When Fathom launched we promised there would likely be a piece in every issue with which you would disagree. Though our centre of gravity remains the two-state paradigm, our ambition was always to make available the full breadth of debate in Israeli society. And so we have published voices from the ‘left’—Palestinian writers, the lawyer Michael Sfard, and B’tselem and Settlement Watch leaders (and have the scars for doing so). But we have also published voices from the ‘right’—the Kohelet Forum, the Yesha Council, and Regavim. And, of course, we have (mostly) platformed everyone in between. In response to the current furore in Israel, Fathom has published articulate voices for and against the proposed judicial reform, as well as those proposing a compromise, and we will continue to do so in the weeks ahead. In a polarised culture increasingly keen to wield institutional power to cancel and to exclude an ever-wider range of voices from the ‘community of the good’, Fathom will continue to respect the precious values of intellectual and political diversity, even if we end up being the last pluralist journal standing. Debate can’t begin, compromise can’t find its bearings, until each knows what the other side thinks. If both sides fight to silence the other then, be warned, we could yet end up with something far worse than an intellectual desert. In that spirit, we publish Gabriel Noah Brahm’s fascinating interview with one of Israel’s leading intellectuals and creative writers, Gadi Taub. Once of the left, now of the right, he discusses his political journey, defends the need for judicial reform, explores the phenomenon of what he calls ‘postjournalism’, and discusses the arguments of his 2019 bestselling book, soon to be published in English as Global Elites and National Citizens: the Rise of Anti-Democratic Liberalism in Israel, the U.S. and the West. Responses, as ever, are welcome. (Alan Johnson, Editor of Fathom)

Introduction by Gabriel Noah Brahm

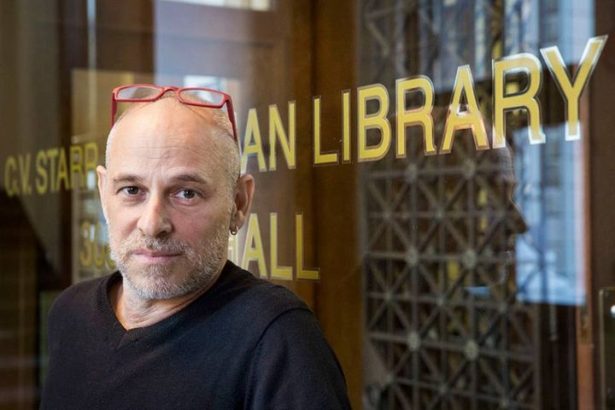

Senior Lecturer in the School of Public Policy and the Department of Communications at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Dr. Gadi Taub is an Israeli historian, novelist, screenwriter, political commentator and influencer of wide repute, ubiquitous on television, social media, podcasts and in print.

Once a man of the left, Taub says he is ‘one of those liberals who got mugged by reality’ and is now a prominent intellectual on the Israeli right and host of Israel’s leading conservative podcast, Gatekeeper (שומר סף). He recently conducted an exclusive hour-long interview with Justice Minister, Yariv Levin, who laid out the details of his proposed reform. (The interview is now available with English subtitles on the Gatekeeper channel.)

Moreover, some on the left have come to consider Taub so dangerous that his long-running column in Haaretz was terminated by its publisher, Amos Schocken, who justified the decision on the grounds that Taub’s columns were, he claimed, giving a ‘tailwind’ to a ‘coup’.

The following is a transcript, lightly edited for readability, of a recent conversation conducted at Taub’s home in the heart of Tel Aviv, not far from Allenby Street, which gave its name to the hit Israeli TV show, based on his novel, Allenby.

The Reform is Needed

Gabriel Noah Brahm: Professor Taub, you seem to have become a polarising figure these days. In any case, you’re in the eye of the storm concerning legal reform, for one thing. But you’ve also had some ups and downs with a longtime publisher of some of your more public-facing work—Israel’s leading highbrow daily, Haaretz, which seems to have ‘cancelled’ you. First of all, how are you doing? How do you handle being caught up by such a whirlwind of attention? Moreover, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the country’s future and your own prospects?

