Speaking at a private forum in late 2018, Director of the Institute for National Security Studies, Maj. Gen. (ret.) Amos Yadlin presents an overview of the different regional threats facing Israel as well as the ongoing challenge of the Russian presence in the Middle East. Below is an edited transcript of his remarks. Download a PDF version here.

Introduction

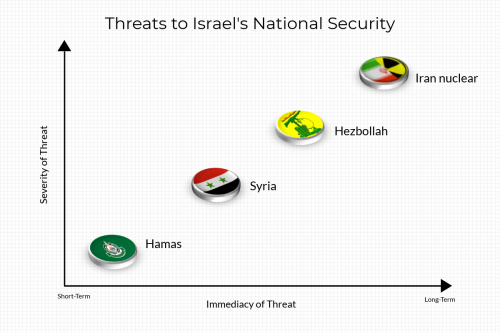

Israel faces numerous strategic security challenges both on its borders and hundreds of miles away. Its main security challenges come from Hamas in Gaza, Iran’s entrenchment in Syria, Lebanese Hezbollah, and Iran’s nuclear ambitions. In order to fully understand the scope of these threats, one must analyse them on a scale of immediacy and severity [see infographic 1]. Hamas is the most immediate threat Israel faces, but the least severe. The next most immediate threat is the Syrian civil war coupled with Iran’s entrenchment in the country. After that comes the medium-term threat posed by Hezbollah, a far more severe challenge. The most severe and long-term threat Israel faces is Iran’s nuclear ambitions. This essay will analyse the scope, severity, and immediacy of these threats.

Infographic 1: Threats to Israel’s National Security

The threat from Hamas

When analysing the situation in Gaza, one cannot disconnect it from Israel’s other three main security challenges – the Syrian civil war, Hezbollah, and the Iranian nuclear threat. Israel’s decision not to enter a full-scale war with Hamas in November 2018 [after Hamas sent 500 rockets into southern Israel] cannot be understood without realising that there are far greater challenges the Israeli cabinet and defence establishment are worried about.

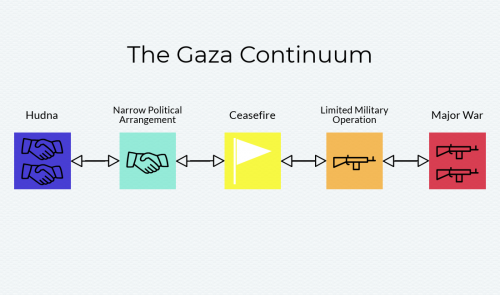

The threat Israel faces from Hamas is immediate, although the lowest on the scale of severity. Looking at Gaza, there are five potential scenarios: ‘full scale war’, ‘limited military operation’, ‘ceasefire’, ‘narrow political arrangement’, and ‘long-term agreement’ (or Hudna). [See infographic 2]

Infographic 2: The Gaza Continuum

Neither Israel nor Hamas want a full-scale war. Hamas understands the balance of power, remembers the destruction from the 2014 Gaza War, and recognises that another war would be devastating. From Israel’s perspective, another war does not bring many benefits as Israel is likely to end the war at the same point it started it – unless the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) decides to reoccupy Gaza, a scenario which almost no one in Israel is contemplating. Therefore, Israel must be prepared to carry out a strike severe enough to weaken Hamas and return calm to the strip, and restore Israeli deterrence, which at the same time would not lead the parties to a full-scale war.

A long-term agreement, or Hudna, is not possible at the moment because the gaps between Israel and Hamas are too large. Hamas’s demands for a Hudna, essentially receiving everything without giving anything substantial in return, are far greater than what the President of the Palestinian Authority (PA), Mahmoud Abbas, wanted from a permanent peace accord. Hamas does not recognise Israel’s right to exist, rejects the agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and is not willing to renounce terror. It also wants the ability to re-arm and import weapons from Iran and other places, which is a serious concern for Israel.

In light of this, Israel and Hamas are basically moving between three situations – limited military operation, ceasefire, and a narrow political agreement. A narrow political agreement based on limited parameters – such as paying salaries of civil servants, limited openings of the crossings, providing more fuel and electricity to Gaza, enlarging fishing areas etc. – is achievable. In fact, most of the demands Hamas has made regarding a ceasefire relate to the lifting of sanctions imposed by the PA, not Israel.

