Daniel Monterescu is the author of Jaffa Shared and Shattered: Contrived Coexistence in Israel / Palestine.[1] An anthropologist and a Jaffa-born expert on mixed cities, his other books include A Town at Sundown: Aging Nationalism in Jaffa (with Haim Hazan) and Mixed Towns, Trapped Communities: Historical Narratives, Spatial Dynamics, Gender Relations and Cultural Encounters in Palestinian-Israeli Towns (editor with Dan Rabinowitz). An associate professor of urban anthropology at the department of sociology and social anthropology at the Central European University in Budapest, Monterescu is now Lady Davis Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, the Technion in Haifa. Alan Johnson is the editor of Fathom. They spoke about a ‘political and social laboratory where the traumas of dispossession and the hopes for a better future play out in everyday life’ in December 2016.

Part 1: Personal and Intellectual Influences

Alan Johnson: Can you say something about your family background and the major influences on your intellectual development, and how these have helped to form the characteristic concerns of your work?

Daniel Monterescu: The story of my family is deeply intertwined with the history of the city. My father immigrated in 1951 as a boy from Romania and after a transition period in a Ma’abara settled in Jaffa. The neighbourhood of Manshiyya, which was historically a working-class Palestinian district bordering on Tel-Aviv, was completely demolished in the 1960s as part of a ‘slum clearing’ operation, but in the 1950s it was still a bustling migrant town, full of Jewish newcomers from Central Europe, the Balkans and the Middle East. The Palestinians in that context were of course present in their absence, as they were largely confined to the ‘Ajami ghetto’. After marrying my mother, herself a war refugee born in France to German and Swiss Orthodox parents, my parents moved to Jaffa D., a neighbourhood on the Southern edge of the city, which also had a significant Arab population living in orange orchards (biyarat). My experience growing up among such ethnic diversity and political controversy nurtured me as an apprentice ‘stranger’– a fundamental sensibility which I turned into a profession as an anthropologist.

It is however my studies at the catholic Collège des Frères, where I learned Arabic and French, and where I was often the only Jew in class, that enabled me to develop my observation skills and multifocal approach to the city. This school, founded in 1882 as part of the French ‘mission civilisatrice,’ catered to both the Jewish and Palestinian elites prior to 1948 and counted among its students members of the Chelouche family but also Palestinian personalities such as writer Ghassan Kanafani. After 1948 it continued to serve the Arab community and a handful of Jews and diplomats whilst retaining a cosmopolitan environment that allowed me to look at both the Arab-Palestinian and Jewish-Israeli life-worlds from critical intimate distance.

Part 2: Mixed Cities

AJ: Let’s talk about ethnically-mixed towns in general, before we talk about Jaffa specifically. Jaffa, Ramle, Lydda, Haifa, Acre are exceptional places, you note, as ‘more than 90 per cent of the Palestinian citizens live in Arab towns and villages and an overwhelming majority of the Jewish citizens reside in towns with no Arab population to speak of.’ What are the most important characteristics of these mixed spaces, and what they might tell us about Israel’s future?

DM: Ethnically mixed towns are the only urban spaces in Israel that defy the ruling principle of ethnic separation. This however was not a planned strategy but rather the unintended consequence of a long history of displacements, immigration and more recently gentrification. In a sense these cities are the exception that confirms the rule, but precisely this exception sheds lights on the tribulations of what I like to call the violence of coexistence. This is why, despite their modest population size, mixed towns occupy a disproportionately important place in Israeli and Palestinian public discourse and national imagination.

The definition of a (Jewish-Arab) ‘mixed town’ which I propose in the book is two-pronged. One element of it is a straightforward sociodemographic reality: a certain ethnic mix in housing zones, ongoing neighbourly relations, socioeconomic proximity, and various modes of joint sociality. The second element is discursive, namely, a consciousness-based proximity whereby individuals and groups on both sides share elements of identity, symbolic traits, and cultural markers, which signify the mixed town as a shared yet contested locus of memory, affiliation, and self-identification.

Jewish attempts to (re)claim the mixed city. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2007.