Gadi Taub: I’m optimistic, because I think Israel’s democracy is proving much more vigorous than Israel’s elites assume. Their hysteria is not a result of any danger to democracy. It stems from their fear that their hegemonic rule is at an end—which it is. Their ability to rule us from above, from the bench of the Supreme Court, is crumbling. It cannot be saved, even if they defeat the judicial reform now, which can only be done if the chaos they are trying to cause spirals out of control, causing a split in the coalition.

Look at this battle over reform and the way it is conducted. The reform itself is clearly needed. An arrangement where 15 unelected judges hold the final power of decision over any and all matters—political, legislative, economic, social, while also holding a veto over the appointment of their own associates—cannot be called democratic by any stretch. Keep in mind that on many of the most important issues of the day these 15 individuals mostly hold to the opinions of Meretz, a progressive political party that did not pass the threshold [to hold seats in the Knesset], and you’ll get the picture of just how distorted politics have become in this country.

This is only sustainable if you prevent the public from realising what’s really going on. But you can’t do that forever. ‘You can’t fool all of the people all of the time’, said Honest Abe. Israelis, educated and uneducated alike, are tired of seeing their ballots shredded by judges. And since in this country existential threats are ever close and vivid, so are reality checks. This puts progressive pipe dreams at a permanent disadvantage.

Sacked in the Morning

GNB: Can you explain your dismissal from Haaretz? Did it have anything to do with what I believe you call ‘postjournalism’? What is ‘postjournalism’?

GT: The end of a good screenplay, David Mamet once said, has to be both surprising and inevitable. I think my dismissal from Haaretz qualifies by that test. It was clear that the pluralistic pose can’t actually stand someone who is constantly attempting to expose their real mission—which is not journalism, but political activism. And so increasingly they’ve been limiting my wiggle room, occasionally censoring pieces—especially pieces that had to do with police abusing their investigative powers, such as the use of cyber weapons to illegally penetrate cellphones. The police, ever since it seemed it would help bring down Netanyahu, are largely shielded from criticism by the mainstream media.

So they tolerated me, just barely, for a long time. But now it’s the money shot, right? For the first time, the oligarchy for which Haaretz is the mouthpiece is under a serious threat from democracy. And so the fraud they are engaged in—disguising their attempt to defend their own privileges via the Supreme Court from democracy as a ‘struggle to save democracy’—has to be airtight. They can’t afford even one hole in the wall of lies through which readers might see something else. So they can’t have anyone calling their bluff.

You can see how it works by the way my dismissal transpired. It happened in two stages, which will also tell you what I mean by postjournalism, a term coined by media scholar Andrey Mir. I wrote a piece defending the reform and calling their ‘struggle to save democracy’ a sham. And then the editor of the opinion section, Alon Idan, sends me a list of fact-check style queries. From the way they were phrased it was obvious to me that he was looking for an excuse to reject the piece on account of its being false.

By coincidence that evening I had dinner at a friend of mine’s who’s a retired judge, and the other guests were two out of a handful of Israel’s leading law scholars, one a former cabinet minister. So, I raised the questions over dinner, and made notes. The next morning I sent back my answers which showed—quite decisively, I dare say—that I had my facts straight. I assumed that any paper with even a remnant of journalistic integrity will now be honor-bound to publish the piece.

Instead, they terminated my column, which basically means they did not reject my piece because it was false, but rather because it was not. Apparently, it showed a truth too dangerous for their readers to see. They admitted as much, almost literally, in their strangely ingenuous letter of termination.[i]

GNB: The well-known political commentator, Ruthie Blum, argued it’s a badge of honor, that dismissal letter, which admitted to banning you for purely political reasons—something you should be proud of and even ‘celebrate’. Are you celebrating?

GT: Oh, yes. I made sure to embarrass them wherever I was interviewed about it. And I was not alone. Leading pundits, some of whom strongly dislike my views, even some with whom I had public quarrels, protested this censorship. Haaretz publisher, Amos Schoken, however doubled down. He called my views ‘illegitimate’, no less, and said they ‘should not be heard’.

