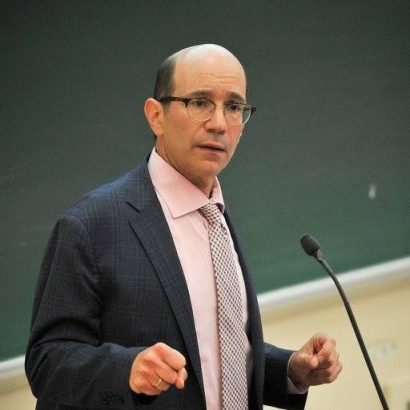

Professor Gil Troy’s The Zionist Ideas: Visions for the Jewish Homeland―Then, Now, Tomorrow is a compilation of over 170 different Zionist visionaries. In this interview with Fathom Deputy Editor Calev Ben-Dor, Troy discusses the composition of the book, the challenges Israel faces today, and his argument that nationalism should be a key component of liberal democracies in the 21st Century. Download a PDF version here.

Calev Ben-Dor: In your book, you divide the sections up into three periods – pioneers, builders, torchbearers – and into six categories – political Zionism, labour Zionism, revisionist Zionism, religious Zionism, cultural Zionism, and diaspora Zionism. What made you divide up the story of Zionism in that way?

Gil Troy: The basis of the three-part division was from a bestselling book (whose sales I would hope to replicate), the Bible. It’s comprised of Torah, Neviim (prophets) and Ketuvim (writings). The first part of Zionist Ideas covers the foundation of Zionism and its core ideas, and includes thinkers Arthur Hertzberg featured in his original anthology plus new additions: women, Mizrachim, and some poetry. But fundamentally the first section includes the crazy, visionary, conversation that started with the question of what is the ‘Jewish problem’? Some say it’s anti-Semitism, others that it’s assimilation. Remember, Zionism was very marginal at a time when most of Jewry – to the extent that it was on the move – was moving to the US rather than to Palestine/Eretz Yisrael. The first part – the Zionist ‘Torah’ – takes the story to 1948. Until then the conversations are in many ways still theoretical and aspirational. After the state’s establishment, many people say ‘that’s it, that’s the end of Zionism’ as they feel it’s no longer necessary. After all, Zionism was the movement to establish a Jewish state in our homeland.

One of the core themes of the book is the question of what nationalism – and particularly liberal nationalism – is in the 21st Century. I have my bias and understanding as a professor of American history. I believe nationalism has to be dynamic and visionary, especially Jewish nationalism i.e. Zionism. The second part of the book covers the period from 1948 until 2000 when the ‘prophets’ take the original ideas and apply them. This section includes David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, Shulamit Aloni, Menachem Begin, and voices like Yitz and Blu Greenberg, and Elie Wiesel in the US as well as Natan Sharansky.

The third part of the book covers the debates and visions of today, among those I call ‘the torchbearers’. We are the heirs to this amazing tradition of pioneers and prophets. Now, we are the torchbearers with an obligation, a challenge and an opportunity: to do something positive with this amazing legacy of ours. That was the idea behind the three-part harmony.

Nationalism – as Ben-Gurion answered a cynical reporter who asked whether Israel had achieved its ideals – will always be infused by ‘not-yet’. That ‘not yet-ism’ is a beautiful answer because it says three things. First, we are striving (because that is the nature of liberal democracy). Second, that we are never going to achieve perfection (because human beings are by nature imperfect). Third, nevertheless, we always must keep pushing on. Nationalism is at its best when it tries to be transcendent, tapping into core ideas and values. I believe that we can only be better by working together with those supreme values, otherwise we spin off into selfishness and solitude.

CB-D: In different ways, both President Barak Obama and President Donald Trump have downplayed American exceptionalism, upsetting a lot of people. Many Israelis also feel that sense of exceptionalism.

GT: I think the feeling of ‘exceptionalism’ is in the DNA of all liberal democracies. What is any liberal democracy without nationalism, without that sense that we are trying to work together in this place to make our lives better and the world a better place? I think that it’s a given in all forms of what I’d call democratic nationalism.

But yes, I do feel the US and Israel are unique because, more than other liberal democracies, they are based on an idea, and that makes them more ambitious. The US has been trying to be a ‘Novus ordo seclorum,’ a new world order, and Israel is trying in the words of Theodor Herzl – who is often wrongly identified as just a garrison Zionist – as being an Altneuland (an old-new land). They both had this belief that by establishing an ideal place they would make the whole world a better place. That idea ties into notions of chosenness and of tikkun olam, of particularism and of universalism, and also exceptionalism.