Jewish attempts to (re)claim the mixed city. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2007.

The term ‘mixed towns’ itself (‘arim me‘oravot in Hebrew, mudun mukhtalata in Arabic) is highly politicised and has had a checkered history in Palestine/Israel. It was and still is used by Israelis and Palestinians in diverse historical and political contexts, serving a number of discursive goals and altering definitions of the urban situation. From its first mention in the report of the Peel Commission (1937), formed after the outbreak of the ‘Arab Revolt’ (1936–1939), to this day it is used to denote both coexistence and enmity depending on the speaker. To the best of my knowledge, mixed towns in Israel are the only group of cities in the world that are identified as such in public discourse. While many cities worldwide exhibit different degrees of ethnic mix, only in Israel do they make up a marked category. My goal was to position this concept and the realities it describes in a more historical and ethnographic context, in everyday life.

AJ: You cite this view: ‘Mixed towns are a metaphor for the entire Israel-Palestinian conflict.’ Do you agree with that and what does it mean to you? You also make the case that, ‘embodying both the impasse and the hope of minority-majority relations in Israel, mixed towns are likely to remain pivotal for the region’s future’. What is the impasse and what is the hope?

DM: I cited this statement made by two Israeli journalists who documented the events in mixed towns in the aftermath of the October events in 2000 to point to the prevalence of the discourse in public debates. Cities like Jaffa and Acre were projected with the anxieties and fantasies of many Israelis. But inasmuch as sites of Jewish-Arab interaction are a barometer to the vicissitudes of Palestinian-Israeli conflict I agree with the statement. The argument is that if real coexistence can be achieved in these cities it can be achieved elsewhere. In that respect mixed towns are a political and social laboratory where the traumas of dispossession and the hopes for a better future play out in everyday life. It is also why I see in these cities more than the sum of their parts. While at present they exhibit mainly the darker side of majority-minority relations in Israel, they could in the future serve as the starting point of reconciliation and recognition.

AJ: Mixing happens in different ways, of course. You have pointed out that ‘it is the newly mixed towns — originally planned as Jewish enclaves and recently reconfigured due to the migration of middle class Arabs to Jewish cities such as Nazareth Ilit and Carmiel — that might herald the collapse of the exclusionary ethnic segregation policy’. I was struck by this potential when I was in Nazareth. Also by how much of a battle some people are putting up to stop it.

DM: Nazareth Illit is an excellent example of how the forces of real estate and urban capitalism run counter to the segregative forces of ethno-nationalism. Due to urban asphyxiation plans which did not allow Arab Nazareth to expand, Palestinian gentrifiers, namely upwards mobile professionals with sufficient resources, have been settling in Nazareth Ilit for almost three decades now. It is currently estimated that Arabs (mostly Christians) number about 20 per cent of the total population despite tremendous efforts made by a series of anti-Arab mayors. Similar scenarios can be observed in other town like Carmiel. It is a lesson for planners and politicians that unintended consequences are often more likely to occur than Judaising policies. The future of this country cannot but be mixed if we are to respect basic human rights such as equality under the law and freedom of movement.

AJ: You hint that mixed cities suggest an imaginary of a solution to the tragedy, ‘enabling historical reconciliation’ not least because of ‘the pragmatic necessities of communal survival, social exchange and spatial cohabitation’. Can you expand on that intuition?

DM: As an ethnographer and historical anthropologist my vantage point is a bottom-up approach to social relations and ethnic politics. Following the history of social movements and collective mobilisation, such as the 2011 Social Justice Protest, which led to an unprecedented coalition between the Jaffa Palestinians and Jewish Mizrahim in Schunat Ha-Tikva, I witnessed how the yearning to normalcy and dignity facilitate cooperation. Thus mundane struggles for affordable housing, better schools and the safety of women against gender violence become a leverage for civic action that can yield political solidarity. The recent mobilisation of feminist activist against ‘honour killing’ in the wake of the murder of two Arab women in Jaffa was such an instance when Jewish and Palestinian publics came together to voice their protest.

