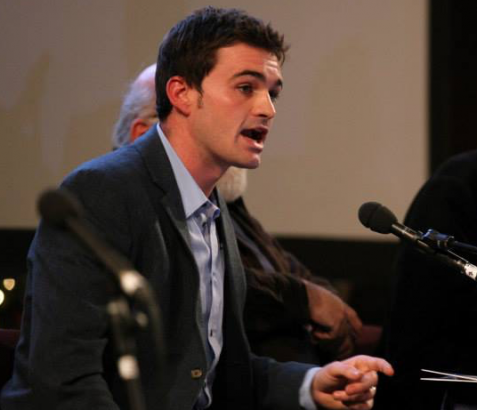

John Lyndon is Executive Director of the Alliance for Middle East Peace (ALLMEP). He argues that the Trump Plan is neither part of the peace process nor the latest iteration of the two state solution, but rather has been designed to bury both and move towards a new paradigm: annexation.

Shalom. Salaam. Peace. These words, famously—to the point of cliché—are used millions of times every day as terms of greeting and friendship by Arabs and Jews. That’s one of the reasons why it has been disappointing to observe the delegitimisation of the term in Israeli and Palestinian political discourse over the last generation. However, in Washington last Tuesday, the word ‘peace’ —used 42 times by president Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu over the course of a deeply disingenuous hour—was finally emptied of all meaning.

In a room which Chemi Shalev likened to a ‘ZOA Gala Dinner’, assembled a who’s-who of the pro-Israel right-wing and evangelical movement, a heavy press contingent from Israel, several prominent Republican donors, three GCC ambassadors, and… no Palestinians.

Reading through the plan that evening, it was immediately clear that it was unlikely to result in ‘peace’ between Israelis and the Palestinians who watched on television 10,000km away as the fate of their lands and lives was determined by others. It might seem basic, but it is worth reminding ourselves what that word ‘peace’ means. It requires both parties agreeing to put conflict behind them and enter into a mutual agreement predicated on the absence of hostility and violence and ending their respective claims. It requires parents telling their children: ‘it’s over,’ and each party feeling sufficiently satisfied with any compromise so as not to allow the past to continue to dictate the future. We used to understand that. I’m not sure precisely when it happened, but at some point the entire ‘peace process’ became strangely unmoored from that concept.

The Palestinian leadership is ripe for criticism and deserving of plenty of blame in any fair accounting of how we have arrived at this nadir. President Abbas should reflect long and hard on his failure to respond to Ehud Olmert’s offer in 2008, as well as his role in the collapse of the 2014 Kerry talks, and on the fact that the Palestinian people have not had a chance to democratically evaluate his performance for fifteen years. However, it is a simple statement of political fact that the details that this plan sketches out on Jerusalem, borders and refugees fall well below the minimum that any Palestinian leader could accept and sell to their people. That each issue was shrouded in language obscuring its true content, designed as Orwell explained in Politics and the English Language, to make ‘lies sound truthful,’ was initially jarring:

* A ‘two-state solution’ but with a Palestinian ‘state’ on less than 70 per cent of the West Bank, broken up into three isolated islands within an archipelago surrounded on all sides by Israel, with Israeli settlements remaining both within and around them, under permanent occupation, and deprived of almost all of the basic characteristics of sovereignty. Even this heavily circumscribed promise of statehood is only within reach for the Palestinians if they fulfil a plethora of obligations that few other states in the region would be able to meet.

* A capital in ‘Eastern Jerusalem’, which was made clear meant Abu Dis, Kufr Aqb and Shuafat refugee camp, parts of the city that were not considered part of Jerusalem at any point in Palestinian history, with no control over holy sites, and a ‘special tourist zone’ in the dystopian wasteland around the Qalandiya checkpoint.

* A ‘settlement freeze’ in areas set aside for the Palestinian state for four years, but Netanyahu clarified later that this only applied to areas where there were in fact no settlements, with Israel free to annex the remaining parts of the West Bank unilaterally, and so undermining the very point of such a freeze which is to maintain the territorial viability of a Palestinian state.

Only on refugees was there no shrouding. Their status, and UNRWA, the body set up to address their needs, would be dissolved, and their ability to return to the Palestinian ‘state’ envisioned in the plan would be heavily circumscribed, with any discussion of limited return to their ancestral lands in what is now Israel completely off the table.