It is no small tragedy that Haaretz, which still monopolises highbrow debate in Israel, fell into the hands of an eccentric man—self-righteous and intellectually illiterate, who made it his mission to fight against the legitimacy of the very idea of a Jewish nation state—never quite admitting the mission that his pages clearly betray, especially the English edition. As Jeffrey Goldberg said to Schoken when he canceled his subscription to Haaretz: ‘When neo-Nazis email me links to Haaretz op-eds declaring Israel to be evil, I’m going to take a break, sorry’.

The paper has been a Bolshevik publication for some time, in fact, but now it saw fit, for some reason to which I am not privy, to openly admit it. Think about it. My opinions on the reform are held by more than half the public. So the opinion of the majority of Israelis is, in the view of the publisher, not just wrong, but ‘illegitimate’. Well, at least now we know full well what we are reading.

Postjournalism

GNB: So what’s ‘postjournalism’, then? What interests you about it? Why does it matter?

GT: What defines postjournalism is a change in orientation that occurred most poignantly in the liberal press: its mission is no longer informing the public but rather political activism. It’s not that press organisations did not have a political stance before, of course, it’s just that they did not give themselves license for conscious distortions, omissions and even lies—or at least these were never before considered honorable. Now they are.

GNB: How and why did this happen?

GT: It’s because the postmodern ‘woke’ combination of epistemological skepticism with moral absolutism—that is, a denial of the existence of objective facts coupled with supreme confidence in one’s political views—very easily becomes a license to lie. And this is what happened to Haaretz, which is clearly no longer a newspaper in the traditional sense. It is an instrument of political activism, a tool of indoctrination.

For example, there is now a newsletter from the deputy of the paper’s chief editor, Noa Landau, which is coordinating the demonstrations against the reform, which Haaretz then also covers. Traditional journalistic ethics would have alerted you to the fact that you cannot organise the events you are supposed to cover—not any more than it’s legitimate for the arsonist to cry ‘fire!’ But we are not dealing with anything recognisably journalistic here.

GNB: Is this something specific to Israel?

GT: No, no, not at all. It’s not just happening here: in the U.S., the New York Times acknowledged that the information on the Hunter Biden laptop was authentic a year and a half after the elections. That amounts to an almost explicit admission that it helped cover up a major story that might have hurt Joe Biden’s presidential bid. That is the opposite of what we used to think of as journalism.

Or if you look at the way Dean Baquet, then executive editor of the Times, explained to his staff what they should do in the aftermath of the Mueller Report. The Mueller Report failed to find evidence of any conspiracy between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin, and this, he said caught the paper ‘a little tiny bit flat-footed’. That should qualify as the understatement of the decade. Russian Collusion was their constant front page story for three years. But instead of simply acknowledging a journalistic failure to verify a story they were trumpeting, he seems to lament something else entirely: that the story did not achieve its desired political effect. ‘Our readers who want Donald Trump to go away suddenly thought, “Holy shit, Bob Mueller is not going to do it”’, Baquet said.

And so the conclusion is not more reliable coverage, but better activism. The paper, he explained, would ‘pivot’ to a different way of covering racism, exemplified by the ‘1619 Project’, The next move in the direction of historical revisionism, conceived as a new form of pseudo-journalistic activism. It’s all publicly available. Slate published a detailed report of the infamous Times’ ‘town hall’ in which Baquet explained all this to his staff, as if this was all legitimate in a news organisation.

GNB: But why does it matter? What’s the big deal? Can’t readers decide for themselves what to think?

GT: Not if they are being fed lies. If they’re being fed lies their opinions are divorced from political reality. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not about censoring lies. Freedom of speech should cover the right to lie—limited only by rules against slander, incitement to violence, or speech causing clear and present danger, and so on. But lies should be called out. And we should withdraw our respect from liars. Which will happen, over time. People will lose confidence in the Times, which Andrew Klavan already calls ‘a former paper’.

But here’s what I think makes the current incarnations of postjournalism so dangerous. It has not only corrupted journalistic ethics, it has also chosen a uniquely dangerous path for its activism. Journalists are supposed to be the watchdogs of democracy, by which we mean they should be able to call public attention to the abuse of power by the state.

