This has got to be the most surprising, and thrilling, of all trends to have ever emerged in Israeli cinema: the rise of the horror film. Six have been produced in the last two years; in the previous 65 years, the number was zero. It’s a revolution.

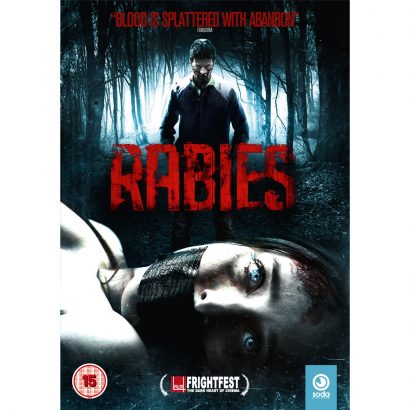

Spearheading this trend are Aharon Keshales and Nevot Papushado, who directed Israel’s first horror film, the almost entirely independently-financed Rabies (2011). Slasher tropes were blended together to create a film that is at once suspenseful and something of a parody of the genre. Rabies tells us a few things about what is happening in Israeli cinema.

First, the fact that Israel’s biggest film and television stars agreed to participate in the movie for minimum wage so they could be killed on camera not only made the movie noticeable in Israeli mainstream media, but also tells us that many of the younger generation in the Israeli film industry are thirsting for an alternative to the standard Israeli story-lines of the family drama, the political drama, and the war film.

Second, while Israeli movies are often exiled to the art-house crowd, Rabies crossed-over to a younger generation of international viewers, taking the genre festivals by storm and being critically acclaimed among film bloggers around the world; some of whom noticed Israeli cinema for the first time.

In Israel the second movie is the hardest to make, the one that can kill a career, but Keshales and Papushado looked the Second Feature Syndrome square in the eyes and put a bullet between them with their follow-up. Big Bad Wolves had its UK premiere in August, to rave reviews, as the closing night event of Channel 4’s FrightFest. A violent revenge thriller with sinister undertones and a pitch-black sense of humor, Big Bad Wolves is an amalgam of fairy tales and folk stories – Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Little Pigs, Snow White, and Peter and the Wolf come to mind – shot and directed in the style of the masterpieces that made Korea into a horror Mecca a decade ago. But the story is universal: an off-the-rocks cop and a grieving dad kidnap a nebbishy school-teacher they believe is a maniac child rapist and killer. They tie him up in a basement and start torturing him until he confesses his crimes and reveals the whereabouts of his latest victim. It is not too long before we realise: he may very well be the killer, but he’s not the psychopath in this cellar. Not by a long shot.

Third, that Big Bad Wolves is first and foremost a ‘Movie Movie’ – a film which trades mostly in truths found in other movies, rather than in real life – signals another new development in Israeli cinema. Some American critics missed this, reading Big Bad Wolves as a political metaphor about the excessive use of violence in Israeli society. It seems that no matter how hard Israeli filmmakers try to make escapist box office hits, off-shore reviewers will always strain to link the movie to a political reality they are familiar with. In this case, that is a critical failing, for the ‘statement’ the film makes surely relates to film itself. At one level Big Bad Wolves is a pastiche of American, English and Asian revenge thrillers and torture-porn slasher movies. At another level it uses those very movie cliches to explore the ways in which we see violence in our mega-visual culture. In the movies, we believe that police violence is necessary to capture villains, whereas in real life police violence will enrage us; in movies we root for the vigilante, while in real life we oppose those who take the law into their own hand and bypass the judicial system; in movies we sneer at the murderous villain.

Big Bad Wolves subverts all these categories. The cop and the vigilante are the psychopaths, the pedophile is the victim, the good hunter is a deranged pyromaniac and the knight on a white horse is an Arab. The film’s challenge: How does the viewer empathise now? Big Bad Wolves is a smart movie that teaches us not to trust the things that movies teach us.

And there is more. Eitan Gafni’s Cannon Fodder, Israel’s first zombie movie, is currently making the rounds at genre festivals – like Rabies it is an independently produced affair dreamed up in the halls of Tel Aviv University Film School. Meanwhile, at the Jerusalem Film School a trio of graduates hatched up Cats on a Paddle Boat a Troma-influenced trash-horror movie played for laughs. More horror films, such as the apocalyptic Another World, which promises to be Israel’s first ever 3D movie, are nearing completion.

The rise of Israeli horror tells us about one more change in Israeli cinema. While the older film scholars taught us that Israelis cannot make genre movies – the day-to-day life of the ordinary civilian is so ripe with existential tension that genre movies seem fake, they argued – a younger group of directors, who have escaped real-life and found solace in American movies, are starting to say the opposite: real-life in Israel is so intense – this column is being written as the clock is ticking towards an American attack on Syria, that may lead to a Syrian missile attack on Tel Aviv, where I live with my wife and kids – that making Genre Films that are violent, brutal and extreme, where the innocent suffer first, is an authentic aesthetic response.