Part 3: ‘Contrived Coexistence’ in Jaffa

AJ: Let’s turn to Jaffa. You tell us it is about the size of a neighbourhood in Chicago. There are lower-class Jews, gentrifiers and the Palestinian population, which is itself divided. In 2012, the Palestinian minority was about 30 per cent, or some 15,000 out of a population of 45,000. You take the reader through five distinct phases or ruptures of the city’s history. Since 1948 Jaffa has, you say ‘witnessed the rise and fall of different communal and state-initiated projects’. And you foreground, I think the ‘anxious representations’ have characterised the collective memory of the relationship between Jaffa and Tel Aviv. The key concept you use to grasp the sheer complexity of the ethnic relations, the urban regime, and the ‘contested nature of binational urbanism’ in Jaffa is ‘contrived coexistence’. Can you unpack the concept for us and say why it has explanatory power for you?

DM: When I studied at the University of Chicago I was always struck by how complex, enigmatic and multi-layered Jaffa is in comparison when it’s not much larger than Hyde Park. I was looking for words to describe this complexity that define the city. By ‘contrived coexistence’ I mean the combination of violence, constraint and choice that mark life in mixed cities – their appeal and notoriety. Some critics have rejected the very notion of mixed spaces as being both exceptional and involuntary, while others have overemphasised moments of cooperation. Against these debates, the concept seeks incorporate the involuntary nature of Jewish-Arab cohabitation with the creative agency and survival tactics of its residents. Going beyond simplistic urban dualities of black and white, I wanted to point to ongoing intertwined processes whereby Arab and Jewish spaces are constantly made and remade, shared and shattered. By virtue of a history of Jewish immigration, slum-clearing policies and gentrification what we see in Jaffa is not one ethnically homogenous urban space or two divided parts but living Jewish spaces within Arab spaces and Palestinian spaces within Israeli ones.

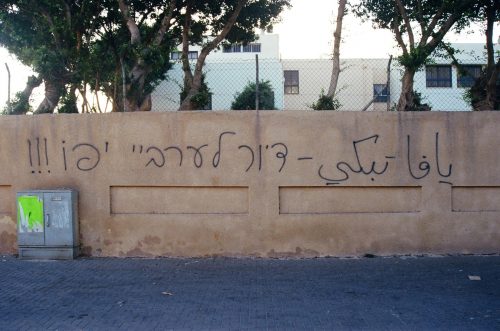

Graffiti in the gentrified ‘Ajami neighbourhood by the Popular Committee for Land and Housing Rights: ‘Jaffa Weeps [in Arabic] – Housing for the Jaffa Arabs!!! [in Hebrew]’. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2010.

Graffiti in the gentrified ‘Ajami neighbourhood by the Popular Committee for Land and Housing Rights: ‘Jaffa Weeps [in Arabic] – Housing for the Jaffa Arabs!!! [in Hebrew]’. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2010.

This material reality stands in sharp contrast to dualistic metaphors of East and West that we know from Jerusalem, or North and South as in Tel-Aviv. Put differently, the intersection of urban spaces corrupts the correspondence between spatial boundaries (that would delimit neighbourhoods) and social boundaries (of a certain class or ethnicity). In Jaffa as well as other mixed towns in Israel, the coupling between space and identity collapses.

AJ: You take a relational approach to Jewish and Arab communal histories, inviting the readers to see not two wholly separate, integral and autochthonous histories but rather something much more interesting beneath the official narratives: interaction, mutual constitution, even hybridity. Would it be fair to say that is the main theme of the book, this co-mingling of ‘cultural reciprocities and structural inequalities’?

DM: My own biography and intimate familiarity with the different webs of affiliation in Jaffa pressed me to write ‘a native’s book about his city,’ as Walter Benjamin once puts it. That is to address the story of the city itself as more than the sum of its separate communities (Palestinian Arabs, veteran Jews, Jewish gentrifiers and most recently settlers). To understand such complexity I sensed that we need an alternative approach to community studies, indeed a new conceptual language that doesn’t take for granted ethnic and national categories. The perspective of relationality allowed me to think of spaces of interaction and conflict dialectically. To render visible what is often silenced, such as collaboration between Jewish and Arabs crime networks and drug dealers, joint businesses and mixed marriages. Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish articulated beautifully this sociological paradox: ‘Me’ or ‘Him’. Thus begins the war. But it ends with an awkward encounter: ‘Me and him’.

