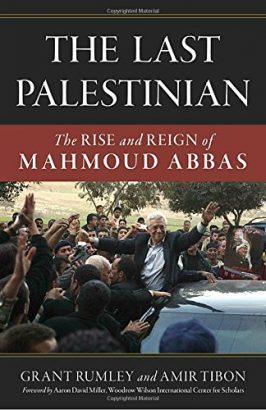

Fathom Assistant Editor Samuel Nurding sat down with Grant Rumley and Amir Tibon to discuss their new book The Last Palestinian: The Rise and Reign of Mahmoud Abbas (Prometheus Books, 2017). Rumley is a research fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and Tibon is the Washington D.C. correspondent for Haaretz. They discuss their motivations in writing the book, critically review the events that have shaped Abbas’s political thinking, and assess the legacy Abbas is likely to leave behind for the Palestinian people.

Introduction

Samuel Nurding: Why did you decide to write a study of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas?

Grant Rumley: We decided to write the book after the 2014 peace talks, driven by the US Secretary of State John Kerry, fell apart. It was clear that the White House was not going to reengage at the level they had in 2013-4, so there was a window for some deeper analysis. Amir and I were struck by the fact that there were no biographies of Abbas, who is as big a part of the equation as anyone, and we both believe that not enough attention is paid to Palestinian politics. We hope the book sheds new light and will improve the discourse about the peace process.

Amir Tibon: After the 2013-4 peace talks fell apart we both doubted that we’d see that level of seriousness again. Hopefully we will be proved wrong. Our thinking was that it was a good time to put out a definitive story about a person who has been so central to the peace process for the last several decades.

The Trump administration has been making some noises and sending some dignitaries. It doesn’t look serious to me, at the moment, but if it becomes serious then the book becomes very relevant to all the players. If the Trump administration wants to make progress on the Israeli-Palestinian issue, it needs to become more knowledgeable about Abbas.

Abbas and the early years

SN: Let’s start with Abbas’s early life. His family left Safed due to the 1948 war when he was 13. He was old enough to understand that event and to store memories of it. How important was 1948 for Abbas’s political thinking?

GR: It’s impossible to overstate the impact of the Nakba (The Arabic term for catastrophe, used by Palestinians to refer to the 1948 war) for the Palestinians. It’s a foundational moment of the modern Palestinian national narrative. After the Nakba Abbas becomes more involved with his father’s business, helping to raise his siblings and contributing to the family. He adopts a working class mentality to the consequences of the Nakba, moving first to Jordan and then to Syria, where he works in the day and finishes his education at night. Abbas has a very serious work ethic. His commitment to his family shines through his life, it’s really the highest priority for him.

In this period he realised that he was not suitable to be a soldier and that he needed to look at other ways to contribute to the Palestinian cause. He tried to join the Syrian military camp but was flushed out after two months when the military told him: ‘You’re not really cut out for this.’ So he decides to move to Doha, where he had connections, and he becomes a teacher. He then starts writing pamphlets and develops an interest in politics.

AT: Abbas’s political legitimacy is based on his early experience. He is not only the leader today, not only a founding member of the Palestinian national movement, but a man who can represent the whole Palestinian narrative and population in a way that future Palestinian leaders will not be able to do. This is something Israelis are not always very appreciative of. In Israel we like to talk reverentially about our founding fathers, the generation of David Ben-Gurion, and how we had leaders and people totally committed to the national project. This is the standing that the founding generation of Fatah, and especially Abbas, has on the Palestinian side. A large percentage of people involved or interested in the conflict are not fully aware or appreciative of this fact when they talk about Abbas.

SN: There are two moments in the 1980s that impacted Abbas greatly: the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the 1988 Arab League Summit. Can you explain how these two events helped to steer Abbas’s thinking?

GR: During the Israeli siege of southern Lebanon in 1982 Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) members started suggesting openly that the PLO might accept some type of two-state solution, as a way of breaking the siege. They saw the dire situation that they were faced with and became more receptive to the ideas that Abbas had been quietly putting forward about engagement and negotiations. It was a perilous time for Abbas to be advocating this. By the time the PLO arrived in Tunis, the PLO realised that Abbas’s school of thought was on the rise, and Palestinians had realised that they were no longer going to ‘liberate all of Palestine’.

