Centrism is ‘the antidote to the extremism and sustained attacks on liberal democracy that are sweeping much of the democratic world.’

So writes Yair Zivan, the editor of this timely volume, setting out the overarching message of this book in his introduction.

Many of the essays that follow do indeed make this argument, often compellingly. But no less importantly, they spell out why centrism should be taken seriously, and not dismissed as “mushy moderation” as it so often is by both progressives and conservatives.

It’s not hard to see why that criticism is made. One consistent thread running through the book, repeated in some version by almost every contributor, is that centrism must be “effective”. It must be – in part at least – “what works”. For example, former Norwegian foreign minister Børge Brende writes, ‘Like much else in the centrist approach, the case for centrist global collaboration is strong because it has been shown to be effective.’ Former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull lauds centrism as ‘harnessing and implementing good ideas… if they come from the left or the right, to be as effective as possible.’

“What works” can seem to some to be indistinguishable from “whatever works”; a principle-free, intellectually vacuous technocracy. And though this is an unfair reading of what is being argued here, those of us sympathetic to centrism must concede it’s an easy mistake to make.

Centrism as pluralism

In fact, Yair Lapid, in one of the least fuzzy essays in the collection, ‘The Case for Centrism’, criticises centrism – or, perhaps, some centrists – for failing ‘to present a conceptual alternative’ to the extremes of left and right. For Lapid, centrism can sometimes ‘present itself as a faded version of the left or the right, instead of insisting that it operates under completely different rules of engagement and in a completely different political field.’ He accuses centrist parties of being too frightened to distance themselves from right or left, lest they lose voters. In such a scenario, voters often ignore them and vote for the real deal.

Lapid‘s centrism (which I find personally appealing) is a response to a new reality, where, in his words,

The separation into right and left is artificial and outdated, and the real struggle is between the moderates and the extremists…We are not looking for the ideal way of life; rather, we seek to create the conditions that will allow different ways of life to coexist. The major challenge of the centre is to explain that moderation is not a compromise between world views – it is a world view in its own right.

Centrism here is pluralism, a rejection of ideologies that say how we should live. It’s a sensibility with liberal democracy as its sine qua non.

Moderation and heterogeneity

Lapid’s claim is further bolstered by other voices in the book. The long-time Washington Post columnist Jennifer Rubin (who identified as a conservative before her abhorrence of Donald Trump led her to decisively break with the American Right) defines centrism as ‘moderation + heterogeneity’ in her piece, ‘Centrism and the Fight for Liberal Democracy’. Centrism, for Rubin, understands that ‘wisdom does not exist solely on one side or another… Conservatives have something to offer in commending the benefits of free-market capitalism while progressives’ devotion to equal opportunity… has value as well (all, of course, in moderation).’ She makes the critical point that centrism can only exist in a liberal democracy where there is ‘an unavoidable tension between individual rights and popular sovereignty.’ My own addition to her argument is the obvious-but-easy-to-ignore fact that autocracies can be either left or right, but – almost by definition – never centrist. Centrism requires pluralism and the willingness to bring people and ideas together from opposite sides of the aisle.

The list of contributors brought by Zivan – an advisor to Lapid and former International Media Spokesperson for President Shimon Peres – includes a number of former statesmen and political leaders, but one of the few currently serving government ministers in the book is German Justice Minister Marco Buschmann. If Rubin’s centrism is about moderation and heterogeneity, Buschmann’s essay ‘Centrism and the Rule of Law’ discusses a duality of ‘the intrinsic value of each individual’ (as opposed to seeing people as part of a political, class or ethnic tribe); plus cooperation (as opposed to constantly looking for a political enemy to fight). Where he agrees with Rubin is in the importance of liberal democracy, and specifically the rule of law, which Buschmann views as critically important to centrists. He’s by no means the only contributor to reiterate Zivan’s call for centrism as an “antidote” to today’s extremism, but he does so more directly than most, arguing against what he sees as the tyranny of the majority and Viktor Orban-inspired illiberal democracy. ‘The law sets limits that protect the individual, even against the majority. For a majority that wishes to rule unfettered however, the law is an obstacle.’ Buschmann explains.