The November 2018 exchange of hostilities between Israel and Hamas can be categorised as a limited military operation. Both sides were firing at one another, without escalating to all-out war (Israel carried out strikes against some 160 targets in Gaza, yet no Palestinians were killed, and Hamas fired 500 rockets at areas in southern Israel, but not to Ashdod or Tel Aviv). During such a limited military operation, the Egyptians and UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process Nickolay Mladenov hastily try to arrange a ceasefire, and while the parties reached one, they never agree on the terms of a ceasefire. This situation then allows Hamas to push the envelope, because they want better parameters for a limited political arrangement in the future. To get there, they arrange violent demonstrations at the Gaza border, which subsequently leads to more violence that may trigger another limited military operation. The danger is that it will not be limited – one misfired bomb or missile resulting in many casualties will force the parties to move from a ‘limited military operation’ to ‘major war’. The then Minister of Defence, Avigdor Lieberman, resigned because he wanted a severe strike against the military wing of Hamas, whist the rest of the cabinet opted for a ‘limited military operation’ and maybe a ‘ceasefire’.

No easy solutions

We belong to a culture that seeks a solution to every problem. In the Middle East however, there are some problems with no solutions and Gaza is among them – certainly when discussing a permanent or long-term solution. Hamas has failed economically, militarily, and politically – every conceivable parameter – to reach an agreement with the PA, and has lost the support of most of the Arab world, with the exception of Qatar.

Hamas wants a ‘narrow political arrangement’ that will revive the economy in Gaza – knowing they will not receive full freedom of movement because Israel wants guarantees that they will not smuggle weapons into Gaza. Hamas’s most recent success in getting 16 hours of electricity a day rather than four hours was a huge achievement for the group. In these agreements however, Hamas is negotiating to get more and give less.

Every time somebody asks the question of why Israel doesn’t reach a peace deal with the Palestinians, they need to ask what the parameters of such a deal would be. There are significant gaps between the different factions and groups involved, including between the PA in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza. So what are the possibilities for Gaza? If both Israel and Hamas remain in the ‘ceasefire’ scenario, Gaza can be calm for a couple of years, during which time Hamas will try to alleviate the humanitarian catastrophe it is currently facing – which is also in the interest of Israel. This is the reason why a right-wing Israeli government, which promised to destroy Hamas, is in fact negotiating indirectly with the terrorist group. Politically, the question of a peace deal with the Palestinians is a much larger issue than Gaza. The central questions are: What will Trump’s peace plan be? Who will be the next leader of the PA after Abbas? And who will be the next Israeli prime minister? As there is no clear answer to these questions, at the moment, the best scenario for Israel and Hamas is adhering to a ceasefire.

Iranian assets in Syria

The outcome of the Syrian civil war has been decided although the conflict is still ongoing in two areas controlled by the rebels and Kurdish forces, supported respectively by Turkey and the US. Additionally, much of the country will necessitate reconstruction once all fighting has ceased. Iran’s presence in Syria, which is central to President Bashar al-Assad’s ultimate victory, remains a huge problem, as the Iranians have not ‘declared victory’ and returned home. This is because of Iran’s plans to build a formidable military force in Syria against Israel, consisting of precision guided missiles, ballistic missiles, land to sea missiles, UAVs, air defence systems, airfields and naval bases. Its plans were initially implemented in 2017-2018, and had Israel not taken the necessary action against Iran, its military build-up in Syria would be fully operational today. Just as Iran is determined to build up their power, Israel is unwavering in preventing them from doing so, which is a recipe for collision, conflict and escalation.

At the end of 2017, the Institute for National Security Studies predicted Israeli-Iranian collision in Syria, which subsequently happened in February of 2018 when Iran launched a UAV towards Israel with explosives, and Israel retaliated by attacking the T4 airfield in Syria. Iranian General Qassem Soleimani decided to respond, and between February and May, Israel prevented further Iranian action by carrying out additional attacks on Iranian assets in Syria. On 10 May Iran launched 32 missiles towards Israel. They failed, with 28 of them falling in Syria due to operational problems. Israel then destroyed almost 50 sites belonging to Iran in Syria. That led to the Iranians ceasing further retaliation for the time being. However, just like the NBA playoffs, while Israel has won the first game, there will be more to come and it is clear the Iranians have not given up.

In May 2018 Iran also had other pressing concerns – elections in Lebanon, Iraqi parliamentary elections which did not go according to their plans, and domestic, economic and social pressures. In September though, Iran returned and an Israeli preventative attack consequently led to the incident which resulted in the Syrian air defence shooting down a Russian reconnaissance plane.

Even so, Iran’s presence in Syria is not the most severe challenge facing Israel. As long as Israel continues to confront Iran only in Syria, Israel has an advantage – intelligence and air superiority and a relatively less dangerous arena to operate in. The Iranians are now likely regretting the choice of Syria as their main arena to fight Israel and are potentially considering relocating their operations to Lebanon and Iraq. This will be a more difficult challenge for Israel.

