, but that it could also not accomplish peace solely with Jordan. Therefore, there is a need for the participation of all three parties in those discussions, in which Jordan and the Palestinians would be two equal partners.

A copy of a draft of Rabin’s Peace Initiative – which I helped develop in early 1989 based on discussions with Rabin – appears in an annex below. Because this draft reflects Rabin’s initial ideas, before they were modified in order to be acceptable to the hardline Likud Party so that the plan could become Israel’s, not just Rabin’s, Peace Initiative, the draft is illustrative of Rabin’s original thinking. In early 1989, at Rabin’s request, I also developed a detailed Palestinian elections plan, which is not reproduced here.

Adoption of Rabin’s Initiative by the Likud-Labor National Unity Government

Following his press conference, Rabin commenced a process of marketing his peace initiative to West Bank and Gaza Palestinians, his Labor Party members, Egypt, the United States and Prime Minister Shamir. Palestinian leaders from both the PLO and the West Bank and Gaza, as well as leaders of the Israeli hardline right, quickly rejected the plan. As expected, Shamir’s reaction was lukewarm. At that time, Shamir too was in the process of developing his own peace initiative that also included Palestinian elections, but in all other respects it was significantly less forthcoming than Rabin’s plan. Rabin, however, was not discouraged and continued his efforts to build support for the plan.

On 14 May 1989, the Israeli Government adopted Rabin’s Peace Initiative after removing some of Rabin’s expressions that seemed too progressive for the Likud Party’s taste, replacing these phrases with more standard Likud Party phraseology. Going further, the Likud introduced two more substantive changes to the plan. First, a call to Jordan and Egypt to join all phases of the peace talks alongside the Palestinians. Second, the elected Palestinians would not only be the Palestinian representatives to the peace talks with Israel, but also would constitute the self-governing authority during the transitional period.

In recognition of Rabin’s authorship of the 1989 Peace Initiative it has often been referred to as the Shamir-Rabin Peace Initiative.

Rabin’s 1989 Peace Initiative and the 1978 Camp David Accords Compared

By and large, Rabin’s plan was based on the 1978 Camp David Accords, which were referenced in the Israeli Government’s Guidelines as the basis for seeking peace on Israel’s Eastern front. While the Accords are mostly remembered today for providing a framework for achieving peace between Egypt and Israel, the accords also included a separate framework for achieving autonomy for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. The Camp David Accords assigned Egypt the role of representing the interests of the Palestinians in the negotiations with Israel, while also calling on Jordan to join the process and asking both Egypt and Jordan to include West Bank and Gaza Palestinians in their delegations to the negotiations.

The Camp David Accords envisioned a three-step process: First, negotiations between Israeli, Egyptian and American delegations on developing an autonomy agreement that would establish a Palestinian self-governing authority to govern the West Bank and Gaza Palestinians for a transitional period of five years. Then, holding elections in the West Bank and Gaza to select the Palestinian representatives that would comprise the self-governing authority. And finally, holding discussions between delegations of Israel, Egypt, Jordan and the Palestinians to determine the permanent status of the West Bank and Gaza.

When Rabin launched his Peace Initiative, the Camp David Accords were already a dead letter. Jordan had refused to join peace talks based on the Camp David Accords and Egypt was not able to find any Palestinians that would agree to join its delegation. For several years after Camp David, Egypt alone held discussions with Israel, with the participation of the United States, on an autonomy agreement for the Palestinians. However, the discussions were suspended in 1983 with no agreement reached. As a result, no Palestinian elections were held, and the Palestinian self-governing authority envisioned in 1978 was never created.

While Rabin supported the Camp David Accords in 1978 as a leader of the Labor Party, then constituting the Knesset’s largest opposition party to Menachem Begin’s Likud-led Government, these accords were never Rabin’s cup of tea. Begin conceived the Palestinian autonomy idea, which became the cornerstone of the Camp David Accords, as a means to perpetuate Israeli control of the West Bank and Gaza. Rabin, conversely, believed that Israel should withdraw from the large majority of the West Bank and Gaza as part of establishing peace with Israel’s Arab neighbours. Yet, in 1989, Rabin decided to anchor his new peace initiative in the Camp David Accords and the Government’s Guidelines, because they were both already agreed upon by the Likud. Rabin thought that this would increase the chances of making his Peace Initiative more acceptable to Shamir and his fellow Likud hardliners with whom Rabin’s Labor Party had just partnered to form the national unity coalition government.