But in our postjournalistic age, different sectors of the same elites are closing ranks, and so journalism has become the PR service of law enforcement. Or rather law enforcement has become the huge investigative arm of the press. When it comes to right-wing politicians, investigations are too easily opened, and then it seems like they do not aim at producing evidence in a quest for conviction, so much as they aim to produce leaks in the quest of intercepting politicians by hurting them at the polls.

Either way, this new intimacy between law enforcement and the press, is a serious danger to the ability of liberal democratic societies to protect civil rights. We now see this with the total collapse of the cases against Netanyahu in court, which the mainstream press is not telling us about, but that independent journalists, diligently reporting from the courtroom, have exposed.

Netanyahu’s Trial

GNB: You really think Netanyahu and his voters suffer because of postjournalism? Is it so partisan as that? He’s back in power, so how bad can it be?

GT: Look, after four rounds of elections, where Netanyahu’s fortunes seemed to be sinking, in the fifth, he emerged with a clear majority. So I think we should interpret the result as a referendum on the trial. The jury which in this case is the whole electorate, delivered a ‘not guilty’ verdict, which means enough people came to believe that Netanyahu was being framed.

To a large extent, this is because of the various independent journalists—some of them volunteers—which filled the journalistic void that postjournalism has left behind with good old fashioned reporting. While the mainstream press was ignoring cross-examinations, independent journalists who sat in court were diligently texting what was going on.

Up until the trial began the mainstream media had almost total control of the narrative. When the State Attorney was feeding them daily leaks, the defense was helpless to counter them. But once the trial began and evidence was tested by the adversarial process, the mainstream media lost their monopoly on shaping the way the story was told. Now there was a record of counterarguments which the press could ignore, but could not make go away. So it was only a question of time until the counter-narrative began to get traction.

If you look at the context of all this, then you can see how the alliance between the press and law enforcement began. It was after Netanyahu had just won a fourth term in 2015, and the left despaired of beating him at the polls, that the media started clamoring for his head and producing ‘investigative pieces’, mostly questionable, demanding the police follow up with investigations. The police quickly learned the advantages: good press, and turning a blind eye to its abuses of power.

Mugged by Reality

GNB: I’m a little surprised to hear an academic, as well as journalist, talk this way. It’s often said that you changed your politics fairly recently, and people wonder what it means. Have your politics changed? Was it a sudden thing, sparked by anything specific, or did your politics evolve? Did you leave the left or did it leave you (as President Ronald Reagan famously said of the American Democrat Party)? As I’ve heard so many put it: ‘What happened to Gadi Taub?’

GT: I guess I’m just one of those former liberals who were mugged by reality. I grew up going to Peace Now demonstrations, and feeling I belong to the enlightened few. But that was predicated on the comforting idea that it was up to us to solve the conflict with the Palestinians, if only we stop fearing change. That’s an uplifting view, which gives you an illusion of control.

So we stopped fearing change, and change came. It exploded in our face. Literally.

I live in Tel Aviv, which is geographically fairly small. When buses were exploding, I could usually hear the booms at home, or at the Shenkin café where I used to sit with my laptop. So when you heard a loud concussion followed by wailing sirens, you knew that another terror attack had occurred.

Gradually, one had to admit that Oslo wasn’t working. It wasn’t building trust, it was eroding it. And if you were halfway honest with yourself, you’d begin to question Yasser Arafat’s intentions, despite the systematic attempt by literally the whole press corps to suppress information about his direct involvement in terror. There was no social media back then, so they could.

So, I too reached the same conclusion that Ehud Barak, for whom I voted in 1999, did. Namely, that rather than drag it on and erode trust between the two peoples even further, we should move directly to the core issues and cut the Gordian Knot where the middle was assumed to be. Give the Palestinians almost the whole of Judea and Samaria, with supplemental land swaps for such settlements as would be too hard to uproot, no ‘return’ to Israel proper by the descendants of the 1948 refugees, and Jerusalem partitioned, with international control—or some form of dual sovereignty—over the holy sites.

