Blake Flayton is a columnist for the Jewish Journal and Samuel J. Hyde is a writer and political researcher at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. They argue that the city now has a non-Zionist majority and is burdened by increasing poverty, experiencing a significant exodus of its residents, and plagued by ever-increasing tensions between its ‘tribes’. They warn that ‘Jerusalem today should serve as a profound cautionary tale for the future of Israel as a whole, shedding light on the consequences that arise from annexing too much territory to the east in the name of an ideological falsehood.’

Jerusalem is the irrefutable capital of Israel. Not only does the state’s government operate out of it, but it’s also true that Jerusalem has been the capital of the Jewish people for over three thousand years. Our liturgy, history, and identities are built into the hallowed walls of the Old City. Jerusalem, or Zion, would come to animate the movement to rebuild the Jewish homeland, and the prospect of Zionism without Zion makes even the most secular supporters of Israel uncomfortable.

And yet, amidst all of this, present-day Jerusalem faces a dilemma, for the policies pursued in its name have become increasingly unsustainable. Its leaders and those who wax poetically on its symbolism continue to widen the gap between reality and expectations, all under the recitation of a comforting myth called ‘united Jerusalem’. For them, Jerusalem exists as a harmonious triumph, where diverse religious and ethnic groups peacefully coexist. However, this portrayal is nothing more than a facade.

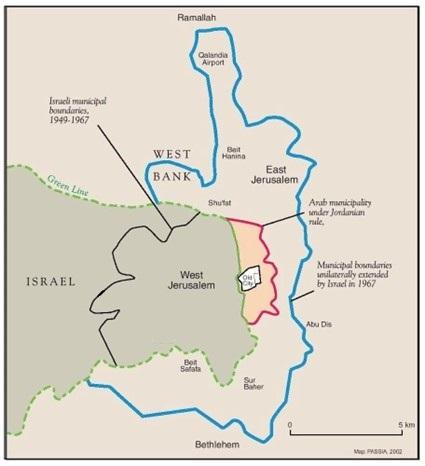

The contradiction between the idealised notion of a united Jerusalem and the harsh realities faced by the city today can be traced back to Israel’s decisive victory in the 1967 Six-Day War. Israel did not seek conflict in 1967, but through defensive warfare, it gained control not only over what many Israelis now consider ‘East Jerusalem,’ including Palestinian neighbourhoods like Silwan and Sheikh Jarrah but also over a large expanse of land surrounding the city that was previously part of the West Bank under Jordanian administration. This land, now part of Jerusalem’s municipal borders, includes over thirty Palestinian villages. In other words, ‘united Jerusalem’ encompasses not only six square miles of tightly packed apartments near the Old City and the holy sites but also over seventy square miles of predominantly Arab-populated land, including refugee camps. In the aftermath of the war, the Israeli government declared Jerusalem its ‘united capital’ and annexed this entire area. The war had a profound impact on the Israeli psyche, fostering a sense of euphoric triumphalism and invincibility. However, this mindset has also led Israeli leadership to overlook pragmatic considerations and make unwise decisions in regard to Jerusalem. Issues related to demography, education, and the economy are particularly critical.

First, if Jerusalem were to be truly united, the Arab population formerly under Jordanian rule who considers themselves Palestinians would certainly have to be awarded equal rights of Israeli citizenship, not just residency. According to the Jerusalem Institute, at the end of 2017, East Jerusalem had a population of 595,000 inhabitants, of which 361,700 (61 per cent) were Palestinian, and 234,000 (39 per cent) were Jewish-Israelis, whereas 99% of West Jerusalem’s residents were Jewish. It’s subsequently important to recognise that the Jewish population in both West and East Jerusalem is not a bulwark of Israeli-state interests. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, a near 35% of Jews in Jerusalem’s municipal borders identify as Haredi, and traditionally do not ascribe to the Zionist, nationalist agenda of a sovereign Jewish and democratic state. Meaning, if Jerusalem were truly ‘united,’ only a fourth of the population would be Zionist Jews in the classical sense.

Apparently these numbers do not pose a problem to those who believe the city is the united capital of Israel. To them, the capital of the state can indeed withstand an overwhelming majority of those calling it home not believing in the state’s founding principles.