The 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence and the renunciation of terrorism by Yasser Arafat was a vindication of Abbas. The years 1982-88 and then 1988-94 represent the arch of Abbas’s rise. There’s also a turnover within the PLO after Arafat’s two deputies, Khalil al-Wazir and Salah Khalaf, are assassinated. Abbas, who at the time was advocating back-channel negotiations with the Israelis, moves up from the middle of the pecking order in the founding generation to a position closer to Arafat. It’s Abbas’s programme that slowly becomes the modus operandi of the PLO.

AT: These events put the Israeli-Palestinian conflict into the framework it has been stuck in since that time. The war in Lebanon signalled to the Palestinians that their attempts to build military bases in Jordan, then Syria and finally in Lebanon to put pressure on Israel with terror or military attacks would not work, and that realisation shifted the whole PLO towards Abbas’s ideas. The [Palestinian] Declaration of Independence, coupled with Jordan’s end of claims to the West Bank, put Israel in a tough position because it realised it was stuck with the PLO and no longer had a Jordanian fall-back option.

SN: Abbas opposed Arafat’s armed resistance throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s and ‘risked his life’ in opposing the second intifada according to one senior Israeli official in the book. How difficult was it for Abbas to take a line against the use of violence, as he has done for decades?

GR: Abbas was well aware of the risks of advocating for the two-state solution at the time. Members of the PLO who were meeting with Israeli leftists in the 1970s and 1980s were being assassinated by rival Palestinian factions. There are two competing views of why Abbas has pursued peace negotiations for so long. One opinion thinks Abbas at times saw tactical merit to violence but never bought into it as a strategy and therefore thought negotiations were the best way forward. The more cynical view claims that Abbas believes that long drawn out conflicts end in negotiations and that if he could make himself the chief negotiator and expert on Israeli politics, then at a certain point in time he would ultimately be in charge.

Both of those strategies run a significant risk of blowback from his peers – a famous example is Issam Sartawi, who was assassinated by rival PLO groups for advocating recognition of Israel. It wasn’t until the Oslo Process in 1993 and the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) that Abbas had the political cover to advocate for negotiations and non-violence, because that’s the spirit of Oslo.

AT: The second intifada was a low point for Abbas’s relationship with Arafat. As we describe in the book, Abbas faced pressure from ‘the street’ to join the intifada but instead emerged as the most outspoken critic of that policy. Early on, Abbas warned Arafat about the dangers of his policy and how destructive it would be for the Palestinians. He was consistent with this position throughout the intifada, both in the opposition (although he was part of the establishment, he also became the de-facto leader of the opposition) and then when he became Prime Minister in 2003. Abbas’s opposition made Arafat very angry. At the 2003 Aqaba Summit, Abbas gave a speech in which he not only spoke against violence but didn’t even mention Arafat, something that pleased the Israelis and Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. This was the lowest point of the relationship. For Arafat, Abbas was a rising figure and a growing challenge to his power, as well as a man with international legitimacy. But perhaps more importantly for Arafat, Abbas represented an ideological break. All the discussions and disagreements in the 1970s and 1980s about the use of violence were less threatening to Arafat’s grasp on power than Abbas’s push for negotiations with Israelis. If you ask me, this was one of Abbas’s finest hours. But from there on the story changes.

Abbas the negotiator

SN: Let’s focus on Abbas’s role in negotiations in the 1990s. He was involved in two very important sets of peace talks, and in very different ways. The first was the Oslo Accords [and the secret Beilin-Abu Mazen agreement] and the other was the 2000 Camp David talks. In the book you show how instrumental Abbas was in concluding the Oslo Accords, yet you write of the Camp David Summit that the one consensus which emerged was that Abbas’s conduct had been unhelpful. How did Abbas change from the champion of the peace process in 1993 to the ‘least flexible negotiator’ at Camp David?

