Editorial Introduction to the Symposium: In this symposium, six experts – Kyle Orton, Aymenn al-Tamimi, Craig Whiteside, David Wells, Michael Barak and Ely Karmon – discuss the prospects for reconstruction and governance in formerly ISIS-held territory after the immediate military victory of the coalition forces. What is the balance sheet on the coalition’s campaign? What is the likely future of the Jihadi movement? How should the West deal with the ‘returning Jihadis? And what is the shape of any viable regional security framework.

*

Craig Whiteside examines how counterinsurgency tactics currently being used by the Iraqi government’s security forces – such as population expulsions, extrajudicial killings, and mass incarceration – could influence the future rise of another ‘Islamic State’ organisation. This was originally published on the 18 July 2017.

This essay builds on Kyle Orton’s recent article for the symposium, which comprehensively lays out the political, social, and military conditions that will determine whether the Islamic State (IS) will survive the current efforts to defeat it in Syria and Iraq. I want to focus on some of the interesting aspects of post-IS governance and security in recently liberated areas of Iraq. Certainly, our understanding of a ‘post-IS’ future is a clearer in Iraq than in Syria due to the steady progress of the allied coalition campaign.

The Iraqi government, which under Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has significantly more perceived legitimacy among the native population than its Syrian neighbours, has worked hard to re-establish its sovereignty over its lost territory. It has also benefited from the fact that compared to Syria – where there is a surfeit of actors competing to be the legitimate government of various areas – Abadi’s administration is politically unchallenged, at least until the next elections. This democratic norm is a boon for Iraq and a reason for optimism for the chances for IS’s demise in the country.

The Abadi administration should be recognised for the tremendous momentum it has developed since the dark days of the summer of 2014. But before we celebrate prematurely, it must be pointed out that there are some troubling indicators that efforts to stamp out IS in Iraq, while effective in the short term, might give the movement a lifeline to survive well into the future.

This article focuses on three problematic and underreported counterinsurgency tactics executed by the government’s various security forces: population expulsions, extrajudicial killings, and mass incarceration.

They make a desert and call it peace

The media attention directed at the large urban military campaigns has allowed government actions in more rural areas to go unexamined. This is short-sighted because these areas are an important factor in preventing a return of IS. After the loss of territory to IS in 2014, the Iraqi political establishment has approved more drastic security measures for at least two former IS strongholds that dominate strategic locations: Tal Afar (near Mosul) and Jurf ah Sakhr (south of Baghdad).

According to Joel Wing, in early June 2017 the population in the towns of western Nineveh were forced to leave by Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU) and sent to displacement camps as part of clearance operations outside of Mosul. This displacement may be a temporary measure, but there is a good chance the security forces have other ideas. The rural areas of Mosul have produced more than their share of IS luminaries, including deceased military commander Abu Muslim al-Turkmani and political/religious leader Abu Ali al-Anbari – who are both from Tal Afar – and establishing government control over this hotbed of IS support is a key military concern. This area has also been the most popular route for foreign fighters into Iraq from Syria, as documented in the famous Sinjar records of 2006. Permanent physical control of the area could mitigate any future suicide bombing campaign targeting Baghdad, much like the one waged by the Islamic State of Iraq, IS’s predecessor, in 2010 that helped keep the ideological and sectarian fires burning. Lastly, this area is strategically important for those elements in Iraq’s paramilitary forces which are beholden to Iran due to Iranian interest in cross-border cooperation with its militias in Syria. Some are calling this the ‘land-bridge’ between Syria and Iran.

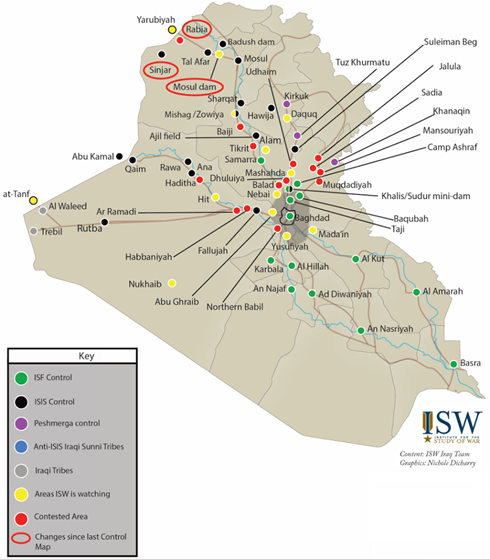

This August 2014 map from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) shows contested areas in red and IS controlled areas in Black. Tal Afar and Jurf ah Sakhr (Northern Babil) have been historically influenced by the Islamic State movement in its various forms, and both areas are focal points for the government today.

If this deliberate population displacement sounds fantastical, consider the fate of Jurf ah Sakhr. The rural town along the Euphrates River was the de facto capital of the Islamic State’s southern governorate (wilayet) during 2013 and the scene of tremendous conflict before the fall of Mosul in 2014. Government efforts to retake this part of northern Babil province were successful in late 2014, and the district’s population (120,000) was evacuated at the time for safety reasons. To date, authorities have not allowed them to return. One obvious reason for the permanence of the population displacement is Jurf’s location, which sits within a few miles of the most popular pilgrimage route in Iraq, which runs from Baghdad to Karbala and Najaf Shia shrines. The biannual pilgrimages (Ashura and Arba’een) attract up to 20m visitors, and inspired a perennial Islamic State bombing campaign that dates back to 2004. The political impetus to end the violence against the pilgrims is the most likely reason that Sunnis no longer live in Jurf ah Sakhr. Advocates’ efforts to resolve this issue have been a failure, but the message that it sends to Sunnis is very clear. (Author’s note: Jurf ah Sakhr [rocky bank] is now called Jurf al Nasr [victory bank] after the provincial government [dominated by Shia Iraqis in nearby Hillah] renamed the district post-liberation. This begs the question whether the involuntary name change also refers to the defeat of the local population by its own government.)