The educational landscape in Jerusalem’s municipal borders is reflective of these numbers. As of 2022 30 per cent of Jerusalem’s children are enrolled in Israeli state-run secondary schools, which are dedicated to promoting the ideals of Zionism and the modern Jewish and democratic State of Israel. The number drops to 24 per cent for elementary schools. In contrast 37 per cent of children attend Ultra-Orthodox Haredi secondary schools that prioritise theology, sometimes accompanied by anti-state rhetoric in textbooks. Another 33 per cent of students are being educated in Arab schools that explicitly reject Zionism. In some East Jerusalem schools, the curriculum follows that of the Palestinian Authority, known for incitement and antisemitism.

Because Palestinian residents of Jerusalem mostly refuse to have their children taught from a curriculum determined by a body they see as illegally occupying their city they often receive a lower quality of education compared to Jewish residents attending Israeli state-run schools. This educational disadvantage hinders their ability to access employment opportunities that require a higher level of education, thereby exacerbating the adverse effects of labour market participation among the majority of Jerusalem’s Palestinian residents.

Concurrently, many of Jerusalem’s Jewish students are enrolled in the ultra-Orthodox education system, which often lacks core academic subjects and limits students’ ability to pursue higher education and enter the job market in lucrative professions. As a substantial portion of the Haredi community relies on government subsidies and social benefits, the burden on taxpayers, who are mostly secular or non-religious, increases, straining public finances and worsening inequality between those who bear the economic burden and those who opt out. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel (CBS), the unemployment rate among the ultra-Orthodox population in Jerusalem stood at 48 per cent in 2022. Additionally, the unemployment rate amongst Arabs was 31 per cent for men and 74 per cent for women in the same year, resulting in 39 per cent of families and 51 per cent of children living below the poverty line within Jerusalem’s borders, which is nearly double the national average in Israel. These figures highlight a significant disparity between the two groups compared to the overall unemployment rate in Jerusalem, which was 5.7 per cent in 2022.

If Jerusalem were truly ‘united,’ Israel would indeed have to act to improve these damning statistics. It would need to do its part in holding the Haredi population responsible for equal contribution to the economic burden to avoid the city’s financial collapse, and also incorporate the entire eastern part of Jerusalem by investing across the board in Palestinian infrastructure, housing, and education.

These poor educational trends indeed have consequences. The Jerusalem Institute’s 2021 study entitled The Demography of Jerusalem: Trends and Challenges showed that the city’s secular population has fallen by 10 per cent since 2010. The decline is attributed to a number of factors that are reflected in the educational and demographic realm, including increasing religious and political hostilities between Jews and Arabs. As of 28 May 2023, there have been a total of 24 terror attacks in Jerusalem since the beginning of the year, resulting in 24 deaths and 154 injuries. The majority of these attacks have been stabbings, with a few involving shootings and car rammings. The targets of these Palestinian attacks have included both Israeli civilians and security personnel.

Yet, for decades, the government has done virtually everything in its power to expand construction for Jewish property in East Jerusalem, while removing Palestinian homes through a process of legal loopholes, litigation and development plans. A Rabin government-led inquiry found that

an Israeli governmental mechanism was established in the late 1980s dedicated to transferring properties in East Jerusalem from Palestinians into the hands of settlers …this mechanism was founded under the leadership of then Minister of Housing, Ariel Sharon. Dozens of properties were transferred to Elad and Ateret Cohanim organisations without auctions and in violation of the rules of proper administration. Millions of shekels have since been handed over to these organisations…

In a contemporary example of how this trend has continued, in 2022 the government allocated the Elad Association 28 million shekels in public funding from the Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage Ministry, the Jerusalem Municipality and the Jerusalem Development Authority to develop the Hinnom Valley project, for the construction of a “tourism zone,” on disputed land over which Palestinians claim ownership. Such efforts run parallel to East Jerusalem’s Palestinian residents’ lack of a variety of basic social services including healthcare, post, and water and sewage systems. If Israel wants to avoid claims that it is imposing a system of hierarchy onto its residents, then it cannot have it both ways – it must act to reduce inequality. Such no doubt costly expenditures would all but worsen the bitterness of Jerusalem’s middle class, which is already trickling out of the city and grappling with a spiking cost of living.