But then Arafat said ‘no’. And he said so poignantly, because he would not give up the so called ‘right of return’ which is suicide for Israel to accept. Absorbing a large portion of the Palestinian diaspora (5 million people) in Israel would mean the logic of partition would be completely undermined. Professor Alexander Yakobson from the Hebrew University has called this ‘the two states for two people on average solution’: one and a half for them, and half for us.

So then a large number of Israelis, myself included, turned to unilateralism. We said, ok, there is no partner for peace on their side, but we don’t want a binational state, so let’s partition the land anyway, and leave it to them to manage their side in whichever way they see fit, until they come to their senses and opt for peace. Ariel Sharon defeated the Labor Party which ran on that platform, and then adopted their platform—unilateral withdrawal from Gaza.

But rockets from Gaza didn’t stop, as we hoped they would, and no partner for peace emerged. Instead, Hamas won the elections and then slaughtered all the Fatah operatives that stayed in Gaza. That is because Hamas does not see Gaza as the Palestinian homeland. Israel itself is their idea of what they’re entitled to, and so when they say ‘occupation’ they generally don’t mean the military rule of the West Bank—they mean any sovereign Jewish presence in the Land of Israel. Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf, both moderate leftists, explain this in their important book, The War of Return: How Western Indulgence of the Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed the Path to Peace.

Still, we were hoping to impose partition even on a recalcitrant Palestinian population. But then came the two final blows: the Second Lebanon War, in 2006 showed that projectiles in sufficient numbers can paralyse life in Israel, as they did for the north of the country for much of the duration of the war. If the huge mountain range of Judea and Samaria would turn into a Gaza-like Hamastan, on a grander scale, then the seaboard, which is the heart of Israel—in terms of industry, economy, population and strategic assets—would be at the mercy of anyone with a small rocket launcher, and our international airport at the mercy of even anyone with a light semi-automatic, since the approach to Ben Gurion Airport, depending on wind direction, is from over Samaria. Remember, this is a nine mile wide strip from the beach to the foothills of Samaria at the narrowest point. It’s all tiny. So, we realised we could not afford to have the mountain range fall into hostile hands.

And then came the so-called Arab Spring, with nation states collapsing all around us. It demonstrated that nationalism is not a stable principle of political order in the Arab world, which cast serious doubts over the viability of the very idea of a Palestinian nation-state. Here we are in a shifting sea of political lava with no stable principle of order—not Pan-Arabism, not Arab Socialism, not Political Islam, and not Nationalism—so we cannot at any cost allow territorial continuity from Teheran right up to Ben Gurion airport.

That was it for me. There’s no way we’re giving up the Jordan Valley and the mountain range, a formidable geographic barrier between us and the ever-shifting shapes of violent Jihad.

GNB: So where does all this leave the ‘two state solution’?

GT: The two-state solution is no longer relevant. Still the best we can hope for is not that far from Rabin’s original vision: extend Israel’s sovereignty to the Jordan Valley while leaving open an option for what he called a ‘state minus’—that is, minus control of the borders, airspace, and without an army—or what Begin would have called ‘autonomy plus’. The Palestinians should be able to run their local affairs, subject to security considerations, in areas A and B.

Global Elites and National Citizens

GNB: You published a book in 2020 in Hebrew (which I understand is being translated to English), called ניידים ונייחים—or roughly Mobile and Stationary. First of all, how would you yourself, perhaps more elegantly, translate the title, and what does it refer to? What prompted you to write such a book at the time?

GT: The English translation, which Peter Berkowitz of the Hoover Institution did, will most probably be called Global Elites and National Citizens: the Rise of Anti-Democratic Liberalism in Israel, the U.S. and the West. It started with a piece in Haaretz where I toyed with an idea that I quickly discovered had been better expressed by David Goodhart, in his book, The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics.

What he calls the ‘Anywheres’ and ‘Somewheres’, I called the mobile and sedentary because in Hebrew the two words sound almost the same: nayadim and nayahim. But my main argument is far from Goodhart’s. It became increasingly clear to me that there is something wrong with our political taxonomy which assumes that nationalism and human rights are at odds, because I have been writing quite a bit on the necessity, or something close to necessity, of nationalism to the democratic form of government—since there needs to be some kind of bond that ties a political community together if we are to assume that universal suffrage would be used with the intention of promoting some kind of common good, and not just for a narrowly defined self- or group-interest.