Thus, rather than coming up with a completely new idea, he decided to build upon the Camp David Accords, adjusting its basic concept to the new reality and instilling his own policy preferences into the modified version of the accords.

The four main changes Rabin introduced in the Camp David Accords scheme were as follows:

- Under the Camp David Accords, Egypt would represent Palestinian interests in the first round of negotiations with Israel over an autonomy agreement to create the Palestinian self-governing authority. A Palestinian delegation would participate only in the second round of negotiations over the permanent status agreement, after the Palestinian elections had taken place and the self-governing authority had been created. Rabin’s Peace Initiative called for Palestinian participation in both rounds of negotiations with Israel, and in the first round – alone, thus strengthening the Palestinian role significantly.

- Consistent with the first change, Rabin’s Peace Initiative also reversed the order established in the Camp David Accords between the negotiations over an autonomy agreement (phase one) and the Palestinian elections (phase two). Under Rabin’s Peace Initiative, the Palestinian elections were to be the first phase, making the Palestinian negotiators at the table legitimately elected representatives of West Bank and Gaza Palestinians.

- Two consecutive Likud Prime Ministers – Begin, who negotiated the Camp David Accords, and Shamir, who was the Prime Minister when Rabin launched his Peace Initiative – both refused to recognise the Palestinians as a people. Prior to signing the Camp David Accords, Begin even insisted on receiving a letter from U.S. President Jimmy Carter stating that Carter acknowledges that Begin has informed him that ‘[i]n each paragraph [of the Camp David Accords] the expressions “Palestinians” or “Palestinian people” are being and will be construed and understood by [Begin] as “Palestinian Arabs.”’ Rabin, conversely, referred to the Palestinians in his Peace Initiative and in his public speeches as a people and emphasised that they constitute a distinct people (see section 3 in the draft of Rabin’s Peace Initiative below). In the version of the Peace Initiative adopted by the Israeli Government (requiring Likud buy-in), the reference to the Palestinians as a people was replaced with ‘Palestinian Arabs,’ consistent with the letter obtained by Begin from Carter. Rabin had to compromise on this point with his Likud partners in order for his initiative to be adopted. The Oslo Accords that he negotiated as Prime Minister four years later (1993) referred to the Palestinians as a people.

- Rabin very much appreciated the indispensable role that Egypt could play in facilitating the discussions between Israel and the Palestinians. Yet, he understood that Egypt no longer wished to represent the Palestinian interests in the negotiations over the resolution of the Palestinian problem, as Egypt had done when it had negotiated the Camp David Accords with Israel. In his Peace Initiative, therefore, Rabin did not assign Egypt any formal role in the negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians. When the Israeli Government adopted Rabin’s Peace initiative, an invitation to Egypt to join both phases of negotiations was added. Rabin accepted this addition. In fact, however, Egypt did not formally join the negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians but, instead, played an extremely important role in facilitating such negotiations.

The Aftermath of Rabin’s Peace Initiative

The most important part of Rabin’s Peace Initiative – jumpstarting the peace process by first holding Palestinian elections – managed at once to address two significant hurdles that previously prevented the Camp David Accords formula from leading to real progress. By further empowering West Bank and Gaza Palestinians through the elections, the initiative identified a legitimate substitute for both Jordan (which had decided to disconnect itself from the territories) and the PLO (with which Israel, including Rabin, refused to talk).

However, for Rabin’s plan to be implemented, Palestinians would need to accept it. Rabin considered Egypt to be a key player in accomplishing this objective. On 15 September 1989, Egypt’s President, Hosni Mubarak, endorsed Israel’s Peace Initiative, with some proposed modifications, when he formally published his Ten Point Plan. Mubarak’s three main modifications to the Israeli peace initiative were to propose that Palestinians living in East Jerusalem also participate in the elections; that there would be a freeze on Israeli settlements during the Israeli-Palestinian negotiation period; and that a Palestinian delegation be formed, with Egyptian and American assistance, to negotiate the details of an agreement before the elections.

