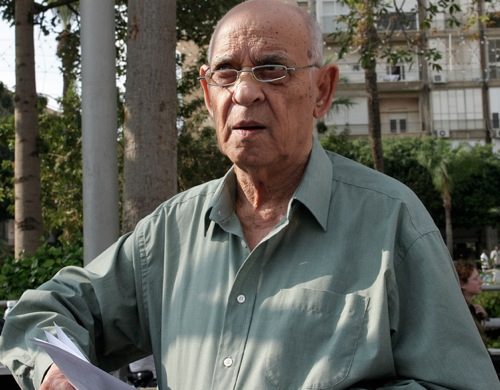

The Israeli novelist Sami Michael evolved from an Iraqi Jewish communist writing in his native Arabic language to an Israeli Jewish Mizrahi liberal writing in Hebrew. Noga Emanuel explores a body of work that is neither nostalgic for an idyllic exilic past in the ‘old country,’ nor sentimental about the present, but is the emblematic, ironic, unique, all-Israeli voice of ‘Otherness’ and edgy Israeli pluralism. This article was updated on 17/12/2014.

Three Vignettes

In November 1972, Orianna Fallaci sat down to talk to Israel’s then Prime Minister Golda Meir. The Italian journalist and author, one of the most original and controversial interviewers of her time, recorded Meir’s remarks in her 1976 book ‘Interview with History’:

We in Israel have absorbed about 1,400,000 Arab Jews: from Iraq, from Yemen, from Egypt, from Syria, from North African countries like Morocco. People who when they got here were full of diseases and didn’t know how to do anything. Among the seventy thousands Jews who came here from Yemen, for example, there wasn’t a single doctor or a single nurse, and almost all of them had tuberculosis. And still we took them, and built hospitals for them , and took care of them, we educated them, put them in clear houses, and turned them into farmers, doctors, engineers, teachers … Among the 150,000 Jews who came here from Iraq, there was only a very small group of intellectuals, and yet today their children go to the university. Of course we have problems with them – all that glitters is not gold – but the fact remains that we accepted and helped them.

… I think that none of us dreamers realised in the beginning what difficulties would come up. For example, we hadn’t foreseen the problem of bringing together Jews who had grown in such different countries and remained divided from each other for so many centuries. Jews have come here from all over the world, as we wanted, yes. But each group had its own language, its own culture, and to integrate it with other groups had been much more difficult than it seemed in theory. It’s not easy to create a homogeneous nation with people so different …. There was bound to be a clash. And it gave me disappointment and grief.

*

In the summer of 2011 Israel was roiled by a previously unknown phenomenon of popular mass protest against the impossibly high living cost in Israel. It started with mothers uniting against the price of cottage cheese and culminated in a ‘Tent movement,’ an Israeli cicurated version of the American Occupy movement.

Every group with a gripe joined the fray and soon enough all that simmering rage caused some proverbial fuses to blow up. Margalit Tzanani, an Israeli singer of Yemenite origin, shrugged at the young Israelis’ complaints about their life, ‘Some of the leaders in this protest movement are just pissed off because their grandmother did not leave them an apartment in Basel. It’s not a real thing,’ she dismissively opined. To which journalist Nathan Zehavi responded with typical Israeli composure: ‘Ms. Margol, who are you, you piece of nothing? I too have a sewer for a mind but it is at least an intelligent sewer. My grandma did not leave me an apartment in Basel. Do you know why? Because she was exterminated in Auschwitz.’ (Incident recounted in Gad Yair’s book The Code of Israeliness).

*

The Israeli poet Natan Zach was interviewed on Israel’s Channel 10 in July 2010. He faulted Mizrahi Jews, those whose parents and grandparents had immigrated to Israel from Muslim countries, with being inferior to European Jews: ‘The idea of taking people who have nothing in common arose. The one lot comes from the highest culture there is — Western European culture — and the other lot comes from the caves.’ The poet described his impressions of Israeli television, saying that ‘the Jews from the Oriental communities will understand the blacks and the Ashkenazis (European Jews) will get the bastards.’