There are those in Israel who are under the illusion that the Russians and Iranians are conflicted over the future of Syria. Most importantly, the Russians and Iranians share common interests in the country. The two main goals of both countries in Syria are first, to push out the Americans and second, to keep Assad alive. These shared interests are the most important factor to their current co-operation, more so than the question of who will have more influence in Syria in the future.

As such, Israel knows that Iran will not be removed from Syria by the Russians or the Americans. The American forces currently deployed in Syria only have the authorisation to open fire at ISIS forces, not Iranian ones. Second, the Americans do not have an appetite for another conflict in the Middle East. In this respect, US presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama are very similar, as they look to withdraw US military forces from the region. The question then is whether Israel can remove Iran from Syria. It can. However, if Iran moves its operations against Israel to Lebanon and Iraq and if due to the presence of Russian forces in Syria, Russians are caught in the crossfire, it would become a different ball game.

Hezbollah missiles and the Precision Project

The third and even more challenging threat facing Israel is Hezbollah, which has a stronger and much larger capacity in Lebanon than Iran does in Syria. Israeli deterrence vis-à-vis Hezbollah is very strong and Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary-General of Hezbollah, will do everything in his power to prevent a third Lebanon war.

Between February and May 2018, when Iran was struggling with its operational plan against Israel from Syria, Iran approached Nasrallah, who in turn told the Iranians that Hezbollah was not ready to attack Israel. While Iran did not further pressure Hezbollah to strike Israel, ultimately, if Iran does decide to retaliate against Israel, its only effective tool to do so is Hezbollah. Iran will remind Nasrallah of its financial support over the last 20 years – between half a billion to a billion dollars a year – and how it has provided the organisation with weapons and training. Within Hezbollah’s many identities and commitments, its commitment to Iran is dominant, so Iranian demands will be hard to ignore. While not the most immediate threat, it is one of the most significant. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s UN General Assembly speech in September 2018, during which he showed pictures of the Iranian and Hezbollah factory sites which moved from Syria to Lebanon, underscored the severity of the threat.

The Precision Project is key to understanding the gravity of this threat. This project is Iran’s grand plan to be more effective against Israel conventionally and involves plans to upgrade thousands of missiles and rockets in Hezbollah’s arsenal, incorporating precision guided technology that would allow the missiles to land within 5 to 10 metres of their target. This changes the scope and severity of the threat towards Israel. The Precision Project started in Syria and was foiled by Israel, but is now shifting to Lebanon. That’s what makes Hezbollah a serious potential threat in 2019.

Israel faces a crucial decision. Doing nothing will result in Hezbollah presenting a significantly more serious threat over time, making a third Lebanon war much more difficult for Israel. Alternatively, Israel could pre-empt the increase and advancement of their capabilities in a similar fashion to what they did with Iran’s military build-up in Syria over the last two years. This is a very serious decision facing the Israeli cabinet.

The Iranian nuclear challenge

The final and most severe threat is that of the Iranian nuclear challenge, but it’s a long-term problem. The Iranian nuclear weapons programme can be renewed at any point and following President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran could decide to follow suit and leave the agreement. However, Iran is navigating this situation with extreme caution, hoping that Trump will be side-lined and the rest of the world will not join him in sanctioning businesses that trade with Iran. The secondary sanctions introduced in November were much more effective than expected, and the Iranians may find a way to bypass them or reduce the effects.

The two important questions here are not whether sanctions have an effect (they do), but whether the effect is painful enough for the regime to change its behaviour. The Iranians are waiting for the return of a Democratic president to the White House and plan to absorb the effects of sanctions until then. It will take time to see if the sanctions are painful enough. Iran’s ‘economy of resistance’ has faced sanctions for the last 40 years and developed mechanisms for bypassing them. In doing so, Iran has amassed a huge foreign currency reserve that will help them overcome the impact of sanctions for at least two to four years.

The second question is what Iran will do if sanctions are painful enough. Will it lead to regime change or force them back to the table to renegotiate a new deal? Most likely not. One challenging scenario would be for Iran to return enriching uranium under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as they did over the last decade before signing the JCPOA. After seeing how Kim Jong-un and North Korea were treated, Iran might decide that coming to the negotiating table with a bomb may be the best course of action. However, there are risks in this approach, as they could lose European support and even Russian support. This scenario would be a significant challenge for Israel.

Regime change in Iran is highly unlikely

The Egyptian revolution presents an interesting case study when trying to examine the likelihood of regime change. In Egypt, the military stopped supporting President Mubarak, the religious establishment was opposed to his rule, and the economic and social situation was deteriorating. Unlike Egypt, in Iran the military still strongly supports the regime, (militarily, there is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which is stronger than the Iranian military and extremely loyal to the regime.) Moreover, the religious establishment continues to support the regime. In fact, the regime is the religious establishment itself. However, Iran is experiencing economic and social problems. The economy is not in good shape, although the main opposition is from the lower class, which is not strong enough or centralised to pose a serious threat to the regime. The middle class has seen what civil wars have done to other countries in the region – Syria, Iraq, and Libya. Unlike those countries, Iran’s middle class has not reached a desperate enough situation where they feel they have nothing to lose, at which point they may perhaps demand regime change.