Because the two parts of the Israeli national unity government couldn’t reach an agreement regarding Mubarak’s proposal (the Likud Party rejected it while the Labor Party, with Rabin’s strong endorsement, supported it), Rabin visited Egypt three days later to begin discussions with Mubarak over his plan. Meanwhile, Egypt held discussions with Palestinians, including PLO representatives, in an attempt to bridge the gap between the Israeli and Palestinian positions regarding how to implement Israel’s Peace Initiative.

On December 6, 1989, U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker III published a Five Point Plan that was intended to help Egypt and Israel to move along in the process. The U.S. role at that time focused on finding a formula that would allow the formation of a Palestinian delegation to talk with Israel prior to the elections. These efforts were intended to accommodate Palestinian requirements by: (1) lessening the PLO’s objection to the process, which excluded formal PLO participation, by including in the Palestinian delegation at least one Palestinian affiliated with the PLO while not being a high-ranking member of the PLO; and (2) including at least one Palestinian resident of East Jerusalem in the Palestinian delegation to facilitate Palestinian acceptance of Israel’s condition that East Jerusalem would not be part of the autonomy arrangements.

Rabin’s diplomacy during this period was delicate and complicated, at once seeking to find, through his contacts with Egypt and the United States, mutually acceptable compromises to address Palestinian requirements, without antagonising the Israeli Government Likud partners to his right. Thus, Rabin actively sought formulas that could accommodate these two Palestinian demands, while also working with Prime Minister Shamir to convince him not to object to Rabin’s own proposals. During this period, Rabin held intensive discussions with the United States, primarily through frequent meetings with the U.S. Ambassador to Israel (often held secretly), ultimately culminating in Rabin’s visit to the United States in January 1990, in which he met with Baker and senior American officials to advance his proposals.

On the linkage between the Palestinian delegation to the PLO, Rabin proposed that Israel would allow at least one resident of the West Bank and Gaza who had been deported by Israel from these areas due to his support of the PLO (and who was presumably affiliated with the PLO while in exile) to return to the territories and then be included in the Palestinian delegation. The PLO thus could view that person as a PLO representative, while Israel could assert that, upon his return to the territories, that person was not a PLO member.

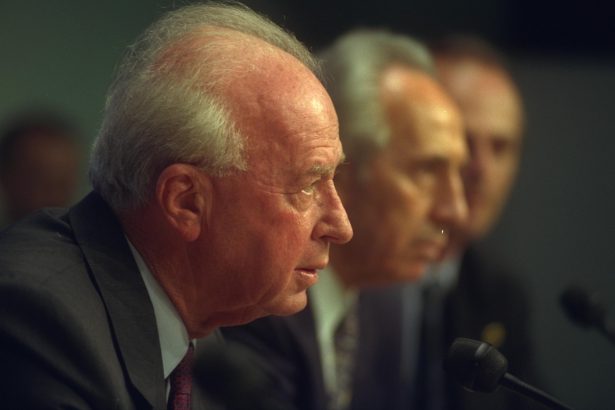

(From left to right: Joel Singer, Israeli Prime Minister Rabin, Egyptian President Mubarak, US President Clinton, Jordanian King Hussein and PLO Chairman Yassar Arafat at the signing inside the White House on 28 September 1995 of the Oslo II [full name: The Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip].)

(From left to right: Joel Singer, Israeli Prime Minister Rabin, Egyptian President Mubarak, US President Clinton, Jordanian King Hussein and PLO Chairman Yassar Arafat at the signing inside the White House on 28 September 1995 of the Oslo II [full name: The Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip].)

As to East Jerusalem, Rabin proposed that a Palestinian who resided in the West Bank but also maintained a second address in Jerusalem could become a member of the Palestinian delegation. Again, the Palestinians could claim that an East Jerusalem Palestinian is included in their delegation, while Israel could state that the Palestinian is a West Bank resident. Baker and his staff thought then that the two ideas proposed by Rabin could break the impasse over Palestinian representation, as they and the Egyptians were working with the PLO, while Rabin was discussing these ideas with Prime Minister Shamir.