AJ: In the 21st century, Tel Aviv has embraced Jaffa, introduced a policy of affirmative action and ‘removed the hyphen’. And yet – this is my reading – you do not credit this shift as being the progressive move that the architects and policy-makers present it as. Why? Is there really nothing progressive about this? Can’t even the slightly crass pursuit of ‘authenticity’ have a progressive underside of at least trying to know, to learn, to appreciate, to make contact?

DM: The history of Jaffa is inextricably linked to Tel-Aviv but it also reveals a troubling oedipal complex between these two rival cities. We should recall that Tel-Aviv started in 1909 as Jaffa’s modern Jewish suburb (ahuzat bayit) only to outpace its mother-city and eventually take it over during the 1948 War and officially annex it in 1950 baptising the new city as ‘Tel-Aviv-Jaffa’. Once the ‘Bride of Palestine’ and hence Tel-Aviv’s enemy, and then its disinvested ‘Arab backyard,’ Jaffa is now embraced by its ‘daughter-turned-rival’ global city. Heralding this rediscovery as a form of corrective historical justice, Tel-Aviv Municipality has recently launched a neoliberal planning policy of so-called affirmative action, but the result is mainly the depoliticisation of its creeping gentrification. While there are many good intentions involved, the main process you describe as ‘embrace’ is in the end of the day about real-estate takeover, profit and expansion. While some individual actors – planners and gentrifiers – are indeed progressive the ultimate systemic outcome is the commodification of space and the dispossession of the Palestinian underclass. We should also keep in mind the big picture – that since the beginning of the twentieth century to the present, the troubled relations between Jaffa and Tel-Aviv lays bare Zionism’s inability to come to terms with the unsettling presence of Jaffa’s Arabness.

Part 4: ‘Everyday binationality’

AJ: I was struck by an expression you used – ‘everyday binationality’ – and a claim you made: ‘Everyday binationality is far more ominous than any theoretical experiment or political musing might be’. What do you mean by ‘everyday binationality’? Ominous for whom?

DM: Since the establishment of the State, the spectre of binationality triggered anxieties and fears of Palestinisation among most Israelis. This is of course understandable, but these fears often turn violent. Most recently the arson attack on the bilingual school in Jerusalem and the public turmoil caused by LEHAVA militants around a case of mixed marriage in Jaffa prove beyond any doubt that the stakes are higher than mere theoretical musings. I think it’s high time to confront reality and recognise that in mixed towns binationality is a social fact. In my ethnography I tried to point to moments of everyday binationality that could lead not only to secession but also to unexpected coalitions, progressive social movements and radical cultural projects like Anna Loulou and the Yafa Cafe.

AJ: Some of the most powerful passages in the book, I thought, were those exploring the complexity, multi-layered and contradictory character of the relations between the peoples. You write: ‘These neighbours inhabit two incommensurable existential planes: while the Zionist national story unfolds from diaspora to immigration (Aliyah) and from Holocaust to national-building, the Palestinian collective narrative is one of traumatic passage from “the days of the Arabs” to the national defeat of the Nakba and its ensuing resistance (Muqawama) and steadfastness (Sumud)’. The life stories you discovered are about ‘a whole universe of contradictions and complexities’. How do people handle in practice the tension between incommensurability and the ‘creative agency of interpretive subjects’ and how did you capture that tension in theory?

DM: In the chapter ‘Escaping the Mythscape’ I draw on a separate collaborative research that came out as a book in Hebrew (with Professor Haim Hazan). I documented life stories of elderly Jews and Arabs, who, from their perspective of generational marginality, radically deconstruct notions of both Palestinian and Jewish nationalism. The biographical narratives of aged persons who are at liberty to criticise the violence of territorial nationalism, reveal a perspective that has often been silenced by both Israelis and Palestinians. The experiences of ordinary people on both sides of the fence are not only intertwined but are inherently mirror images of each other – though uneven and distorted, to be sure. These refracted images reflect comparable fears and longings for future coexistence and political recognition.