GR: In the years between Oslo and Camp David, the peace process becomes a contact sport for Abbas. Everything prior was something of an academic exercise for him – doing his research, writing his books and his controversial PhD thesis – where he was able to advocate a certain position and no one had to seriously debate it. When his strategy became the primary objective of the PLO, other actors become involved and Arafat was unprepared for this. As regards the secretly-agreed Beilin-Abu Mazen agreement, it’s the leak, the subsequent blowback from the Palestinian street and Arafat’s disavowing of what Abbas had compromised on, that killed the agreement. I regard this event as one of the seminal moments in his life. The negotiations and the positions in that agreement were consistent with what he had advocated and communicated in the past. The retaliation and blowback is completely new, and it shocked him and showed him how unequipped he was to combat criticisms of his policy.

You can see the roots of his behaviour in Camp David in the Beilin-Abu Mazen experience, not to mention that in the run up to the Summit, Arafat, typically, was playing his deputies off against one another. For example, he empowered Ahmed Qurei [Abu Ala] with a Swedish back-channel in the months before and Abbas was extremely upset when he found out. So Abbas entered Camp David paranoid, risk-adverse and unwilling to put his neck out because he had been burnt many times before.

AT: Abbas’s conduct at Camp David was a real surprise to a lot of Israelis who respected and appreciated him, as well as to the American team. The Palestinians were less surprised by his behaviour because – unlike the Americans and Israelis – they didn’t see the peace process as independent to Palestinian politics. The fact that he had been the earliest supporter of a two-state solution as well as the most consistent leader for negotiations and non-violence didn’t mean that Abbas was free from his own domestic political considerations too. Camp David was the moment this was exposed.

On the way to Camp David the Americans and the Israelis also made decisions that pushed Abbas into an uncomfortable position. For example the Americans gave Mohammad Dahlan a very large welcome and lots of invitations to talks and dinners, which unsettled Abbas. The Israelis contributed to his isolation and irrelevancy in the talks by including no one in their negotiation team who had prior history of dealing with Abbas (either before or after Oslo). We include one interesting story in the book concerning a senior Israeli official in [then Prime Minister] Ehud Barak’s office who said, ‘Why don’t we bring Yossi Beilin to Camp David because of his negotiating experience and his connection to Abbas?’ As we know, Barak was not convinced. We can ask a million ‘what ifs’ regarding the Camp David summit, but I think this is one of the more interesting what ifs – might a different approach by the US and the Israelis have produced a more effective Abbas?

GR: Amir brings up a really important point about Dahlan and the dynamic in the Palestinian negotiating team at Camp David. Abbas wasn’t prepared for the turf battles he had to fight once the PA was created and his mantra of peace negotiations became the driving force. When the PLO were in their camps in Lebanon, Abbas was in Syria or Tunis, always maintaining some distance, never considered to be one of the revolutionaries. But when Camp David came around, there were all these upstarts, whether it be Mohammad Rashid who was close to Arafat, or Dahlan, the kid from Gaza who grew up with the Fatah youth and the security services. So Abbas not only had to fend off people who were critical of his compromises in negotiations but he also had to fight Palestinian politics. Nothing in his career had prepared him for that, and the result was frankly disastrous for him.

Abbas the President

SN: Following the intifada and Arafat’s death, Abbas quickly rose to stardom as the next leader of the PLO and the President. Was he ready?

GR: In one sense, Abbas was ready to be president. He had the bureaucratic qualifications and closeness with Arafat and he was a driving factor in creating the PA. In another sense, he was ill-equipped. The consensus at the time of Arafat’s death was that the Palestinians would benefit from a leader who would a) reorient the Palestinians away from the intifada, and b) be able to speak to the Israelis and the Americans and be acceptable for the international community. This was Abbas. Abbas had shown he was a man of principle when he tried to take control of security in the West Bank and Gaza during his brief time as Prime Minister. What he lacked, however, was the ability to play the retail politics that Arafat had been the master of.