Rough justice and bodies in the desert

If the population displacement happens below the radar, summary executions of suspected IS members have been more visible, thanks to the work of Human Rights Watch and the news media which has reported on these extrajudicial killings during the Mosul campaign over the past six months. Not unlike the American military’s failure to plan for detention operations after the 2003 invasion – a series of errors that led to the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal – the Iraqi military seems to be untrained and unprepared to deal with the difficult task of separating Sunni civilians from IS soldiers, ‘caliphate’ officials, supporters, and family members. In the complexity and chaos, and in an environment estranged from the rule of law, Iraqi soldiers and militia members have taken matters into their own hands and executed prisoners on dozens, maybe hundreds of occasions. As documented by Anand Gopal’s reporting on the fate of Sunnis caught between IS and armed local militias, even refugees far from the fighting are not safe.

If the conventional wisdom holds that sectarian behaviour of government affiliated forces in Sunni majority areas assisted IS’s rise to power before 2014, what will the public knowledge of these widely reported crimes do to public perceptions of the legitimacy of an Iraqi government responsible for the security of all of its citizens and dedicated to supporting the rule of law? The Islamic State’s propaganda narrative for over ten years has capitalised on Sunni estrangement and disenfranchisement, and the abuse of Sunnis has been a rallying cry and recruiting theme that has brought demonstrable results for the group, not only in recruiting foreign fighters but with locals that have witnessed these atrocities. Certainly, the lack of government accountability over military commanders – many of whom are complicit in the killings – reflects the very short term thinking that dominates the campaign to liberate Mosul and other areas from IS rule. The long term consequences of this behaviour will be a lasting bitterness that will make future reconciliation efforts much like planting flowers in the desert.

R&R Prisons – Rest, Recruitment and Return

Ideally, security forces would deliver suspected IS members into detention facilities with evidence for processing and holding until some kind of legal proceeding could determine innocence or guilt. This process is undoubtedly difficult during combat operations, and high standards of evidentiary procedures are probably hard to achieve by non-police and untrained militia members. Nonetheless, it would be prudent to make this a careful and deliberate process in order to deny IS the opportunity for yet another rebirth. Instead, many reports suggest that the current detention programme for IS members is precariously overwhelmed. While this would seem to be a relatively good problem to have, there is a serious downside to mass incarceration.

First, there is a significant amount of evidence that the key to the resurgence of the group after its defeat by other Sunni armed groups and tribes in 2008 was its manipulation of the government detention system. Islamic State operatives used the prison to network, recruit, train, organise, and consolidate; methods included bribing corrupt prison officials, executing jailbreaks, and quietly accepting poorly thought out pardons, amnesties, and parole before returning to the IS fold. Camp Bucca alumni include ‘caliph’ Abu Bakr (released in 2004), spokesman Abu Mohammand al-Adnani (2009), religious leader Abu Ali al-Anbari (2012), and hundreds more. This demonstrates that our collective ability to distinguish the wheat from the chaff is severely limited, and there is no guarantee that intelligence cooperation between local and foreign partners is currently sufficient enough to prevent what happened in the past from repeating itself, with the same tragic consequences.

A related problem follows: the low ranking IS members and innocent Sunni males incarcerated with hard core members – who are invariably adept and schooled in the ideology – will become the next generation of IS. Since they are considered of little significance to the government, they will eventually be released, allowing them to propagate and recruit – this time with added street credibility because of their prison time. This should be a familiar problem to western correctional officials, and yet, there has been little consideration given to this problem, as if it were Iraq’s problem alone. The external operations wing of IS should have disabused us of this notion, and yet I believe that no western government wants to go anywhere near this odious prison problem, for fear of being contaminated by the human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings described above.

Conclusion

Building on Kyle Orton’s article, my intention was to present concerns about some of the counterinsurgency tactics being used that could impact the future return of another IS organisation. The purpose was not to demonise Iraqis that are fighting the Islamic State, or criticise western governments supporting this effort. I am sympathetic to the front line soldiers and policemen presented with very real dilemmas of rooting out IS sleeper cells and weeding out fighters from refugees pouring out of Mosul. These security officials know that the people they detain quite often get released or bribe their way out, and a lack of faith in their government’s detention programme might cause soldiers and policemen, Sunni and Shia alike, to take matters of justice into their own hands. Many of these people have been fighting IS for over a decade, and have watched their society be ripped apart by IS tactics – which have killed both Sunni and Shia in large numbers. These abuses are not necessarily motivated by sectarian tensions, but rather a genuine motive to establish a lasting peace and security for the people of Iraq.

Unfortunately, illegal killings, mass incarceration, and other violations of the rule of law will generate their own second order consequences, and frustrate the goal of achieving peace. The phrases ‘political solutions’ and ‘societal reconciliation’ are used often when discussing a future ‘post-ISIS’ era, and they are uttered shortly after admitting that there is ‘no military solution’ to this problem. What is overlooked is that the military actions are influencing political and societal pressures, often in a negative fashion. The need to permanently defeat IS grows more critical every day. Policy makers and military officials need to be aware that how it is done is much more important than who does it or when it happens.

Comments are closed.