Perhaps most basically, ending the occupation that began almost 53 years ago is—for literally every Palestinian I have ever met—the most fundamental indictor that we have reached peace. Indeed, the justification of Israel’s military occupation is that it is a function of the protracted conflict. If this document promises ‘peace’ then why is permanent occupation at its very core?

There is absolutely no chance that the Israelis and Americans who drafted this plan expected the Palestinians to accept it. So, if the plan cannot credibly be claimed to be the basis of a peace deal between Israelis and Palestinians, it is fair to ask: what is its utility? Certainly, it has political advantages for the beleaguered US and Israeli leaders both up for re-election.

Yet there is also another logic fuelling this whole enterprise: slightly less cynical, immeasurably more ideological, and clearly signalled by figures such as the US Ambassador to Israel, David Friedman. That logic—now shared by most of the Israeli right, and at least rhetorically by many in the centre—is one of annexation. If you boil the plan down to its most basic parts and bake in Palestinian rejection as a given, what remains is a flashing green light for Israel to annex a third of the West Bank. This is the message Ambassador Friedman gave soon after its release, ‘If they wish to apply Israeli law to those areas allocated to Israel, we will recognise it.’

I know of no single Palestinian—and the nature of my work means that I know some of the most moderate and compromise-minded Palestinians alive—who is willing to accept this deal. Equally, I do not often meet Palestinians under the age of thirty who are enthusiastic supporters of an actual two-state solution. This plan has undoubtedly sped up the death—which will be conclusive should Israel annex swathes of the West Bank—of the hundred-year debate about partition. Its conceit is that Palestinians will accept living in militarily occupied Bantustans as an alternative. They will not, almost certainly demanding equal rights in the state that controls their lives.

While much of the deception in this plan is so transparent as to be revealed on first reading, its greatest deceit is more deeply buried. This plan is the most anti-Israel proposal ever endorsed by a US President. By humiliating the Palestinians, it guarantees continued conflict and insecurity for Israelis. In discrediting the role of the US as the sole mediator, it makes any future negotiations—if we’re lucky enough to see them— much more likely to be internationalised or led by parties less sympathetic to Israel. In generating rejection by some of the most pro-Israel Democrats in Congress, it makes Israel a partisan issue in a way unimaginable just a few years ago. By shockingly suggesting that the citizenship of Israeli-Arabs was up for discussion, it tears an already fraying part of Israel’s democratic fabric. And by burying the two-state solution it hastens the arrival of a reality where Israel will either need to sacrifice its democracy or its Jewish majority.

So what to do? First: we must rehabilitate the pursuit of actual peace, from the bottom-up. We have a generation of Israelis and Palestinians now entering young adulthood who are more physically separated and politically polarised than any other since the conflict began. We must disrupt this. Encounters between Israelis and Palestinians must be exponentially scaled so that the basic empathy, respect and mutual recognition required for peace and utterly absent in this document is re-built.

The international community, which has entirely failed to deliver on the promises made in the 1990s, has a moral obligation to radically increase their support for such efforts. I and other committed supporters of a two-state solution must also recognise that the chances of it ever arriving are now too low for us not to have a contingency plan. Luckily, the societal conditions for a just two-state solution and an ethically defensible alternative are exactly the same. If we had ten thousand times as many daily encounters between Israelis and Palestinians as we have now, I am certain that it would produce immeasurably better ideas on how Israelis and Palestinians can share or divide this land than are to be found within the 181 pages of this plan.

The past week has been difficult for anyone committed to real peace between Israelis and Palestinians. But perhaps it can also provide some sobering clarity. The period that began with handshakes on the White House lawn in 1993 is over. The Trump Administration has offered us a highly detailed blueprint of its idea of what should come next. If we—the Israelis, Palestinians and internationals committed to a just peace— want a different reality, let’s stop reacting, start acting, and set about building it.

A plan that calls to “rehabilitate the pursuit of actual peace, from the bottom-up” that doesn’t include changing the Palestinian education system to remove Jew-hate and suicide-massacre from the curriculum, and ending Palestinian pay-for-slay, which is more than 7% of their economy, is not only delusional but deceitful.

Fix that before you start arranging “encounters” because there is certainly no chance of peace while that continues.