A storm of indignation ensued, to which Haviva Pedaya, scholar and poet, responded by stressing that in her opinion, ‘The question is not when and why great poets like Natan Zach continue to give voice to the political unconscious that has dictated educational priorities in Israel, but rather when and why other great poets and writers — who came from “the caves” — will succeed in altering social and political awareness.’

***

These three vignettes demonstrate how ruthless the ethnically-generated verbal skirmishes can occasionally get. The epic poem that is Israel is still bedevilled by a kind of bristling intra-tribal anger. It is as if each and every ethnic group rages at another: for not being more like them, for having a different accent, for being condescending and patronising, for always griping, for being simultaneously elitist and whining, for having too many children, for having only one child, for not being Zionist enough, for criticising Zionism too much. It wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to state that Israeli society is made up of as many ethnicities as there are countries in the world. And this without even considering the other, non-Jewish, ethnic minorities in Israel. Such a teeming plurality of tastes, politics, cultural bearings, foods, histories, stories, music, philosophies, and ethos conjoined within one tiny plot of land is bound to raise tensions and frictions. And the self-respecting liberated Israelis do not keep mum about any of it. If God gave human beings a mind to think and a mouth to speak, then by Jove, speak they will!

Many Israeli authors have attempted with varying degrees of success to represent the edgy quality of Israeli pluralism. In this article I will focus on Sami Michael, the emblematic, ironic, unique, all-Israeli author of ‘Otherness’.

In Michael we observe the evolution of a genuinely post-Zionist awareness. Not the nihilist kind of post-Zionism favoured by radical ideologues like Ilan Pappe, but a genuine challenge to the remnants of that high handed cultural hegemony captured in Golda Meir’s cold displeasure with Jewish cultures that differ from hers, and in Zach’s injurious comments about the cultural inferiority of Mizrahi Jewry. Michael evolved in his self-perception from Iraqi Jewish communist writing in his native Arabic language to an Israeli Jewish Mizrahi liberal writing in an acquired ‘mother tongue’, Hebrew. Early on he realised that the melting pot was not working: there is a dominant Israeli culture and newcomers are expected to shed their previous identities. There are second and third generation Israelis whose parents had fled from Arab lands, and who, upon their arrival in the promised land languished for years in the Israeli refugee camps, (euphemistically called ‘ma’abarot’, literally, temporary camps) before being re-settled in peripheral ‘hoods’ and border towns, like Sderot, Netivot, and Dimona. For them, general historical awareness and accurate remembrance of their uprooting and subsequent ordeals have not been easily available.

For Sami Michael it was clear that there was a general failure in the collective consciousness to acknowledge the catastrophic trauma of the nearly total deracination of entire Jewish communities from Arab-Muslim countries during the early fifties of the 20th century. In its initially formative years, Israeli society exhibited too feeble a will to retain and assimilate Mizrahi experiences, efforts and travails into the substratum of Israeli national awareness and make it a constitutive part of its national narrative.

Sami Michael’s post-Zionism is not of the enraged, moralising, hand-wringing type that leads to rejection of it all. He understood these historical processes in the context in which they happened, as an organic component of the wretchedness of human condition, and the aftershocks of the collective national ‘We’ to find and define itself. Whatever else is expressed in the examples cited from Golda Meir and Natan Zach, there is no denying the honest bewilderment they reflect. No ill will is communicated in Zach’s snooty remarks but great egotistical vexation about the Other who is not at all like his own cherished and familiar ‘I’.

From his own unique perch in Israel’s society, Sami Michael produced fiction that is neither nostalgic for an idyllic exilic past that never was, in the ‘old country,’ nor sentimental about present actualities.