After his Presidential election victory, Abbas began a bureaucratic overhaul, trying to rehabilitate the PA after the intifada. But he didn’t have a sense of what was coming, and he didn’t have the skillset to maintain discipline or keep people like Dahlan and Marwan Barghouti from fracturing his Fatah party. Whilst he is an incredibly capable bureaucrat, he’s neither charismatic nor a great party leader. And that really decided his fate in 2006 when Hamas won the parliamentary elections.

AT: Abbas was qualified from the moment he took power – as Grant said, this was the time when the Palestinians needed someone to repair the damage from the second intifada and rebuild trust with Israelis and the Americans. But he was not ready. And readiness you can’t really know in advance, for any leader. You can ask the same question of Olmert, who won an election shortly after Abbas won his presidential election, and he was considered qualified and able to continue in Sharon’s path. It turned out that both Abbas and Olmert were unprepared for the events of 2006 – for Abbas the Hamas victory in the parliamentary elections and for Olmert the Gilad Shalit kidnapping and the war in Lebanon. That year deflated all the hope people had when both of these leaders won their respective elections, and it meant that what began under Abbas-Sharon, which was far from perfect but still preferable to stalemate, would continue.

SN: 2006 was a watershed year. In what ways did losing the parliamentary election and the subsequent civil war in Gaza set the terms for Abbas, his presidency and his political thinking towards the peace process?

GR: The years 2006 and 2007 are at the heart of understanding Abbas. In 2005 he had the popular mandate, the electoral victory, the support of the White House and tacit support from Israel. Yet that’s the last time he can legitimately speak for all Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. There are moments between the January 2006 election loss and the June 2007 civil war between Hamas and the PA in Gaza when some attempts at co-existence occurred. For example, Abbas tried to piece together a unity government, but it ultimately failed because Fatah and Hamas have ideologically different views of what a Palestinian society should encompass. Abbas didn’t have the ability to stave off the electoral defeat and challenge Hamas in any other way after that.

The year 2007 is sort of inevitable in this sense, and once the split happened, everything else from then on for Abbas is viewed through the primary prism of survival and consolidation of power. It’s a very simple choice for him: there was an assassination attempt on his life (which we talk about in the book) before the civil war in 2007, and I see this moment as being as significant for Abbas as the Beilin-Abu Mazen fallout was. It was the moment when Abbas realised that political disagreements with Hamas turned into assassination attempts – it became an issue of life and death. For a guy not accustomed to turf wars, who hadn’t come from the militant revolutionary background, and who was already paranoid and risk adverse, the assassination attempt became a bridge too far. He then concentrated all his political power on making sure that what might have happened to him in Gaza cannot happen to him in the West Bank. And it’s a large factor in his future peace negotiation stance.

AT: I agree with Grant; the election and war with Hamas is the moment where everything begins to slide away from Abbas. If this book were ever to be turned into a movie (not that I think there is even a one per cent change that will happen!) this is the point where the story line changes. Until that moment Abbas is the leader who, more than anyone else, is committed to peace and negotiations. And he had successes, not least the way that the realisation of the necessity of negotiations evolved in both the Palestinian national movement and in Israel, from total rejection of a Palestinian state to Ariel Sharon saying we need an end to the occupation. From 2007 onwards Abbas lost control over his ability to promote the agenda with which he had become identified. In the book we argue that the political divide within the Palestinian movement – the fact he didn’t control half of the population, and that Hamas was challenging the legitimacy of his government – are the key reasons for this loss of control.

At the end of the day, Abbas’s story is a tragedy. Maybe there will be a happy ending under the Trump administration, but right now it is a tragic story about the leader who wanted to do the right thing but could not deliver when it mattered most.

‘Palestine 194’

SN: In 2011, with the absence of a political process that he had championed and his legitimacy undermined by the absence of elections, Abbas adopted what has been termed as the internationalisation strategy. Was this the right strategy for Abbas to pursue at the time? And has the strategy paid dividends for Abbas?