The duality in nationalism

CB-D: You’re also saying that there’s another side to the coin, which is the frustration when that doesn’t happen.

GT: Let’s acknowledge that in the 1940s there was no people who understood better than the Jewish people how murderous and evil nationalism could be. But by 1948 with the state’s establishment, there was no other people who understood better than the Jewish people how inspiring and empowering liberal nationalism could be. So I start with the acknowledgement that nationalism itself – and this is a counter-cultural argument these days – is a neutral tool. It can be good, it can be bad, and Jews understand this. That’s one part of the duality. This is for me the central ideological fight of our time: to make nationalism a constructive force in this age of right-wing and left-wing demagoguery. Post-modernists say that all nationalisms are evil (except for those three or four they like, including Palestinian nationalism, which they consider holy). The ultra-right wing says that only their nationalism is holy but everyone else’s is evil.

Our very ambitiousness should bring out the best in us, to push us to do better. But it sometimes brings out the worst in us. Inevitably, this means that we are always going to be disappointed. And when disappointment spins off into fear, despair and resignation, it can be dangerous.

I want us to be an aspirational democracy. The essay in the book by Tal Becker talks of ‘aspirational Zionism’. I want us to play with those tensions, to become ‘Fitzgeraldean’ [Scott F. Fitzgerald, the great American novelist, said that the mark of true intelligence is to hold two competing ideas in your head at once.] Most of us have gone down the path of one idea or another – we believe we have to choose between being proudly nationalistic or deeply democratic. This all or nothing-ism is on the rise in the world today that is extreme, anti-democratic, illiberal but also, anti-the-true-constructive nationalism because there has to be this constant balance of competition. Zionism, Americanism, liberal nationalism, benefit from the internal tension and the resulting synthesis.

Not-yet-ism and dealing with disappointment

CB-D: Amos Oz argues that ‘Israel was born not out of one but many dreams, including several conflicting, contradicting and mutually exclusive dreams’. Zionism was always going to be a disappointment because that is the nature of dreams, let alone mutually contradictory dreams! I think the challenge is where one goes from the realisation.

GT: There is an inherent tension, perhaps in Zionism even more than in any other nationalism, between the intense desire to be normal and the inability to be normal. There was a promise of normalcy in Zionism that hasn’t been fulfilled in many ways. ‘Normalcy’ meant an escape from anti-Semitism, but also being able to breathe easy and fit in, in contrast to our experience in Europe. Of course, I’ve never found a Zionist who has been able to settle for just being normal. There is also this desire to stand for something, to reach for something.

CB-D: That relates to something Isaiah Berlin once said, that ‘for our purposes, for Jews, Albania is a step forward’.

GT: But being ‘just normal’ never worked. It was never a serious strain in Zionism. Oz wrote a beautiful essay on homeland which I included in the book. He says that there are those people who believe in the promised land, but he never believed in the promise nor the promiser, so his Zionism is hard and complicated. Oz accepts that there is a gap between our lovely ideals and the messy realities. But he wants to keep striving, he won’t settle for a normal, boring, meaningless existence. Similarly, there’s a great essay by Leonard Fein – also in the book – in which he talks about the tensions between fitting in and standing out, between security and morality, and he says he’d rather be a part of a people who opt for nervous breakdown because they’re trying to balance all these things rather than simply opt for one of the two poles. That’s an appreciation of complexity which I think is often missing today.

CB-D: Oz also talked – in his book In the Land of Israel when he visits Bet-El in the West Bank – about the danger of ‘now-ism – i.e. wanting perfection now and if you can’t get it then to hell with everything. Your ‘not-yet-ism’ is an interesting counter to that approach. To have these dreams and know we are on the way to them but we are not there yet is an authentic Jewish approach, I think. I’d be very interested hear you expand on ‘not-yet-ism’.

I think we’re having a different form of a nervous breakdown today as we veer to the Left and Right extremes. ‘Not-yet-ism’ is saying we need to see the gap between our ideals, our dreams and the messy realities, acknowledging and recognising this as the human condition. But secondly, we need to stop and look around at the miracles of the state – the miracle of three million Jews coming from all these communities as refugees and becoming citizens. Look not just at the ‘Start-up Nation,’ but look at the day-to-day nation; the fact that we’ve created this democracy from people who didn’t come from democratic cultures, (although they came from the Jewish culture which I argue is a democratic culture).