Centrism – an Israeli angle

It’s an argument which could have been written with Israel’s power-grabbing judicial “reform” in mind. Those of us in Israel who spent our Saturday nights in the ten months prior to 7 October demonstrating against our government, would recognise ‘a majority that wishes to rule unfettered’ as a perfect description of Netanyahu’s illiberal/theocratic coalition.

Lapid and Zivan are not the only Israeli contributors to the book. Polly Bronstein, a social activist and author of ‘How I Became a Moderate – A Journey from Left to Center‘, argues in her essay, ‘The Centrist Method’, that, ‘at the core of the political centre lies national liberalism’ (or, as she immediately re-phrases it in the next sentence: ‘liberal nationalism’.) In Bronstein’s words ‘it is only a combination of the two, nationalism and liberalism, that meets both basic components of citizens’ identities in the modern nation-state.’ (I made a similar argument in a 2020 essay ‘The Case for Liberal Nationalism’.)

Not incidentally, the central argument of my own essay was that liberal nationalism – like the “centrism” being promoted by most of the contributors in this book – offers a solution to the extreme polarisation of this historical moment. (Also not incidentally, my article was cited by none other than Yair Lapid when he laid out his centrist manifesto, with a title foreshadowing this book: Only the center can hold.) Indeed, it’s worth noting that Israel’s first “right wing” prime minister, Menachem Begin explicitly defined himself as a national-liberal; while the most scholarly case for liberal nationalism has come from a left-wing Israeli academic-turned-politician, Yael Tamir. While there would have been serious policy disagreements between these two, there was broad agreement on the fundamental principles of liberalism and nationalism, which informed both of their worldviews. One can therefore imagine pragmatic, ‘centrist’ compromises being reached between them, with both remaining true to their core values.

Different circumstances require different solutions

Another high-profile Israeli contributor is Micah Goodman. Arguably Israel’s most influential public intellectual, his book Catch 67 is the centrist analysis of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Goodman’s essay, ‘Faith, Philosophy and the Foundations of Centrism’, appears in Part 1 of the book, which seeks to define centrism. It’s a fascinating piece, drawing on his encyclopedic knowledge of both classical and Jewish philosophy. He contrasts two Greek approaches to centrist thinking, one which posits the centre as equidistant between left and right, the second which advocates a politics combining both left and right. He then suggests a Jewish approach, different from both, derived from the book of Ecclesiastes: “To everything there is a season” (if you don’t know your Bible, you may know the hit song it inexplicably inspired, by the Byrds.) A centrist understands that in the real world, there will be times when the right makes more sense, and times when the left does, as opposed to what Goodman terms ‘zealots’ of right or left who are ‘focused on their own world view and fail to notice what is happening in the real world.’ (Though he doesn’t spell it out, this is essentially Goodman’s critique of the right and the left in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The right ignores the threat that permanent occupation poses to Israeli democracy; the left pushes for “peace now”, even following three failed rounds of negotiations spanning decades and with a partner as manifestly unreliable and suspect as the Palestinian Authority.)

Goodman’s account adds an important plank to the centrist argument: centrism is not only about pluralism, liberal democracy, and the willingness to compromise; it’s also about recognising that different times and different circumstances require different solutions. That is not to say that principles don’t matter. Rather, as the American academic Charles Whelan argues in his essay ‘Centrism and Building a Better Political System’, centrists pursue their principles and passions in ways that might require compromise; not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Finishing the essays, I was left with one overriding thought, and one question. The thought is that this really is a book for the current historical moment. In Israel, the United States, and countries across Europe, liberal democracy is in dire need of protection. And what so many of the essays make clear is that those best equipped to do so are those who can place ideology to one side, and pursue pragmatism and a no-frills agenda of good governance in the national interest. Liberalism combined with patriotism; Willingness to work with a broad range of partners; Commitment to pluralism and live-and-let-live politics; Acceptance of the world as it is, not as we might choose it to be.

And the question: What does centrism mean in post-7 October Israel?

The traumatising events of that day, and the ensuing war we remain mired in eight months later are not addressed here, with the manuscript submitted before 7 October. In only one essay, written by American Jewish philanthropist Daniel Lubetzky, was an explicit reference to those events subsequently added.

Although the book’s publicity emphasises the timing to the recent European Parliament elections, and the British and American elections, it’s surely not incidental that it was compiled and edited by an Israeli.

