Gerald M. Steinberg, Bar Ilan University and Ziv Rubinovitz, Sonoma State University are the authors of Menachem Begin and the Israel-Egypt Peace Process: Between Ideology and Political Realism (Indiana University Press, 2019), based on newly released Israeli documentation of the negotiations that led to the 1979 Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty. The documents, they claim, cast a new light on the actions of Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, a man framed by US President Jimmy Carter as a ‘reluctant peacemaker’.

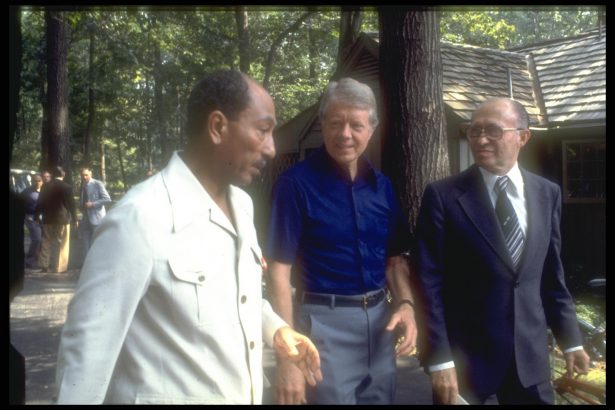

The Israeli-Egyptian peace agreement of 1979 remains a unique accomplishment, not only in the otherwise bleak landscape of the Middle East, but throughout the world. Forty years after the leaders of Israel and Egypt, with the support of the US, signed the treaty, its terms continues to serve as the basis for stability and cooperation between the two nations. Prime Minister Menachem Begin and President Anwar Sadat achieved what many thought was impossible. Building on limited disengagement agreements following the 1973 Yom Kippur war, they overcame mutual suspicions and internal opposition.

In order to learn and build on the lessons from this successful example of international conflict resolution, it is important to examine and understand the details, and to distinguish between the record, as reflected in the available documentation, and the less substantiated and second-hand accounts.

In particular, the recent release of official Israeli documents, including transcripts of meetings during the Camp David summit of September 1978, as well as official diplomatic cables, and the internal assessments made throughout the process provide important new insights. Through these documents we can gain a much sharper understanding of, and insight into, the perspectives and considerations of Begin, who, in contrast to other central actors – Americans, other Israelis, and, to a lesser extent, Egyptians – did not publish a memoir or provide extensive interviews.

On many of the key issues, the Israeli documents reinforce the existing analysis. The background of the very costly 1973 Yom Kippur war, which ended with a ‘mutually hurting stalemate,’ triggered the search for a solution which would meet the core interests of Egypt and Israel, and prevent another and probably more destructive round of warfare. The two limited disengagement agreements in 1974 and 1975 were also important confidence-building measures, and were followed by various signals from Sadat to Israeli leaders regarding additional steps.

The Israeli elections that took place in May 1977, and the political ‘earthquake’ in which the Likud took power, headed by Begin, was a major turning point. As the documents illustrate, from his first day in office, Begin gave the highest priority to the possibility of reaching a peace agreement with Egypt. He immediately familiarised himself with the issues, and understood that Sadat sought to recover the Sinai Peninsula, and Egyptian pride, both lost in the 1967 Six-Day War, but without risking another war. His decision to appoint Moshe Dayan as foreign minister, despite Dayan’s membership in opposing political parties, was also closely linked to this objective.

Indeed, Begin’s words and actions throughout the process highlight the emphasis he placed on reaching an agreement, in sharp contrast to the distorted images in some of the existing analyses, particularly from US President Jimmy Carter, that portray the Israeli prime minister as a ‘reluctant peacemaker’, a ‘right-wing ideologue’ or, after the Camp David accords, as having ‘buyers’ remorse’, as Ambassador Sam Lewis suggested. A number of these distortions are repeated by Carter’s Middle East advisor, William Quandt in his recent article in the Cairo Review of Global Affairs, (‘Reflections on Camp David at 40’, December 2018).