Biography

Born in 1926 and raised in Baghdad, the young Sami Michael joined the Iraqi Communist party. When a warrant for his arrest was issued in 1948, he fled to neighboring Iran. As the Iraqi court sentenced him to death in absentia, and with no other country willing to accept him at the time, he was forced to immigrate to Israel in 1949. He settled down in Haifa where he joined the Israeli Communist party, and was invited to work for an Arabic newspaper by Emil Habibi. Michael, the only Jew on the editorial board of al Ittihad and al Jaded (Arabic language newspapers of the Communist party), worked there for four years. He also wrote a weekly column under the pseudonym ‘Samir Mared’, fielding stories in the spirit of ‘socialist realism’, laced with irony and humor. In 1956, disillusioned with the policies of the USSR, he terminated his affiliation with the Communist party, and quit his work on both papers: ‘I left the party but not the ideals of socialism,’ he wrote. Michael worked as a hydrologist in the north of Israel for 25 years, completing his hydrology studies at the British Institute in London, before studying Psychology and Arabic Literature at the University of Haifa.

At the age of 45 Michael embarked upon the daunting project of mastering the Hebrew language. In 1974 he published his first novel in Hebrew. The title of the novel – Shavim ve-Shavim Yoter (‘Equal and More Equal’) – became a well-known locution depicting the struggles of Jews from Arab countries for egalitarian treatment. This book contributed to the profound and hypermutable discussion about the ethnic-socio-economic gaps in Israel has been going on to this day. Sami Michael has gone on to publish 11 novels and three non-fiction books focusing on cultural, political and social affairs in Israel, three plays and a children’s book.

For many years he described himself as not a Zionist, but a patriotic Israeli citizen, comfortable to identify himself as an Arab Jew and an Iraqi.

‘Here’ and ‘There’

Naama Azulay Leventhal, in her 2000 Master’s thesis and subsequent PhD Dissertation about Michael explored the problematic condition of Mizrahi authors. Immigrant authors, she suggests, are vexed by a duality of rootedness. There is a ‘There’, the landscape of the native country they had left and there is a ‘Here’ the new motherland in whose protective lap they long to nestle. This is even truer and more complicated for Mizrahi Jewish authors: they needed to detach from roots in the country that had brutally dislodged them, and then sprout roots in the soil of the new but emotionally-distant motherland. Immigrant authors of similar origin, generation and experiences as Sami Michael (like Eli Amir, Shimon Balas, Amnon Shamosh) encompass the ‘There’ and the ‘Here’ within the same novel. Distressing and bitter as the encounter with the patronising Ashkenazi culture is, these authors urge their fictional protagonists towards a process of transformation that will alter their identity and create a sense of belonging. They favour Freudian psychological accommodation in which the horrors of the Iraqi past are muted by nostalgia and the privations of the Israeli present are ultimately absolved.

Sami Michael opts for a different literary tactic. His protagonists do not oscillate between two worlds, in an attempt to adjust and perhaps become accepted. He does not trust the Melting Pot concept with its promise of becoming a ‘legitimate’ son of the land. Michael compels his characters to adhere to their Otherness, because ‘from the margins you can better see the centre. If we want to understand the essence of the centre, we need to look at the margins.’

Interestingly, Michael’s ironic vision and literary starkness are presaged in the works of an early pioneer in Hebrew Literature, Haim Yosef Brenner (member of the 1920’s Second Aliya). Brenner’s divergence from what Amos Oz refers to as the ‘ecstatic’ ‘genrist’ (from ‘genre’) view of the authors of early Hebrew Literature in Palestine echoes Michael’s shunning of an uplifting literature that paints an attractive Utopian scene. Like Brenner who wanted ‘the brutally depressing facts to speak for themselves, without any authorial intervention or literary heightening’ Michael prefers to write fiction that is self-exposing, breaks stereotypes, and depicts unheroic reality. About the romantic tradition of gilding the past he wrote: ‘those [authors] who glorify the past and douse it with perfume have not grasped the reality or dealt with it directly. Perhaps they heard about it from their parents or elderly persons who view this past through the rose-tinted glasses of memory, and perceived some impressions and smells; this leads to falsification and distortion. I present the past as I experienced it…’