In 1990, former Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek expressed that the city was not truly united, in saying

the Jews and Arabs will not easily love each other in this generation or the next, and it isn’t necessary. I don’t know where different peoples love each other. The question is whether, with all the antagonism which exists, you can find a way to live together. Can we who run the city be tolerant enough to give others a chance to live their own way of life?

Similarly, in 2012, fellow former Mayor, and former Israel Prime Minister, Ehud Olmert acknowledged that his government had not taken sufficient action to truly unite Jerusalem. Although there was a government decision in 2018 which allocated 2.1 billion shekels for economic development and reducing social disparities in East Jerusalem, there has been no subsequent progress or follow-up to this important initiative.

Still, the deception of a ‘united Jerusalem’ continues.

In late May, thousands of Israelis descended on Jerusalem to commemorate the ‘unification’ of the capital, known as Yom Yerushalayim. Yet the behaviour of several ultra-nationalist groups in attendance revealed the abject hollowness of this perspective. ‘May Your Village Burn,’ shouted teenagers, while others chanted, ‘Jews are my beloved, Arabs are sons of bitches.’ One woman, speaking with an American accent, donned an Israeli flag and yelled, ‘Leave, go home, this is Jewish country. For Jews only!’

What objective observer could possibly view this reality as some harmonious ‘drum-circle’?

Due to Jerusalem’s ongoing insistence that it is indeed united, it is now a city with a non-Zionist majority, burdened by increasing poverty, experiencing a significant exodus of its residents, and plagued by ever-increasing tensions among its population groups. And yes, it is a city with no foreseeable prospects for change. But what happens in Jerusalem doesn’t stay in Jerusalem. The city serves as a reliable microcosm for the entirety of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Many proponents of a ‘united Jerusalem’’ similarly advocate for ‘uniting the country’ through the annexation of the West Bank. The issues facing Jerusalem today should serve as a profound cautionary tale for the future of Israel as a whole, shedding light on the consequences that arise from annexing too much territory to the east in the name of an ideological falsehood. If Israel were to extend sovereignty over the West Bank, over the roughly 2.5 million Palestinians who live there, approximately 36 per cent of whom live in poverty, Israel would need to not only grant civil and political rights to all under its sovereignty, but also to invest heavily in housing and social services for the Palestinian population. Jerusalem serves as a powerful reminder of the pitfalls that the Zionist project will face when driven by these misguided motivations for the future of the West Bank, particularly a demographic death knell. The Palestinian population of the West Bank is significantly larger and younger than the Israeli population in the territories. If Israel were to annex the West Bank, non-Jews between the river and the sea would become the majority. In order to maintain a Jewish state in such a scenario, it would require the organisation of the state’s public affairs in a blatantly nondemocratic manner, akin to the situation in Jerusalem where Palestinians are granted residency but often not citizenship rights, regardless of whether they undertake Israel’s bureaucratic process to achieve them. Governing an Israel of this nature cannot be both Jewish and democratic.

The general absence of jobs, coupled with the high cost of property and poverty of much of the population – not unconnected to the consequences of annexation – has led Jerusalemites to move to other cities within Israel. If this were to become the fate of the entire country, with the West Bank annexed, the question arises: where would they go?

In his novel The Suicide of the Jews, Israeli futurist Tsvi Bisk addresses the fate of Israel without specifying any concrete annexation policy, only predicting the future should Israel continue down its path of expansionism, coupled with skyrocketing rates of Arab voter participation. Concluding his chapter on ‘The Political Turning Point’ with a reflection on the unravelling of the Zionist project, Bisk writes:

By 2032, the Arab MKs (now 25 in number) had established extensive log-rolling agreements which constituted a de facto coalition with the Haredim. They automatically voted for every bit of religious and welfare legislation that the Haredim proposed so long as the Haredim supported every bit of development and education proposals of the Arabs. As a result, Israel became more and more theocratic and more and more suffocating to non-Orthodox Jews, and the exodus of young talented Jews from Israel increased apace…

He continues: ‘By 2038, the majority of Members of Knesset were Arab or Haredi and by 2046 the majority was Arab. A bill was introduced to change the name of the country to Palestine. By 2048, the country of Israel ceased to exist, 100 years after its establishment.’

Dystopian as Bisk’s novel may be, with Jerusalem as a testament, unthinkable its warnings are not.