One such story took place during the 1967 War when a Jewish and an Arab family shared the same house (a common practice in the first decades in Jaffa) and anxiously listened to the reports from the battlefield together. When Israeli victory was announced the Arab father got up in anger and exclaimed: ‘OK. You won.’ But they continued to live and work together, sharing the kitchen and bathroom. One of the fascinating findings of the study is that in old age, the power of nationalism wanes rather than increases. Many of the interviewees engaged a deep sense of betrayal by the political leaders, the local community, the state and the grand narratives they represent.

Part 5: A New Discourse of Collective Rights

AJ: You discern a new discourse of collective rights among the Palestinian Arabs of Jaffa and the other ‘mixed cities’ in the 21st century. You quote a powerful statement by Buthayna Dabit, the head of the Shatil ‘Housing Forum’ as an example of this discourse. When did this discourse emerge, why, and what political and cultural forms is it taking?

DM: A new discourse of rights emerged with the disillusionment of Arab local politics from the bear hug of the Zionist parties such as Labor and even Meretz. Sociologically it can be traced back to the rise of what Dan Rabinowitz and Khawla Abu-Baker called the ‘stand-tall generation,’ which played a prominent role in the October 2000 events. Highly educated (in universities in Israel and abroad), ideologically motivated, and politically engaged, this generation no longer deems liberal ‘coexistence’ the magic cure to the Palestinian-Israeli predicament and calls for political recognition and cultural autonomy based on a national discourse of rights. Paradoxically, this generation exhibits high level of Palestinisation and Israelisation simultaneously – the more they make assertive claims in national terms as Palestinians, the more they integrate de facto in Israeli economy and civil society as citizens.

AJ: You believe that the demand that Jaffa’s Arabs, and Israeli Arabs in general, choose between their Israeli and Palestinian identities is ‘simplistic’ and ‘arrogant’. Is that arrogance on the rise or is it falling? How seriously does the Israeli left take the need to develop a politics of and for the Arabs?

DM: This arrogance, which would be deemed anti-Semitic if applied to Jews in the UK, is clearly on the rise as the political climate is turning right and downhill. Moreover, bystanders who remained silent when Arab critical voices were ostracised are now facing a similar fate. This is not anymore just the sectoral problem of the Palestinian citizens although they pay the highest price for the sea change. Any sign of dissent is now toned down if not silenced altogether. Breaking the Silence, which is made up of veteran soldiers and concerned citizens, is publicly blacklisted and even the Association for Civil Rights in Israel is under attack. In mixed cities Arabs feel this pressure every day and increasingly so as they lose their jobs and face police brutality. This leads to a withdrawal of the political that we know from authoritarian regimes.

The crisis of the Left is one of the tragedies of our time. The Israeli Left failed miserably in standing up and practicing what it preaches – the values of democracy, equality and freedom of expression. It should come therefore as no surprise that this ongoing spinelessness backfired and young Arab voters lost confidence in the Jewish-Israeli Left. Growing alienation could spiral out of control if the Left doesn’t sober up and formulae a truly progressive agenda, which might save it from itself and the suicidal path it has taken since 2000.

Part 6: Neoliberal Jaffa

AJ: You discuss the most recent transformations in Jaffa under the label ‘neoliberalism’. Before we explore the transformations it has wrought, can you give our readers a definition of ‘neoliberalism’?

DM: In a jungle of different theories of neoliberalism, the approach I find most useful singles out the hollowing out of the welfare state through the marketisation of society on the one hand, and the emergence of a new entrepreneurial subject on the other. In cities, this double process manifests itself through the arrival of gentrifiers and the emergence of gated communities.

AJ: Can you tell us about the significance of the Andromeda Hill project and the meaning of the attempt to ‘live authentic’?