Though the ‘Here’ and ‘There’ dichotomy is strongly present in his fiction, Michael assigns separate spaces to each place and its attendant reality. 20 years elapse between Michael’s arrival in Israel and his first novel Equal and More Equal in which he writes about the life of an Iraqi immigrant family in the Ma’abara. His second novel is about the life of a Jewish family in Baghdad on the eve of the Arab pogrom in June 1941 (The ‘Farhud’). In his third novel Refuge he is back in Israeli reality, on the eve of the Yom Kippur war. His fourth novel is about clandestine Communist and Zionist activism in Baghdad. His fifth novel tells of a Jewish-Arab love story during the first Lebanon war. Next he published a youth love story in Baghdad during the period that preceded the final displacement of Jews. In his 1996 novel Victoria he recounts the troubled life of a young illiterate Jewish woman in a strictly patriarchal milieu is ‘There’. In Pigeons at Trafalgar Square (2005) he returns to the ‘Here’, to tell about an abandoned Palestinian baby boy adopted by an Ashkenazi couple of Holocaust survivors. His last two novels, Aida 2008 and Flight of the Swans (2011) repeat the pattern of ‘Here’ and ‘There’. Aida’s unlikely protagonist is an elderly Jew who is a popular TV personality in Saddam’s Hussein’s Iraq. Flight of the Swans is back in Israel, with a love story centered in a carefully constructed community in Haifa, Michael’s city. (The editors are grateful to Prof. Michael Weingrad for alerting us to the omission from the list of his oeuvre of Sami Michael’s two most recent novels in an earlier version of this article.)

Equal and Worthy

The English translation of Shavim Ve-Shavim Yoter was Equal and More Equal but the title did not capture the polyphony of meanings implied in the original. ‘Shaveh’ means, primarily ‘equal’ but it is also colloquially used as ‘worthy of’, ‘deserving,’ and ‘admirable’. The titular wryness of ‘Equal and More Equal’ is impregnated by the secondary meaning. The irony of the title resides of course in the mathematical impossibility of being simultaneously equal and more equal and the human possibility of being worthy and more worthy.

The novel’s narrator is the adolescent David through whose eyes we experience the difficult immigration process that a respectable middle class family in Jewish Baghdad community underwent in Israel. The story begins as the family prepares to meet their new homeland:

We were all dressed in our best garments, tailor-made of expensive English wool and pure silk. Father stood next to mother, all regal omnipotence…’ but ‘no lovely hostesses were sent to greet us. Instead, a grey bunch of pasty-faced bureaucrats appeared… in five short minutes the new homeland turned my father from an energetic man in the prime of his life to an old broken abject fool… Before we got our bearings, a white cloud of white DDT powder enveloped [David’s father], formerly a distinguished member of the Baghdad community…

The disappointment and humiliation experienced in the first years in Israel do not diminish Michael’s condemnation of the Iraqi past: ‘In the diaspora, father was forced many times, especially during the final years, to forego his dignity, for the family, for his own life and for our survival … ‘ or this: ‘From the kitchen radio raucous shrieks blared. The new hit “We’ll burn you Tel Aviv” was repeatedly played. Violent mobs charged in the streets of Baghdad. Scariest of all was the sight of murderers, robbers, rapists and thieves who had been released from jails after they “volunteered” to fight against Israel. They stampeded in the streets on the way to the front, screaming: “Death to the Jews!”’

Michael, the ironic contrarian, refuses to suppress the horrors of Baghdad. Nor is he any more amenable to disregard the wretchedness of Mizrahi existence in the Israeli present. An Other in Iraq, and a different Other in Israel.