Similarly, the previous accounts generally ignored the complexities of Israeli politics and, like many American officials, mistakenly viewed Begin as if he held a position equivalent to the US president, rather than as the leader of a fragile coalition often under attack from his core constituents. The Israeli documentation allows for a more robust analysis, based on two-dimensional negotiation models – the external realm and the internal one. For some of Begin’s long-time supporters in Herut, his willingness to remove the settlements in the Sinai and agree to even a minimal form of autonomy in the West Bank was treasonous, and a number of ministers resigned in protest. This criticism was shared by hawkish members of the Labour opposition, increasing the political pressure on Begin, who, it should be recalled, had taken office only one year earlier. Pressures from Carter and Sadat for more concessions, particularly on the Palestinian issue, were domestically untenable.

In tracing the evolution of Begin’s efforts to reconcile the opposing pulls of ideology and political realism, his stint as a member of the National Unity Government created just prior to the June 1967 war provides important milestones. After the ceasefire, the cabinet, led by Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, endorsed the land-for-peace formula for Egypt and Syria, and Begin – based on his understanding of political realism and the Israeli national interest – joined in approving this framework. He repeated this position on numerous occasions, emphasising the importance of a full treaty, as distinct from partial agreements such as non-belligerency, which, he argued, would not bring Israel the full legitimacy that was required. In 1970, Begin resigned from the cabinet and returned to lead the opposition, citing the government’s acceptance of the Rogers Plan, which ended the War of Attrition and included UN Security Resolution 242 as the basis for further negotiations.

Seven years later, as Prime Minister, Begin embraced the opportunity to implement his policies, starting with briefings on the details of Sadat’s visit to Romania. After Begin went to Washington to meet President Carter to discuss peace options (the meeting summaries reflect major disagreements), Begin traveled to Romania, and, in parallel, sent Mossad head Yitzhak Hofi to Morocco (later, joined by Dayan) for secret meetings with one of Sadat’s closest aides, Hassan Tuhami.

In the midst of these activities, the US was working on a parallel track based on the Geneva conference concept, expanding on the stillborn framework that Henry Kissinger tried in December 1973. In many of the analyses of the peace process that were published previously, and particularly in the American versions, the catalysing impact of the push towards Geneva on Begin and Sadat is omitted. In particular, Carter’s effort to involve the Soviet Union alienated both leaders, who made common cause in going around Carter. Sadat had recently evicted the Soviet military from Egypt, and Begin’s experience as a prisoner in the Gulag left a lifelong hostility – both viewed Moscow’s potential role as entirely anathema. The two leaders were also concerned that the American effort to solve the entire Middle East conflict, which included bringing in Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and Syrian President Hafez Assad, as outlined in a plan published by the Brookings Institution, would fail and also prevent realisation of a bilateral peace agreement.

Based on these shared interests, Sadat made a number of public statements referring to a potential visit to Israel, and Begin used back channels, including through US embassies in Tel Aviv and Cairo, to send positive replies. These events set the stage for Sadat’s dramatic Saturday night arrival in Tel Aviv in November 1977, which set the formal public process in motion. For Israelis, the appearance of the Egyptian leader sent a powerful signal of acceptance, and created the expectation that a peace agreement was possible.

After the euphoria of the initial visit, however, the negotiation of the detailed terms turned out, not surprisingly, to be slow and difficult. Two sets of issues were simultaneously on the table. First came the terms of the Egyptian-Israeli peace, such as borders, the fate of the settlements in Sinai, and security arrangements. To help resolve the complexities and provide security as well as financial guarantees, it was necessary to bring Carter and the Americans back into the negotiations, as seen at the pivotal Camp David Summit in September 1978.

The summit ended in success, with agreement on many of the core issues, but regarding the process, much of what has been written needs revising in the wake of the Israeli documents. While Carter and the Americans emphasised psychological dimensions, describing Begin as a stubborn and legalistic quibbler, and Sadat as temperamental and prone to sweeping generalities, and separated them after the third day, these were largely irrelevant. Instead, the concentrated negotiations that took place during this two-week period focused largely on interests and trade-offs. The Egyptians agreed to the Israeli demands for demilitarisation, a monitoring framework for the Sinai, and a full peace treaty, including the exchange of ambassadors, as well as transport lines, and cultural, touristic, and academic exchanges.

