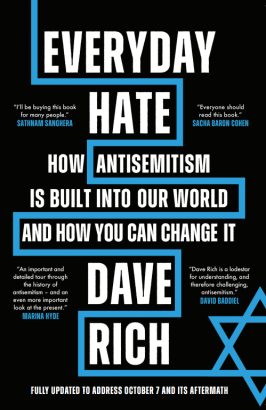

This is the preface of Everyday Hate by Dave Rich, published by Biteback.

On the morning of 7 October 2023, a year after I wrote the original introduction to this book, around 3,000 Hamas fighters poured through the border between Gaza and Israel and embarked on a murderous rampage, killing around 1,200 Israeli Jews, Arabs and foreign workers. There were more Jews slain on that day than on any other single day since the Holocaust. It wasn’t just the number of people killed that was so shocking but the method: the merciless, systematic slaughter of unarmed civilians; torture; rape; arson; ravers at a music festival chased through fields like prey; old and young, men and women, babies and Holocaust survivors captured as spoils of war. It was a shattering blow, a catastrophe not just for Israelis but for Jews around the world. Israel replied with intense bombardment of targets in Gaza followed by a land invasion that, as I write this preface in March 2024, is still ongoing and is estimated to have cost around 30,000 lives, mostly civilians. In both Israel and Gaza, the violence and death, destruction of property and displacement of innocents, is on a cataclysmic scale not seen for decades in this seemingly endless conflict.

This book is not about that war. It is an account of anti-Jewish hatred today and throughout history; of why and how this ancient prejudice still has such purchase in the modern world. It will not explain why there is conflict in Israel and Gaza or what should be done about it. Instead, this book will tell you what happened next, and why: a tsunami of antisemitism that left many Jews fearing for their futures. Across the globe, synagogues were burned, Jews attacked, and all the old antisemitic myths and libels flooded back onto our streets and across social media. In London, police reported that anti-Jewish hate crimes were running at twelve times the normal numbers. In the United States, FBI Director Christopher Wray said the threat to the Jewish community was reaching ‘historic levels’, with 60 per cent of all religious hate crimes targeting Jews. Much of this hatred was expressed in language that blurred attacks on Jews with the passions that seethe over Israel and Palestine. It is said that antisemitism is a very light sleeper, and the weeks and months following that bloody October morning showed just how easily it is awoken. It was as if everything I had written about in this book had come alive, and I knew I had to write about it once again.

This hatred and harassment of Jews occurred alongside a global wave of activism for the Palestinian cause that played out on a vast scale. The largest protest in the UK saw an estimated 300,000 people marching through central London; more people on one demonstration than there are Jews in the entire country. Week after week, huge numbers went out onto the streets to protest in a way that never happens for any other overseas conflict. Most protesters did not say or do anything antisemitic, but on every march there were some carrying antisemitic placards, or comparing Israel to Nazi Germany, or declaring their support for Hamas, even after the massacre. Some of the most popular chants and slogans implied, if you were that way inclined, support for a violent uprising that would see the end of Israel for good. Media stories about the conflict in Israel and Gaza, the protests over it, and the rise in antisemitism, dominated the headlines for months. And amidst all of this, Jews around the world tried to piece back together their fragile sense of belonging and stability of mind that had crumbled on 7 October 2023.

As these phenomena ran in parallel, disputes over whether they are connected – some arguing that anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism are the same thing, others that they are not linked at all – raged just as fiercely. Every word, photograph, social media post and statistic was endlessly challenged. Depending on your point of view, you may already feel uneasy with how I have described the events in this preface, but I hope that doesn’t put you off. Raising the alarm about antisemitism is not the same as defending Israel; it should be possible to do the former without it being mistaken for the latter. Surely, whatever our views of Israel and Palestine, we can all agree on that.

Nor is this just an academic argument: it has real-world consequences. Disagreements over when anti-Israel invective becomes antisemitic played a role, directly or indirectly, in the resignations of a British Home Secretary and the presidents of Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania. In a way, it determined the outcome of a parliamentary by-election in Rochdale. According to British counterterrorism police, the incitement and extremism posted online was on a scale they had never seen before – even following recent terrorist attacks in the UK. As communities became more divided and politics polarised around this issue, it was a reminder that the state of antisemitism has often been an indicator of the health of democracy. This is a danger none of us can ignore.

There is a vital need to disentangle the politics from the prejudice, the legitimate from the hateful. The anti-Jewish ideas, language and imagery that came to the fore after 7 October 2023 were not invented in those febrile days and weeks: they were generated long ago, often in places far from Israel or Gaza, and have been seen countless times before. Antisemitic placards and social media memes are just the latest reinvention of centuries-old myths and libels that are woven into the fabric of our civilisation, an intrinsic and often unrecognised feature of the world we all live in. How this has come about, why it keeps coming back and what we can do about it are the questions I originally set out to answer in this book. This felt essential when I wrote it a little over a year ago. It is now more urgent than ever.