So assuming that we have nationalism on the one hand and democracy on the other, as liberal elites tend to, was clearly wrong. But so is the other side of this, which assumes automatically that democracy is on the side of the party of universal human rights.

GNB: Are the two, democracy and human rights, necessarily at odds? Surely not!

GT: They shouldn’t be, but they can be. They should be connected, since the single effective way we know to protect our liberty, property, and other basic rights, is universal suffrage, the consent of the governed. In this sense, the right to vote and be elected—i.e. citizen sovereignty—is the anchor of all other rights. It is also a crucial aspect of our liberty—our ability to contribute to the shaping of our common destiny. Yet, the idea of human rights can be—and in fact now often is—turned against democracy.

GNB: So then how does that ‘turning against’ citizens’ sovereignty work, in your view? Sounds troubling.

GT: If human rights are used to undermine nation states, or to subject them to an authority higher than the consent of the governed, then they necessarily undermine democracy.

Increasingly, this is how human rights organisations do it. And so do globalist elites who wish to ‘transcend’ nationalism in the name of universally applicable rights. They rarely announce it, but transcending nationalism is also transcending democracy, because if you subordinate democratic nation states to international organisations, international treaties, international economic forums, or international courts, then you subject citizens to governments they did not choose.

GNB: This chimes with much of what ‘populists’ have been saying. Are you a populist?

GT: These views have been very clearly articulated, by a scholar who is, in my view, the most unjustly underrated in the field of political philosophy. John Fonte. I discovered I was working in a tradition founded by Fonte when I came to present the theme of my book at Washington’s Hudson Institute, where John is a senior fellow. I was invited there by Michael Doran, who besides his brilliant foreign policy analyses also speaks fluent Hebrew. So he knew about the book and invited me to speak. And after my talk this soft-spoken older guy approached me with a folder that contained two of his pieces. I thanked him politely and put them in my bag. When you lecture there are often people who want you to read their work. But this time was different. Later that night, when I looked at these pieces, I was blown away.

His perspective was American, and his terms were different, but most of what he said has transpired exactly as he said it would in Israel too. He predicted that the major struggle within the West would no longer be between capitalism and socialism, or anything that the old terms left and right can capture. It would be a struggle between ‘global governance’ and ‘democratic sovereignty’. This is exactly the right framework, within which you can place my analysis of Israel as a case study for the struggle between globalist elites, which are increasingly antidemocratic, and the majority of citizens, who have their livelihood, language, culture, identity and political power all rooted in the nation-state. Populism is supposed to be a derogatory term, coined by globalist elites, to describe what we should actually respect: democratic national self-determination.

GNB: What has been your book’s impact? How was it received initially? And how is it looked at now? Has it turned out to be, as some are saying, prophetic of what we’re seeing going on in Israel today, almost three years after you wrote it?

GT: The book was a bestseller here. The very hostile review in Haaretz predicted that it would become the manifesto of the Israeli right, which I don’t think it did, but it made an impact. It was ignored by academia, which is no surprise at all, since academia is a bastion of globalism, and one of the least diverse institutions in our society. I mean diversity of opinion, not identity. In fact, the superficial diversity of what passes for identity these days, is a mask for imposed ideological uniformity. But recently I feel vindicated.

It has become fashionable among the member of the social class which is now fighting against the judicial reform to threaten to leave the country. This is exactly what I tried to articulate with the label ‘mobile’: a class that aspires to transcend provincialism by identifying with its counterparts in other countries more strongly than with their own nation. Of course, few things are more provincial than the yearning to transcend your province, which now is the nation-state.

But I also have second thoughts about parts of the argument. The mobile classes are less mobile than they think—or than I thought they were. They imagine themselves to be cosmopolitan, but rootedness is often stronger than we believe it is. We assume we are not tied down to a place and a culture, until we test our beliefs by trying to live elsewhere. As a beautiful song by Israeli musician Shlomo Yidov, who made aliya from Argentina once put it: ‘I think and write in Hebrew with no difficulty / And I love to love you exclusively in Hebrew / It’s a beautiful language, and I will have no other / But at night, at night, I still dream in Spanish’.