GR: I’ve covered ‘Palestine 194’, as the strategy is dubbed, a lot since I lived out there and interviewed people who formulated the policy right up to Abbas’s UN General Assembly speech in 2011. From a negotiating standpoint I see why it came about. In its initial stages Abbas and his key advisors saw merit to widening the scope of negotiations to include international actors, and even in recent weeks one of Abbas’s advisors publicly stated that if negotiations under the Trump administration do not work out then they will turn to Angela Merkel. There has definitely been a growing sense in the PA in recent years that more international actors involved in the peace process will mean more international allies for Palestinians, while the UN is home court for the Palestinians.

‘Palestine 194’ made sense early on for Palestinians when they threatened to join international bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC), but then the PA rushed things. In 2015 it joined 15 UN bodies and there was a kind of ‘emperor has no clothes’ moment. Israel realised that these moves were nuisances but not game changers. Even ICC investigations are bogged down in international law purgatory. The internationalisation strategy always worked much better as a threat to get back to negotiations or, from the Palestinian perspective, as a way to strengthen their hand in negotiations. Since joining these bodies, how many more arrows do the Palestinians have in their quiver? There is talk about joining Interpol but the threat has stalled and even possibly backfired.

On the other hand, the strategy has led to noticeable accomplishments: the upgraded status of Palestine to non-member observer status at the UN in 2012 and UN Security Council Resolution 2234 are big wins for the Palestinians. You can still see pictures in the West Bank of Abbas delivering his speech at the UN. But at the end of the day they don’t really change the reality on the ground, and they don’t advance the peace process. Instead, the internationalisation strategy reinforces the notion that a solution to the conflict comes down to the two parties in bilateral negotiations.

AT: The internationalisation strategy hasn’t promoted Palestinian statehood but it could have had a greater impact if Abbas had made different calculations during the last round of peace talks in 2014. It is not 100 per cent clear who should take the blame for the fall of those talks. Netanyahu made some compromises during the talks despite recently denying them. But the fact that Abbas did not give a clear answer to Obama’s peace framework hurt his own internationalisation strategy. After all, what is this strategy supposed to be built on? On the notion that the Palestinians want peace and Israel objects. I personally think Netanyahu has done very little to help the two-state solution become a reality, and if Abbas had said yes to Obama’s framework it would have put Netanyahu in a very difficult position. Abbas would then have been strengthened on the international stage. In 2014 momentum was building for the Palestinians; many parliaments voted to recognise Palestine, and if Abbas had excepted the US offer – and Netanyahu hypothetically refused it – Abbas could have said, ‘What are we supposed to do now?’ But he wasn’t able to do that, and that really hurt his own international campaign.

SN: What about the recent Palestinian push to get FIFA to ban the Israeli football governing body? Unlike other UN bodies, FIFA has the potential to get more people talking about the conflict perhaps in ways not beneficial for the peace process. Do you think the FIFA push will have any significance?

GR: It could change some realities for soccer federations on both sides, but the road to statehood doesn’t run through FIFA, like it doesn’t run through the UN Convention for Biodiversity, which the PA joined in 2014. Ultimately it’s theatrics to me; no longer a strategy, only a way to attack and counter-attack in the international community.

Lord of the Palestinian court

SN: Amir, you mentioned the 2014 peace talks, when Abbas didn’t give President Obama an answer to his peace framework proposal. You write in the book that ‘Abbas’s reaction [to Obama] was one of the most telling moments of his presidency’. What do you mean by this?

AT: In our opinion it was a crucial moment in Abbas’s presidency. There are people who say that Abbas’s lack of response to Obama in 2014, as with Olmert in 2008 and Arafat’s silence to US President Clinton in 2000, represents a pattern. Our analysis suggests there is also an argument to make that these events represent three very different circumstances. There are questions over how serious Olmert’s offer was to Abbas, given his domestic political weakness at the time. And 2014 was a different situation for Abbas than Arafat in 2000. The offer in 2014 came from a sitting US president with more than two years in office (Clinton in 2000 was about to depart), who had convincingly won re-election and had a majority in the US Senate, and it was an offer that he could have used to put more pressure on the Israelis. Yet, there were complicated domestic Palestinian issues: the competition with Hamas; internal strife within Fatah and the PLO; and the risks of upsetting and losing public support. Ultimately those factors outweighed the goal of putting pressure on Netanyahu.