However, on 5 March 1990, the Likud Party members of the national unity government rejected Rabin’s ideas which had by then been adopted by Baker in his modified Five Points Plan. Ten days later, on March 15, 1990, the national unity government collapsed, and Rabin and his fellow Labor Party members moved back to the opposition in the Israeli Knesset. Rabin’s Peace Initiative thus died.

From Rabin’s 1989 Peace Initiative to His 1993 Oslo Accords

Two years later, in June 1992, the Labor Party led by Rabin defeated Shamir’s Likud Party, making Rabin Israel’s Prime Minister. A year later, Rabin began navigating the discussions in Oslo between a small Israeli team, which included me as Rabin’s ‘eyes and ears,’ and a PLO team. These discussions eventually led to the Oslo Accords. Many of the ideas that Rabin first raised in his 1989 Peace Initiative (and which Shamir’s Likud then blocked) were used in the Oslo Accords. So, Rabin did not suddenly change in Oslo. Rather, he finally found a Palestinian partner with whom he could implement his old ideas.

Rabin and the PLO

Some commentators have suggested that Rabin’s real transformation in Oslo occurred because it was there that he first agreed to talk with the PLO. It’s true that previously Rabin had opposed talking with the PLO and he had expressed this view repeatedly and strongly, so Oslo indeed marked a watershed in Rabin’s approach to that organisation. But a closer look at Rabin’s attitude toward the PLO demonstrates that the change did not occur instantaneously in Oslo. Rather, Rabin’s transformation occurred gradually and had commenced years before Oslo.

Thus, in 1989, years before Oslo, when Rabin still opposed talking directly with the PLO but also understood that his Peace Initiative could not be advanced without PLO support and that to obtain that support there was a need to allow some PLO involvement in the Palestinian delegation, Rabin came up with the idea of including a PLO-affiliated member in the Palestinian negotiating team. And Rabin knew very well that while he was negotiating the composition of the Palestinian delegation with Egypt and the United States, they were passing his ideas to the PLO and passing PLO responses back to him – meaning that he was already indirectly talking with the PLO.

Rabin’s decision to talk directly with the PLO in Oslo, therefore, was not a quantum leap. Rather, it was simply the result of Rabin’s conclusion that continuing to talk with non-PLO Palestinians was a waste of time, because those Palestinians were actually controlled by the PLO, and the PLO would not allow them to reach a deal with Israel if Israel did not talk directly with the PLO.

Rabin’s Strategic Vision

Most importantly, Rabin wanted to reach a deal that would bring peace to Israel on its Eastern front. In 1973, after Rabin returned to Israel following his service as Israel’s Ambassador to the United States, he famously stated that, as much as he felt a strong connection to the West Bank (which he referred to in its biblical name, Judea and Samaria), he could see himself visiting Gush Etzion in the future with a visa stamped in his passport.

To fully grasp how dovish this statement actually was at the time, one must understand that Gush Etzion is a West Bank area adjacent to the Green Line which, prior to the 1948 war between Israel and Jordan, was populated by several Israeli towns and villages that Jordan captured during the 1948 war, with all of its Jewish residents and defenders either massacred or taken as prisoners of war. When the IDF conquered the West Bank from Jordan in 1967, Gush Etzion was the first area in which Israel established settlements, populated primarily by the survivors of the same Jewish families that had lived in Gush Etzion prior to its capture by Jordan. So, for Rabin to identify this area as one from which Israel would likely withdraw in the context of peace, his attitude, commitment and length to which he was willing to go were clear – if he was willing to forego Gush Etzion for peace, he was willing to forego the West Bank.