I think national identity is deeper than we commonly assume, and that it is at the heart of political self-determination. That is, when we are left at liberty to create our democratic communities, national self-determination seems to be the high road which most peoples choose.

It is, as I said, also the bedrock of healthy democracy. And the only known way to keep it from turning dangerous is to allow it to flourish in a liberal democratic framework. Try to suppress it, and you’ll have to deal with violence—which of course you sometimes have to, as the failed peace process has shown. If our neighbors would have channeled their national sentiments into democratic self-determination, we’d have had for some time already two nation-states, living side by side in peace. Unfortunately, this is not in the cards, for the foreseeable future.

[1] Taub is alluding to his severance notice, translated into English by Ruthie Bloom and published in her Jerusalem Post column. The notice sent by Haaretz began, ‘I am forced to write this mail after many years of joint work, and alongside the difficulty of publishing your articles, which were unpleasant to many Haaretz readers [but which I] thought were making an important contribution to freedom of expression and the possibility of being exposed to other and different views’. began the digital missive by his editor, explaining the ouster. Nevertheless, the letter went on, ‘two things happened recently that changed the paper’s stance on your pieces. One is the change of government, accompanied by an aggressive and immediate attack on Israeli democracy as we, at Haaretz, perceive it. The desire to weaken the judicial system through extreme, unilateral and unrestrained measures compel us, too, as a media outlet, to defend against what is perceived among us as a coup d’etat. In this respect, we find it very difficult to reconcile the dissonance: on the one hand, to be the spearhead against this coup, and simultaneously to publish articles that provide a tailwind to that very coup. In terms of defensive democracy, we believe that now is the time to go on the defensive’.

Very interesting interview, I wonder, was the opinion piece published elsewhere?

I ended my Haaretz subscription last month for the same reason I stopped reading the Guardian, Brexit was the final straw regarding the Guardian, but read on and see if Haaretz are guilty of the same kind of reporting.

I voted for Brexit reluctantly, I thought long and hard about it, had very good reasons, and have many times had long, sensible discussions with Remain voters, and we both come away with an understanding of each others point of view.

I started reading the Guardian in the run up to the referendum, it was a frustrating experience, too often their headlines and opinion pieces were implying the question on the ballot paper was about the economy, rather than everything involved with being in the EU, including Freedom of Movement.

Vote happened, result announced, then the Guardian just went crazy, absolute disbelief that the majority could vote to leave the EU.

Then it started, repeatedly mentioning that the least educated voted for Brexit, explaining how many Brexit voters had fell for ‘the lies on the side of the bus’, explaining how right wing newspapers and politicians had lied, and how part of the electorate had believed those lies, they continually implied that Brexit voters, Trump voters, and Climate deniers were one and the same.

Then came the “they didn’t know what they were voting for” line to try to get a ‘confirmation’ vote (re-run the referendum), they were so convinced they’s win, they had no idea how insulting that line was to the working class (who were the bulk of the Brexit vote).

They carried on getting expert after expert to tell their readership how bad Brexit would be for the economy, it was relentless and never ending, then they started reporting their repeated opinions as fact.

I finally had enough, I found it so frustrating that a large percentage of their readership have no idea why some very sensible and thoughtful Brexit voters voted the way they did, and the irony, it was predominantly left leaning working class voters who voted for Brexit.

Absolutely wonderful; such a wealth of ideas and clarity.

I don’t see anyone in the intellectual field today who comes close to rebutting any of his arguments

Which raises the question why is Gadi Taub not embraced by more “truth” seekers?

I think the answer was once coined by a French intellectual more than 50 years ago. French intellectual life then pitted Jean-Paul Sartre against Raymon Aron the latter was a keen political realist who was proven right more than once. Yet the saying goes that people preferred to be wrong with Sartre rather than right with Aron.

Gadi Taub says a very “sad” truth which most people will not want to believe!