Becoming Israeli

Through his Otherness he eventually carved an identity for himself as an Israeli. This process of becoming, sidestepping any radical self-transformation, he managed in two phases. The first began with his arrival in Haifa where he joined the Israeli Communist Party and wrote for its Arabic language press. This phase ended when he quit the party in 1956, aghast at how little did the revelations about Stalin’s policy of persecuting Jews affect the party’s beliefs:

It was increasingly difficult to consider them the equal of Marx and Engels. In vain did I look for the in-depth analyses … the beautiful thinking of Maxim Gorky. I thought to myself where have they disappeared into, the great communists, great intellectuals, Howard Fast and others. Are these clowns now leading the communist party? … Once a week Tawfik Toubi would come to give us political instruction. I was stunned by the shallowness of the thinking that he brought with him. With his pile of clichés, he was trusted to cultivate our thinking …

In a speech at a conference in Haifa in June 2012, Michael revealed his enduring disenchantment with the Left:

The Parlour leftists – and in Israel, it is worth noting, the leftists have never left the parlour – repudiated Mizrahi Jewry as expendable ‘raw material’, or in the Communist jargon of that time: the ‘lumpen-proletariat’. This was in spite of the fact that immigrants from Egypt, Lebanon and Bulgaria, and especially from Iraq, held an impressive Communist record from their countries of origin. The Communist establishment in Israel treated these immigrants with manifest arrogance. At the beginning of the 1950s, 20 percent of the ma’abarot dwellers voted for the Communist Party in the Knesset. Not one of them was promoted to a position of any value in the party. The central committee of the Communist Party was and still remains today more ‘purified’ of Mizrahi Jews than any other establishment in the state. The suspicion and arrogance towards the Mizrahi communities formed a solid impenetrable barrier in the ranks of the Communist Party.

Leaving the small but cosy enclave of the Communist Party meant discarding his identity as an Arab-Jew Party member. It was a rite of passage of sorts: he was now confronted with the challenge of joining Jewish-Israeli life. A pivotal moment in his life was the birth of his first child ‘… I will wander no more. This will be my land…’ he thought, as he left the hospital with the newborn baby in his arms.

In the second phase of his ‘becoming’ he set out to fashion for himself a belonging that would not entail submission to cultural norms. For 15 years he put aside his literary ambitions, mostly because the only language he felt he could write in was Arabic and he wanted to write in the language of the land and to reach Hebrew readers: ‘… I live in an Israeli reality in which the language forms an integral part. People speak, think, dream in Hebrew. I cannot write about them in Arabic.’ Writing was a way of proclaiming his existence, a kind of active rebellion. At the end of those 15 years he published Equal and More Equal.

Refuge

Refuge, Sami Michael’s third novel published in 1977, examines the Israeli political margin – the Communist Party. Within this small self-contained community of like-minded people, some of the country’s most urgent conflicts still play out. The novel covers the first four days of the Yom Kippur war, from Friday 5 October 1973 till Monday night, 8 October. The main characters are Shula, an Ashkenazi, married to Marduch, an Iraqi Jew. They have a mentally-challenged little boy, Edo. Shoshana, Edo’s nanny, is married to Fuad, a Muslim Arab, who runs an Arabic paper for the Communist Party. The group is a kind of fraternity, close knit and bound by ideology and loyalty to a cause.

Marduch is nominally a Communist but also a patriotic Israeli. His scepticism is revealed in the fact that on his shelves there are books censured by the party leadership. He willingly joins his army unit at the start of the war. When his wife questions his willingness to fight for a country he so disapproves of he explains that the state of Israel took him in, gave him refuge, when he was hunted, tortured and nearly executed by the Iraqis. He owes Israel a debt because refuge is a supreme value in Oriental ethos. When the party instructs Shula to provide shelter, refuge, for the Arab poet Fathi who is sought by Israeli police because he is considered a security risk, she immediately obeys, out of deference to her husband’s time-honoured values.