In return, Begin acceded to the removal of the Israeli presence – military as well as civilian – from the Sinai, becoming the first leader in the history of Israel and Zionism to take down settlements. His closest friends and allies were livid, calling him a traitor, which was very painful, and required Begin to use significant political resources in order to stem the revolt.

But as a realist, the Israeli leader recognised the core Israeli interest in a peace treaty with Egypt, and to reach this goal, he would have to pay the cost. He understood that there was no alternative – Sadat was not going to accept anything less than a full Israeli withdrawal in exchange for a full peace agreement. This was the Egyptian position from the first talks between Dayan and Tuhami in Morocco, and Begin had enough time to prepare, once Sadat accepted Begin’s core security and diplomatic requirements.

The second and more complex dimension involved the Palestinians and the future of the West Bank. During the second week of Camp David, and much of the ensuing six months until the signing of the treaty, talks focused on these issues. Sadat, and to a greater degree Carter, demanded that the Egyptian-Israel treaty be linked to an agreement on the West Bank. Carter continued to press for the ‘Palestinian homeland’ that laid at the core of the Brookings Institute plan, and sought to force Begin to expand his limited autonomy plan so that it would lead to this result.

This is where Begin’s ideological commitment was not flexible, and he repeatedly told Carter, as well as his Israeli constituents, that no foreign sovereignty in any part of Eretz Israel would be acceptable. For the sake of peace, he accepted the need for Palestinian self-rule on domestic issues, while leaving Israel responsible for security and foreign policy. During and after Camp David, Sadat acquiesced to the limits that Begin presented regarding the West Bank, but Carter maintained and even increased the pressure. The challenge for Begin was to avoid a total rift with the president of the US, despite threats to blame Israel for the failure of the peace effort. In their intense meeting on the last night of the Camp David talks, Carter insisted that Begin agree to a long freeze on settlement construction on the West Bank – a demand that the US had made repeatedly and which Begin repeatedly rejected. According to Carter, this time, Begin agreed and promised to provide a letter in the morning to verify a five-year moratorium. When Begin’s letter referred to three months (until the expected signing of the peace treaty with Egypt), Carter was livid and accused Begin of backtracking. However, the Israeli notes from this meeting (there is no American summary) as well as later a Senate testimony from Secretary of State Vance corroborate Begin’s version.

It took six months after Camp David to turn the accords into a treaty, in part due to Carter’s ongoing effort to force Begin to change his policies over the West Bank, but the terms were finally agreed and signed on 26 March 1979. This was a stellar achievement for which all three leaders deserve credit, and counter to pessimistic predictions of many Israelis, the agreement has withstood numerous crises.

Lessons to be learned

Moving forward, not only in the Middle East but also in attempting to apply the lessons to other protracted international conflict, an accurate examination of the negotiation record is essential. Success requires leaders who see peace as a national priority and are willing to take prudent risks in order to achieve this objective. Such leaders and the interests that they share cannot be produced artificially or through outside pressure, and in their absence, efforts to reach agreements have no chance. In Sadat, Begin had a partner who recognised this, and vice versa, and on this basis, they explored the possibilities for agreement.

Once these starting conditions are in place, third parties and mediators can provide vital support, but they must avoid piling on additional demands beyond what the core actors and their political support systems are able to accept. It is important to assess the domestic political constraints of each of the parties, and work within those constraints in order to facilitate an agreement. This rare instance of successful international negotiations demonstrated the importance of staying within the boundaries of political realism. Thus, while the US imagined the benefits of a comprehensive agreement involving the Palestine Liberation Organisation and the Syria regime, Begin and Sadat recognised the obstacles that that would create with respect to the bilateral process. Begin’s position on the Palestinians was anchored in immovable ideology, and not due to a ‘recalcitrant personality’ or other psychological factors.

Finally, with the addition of the perspectives provided by the Israeli documents, and, in particular, Begin’s careful management of the Israeli negotiating position, it is possible to better understand the factors that led to the successful outcome. For those who hope to follow Begin and Sadat, or for third parties that seek to bring other leaders of countries involved in violent conflicts to the negotiating table, it is necessary to examine the interests, benefits and potential risks from the perspectives of all the actors. After 40 years, the Israeli dimension of these complex events can now be analysed in detail.