I have already pointed out that when Rabin concluded the 1993 Oslo deal with Arafat, he understood well that the process that he put into motion would result in the creation of a Palestinian state. However, in his 1995 speech to the Knesset, he referred to that future entity as ‘less than a state’ not only to help in securing the necessary majority in the sharply divided Knesset for approving the Oslo II agreement, but also because of his strategic preference for the creation of a link between the future Palestinian entity and Jordan and because he thought that Israel should continue to play a role in maintaining security in the West Bank and Gaza even after the permanent status agreement would be reached. For Rabin, therefore, the reference to an ‘entity less than a state’ was simply a shorthand for ‘a Palestinian state that would be permanently linked to Jordan and in which Israel could play a security role.’

Indeed, throughout his life, Rabin remained dovish on the ultimate fate of the West Bank and Gaza, while also insisting on strict security arrangements to protect Israel. His actions and positions stated publicly regarding security and peace issues demonstrate how interlinked he saw these two necessities. A statesman, soldier and leader, he was uniquely the perfect person to steer Israel’s pursuit of peace. No wonder that his assassination 25 years ago dealt a serious blow to the peace process – a crime which today appears to have irreversible consequences.

Annex

Main Elements of The Minister of Defense’s Policy Plan for the West Bank and Gaza

(A draft that Joel Singer helped develop for Yitzhak Rabin in early 1989 based on discussions with Rabin)

Israel has two partners for negotiations and peace agreement on our Eastern border: Jordan and representatives of the West Bank and Gaza Palestinians. They will both be equal partners in the negotiations with Israel.

The PLO cannot serve as a party to the negotiations with Israel because of its demands to establish an independent, PLO-run state and for implementation of the ‘right of return,’ both of which endanger the existence of Israel.

The Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza possess a defined political identity and constitute a separate people. They are the main carriers of the struggle and suffering and, therefore, are entitled to have their fate and future determined in a political process in which they will participate in a central manner.

All the Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza that will be elected by the residents to represent them are legitimate partners in the negotiations with Israel regardless of their views.

The Palestinian representatives in the negotiations with Israel will be elected in entirely free elections. The elected Palestinians will constitute a political representation. We are not talking about elections of mayors on the basis of a municipal platform.

In order to ensure free elections, a few conditions must exist:

- The elections will take place after a period of calm, lasting 3-6 months.

- Israel will initiate several steps whose purpose is to increase the trust of the residents of the territories in the seriousness of Israel’s intentions and will encourage them to contribute their share to the tranquility.

- Steps will be taken to prevent pressures and threats by the terrorist organisations on the exercise of free elections.

- Israel too will not attempt to influence the elections results. In order to accomplish this goal, we will be prepared to consider various ideas, such as elections supervision committees comprised of residents of the territories, redeployment of IDF forces from the polling stations areas on the day of the elections, etc

- Elections candidates will be given full freedom of expression in order to allow them to present their platform before their constituents.

The negotiations between Israel, Jordan and the elected Palestinians will be conducted without any pre-conditions.

The conflict resolution will be accomplished by Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian representatives in two phases:

- In the first phase, an agreement will be concluded between Israel and the elected Palestinian representatives in which the residents of the territories will be granted expanded autonomy for a transitional period. That is, they will be able to manage their daily lives themselves. In this period, Israel will be responsible for security in the West Bank and Gaza. The Israeli settlements will remain in place during the transitional period. The manner by which the self-governing authority will function and all other details relating to the transitional period will be determined in the autonomy agreement.

- During the transitional period, negotiations will commence between Israel, Jordan and the Palestinians regarding the permanent solution that will be established following the transitional period. The permanent solution will cover peaceful relations, security arrangements, borders, Israeli settlements, and the links between the West Bank and Gaza and their residents with Jordan and Israel.

The Minister of Defense believes that the United Nations should not get any management role in the West Bank and Gaza either during the transitional period or in the context of the permanent solution (beyond its current responsibility for providing assistance to Palestinian refugees through UNRWA); rather, all the governmental functions that, according to the agreements, will no longer be exercised by Israel will be placed in the hands of the Palestinians and Jordan, all as will be agreed.

The Palestinian refugee problem will be resolve in the context of a separate international conference that will convene immediately after a permanent solution for the West Bank and Gaza has been reached. This conference will address all issues related to the Palestinian refugees residing outside the West Bank and Gaza, as well as the Jewish refugees from Arab countries.