Shula’s mother who pays for Shoshana’s services, is also a member of the Party. She had in the past contrived her daughter’s marriage with Marduch. Shula’s true love, a military officer was not a member of the Communist party and therefore unacceptable. The mother, fearing Shula might marry an Arab, encouraged the marriage with Marduch despite his Mizrahi origin. It was, for her, the lesser of two evils.

In the first two chapters, the author sets up this perfect storm of conflicting loyalties, politics, myths, and interests. The irony is gently interwoven into the straggling narrative lines, as party comradeship rapidly comes unglued: Shula and Marduch believe that if Israel is defeated, it will mean a second Holocaust. Fathi the poet (and the darling of Tel Aviv parlours), hopes for an Israeli defeat, even as he shelters under Marduch’s roof and tries to seduce his wife. Shula’s mother is revealed as a sham communist. Shoshana, married to an Arab, is alienated from her beloved family, not accepted by her husband’s friends and family and worries that her second son is radicalised while her eldest son wants to be an Israeli Jew.

The ironies are scattered every which way. While the events move fast and hang like doom over each of the featured characters, the reader is lulled into a kind of stupor by the understated, nearly hushed tones of the novel. No sirens in the background alert us to the raging war but a kindly neighbour who comes to Shula’s apartment to hang blackout sheets over the windows.

Irony

Irony, Michael’s chosen trope for his writing, accords with his belief that it was ‘from the margins you can better see the centre’. Immanuel Levinas considers the self and the Other as always in a dynamic relationship. If the self is the centre, the Other is the margins. In Michael’s Israeli novels, it is a given that Ashkenazi culture occupies the centre, is the assumed ‘self’ of society. As a Mizrahi immigrant-author, Michael balks at being subsumed into that centre. By refusing to be bribed, seduced or chastened into abandoning his intrinsic centre, for which that cultural hegemony is the margins, he never relaxes his ironic gaze upon the unfolding events. His inner awareness of himself as a perpetual but resilient Other is thus closely related to the ironic mode of his fiction.

The story of Sami Michael with its many life ironies says much about the country that had received him and other immigrants with such churlishness. This imperfect country forgave him without reserve for refusing to be integrated into it, enabled him to acquire the tools and provided him with platforms from which to chastise it to his heart’s content, praised him for his outstanding literary achievements, nodded meekly at his pessimistic glower, and treated his robust and authentic Otherness as a source of national pride. These relational configurations between Author and Society, Centre and Margins, Self and Other are always in a flux, thus purveying the supreme irony: Sami Michael is the definitive all-Israeli author.

“‘Some of the leaders in this protest movement are just pissed off because their grandmother did not leave them an apartment in Basel.”

The perplexing reference to “Basel” in this quote is not Basel, Switzerland but rather Basel st., Tel Aviv:

Basel is where Tel Aviv’s yuppies go to get the espressos, young mothers go out for a walk with their strollers, and in-the-know women come to get their designer and alternative clothing. It’s clean and chic the locals love it.

Basel is actually a 650 meter long street that connects Ibn Gabirol to Dizengoff, but when talking about Basel, Tel Avivians always refer to the even shorter part between Yehoshua Bin Nun in the east and Sokolov in the west, and the surrounding little streets. It’s right in the heart of the Old North, but it’s so nice we decided to give it its own section.

Around the Basel square, whose official name is the City’s Builders’ Square, is where it’s all happening. The attractions are conveniently located around it and everything you want to check out is within a 1km radius. It’s more of a hangout/shopping area than anything else, and if you get here on Friday or Saturday late morning or early afternoon you’ll have trouble locating a spare chair to sit on, as it seems everyone and their sister is here.

Basel Street is named after the Swiss city, where Jews held their first Zionist Congress in 1897, after which Theodore Herzl, otherwise known as The Visionary of the State of Israel, famously declared: “In Basel I establish the Jews’ State”.

http://www.cityguide.co.il/tel-aviv-areas/north/basel-area/