The Israel-diaspora relationship

One of my frustrations about the conversation going on in the Jewish diaspora is that even most Jews receive their day-to-day picture of Israel from the pipeline of media articles (sometimes just of one political angle). Those on the right read ‘their’ sources on Gaza and BDS, and those on the left read ‘their’ sources on the Nation-State Law, or ‘occupation’. People are whipped up into a kind of frenzy and we get two kinds of apocalyptic thinking, claim that democracy is shattered, ‘apartheid’ reigns, there is ‘racism’ all over – or that Israel is abandoned, on the brink, betrayed by the world.

I’m noticing especially with my American friends that when Trump does something they don’t like they say he’s racist, when Benjamin Netanyahu does something that they don’t like they say Israel is racist. And that is a kind of apocalyptic thinking which you can afford to have when you’re having this idealised relationship with this country that you feel is disappointing you – but that you can’t afford to have when you actually live in a country.

No matter how far Left or Right you are in Israel, you’re actually living this not-yet-ism because you’re part of the society and you experience all the joys and all the frustrations in a more nuanced way. Not-yet-ism is about humility, about being grounded in the reality, about that Fitzgeraldean stance towards the world.

Visiting Israel helps people make a much deeper, multi-dimensional connection to the place and its people. It is the greatest asset that we have in terms of strengthening the Israel-diaspora relationship. When someone has been in Israel and met real people, they can’t give up on it as easily when Netanyahu or the Israeli Left does something they don’t like. And yet, although when you visit, you see the nuance, the normalcy, somehow, as soon as you go back to the UK or the US or wherever, you’re back seeing Israel through the media’s distorted lens.

Diaspora Zionism: From ambivalence to a partnership of equals?

CB-D: The diaspora section in your book is something that Hertzberg didn’t have but you decided to include. Why was that, and how do you think the relationship between Israel and the diaspora has evolved over the years?

GT: Hertzberg did include some diaspora voices, but not as a distinct component of Zionism. I thought that it was important to add the diaspora voice because Zionism started as a critique of life in the diaspora. Back then, Zionism was partially about the ‘Jewish problem,’ which it saw as anti-Semitism but also as assimilation. I thought it was important to acknowledge the power and centrality of diaspora Zionism and to appreciate its evolution.

The relationship begins with a certain amount of ambivalence. In the early 1900’s, recently arrived immigrant Jews in London, New York and Montreal felt they had arrived in a new promised land and didn’t want to start worrying about the old promised land. But because of the deep force of Jewish peoplehood, they did, starting with donations. And even those who went to the universalist extreme of the Reform Movement and had at first rejected the need for peoplehood and a state, changed that stance after the Holocaust. So there is a move from passive to more active forms of diaspora support because of the power of 1948 – when the establishment of Israel becomes the great Jewish building project of the 20th century.

For many in the diaspora, the period leading up to the Six-Day War in 1967 was a profound moment. People feared another Holocaust and they realised that if Israel were to be destroyed it would affect them. What followed the victory was an amazing empowerment – in the Soviet Union, the US, the UK – and we see a new paradigm of connectedness, of taking responsibility and of solidarity. Yet built into that new relationship is a kind of mutual condescension. Israel looks at the diaspora in Ben-Gurion terms as doomed due to assimilation and anti-Semitism. The diaspora Jews look at the drama and trauma of the 1948, 1956, 1967 wars and feel that they are lucky to be living in America and England and are happy just to write cheques. Both felt they are saving the other.

In the 1990s, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks wrote a powerful book in which he anticipated the emergence of a new mutuality, a move from philanthropic Zionism to identity Zionism. For Sacks, it’s no longer a question of physical survival but of spiritual survival. Israel will demonstrate the multi-dimensionality of Judaism, energising and inspiring Jews to build a modern community, because there is nowhere else we can feel 24/7, 3-D Judaism in such a profound way. So diaspora Jews have finally understood that Israel’s not just the insurance policy. It’s not just about anti anti-Semitism. In this age in which post-modernism is spreading, where intermarriage is not just an opportunity but actually seen as a plus (and Jews marrying Jews is considered by some such as Michael Chabon as just a ‘ghetto of two’), we have no choice but to use and appreciate Israel as an asset and create a more mutual balance.