Obama told Abbas that there would not be another sitting US administration as committed to this issue as his administration. I will be very surprised if the Palestinians get the same kind of proposal from Trump who – all the signs so far suggest – will be a different kind of negotiator.

SN: What in your mind is Abbas’s greatest achievement to date, his greatest mistake to date and the legacy he will leave behind for Palestinians?

GR: His greatest achievement is the Oslo Process and bringing and solidifying the two-state solution into the Palestinian political discourse. For me the culmination of that process was this year’s Fatah Congress. I sat through his three hour speech to members of his own party, where he defended his decisions to go to Oslo and talk with Israelis and gave a hearty defence of the two-state solution and the non-violence approach. I look back at the conflict and these were the things we begged Arafat to do – he was famous for saying one thing in Arabic for his own audience and another thing in English to the international community. Yet this is what Abbas is willing to stake his legacy on. He brought the notion of peace into the accepted Palestinian framework for statehood and, if nothing else, that is his greatest achievement.

That does not mean his legacy hasn’t been diminished because, like Amir said, his greatest mistake was not accepting the Obama proposal. You can’t really ask for a better situation, from a Palestinian standpoint, than having your leader sitting in the White House with a US president, two years left on his term, willing to go to bat for you vis-à-vis the Israelis. And I think his legacy will be that of missed opportunity. Shimon Peres called him the greatest partner for peace because of his role in Oslo, but ultimately his deficiencies outweighed his strengths and he will likely leave a quagmire.

AT: I want to offer one defence of Abbas. When we talk about a missed opportunity it works both ways because Abbas is also a missed opportunity for Israel – especially when you look at the entire gallery of Palestinian and Arab leaders. There have been Arab leaders much more powerful than Abbas, and better able to withstand greater public pressures or attempts to question their legitimacy, who have shown much less courage than President Abbas when it comes to peace talks, normalisation with Israel and even open discussions with Israeli leaders. There is a tendency now to say that Israelis, the Americans and the international community don’t need Abbas, and can work with other Arab leaders for a regional peace. They are wrong. There are very powerful Arab leaders in the region who have secret relations with Israel but do not dare to do anything in the open. But there is still Abbas, much weaker, with internal constraints and who isn’t perfect, but has taken real risks for peace. The fact he will soon to leave the stage with his life project incomplete is a big loss for all sides.

SN: What message are you conveying with the title of your book, The Last Palestinian?

There are several layers to The Last Palestinian. First, Abbas is very likely the last leader who can personify the arc of the modern Palestinian national narrative. He is one of the last Palestinians, and likely the last President, to be able to say, ‘I was a refugee; I experienced 1948; I was with the PLO abroad and came back to be one of the founding fathers of the Palestinian national movement’. After him there will be a push for a second generation of Palestinian leaders who came of age during the last two to three decades, but none with the experience and legitimacy that Abbas holds.

Second, Abbas is the last man standing. He began his presidency with control over the West Bank and Gaza but then lost Gaza. And then he started forcing out the technocrats, like Salam al-Fayyad, and independents like Yasser Abed Rabbo. Then his party fractured and he purged members of the Dahlanists. He’s basically kept together the same kitchen cabinet since he became president. It’s a shrinking crowd of people and he can therefore be the last man standing.

And thirdly, the title was originally written for Arafat in a famous eulogy by Hussein Agha, one of Abbas’s negotiating proxies in the last 20 years. Agha said that the days of Arafat’s retail politics were gone, and the days of bureaucracy and transparency and accountability were in. That judgement ultimately didn’t age too well because Abbas has arguably had more control over the PA than Arafat ever had.

AT: There is also the question of whether Abbas is the last Palestinian leader working to promote the two-state solution in the Palestinian space. If he is, the question is not only ‘what is next for the Palestinians?’, but also ‘what is next for Israel?’ After Abbas, are we on the road towards a one-state solution? These questions were another factor in choosing this particular title.

Comments are closed.