DM: The marketing slogan of one gated community in Jaffa encapsulates this social logic. ‘To Buy or Not to Be’ thus becomes a civilising mission programmed to destroy the collective structures capable of resisting the precepts of the ‘pure market’. By dissolving the bonds of sociality and reciprocity and submitting them to the laws of the market, neoliberalism gives rise to an intense preoccupation with safety and security and to an obsession with their emotional corollaries – risk and fear. Paradoxically, urban risk society’s search for certainty perpetuates a self-defeating cycle, which reproduces the very alterity it seeks to eliminate.

Marketing the gated community: ‘To Buy or Not to Be’. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2005.

With its hollowing out of sociality, urban neoliberalism reduces lived space to a commodity to be consumed, and thus exposes place and property to theft, transgression, and pollution. In search of a secure form of social organisation – protected from the urban chaos lurking outside – gated communities arise as the spatial and cultural nexus for a new discourse of fear of violence and crime. While operating chiefly as a mechanism of depoliticisation, gated communities in Israel lead inevitably to the extreme ‘enclaving’ of social inequalities and hence to the politicised spatialisation of privileged ‘outsiders,’ thus in turn crystallising militant local discourses of rights around the politics of their ethnonational identity and class struggle.

Andromeda Hill’s monumental presence, bordering on older structures that were later demolished. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2003.

Andromeda Hill’s monumental presence, bordering on older structures that were later demolished. Photo by Daniel Monterescu, 2003.

The Andromeda Hill gated community is a case in point. Since the advent of gentrification in Jaffa in the 1990s it has been the flagship of the real-estatisation and commodification of space. What is unique here, however, is the romantic and neo-Orientalist coating of the project, which attempts to achieve the impossible task of positioning itself both within and outside local lived space and inhabited time. The trick of marketing high-end luxury apartments at the heart of a highly contested, ethnically mixed, poor and violent city, is achieved via the ideology of Mediterranean authenticity. Thus the project is tailored to satisfy the fantasies of investors and residents who would like to live in a Mediterranean, but practically Arab-free, city.

AJ: Let’s explore neoliberalism as a source of unity and ‘creative marginality’. You discuss neoliberalism as a common threat to working class Jews and Palestinians and as causing the formation of new agencies and even a ‘search for a shared future framed in cosmopolitan, transregional, and post national terms’. Can you tell me more about these trends in Jaffa, and how significant you think they are today and could be in the future?

Also, the case of Anna Loulou and Artivism is fascinating. The case studies bring the theory to life in the book. Can we talk about one case study – the Anna Loulou bar and the ‘artivists’ who emerged from that scene, and who you call ‘the city’s most utopian but also most daring imagining subjects’? Also, I thought the writing here was noir-ish in places, like Dashiel Hammett – did you deliberately mix different styles of writing to take the reader closer to the action?

DM: Neoliberalism however is a double-edged process and along with gated communities and social enclaving came a host of urban actors who transformed the city. In fact we can trace the origins of the radical alternative cultural scene and Jaffa’s creative marginality back to the October 2000 events. In their aftermath the very marking of Jaffa as a space of violent contestation and political mobilisation further attracted various groups that had already expressed interest in Jewish-Arab cooperation through actual residence in the city, including hippie communes yearning for Mediterranean and multicultural exoticism (which have settled in Jaffa since the 1990s); individual leftists coming for ideological reasons to implement co-existence on the ground; binational youth communes; and Jewish-Arab mixed couples who cannot find their place in Tel-Aviv. The October 2000 events also attracted political Palestinian-Israeli groups that are directly engaged with conflict-related activism, such as Anarchists Against the Wall, Re`ut-Sadaqa (‘Friendship’), Ta`ayush or Tarabut (‘Jewish-Arab Partnership’), and the Zochrot (‘Remembering’) Association. While these diverse populations followed different paths, they all share a common fascination with the potential for meaning and purpose the contested city has to offer, either through political activism or individual self-searching.