At the same time, as diaspora Jews started appreciating Israel as what Rabbi Sacks calls their ‘classroom,’ Israelis started realising that we have no stronger moral asset than our friends in London and Washington who are fighting to ensure that Israel has allies aboard.

CB-D: Do you not think the relationship between diaspora and Israel is also changing because this generation of diaspora Jews doesn’t see itself as less than those who live in Israel? They want and expect a relationship of equals. Secondly, there is a competing argument here, which is that the regular Israeli doesn’t really care about the Jewish world and American Jews are increasingly disengaged and disappointed in Israel and feel it doesn’t really reflect their values. So while there is an understanding of mutual need is there not another trend of mutual ambivalence?

GT: You’re obviously right, whereas an older generation tended to look at Israelis as superheroes and better than us, now there is a new generation and new voices that look down on Israelis as not necessarily good Jews, because they’re not ‘Tikun Olam-ers’. I call it ‘Isaiah-ans’ (the book of prophets which in some places advances a type of utopian ‘wolf lying down with the lamb’) versus ‘David-ians’ (coping with a physical, violent reality).

I’m well aware of the two trends. It’s true that too many Israeli school kids don’t learn about diaspora, don’t learn about Zionism, don’t understand that as A.B. Yehoshua teaches, that the definition of Zionism is a Zionist who understands that Israel is not only a state for all its citizens but also is a state for the Jewish people and that’s why the Law of Return is legitimate, (I’m purposefully pulling someone from the Left). So I say, shame on us in Israel for not educating properly, for reducing Zionist education to a form of ‘who said what to whom,’ of teaching kids to know their five to 10 to 15 key dates and key facts, key quotations even, but to forget our core ideals.

Obviously I also have a critique of the American Jewish and the diaspora Jewish condescension towards Israel. I see both challenges and opportunities. Every ‘Birthright’ group meets young Israelis and you see the profound effect this has not only on the diaspora participants but also on the Israelis. They both discover a new dimension to their identity, a new kind of Jewishness, and a new sense of mission.

CB-D: What do you say to people who argue that by its nature Jewish nationalism, by re-establishing a state in the Middle East where there was already an ‘other’ who were a majority, cannot be liberal nationalism, but only an ugly, tribalist nationalism that puts one ethnicity above another?

GT: This is our homeland. Everyone’s home has its own challenges as well as its own blessings. I’m well aware we’re talking in the context of the pain of the Nation-State Law, but if we look at our track record with all Israeli citizens, there is a lot to be proud of. Often we’ve shown what Daniel Gordis calls the ‘promise of Israel,’ that we can teach the Arab world a different model than the American model of giving up on your nationalism, of giving up on having tribes.

The second thing is deeper and goes to the heart of not-yet-ism and this very-Jewish dance between the ideal and the real. You have to play with the cards you’re dealt. This is our lot and this is our opportunity. We’ve done so much good that those people who want to negate our right to exist, and who don’t see that we’re part of a very small minority of functional democracies in the world, fail to see such the great job we’ve done.

‘Liberalism’ isn’t some good conduct pin you get for being perfect and living without complexity. It’s an ideology in which imperfect human beings do their best to maximize equality, liberty, democracy in the region and reality they control.

Look at the tremendous progress Israeli Arabs have enjoyed. Look at the way Israel’s Declaration of Independence, and its 70-year-track record, puts Israel way ahead of most multi-ethnic pluralistic countries. And look at other liberal democracies – especially the US, Canada, Australia. They, too, had some individual natives displaced during the founding – but few question their legitimacy as countries or as liberal democracies. Remember, Jews are, as Irwin Cotler, the human rights activist says in the book, the original aboriginal people – an indigenous people tied to the same land, speaking the same language, reading the same holy book, living the same culture – with adjustments – for the last 3,500 years. To reduce Zionism to ‘we displaced “an other” who were a majority’ misses the complexity of our history. I call it ‘two people in love with the same land’. And it is not the Jewish people who are the ones trying to exterminate or negate ‘the other’.

There is a key line in the book, which I take from Ameinu, a progressive group in the US. They say that liberal Zionism is not an oxymoron. In fact, it’s probably the reason why in building the six schools of Zionist thought I did two things: I added an ‘s’ to make it ‘Zionisms’ in order to include those from Left and Right, secular and religious, to tell them all that they are part of the Zionist conversation, the Zionist heritage and the Zionist future. Adding the ‘s’ was also an attempt to move from exclamation points to question marks (the ‘s’ looks like a question mark).