Will there be organised international intervention, which was the mechanism for regime change in Libya? This will never happen in Iran. Even the US, which is the most hawkish towards the Iranian regime, says that behavioural change, not regime change, is their goal.

Q&A

What is the current relationship between Israel and Russia?

Today, Israel and Russia have a normal relationship – in a way a lot more normal than what the rest of the world has with Russia. Prime Minister Netanyahu often visited Moscow during the Obama presidency – it looks as though he preferred to go to the Kremlin over the White House.

Following the downing of the Russian plane, President Vladimir Putin gave Netanyahu the cold shoulder, yet Israel and Russia are not enemies – there are nine flights every day from Tel Aviv to Moscow, there are a million people in Israel who came from the former Soviet Union, and Putin does not support Iran’s claim to destroy Israel.

While Israel has established a very efficient de-confliction mechanism with Russia in Syria, Israel doesn’t ask the permission of the Russians to act there, nor do Israelis coordinate with them. The de-confliction mechanism was set up to avoid misunderstandings and mid-air collisions on both sides. Israel gives them a notification via a hotline manned by a Russian speaking Israeli officer talking to a Russian officer in Syria. Although it was not the intention of Russia’s intervention, the unfortunate strategic result of Russian activity in Syria has been the accumulation of Iranian and Hezbollah fighters closer to Israel.

Russia has accepted that Israel will attack Iran and Hezbollah in Syria on two conditions: first, that no Russian soldier gets killed; and second, that Israel doesn’t topple the Assad regime. Israel’s strongest card in Syria was its ability to end the Russian goal of saving the Assad regime. There is no doubt that Russia now wants to stabilise and reconstruct Syria, but with someone else – the Europeans, Americans, Chinese – paying for it. The stability that the Russians want is threatened by an Israeli-Iranian confrontation. Putin is likely telling Netanyahu to wind down the number of the attacks while saying to the Iranians that they are bringing the Israelis into Syria.

The S-300 threat

Russia’s behaviour after the downing of its reconnaissance plane was odd as it was a Russian missile, fired by a Syrian air defence operator (perhaps with a Russian advisor in the vicinity), that downed the aircraft – but they blamed Israel. The Israelis gave the Russians an early warning prior to attacking the Iranian installation near Latakia. Twenty five minutes after the attack, when Israeli jets were already back in Israeli airspace, the Syrians decided to shoot down what turned out to be a Russian airplane which, at the time of the attack, was 150km from the area targeted by Israel. When it was shot down however, the Russian plane was closer. This is an elementary mistake by the air defence operator who was unable to distinguish between foe and friend, and while it was beyond a shadow of a doubt a Syrian mistake, the Russians blamed Israel. The Russians then subsequently announced they were sending the S-300 air defence system to Syria.

We should pay attention to the difference between the tone and statements of the Russian defence establishment – those who are in Syria and involved with the Iranians and Syrians in the same war against a common enemy – and the Russian president. Putin’s first reaction was that a mistake had been made, but that it was not a crisis. The Russian defence establishment, however, took a much tougher position. Most likely, it was the Russian defence establishment that ultimately convinced Putin be tough, and to send the S-300s to Syria.

With the deployment of the S-300s there are now three possible scenarios. The first scenario, (currently the case) is that Russia sends the S-300s to Syria but keeps them under their control, thereby not allowing the Syrians to operate the system. Recent satellite pictures show that the S-300s are not operational – still under camouflage netting. In this scenario, nothing has changed relating to Israel’s ability to operate in Syria. The Russians have had the S-400 deployed in Syria since 2016 (when Turkey downed a Russian plane), which is a much more advanced system. So long as the S-300 system remains under Russian control and the Russians do not change the rules of engagement, nothing in terms of Israel’s ability to operate in Syria has changed.

The second possibility is that the Russians give the system to the Syrians at which point everything depends on what the Syrians do and whether they will fire at Israeli planes. If this happens, it is likely that the S-300 system will be destroyed by Israel. The S-300 is a better air defence system than anything the Syrians currently have, but the Israeli air force can deal with it.

A more problematic scenario would be the Russians changing the rules of engagement for their own forces, or creating mixed Russian-Syrian forces. If there is something Israel doesn’t want to happen in Syria, it is the death of Russian soldiers. This scenario would create a different environment, one in which it would be far more difficult for Israel to end Iran’s presence in Syria.

Comments are closed.