Led by a general sense of frustration vis-à-vis the political stalemate, new initiatives and actors came to the fore. This is also the background for the coming together of Jewish and Palestinian activists who chose in 2011 to fight together for social justice inspired by the Arab Spring. While Palestinian activism in Jaffa has been well established – notably with the ongoing activities of the Rabita (the League for the Jaffa Arabs) from the late 1970s and the more recent Darna (Popular Committee for Land and Housing) established in 2007 – new Jewish activists have become increasingly visible. A mirror image of right-wing settlers’ new interest in mixed towns, left-leaning Jews have become involved in anti-gentrification activism while at the same time being part of the city’s gentrification. I like to call them ‘gentrifiers against gentrification’ or ‘radical gentrifiers’. In the process they are rebranding Jaffa as an alternative cultural space. Some deliberately chose to ‘live in the open wound’ as one gentrifier put it, mobilising memory and trauma as an expressive means for political art.

One of the important outcomes of the October 2000 events was the founding of the Yafa Café – the first bookstore in Jaffa since 1948 to specialise in books in Arabic. Led by Dina Lee, a Jewish gentrifier, and her Palestinian business partner Michel Rahib, Yafa Café paved the way for other cultural establishment that blend business, leisure, and politics to reclaim Palestinian cultural space. Cafés and clubs such as the ‘vegan-friendly’ Abu Dhabi-Kaymak Café, the hip cosmopolitan Anna Loulou Bar, and the Palestinian Café Salma point to the unintended outcomes of conflict and profit-oriented gentrification. Other attempts, such as Harakeh Fawreyeh (Immediate Action), complicate this nexus even further by channelling cultural and leisurely activities directly into political action.

Slogan of resistance: ‘Gentrification is economic transfer’. Photo by Yudit Ilany, 2012.

Slogan of resistance: ‘Gentrification is economic transfer’. Photo by Yudit Ilany, 2012.

Among these initiatives the most fascinating and successful one is Anna Loulou Bar – a gay-friendly, binational hangout now owned by a group of Jewish and Palestinian entrepreneurs. Positioning itself at the radical fringe of the Tel-Aviv culture scene it made virtue out of reality and merged politics with leisure and culture. Rather than shy away from politics as most bars and clubs do, the key to its success is the fusing together of the political with the eros and sexuality of nightlife. Thus you would find Arab and Jewish hipsters drinking and dancing to the tunes of Palestinian nationalist songs. But these are no ordinary hipsters – they are political hipsters who can consume city-life while debating and imagining a post-national or binational future for Jaffa and for themselves.

In telling their story I have always tried to follow the actors as accurately as possible. I rarely think of my work in stylistic terms but you might be right. Jaffa is a noir city full of anti-heroes, villains and dreamers. Its history and sociology may seem nihilistic at times, but it is always existential. These tensions make for a good story but this story is real. I might be a hardboiled ethnographer to follow Hammett but I’m no cynic.

Part 7: Futures

AJ: You end the book with this thought: ‘Israelis and Palestinians alike will have to come to terms with their mutual interdependency and relationality.’ Are you optimistic about the future?

DM: Despite my incurable optimistic inclinations I became ultimately a pessoptimist, to invoke Haifa’s native writer Emile Habibi. Beyond simple naiveté, the current desperation and blind jadedness I’m trying to look into the future. Unless the Israeli government decides to deport the Palestinian citizens of Israel, apartheid is not a viable option for the long run. With no other cards on the table acknowledging the inevitability of a shared future is already a major step forward.

AJ: You argue, ‘A wise and thoughtful integration of refugees can transform them, within a generation or two, into new European citizens, saving the continent from a prolonged demographic drought that could lead to its demise.’ What lessons – negative or positive – can Europe learn from Jaffa, in this regard?