Furthermore, try telling the story of Israel without talking about liberal and progressive ideas, without talking about the Kibbutz, Ben-Gurion, Meir, Aloni. Looking backwards, I cannot take out liberalism and progressivism from the history of Zionism and I cannot take them out of the future of Zionism either. I purposely describe it as a liberal nationalism and I call Ze’ev Jabotinsky a liberal nationalist. But I also need my post-modern extremist friends to be liberal nationalists. While I make a broad tent I also have my red lines.

CB-D: Who are your favourite three thinkers in the book?

GT: There are some essays I keep coming back to. One is ‘Revolution and Tradition,’ a brilliant essay by Berl Katzenelson. He discusses the need to remember and the need to forget. He argues that we are nothing if we don’t remember who we are, if we’re not connected to religion, to this land, to our heritage. But we’re also nothing if we are handcuffed by the past and don’t have that ability to forget things, so that we can be innovative and revolutionaries. It goes back to Theodore Herzl’s Altneuland, the old-new land. To combine universalism and particularism is deeply Zionist. To be rooted in time and place and also relevant to today is also deeply Zionist.

On the religious side, there is ‘kol dodi dofek’ by Joseph B. Soloveitchik. It means ‘Listen, my beloved knocks’. I felt I was bringing this back into the Zionist conversation. When ‘the Rav’ first wrote it in 1956, it was read by very few people outside the religious world. There are two amazing things about the essay. One is that Soloveitchik moves back and forth between a Dvar Torah steeped in Jewish traditional texts, and contemporary headlines – another example of the old-new. But he also refers to something very profound which David Hartman and others have picked up on, which gets to this core of not-yet-ism. Are we just a community of fate (what Hartman calls a community of Auschwitz – a community defined by anti-Semitism) or are we an Edah, do we have a vision? Are we a community that is about doing and changing? That’s a religious idea, but it’s also a very Zionist idea.

Third, there’s a nice parallelism between my essay ‘Why I am a Zionist’ and Yair Lapid’s essay of the same name. My essay was written when I was living in Montreal, trying to explain Zionism as a liberal national movement that gave us an opportunity to go back to our homeland. The beautiful thing about Lapid’s essay is that his Zionism is full of the texture of an Israeli life: How he gets choked up when he sees his kids in uniform; how proud he is when he’s seen the Statue of Liberty and leaning tower of Pisa but comes home and sees these amazing miracles that we have here. It’s about the joy of Hebrew, a language in which you can both bless and curse. It’s a profound monument to the prosaic and that’s ultimately what Zionism is about. When you read his essay you see the difference between those living in a vacuum in the diaspora and those who are living it every day, with the uniforms and the sweat, the accomplishments and the frustrations. That’s a profoundly Zionistic and progressive idea. The real test for our ideals and for our values isn’t when we are Isaiah-ans but David-ians. It’s not when we’re sitting there with no power and wagging our finger but when we actually have to use our hands to build something that we are put to the test.

CB-D: That’s connected to an argument George Steiner and others make, that Judaism was intended to be the conscience of the world and one couldn’t do that in a sovereign state which engages in war and realpolitik. But what you’re saying is that the challenge is to go back into the game of thrones but to behave in a reasonable way.

GT: And to get it right! It is delightful to take advantage of your suffering and try to make it an ideal but this is where the extreme post-modernists, the far Left of the Reform / liberal movement and the ultra-Orthodox agree, and they’ve all distorted Judaism, I believe. I don’t care if you have a hipster beard or a long black beard – you’re distorting what Judaism is. Judaism is what I call an Oreo cookie; without that mix of cream and cookie you just don’t have a cookie. In Judaism, you have to have both the religious part and the nationalism part. If you try and suck one part out, it doesn’t work.

The imposition of Israeli citizenship on Arabs is contrary to the UN decision to divide Palestine into two states: one for Jews and another for Arabs.

The Arabs in Palestine already have a state in which the Jews do not live. . ALL Jews were expelled from the Gaza Strip and from areas A and B.

It’s time to ALL 6 million Arabs of Palestine to obtain the citizenship of the Palestinian National Autonomy.

Israel must stop to impose Israeli citizenship to the hostile nation.

Citizenship of a Jewish State – for Jews Citizenship of an Arab State – for Arabs .

Only then will begin economical, political and physical separation between Jews and Arabs.

Without this, peace in Palestine is impossible.

Every nation must live in its own country. This is the essence of the UN decision on the partition of Palestine.