Rabbi David Stav, head of the Orthodox Tzohar organisation, has called for fasting as a response to the polarisation in Israeli society over the judicial reform. Khinvraj Jangid applauds and offers a Gandhian perspective on the value of fasting as a method of political struggle, and of political healing.

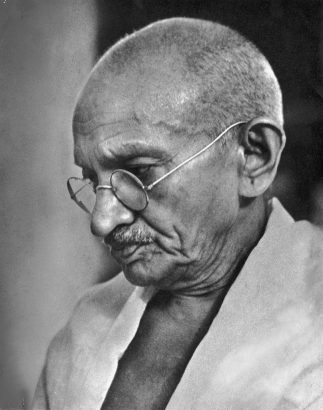

When he was assassinated, Mahatma Gandhi was fasting in Delhi for peace and reconciliation between Hindus and Muslims. His last fast was his longest, the six days of 13-18 January 1948.

Mahatma Gandhi had fought British Imperialism and seen India liberated in his lifetime, but his fight against those social evils that emanated from within Indian society, not least religious sectarianism and the caste system, was ultimately a failure. Trying to propagate peace, forgiveness and non-violence he lost his life to an ultra-Hindu nationalist who was in thrall to hatred and revenge after the partition of India, and who found Gandhi too kind and forgiving to Muslims.

Gandhi was an original political activist and thinker – he coined a specific language of political struggle, and he defined his own political methods. Fasting was one of his greatest discoveries as a tool for resistance, reform and for reaching out to his political opponents. Before Gandhi, fasting had been a deeply private affair for the religious; it remains a common practice in everyday religious Hindu life. Indeed, most religious practices, including Judaism, have combined prayer with certain degree of fasting.

Shocking then, and still today, Gandhi turned the personal religious practice of fasting into a political tool adopted by the masses in their political struggles in India. In public life, he fasted eighteen times and called fasting ‘a part of my being. I can as well do without my eyes, for instance, as I can without fasts. What the eyes are for the outer world, fasts are for the inner’.

But what has fasting got to do with Israel’s current political battles?

Haaretz carried the plea of Rabbi David Stav, Tzohar founder – who, like many Israelis, is deeply worried as he watches Israel approach the political abyss – that Israelis should adopt fasting for a day. He believes fasting can help ‘leadership on both sides to find a way to talk, to stop the legislation and the protests [in order] to enable the leaders and society to take a break and recover from this tension and enable them to sit together and talk’. ‘It’s actually a very modest request’, he added.

In fact, fasting is one of the most innovative mechanisms through which people have pursued change or resisted power. Like Gandhi, Rabbi David Stav presents fasting as a sacred thing, akin to prayer. Gandhi said, ‘I believe that there is no prayer without fasting, and there is no real fast without prayer.’ Fasting is more than prayer though. People in prayer can suffer from inaction whereas people on fast are resolute and totally committed to the cause.

It is fascinating to me that a religious leader like Rabbi Stav came up with the idea of fasting as a response to the crisis in Israel. It is less of a surprise that the liberal-left-democratic agents of resistance almost missed this suggestion. Yes, they know their goals and they are charged up enough to bear any costs. There have been many unique symbols and methods of resistance adopted in Israel in recent weeks, such as civil disobedience (another Gandhian tool), peaceful marches and the ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ displays. But they err in not engaging with the religious bent of mind. They might instead be thinking what religion can offer them.

Gandhi taught that the act of fasting, as a tool for political purposes, is not about launching a fight against someone. Gandhi explained, ‘fasting can only be resorted to against a lover, not to extort rights but to reform him, as when a son fasts for a father who drinks. I fasted to reform, say, General Dyer [British Officer who gave orders to shoot at a large and peaceful gathering, killing hundreds in Punjab in 1919] who not only does not love me, but who regards himself as my enemy’. So, fasting is an act that seeks transformation of the other, the ‘perceived enemy’. It extracts a desired outcome by coercing the other by showing one’s own physical suffering. The Palestinian prisoners have exercised such a form of resistance for long with their hunger strikes.

Second, fasting can help us keep our eyes on the prize which is not winning the battle but winning the war – i.e. the good health of the democracy, of the nation, and overcoming religious and ethnic and political schisms.

Third, the act of fasting is based on the presumption of good faith in the other whom one is supposedly ‘fighting’. Gandhi believed one has to ‘overcome evil by good, anger by love, untruth by truth, himsa (violence) by ahimsa (non-violence)’. This is a most difficult challenge as it means transforming one’s own emotions in the middle of the battle, learning to look at ‘the other’ with understanding and empathy. He believed this could create an opening for dialogue and for compassion between those in the fight. Perhaps acts of fasting can help Israelis – no more, but equally, no less – to facilitate a meeting point for all those who now enter a breathing space, seek to dialogue together, and anticipate a reactivation of a judicial reform bill in due course; this time, hopefully, with compromise and consensus.