DM: In the summer of 2015 I witnessed the influx of refugees and migrants from the Middle East to Europe as they were trapped in the Budapest Keleti train station. By pure serendipity I became involved in a research project that follows the migrants’ trajectory across the Balkan Route. Together with two fellow anthropologists we documented the reaction of the Hungarian state and civil society to the presence of refugees in terms of horizontal and vertical solidarity. This topic deserves a separate conversation of its own but what I found striking – beyond the debate on human rights – is the great lengths migrants went to in their search for livelihood and dignity. Instead they were rejected as aliens, locked in camps and eventually led by the police to the border. Now we are facing a similar process on a much larger scale with Italy, Spain, Portugal and others repeating the same mistake. I call this the Hungarianisation of Europe. But the statistics are clear – continental Europe is heading slowly but surely for a demographic disaster. With an average fertility rate of 1.55 the EU is moving closer to being a gerontocratic society. This requires a major rethinking of questions of alterity, integration and multiculturalism. Ethnic mixing touches on sociology’s basic question: how can strangers live together? That is the main question on a global scale, in view of the refugee crisis in Europe, the so-called American melting pot and in ethnocratic states, such as in Israel.

Part 8: Critical Receptions

AJ: How has the book been received in Israel?

DM: The book was very well received in Israel and abroad. Recently it has been named finalist for the Jordan Schnitzer book award by the Association for Jewish Studies. But more importantly it culminates a personal and intellectual obsession with Jaffa that has lasted for most than half of my life, so it feels good to put that behind me or at least to see it materialise in the form of a book. The drama that is Jaffa still goes on ever more intensely but the story I wanted to tell is there for the reader to engage.

AJ: What are you working on now?

DM: While for most of my career I was invested in understanding the social worlds of the Palestinian minority and the Jewish majority in Israel, but I recently started a new project on the Jewish revival movements in Europe. Changing the perspective and looking at Jews now from the position of a vulnerable minority in cities like Budapest, Berlin and Krakow is eye opening. It allows me to reflect on the predicament of racialised minorities in Europe, the Middle East and beyond. I position the presence of Jews in relation to Europe’s two other alterities: the Roma and the refugees. Thus for instance, looking at the reaction of Jewish diaspora communities to the refugee crisis provides a profound insight on the historical Jewish struggle to balance cosmopolitan aspirations and existential fears of dissolution.

[1] Jaffa Shared and Shattered has been named a finalist in the Social Science, Anthropology, and Folklore category of the 2016 Jordan Schnitzer Book Awards. The Schnitzer award was established in 2008 by the Association for Jewish Studies. In naming the work as a finalist, the award committee wrote the following commendation:

‘Much like the city at the heart of this study, Daniel Monterescu’s Jaffa Shared and Shattered resists simple definition. In one sense, this groundbreaking work uses urban ethnography to treat the experiences unfolding in Jaffa as a microcosm for revealing the contradictions of Israeli-Palestinian relations. The book reveals that Jaffa, with its many layers and intersecting narratives, serves as a synecdoche for Israel itself. In another sense, it uses Jaffa as a particularly well-suited case study for shedding light on some of the most fundamental dynamics in cities around the world today. It is not only in Jaffa that diverse groups of citizens, sometimes united and sometimes divided by different cultural and class interests, align themselves with or against private developers and municipal governments to stake their claim in creating their city as they want it to be. But it is in Jaffa that such dynamics – tinged by Jewish and Palestinian dreams, fears, memories, visions and ideologies – make their inherent stakes all the more evident. It takes a skilled ethnographer to treat this subject with the depth, nuance, and sensitivity it is due, and Monterescu rises to the challenge.

An ambitious and strikingly original book on an important subject, Jaffa Shared and Shattered is one of the rare works that brings Urban Studies and Jewish Studies together. Its broad scope ranges widely across times and topics. At the broadest political level of nationalist ideologies, Monterescu considers Jaffa’s place historically in Israeli and Palestinian nationalisms, but he complicates this by delving into the ways that Israeli and Palestinian residents alike resist their own communities’ official narratives. As he focuses in on the local intersections of politics, economics, and community-building, he trains his ethnographic lenses on crucial forces shaping Jaffa today as a neoliberal city: architects, urban planners, private developers, real estate agents and more. He reads the graffiti on the walls, and draws meaning out of the advertisements and protest posters on the new fashionably neo-Orientialist gated communities. All of this to reveal Jaffa in ways that it has never been presented before.’