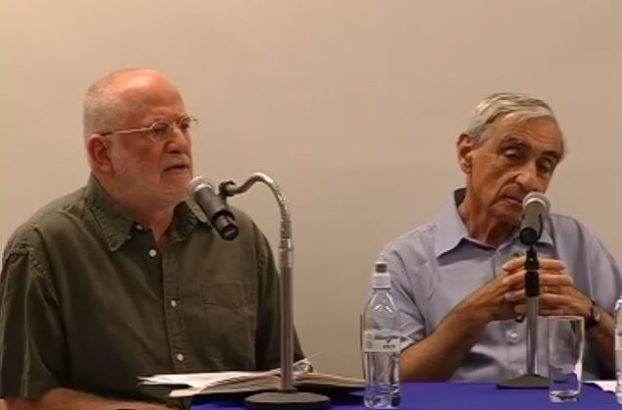

Writing in Fathom Michael Walzer responded to the discussion of diaspora Jews in Chaim Gans’s book A Political Theory for the Jewish People. Here Gans writes a rejoinder.

I’m very grateful to Professor Michael Walzer for honouring me with his response to my book A Political Theory for the Jewish People. He sympathises here with my account of Jewish existence outside Israel because the egalitarian interpretation of Zionism for which I argue, and on which my views on Jewish existence outside Israel are based, does not imply that all Jews should live in Israel. It only implies that not all Jews should live outside Israel. It therefore interprets Jewish life outside Israel as diasporic rather than exilic. This is in sharp contrast with the logic of the Zionism prevalent in Israel, which reflects the proprietary version of this Jewish ideology according to which all Jews should live in the Land of Israel.

Walzer is right in emphasising that, according to my egalitarian interpretation, the success of Zionism has led not only to the establishment of a Jewish political and cultural entity in the Land of Israel, but also to a radical change in the nature of Jewish existence outside this land: the change from exile to Diaspora. In this respect my interpretation follows the early visionaries of Zionism, Leo Pinsker and Theodor Herzl, who also hoped that Zionism would affect Judaism not by bringing all Jews to Palestine, but rather by changing the status of all Jews as a consequence of making many of them politically and culturally self-determining in Palestine.

However, Walzer criticises my view of Jewish Diaspora: he argues that, because it is based on the liberal value of personal autonomy and freedom, it does not accommodate the justifiable disapproval on the part of committed members of Diaspora communities towards members of their communities who walk away.

I don’t think my account precludes such disapproval; it merely prevents such disapproval from turning into oppressive demands, and it requires that critical attitudes, and especially the ways they are expressed, should be adapted to the particular circumstances in which they emerge. Nor is my account of Jewish diasporic existence outside Israel (as well as Jewish national existence inside Israel) based only on the liberal value of personal autonomy, since according to liberal thought personal autonomy cannot be the only substantive value people are allowed to hold. People must have other values to choose from in order to activate their personal autonomy and make up their life plans, and one such value is communal belonging, especially to historical communities. (Other possible values that serve this purpose include family belonging, friendship, and professional self-realisation.) It is on this value of communal belonging that my (autonomy-subordinated) egalitarian Zionism is based.

People who value belonging to an historical community do so because they were born or grew up inside these communities. They did not choose the particular communities into which they were born or within which they grew up. This is the sense in which Walzer’s autobiographical note ‘I don’t remember ever being asked, when I was twelve and studying my Torah portion, if I actually wanted to become a bar mitzvah’ rightly implies that, once he decided to attach great value to the political communities to which he belonged, he necessarily attached great value to Judaism. As far as I know, he did the same with regard to his Americanism. Serbism is not and was not an option for him.

This is different from the case of parental relationships. Here individuals are limited twice, not once: morally speaking, they cannot opt out of these relationships to their children, and they cannot choose children other than their own in order to realise the value of having parental relations. Peter Singer (like Walzer, a Jewish moral theorist at Princeton) once told me that as he approached the age of 13, his cousin started attending Sunday school to study for his bar mitzvah. Singer’s parents asked him whether he would also like to have a bar mitzvah. So, unlike Walzer, Singer was asked whether he would like to have a bar mitzvah. I think the difference can be explained by the different choices the parents made regarding the role of communal belonging to Judaism in their own lives.

Such choices may be open to moral criticism, but I believe that the strength of the criticism in any particular case depends on a great variety of factors, many of which potential critics are unfamiliar with. For this epistemic reason, we should usually refrain at least from voicing such criticisms. I say ‘usually’ and not ‘always’. This means that my position is not very different from Walzer’s. We both think that Jews should be allowed to walk away, and we both think that sometimes it is right to criticise them for doing so (and to voice this criticism). But whereas Walzer emphasises the possibility of criticism, I would emphasise the need to discipline ourselves when considering making it.

Walzer comes close to claiming that the possible moral criticism engaged Diaspora Jews might direct at less engaged Jews creates a kind of hierarchy between them. He believes I would object to such hierarchies, and associates my imagined objection to another objection he imagines I would make, namely, to the claim that in Israel ‘Jewish symbols, holidays, memories, and histories can be represented in public space, can shape the state calendar, and can determine (but not alone) the curriculum of state schools’. But I wouldn’t make any of these objections. As for the first: in the same way that some musicians, as musicians, are better than other musicians, so that there is a musical qualitative hierarchy among them, so some Jews are better as Jews than other Jews in a way that establishes a hierarchy among them qua Jews.

As for the second objection, I would surely not make it. I argue against such an objection in all my writings on nationalism and Zionism. I argue instead for the collective rights of ethno-cultural nations such as the Jews to have in their home countries their ‘symbols, holidays, memories, and histories [that] can be represented in public space, […] shape the state calendar, and […] determine (but not alone) the curriculum of state schools.’ This creates a hierarchy between homeland nations and immigrant groups in different counties: immigrant groups do not have such collective rights whereas homeland nations do have them. Since the Jews are not the only homeland group in Israel – the Palestinians there also constitute such a group – I think there should be no hierarchy between the Jews and the Palestinians in Israel in respect of their collective national rights (unless there are special reasons to give them lesser rights – e.g., because there is a separate Palestinian state, which also makes their numbers under Israel’s control much smaller, and this in itself establishes an equality-based reason to grant them lesser rights in terms of their territorial extension in the country). I took this view to justify calling the Zionism I’m arguing for ‘egalitarian,’ as opposed to Walzer’s hierarchical view, which justifies a hierarchy in Israel not only between Jews and groups such as Philippines who immigrated to Israel, but also between Jews and Palestinians.

Comments are closed.