In Israel’s chaotic multi-party system, centrism has played a key role, not just with the emergence of consequential centrist parties like Kadima and Yesh Atid, but also when buried beneath the ostensibly black-and-white binary of “left vs. right”. Whilst it’s true that in its first few decades Israel was run by a socialist-dominated government, when that monopoly was broken in 1977 by a “right-wing” party, it was that party that quietly shifted towards the centre over the decades it sat in the Opposition; Menachem Begin’s Herut first merged first with the Liberal Party and then with smaller centrist parties (including, bizarrely, one established by Begin’s arch-rival David Ben Gurion). As noted above, Begin never referred to himself as “right-wing”, but as a “national-liberal”.

When Labour returned to power in 1992 under Yitzhak Rabin, it was a Labour Party which accepted the privatisation reforms of the 1980s and had no wish to turn the clock back. And despite how he is now remembered, post-Oslo Accords, Rabin’s popularity in the country was not a result of some ‘peacenik’ reputation (he had no such reputation), but rather because of his hawkishness and record as a no-nonsense IDF General and then Defence Minister.

The reality is that almost all Israeli coalitions since then have included parties from left and right. The extraordinary political success of Benjamin Netanyahu, so long demonised abroad as a right-wing extremist, has been partly a result of his record as a cautious pragmatist. Until the formation of his current coalition in 2022, he always sought to establish governments with parties to his right and his left. It was precisely Netanyahu’s worsening legal situation and desperation to stay in power that worried those of us thinking and writing about the health of Israeli democracy. As he became increasingly dependent on the ultra-orthodox and the far-right, it was clear that his next government would be a decisive break from his previous, more ‘centrist’, tradition. And so it proved.

Echoing Polly Bronstein’s essay, Goodman has written and spoken in recent months about how the majority of Israelis have a sensibility which includes both liberalism and a strong national, patriotic feeling. It’s no coincidence that the same people who led the pro-democracy protest movement were behind the extraordinary civil society effort in the days after 7 October, to get food and supplies to Israelis displaced from their homes. Ordinary Israelis who had marched in their hundreds of thousands (wrapped in Israeli flags) against a government planning to institute an illiberal regime, rushed to their army bases to fight Hamas and Hezbollah.

The general perception of Israel is that it’s an increasingly “right-wing” society. I disagree. It’s a hawkish society; unwilling to take the risks for peace that many of our friends say we must, because we’ve had our fingers burned once too often – in the inferno of the Second Intifada; and now, in the hell of Hamas’s barbarism. It’s a society that believes in a strong military; because without one, we would simply not survive in this part of the world. It’s a society where religion is more important to more people than in most Western countries; because we’re patriotic, and, for Jewish Israelis at least, our national identity is tied up with religious traditions and customs. This is even more the case for Jews descended from the traditionally-minded immigrants from the Arab world (Mizrachim), today a majority of the country’s Jewish population.

But we also care deeply about individual freedom. The parties of the far-right and the ultra-Orthodox combined are currently polling at around 20 percent of the country. The dominant party for so many years, the Likud, which historically attracted the moderate right, is losing popularity. Its drop in the polls – though steeper since 7 October – actually began nine months earlier after the judicial reform proposals were first announced. When I interviewed Hungarian and Polish activists who had fought against the growing authoritarianism in their countries, they expressed envy and admiration for how so many ordinary Israelis had gone to the streets in the name of freedom and democracy. A Polish law professor admiringly referred to what he called Israelis’ ‘constitutional habit of heart’. Notwithstanding that we have no constitution, so many Israelis instinctively rebelled against what they saw as an existential threat to Israeli liberal democracy.

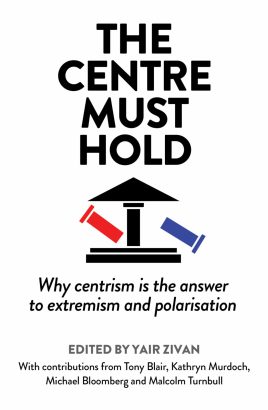

There are 36 essays in ‘The Centre Must Hold’, and Yair Zivan has done a fine job corralling them into themes and framing each section appropriately. There’s an inevitable lack of consistency in style, and certainly not every essay will grip or inspire every reader. But it’s strengthened my own centrist convictions, and my hope that Israel’s centrist (or national-liberal) majority, can bring about new leadership and the change we need in this country.