Israel, as Amos Oz once observed, was born out of a spectrum of dreams and visions, blueprints and masterplans. Some complementary, some contradictory, these dreams represent the federation of ideas that compose Zionism. Where these dreams quarrel with one another, there is the basis of political debate in Israel today.

In Like Dreamers, Yossi Klein Halevi examines the history of two dreams in particular: the kibbutz movement, that utopian ‘attempt to transcend human nature, replace selfishness with cooperation,’ and religious Zionism. Secular kibbutzniks and religious Zionists ‘disagreed about God and faith and the place of religion in Jewish identity and in the life of the state.’ Yet, Klein Halevi observes: ‘For all their differences, religious Zionism and the secular kibbutz movement agreed that the goal of Jewish statehood must be more than the mere creation of a safe refuge for the Jewish people. Both movements saw the Jewish return home as an event of such shattering force that something grand – world transformative – must result.’

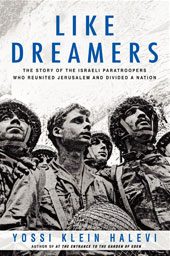

Klein Halevi cleverly and compellingly uses the lives of seven paratroopers – participants in the battle for Jerusalem during the Six Day War – to trace the development and ultimate decline of these two dreams. For it was June 1967 that brought religious Zionists and secular kibbutzniks together – ‘everyone had a share in the victory’ – before they would eventually part ways in the following months and years.

June 1967, for Klein Halevi, is the beginning of the end of the kibbutz movement. Those aligned with Mapam and Hashomer Hatzair lost their faith in the Soviet Union and Marxism. The Labour establishment of which the kibbutzim were part was exposed as corrupt and were caught off-guard on Yom Kippur 1973. ‘All the institutions and leaders I grew up believing in have failed,’ Arik Achmon of Kibbutz Netzer Sereni says. ‘The system that I was sure was foolproof has failed in every way.’ Materialism, individualism, and the occupation undermined utopianism and communal life, while Menachem Begin attacked the kibbutzniks as ‘millionaires with swimming pools.’

After 1967, religious Zionists perceived themselves to be the new pioneers: first in re-establishing the kibbutz of Kfar Etzion that was destroyed by the Jordanians in 1947; then, in forming new settlements in Samaria such as Ofra, Kedumim, and Elon More: ‘This time the movement would be led by religious Jews. There was no choice but to step into the void left by the depleted kibbutzniks. A movement of the faithful. All those who understood that Zionism was not about refuge but destiny, redemption.’

This narrative of the settlers usurping the spirit of the kibbutzniks, then losing it too, is not original. But through the stories of the paratroopers – poet-singers and Kookian rabbis, fanatical settlers and fanatical anti-Zionists – Klein Halevi manages to personalise and accentuate the transformation. His prose style, while occasionally purple, makes the history enjoyable and accessible, and Klein Halevi demonstrates empathy for both kibbutzniks and religious Zionists when it is demanded.

Unfortunately, where Like Dreamers loses steam is in the years after 1992, a period for which the predominant historical narrative has yet to be determined. Klein Halevi has his own thesis, namely that during the Second Intifada, Israelis turned away from both the peace camp and the settlers: ‘After three decades of vehement schism between left and right, a majority of Israelis now found themselves in an amorphous centre. In principle, most Israelis accepted a two-state solution and were prepared to make almost any territorial compromise that would bring about peace; in practice few believed that any territorial compromise could achieve that.’

To demonstrate that this is true, Klein Halevi has Arik Achmon – kibbutznik turned free-marketer – realise that the construction of the security barrier would ‘be a marker ending the utopian dreams of both greater Israel and Peace Now.’ Similarly, he tells us that Yoel Bin-Nun of Gush Emunim came to regard ‘both

the peace movement and the movement for greater Israel as utopian fantasists.’

Here we have a false equivalence. While Peace Now are ideological, they are neither utopian nor fantastical. Their positions on the core issues have been very much in the mainstream. Peace Now pushed for an inquiry into the mishandling of the Lebanon War, supported talks between Israelis and Palestinians during the 1990s, and today supports two states for two peoples. If Peace Now are utopian, then Klein Halevi would have to concede that most Israelis are utopian too.

He propagates this unsubstantiated comparison in order to suit his conclusion, which is also imprecise. There was indeed a quarrel between right and left for decades about whether, in the name of peace and security, to keep all of the land or give some of it up. The outcome of this disagreement was not, as Klein Halevi would have it, that both sides were defeated and a new centre emerged. Rather, the left won this argument, the mainstream right gave up the dream of a greater Israel, and the ‘amorphous centre’ or consensus thus emerged.

To assert otherwise is, in fact, to diminish and cheapen the transformation the mainstream right wing in Israel went through to acknowledge the necessity of giving up land for security, if not land for peace. After all, to relinquish the dream of a single state between the river and the sea – a dream imbued with tremendous historical and religious meaning – is far more significant, tumultuous, and heart-wrenching than, say, acknowledging that the Oslo Process had run its course.

The left in Israel might have altered its tone on peace, but the Labour Party has not changed its view that it is necessary for Israel to partition the land. On the right, meanwhile, Benjamin Netanyahu in his Bar Ilan address in 2009 reversed his long standing opposition and explicitly expressed his support for the creation of a Palestinian state. When it comes to the fate of Zionist dreams, noting this would make a more truthful and essential conclusion to Like Dreamers than the tepid and compromised ending Klein Halevi gives us.

Comments are closed.