Barry Finger is a frequent contributor to US socialist journals, a former shop steward and activist with the Public Employees Federation. In this review essay he urges the left to face up to the reality of left antisemitism and to consider the radical democratic alternative offered in the writings of Jean Améry and Daniel Randall.

Strike the Zionist dead, turn the Middle East red. (German New Left slogan of the 1970s)

Y’all love to add the word liberal in front of the most evil things and its unhingedddd. Wtf is a liberal Zionist? What’s next? Liberal Nazi? Liberal colonizer? Liberal murderer? Liberal imperialist? Liberal fascist? (From the world of Twitter)

Whoever attacks ‘Zionists’ but under no circumstances means to say anything against the ‘Jews’ is deceiving himself or others. The state of Israel is a Jewish state. Whoever wishes to destroy it, overtly or by means of policies that can effect nothing but such a destruction, is pursuing the hatred of Jews of former times and as it always was. (Hans Mayer)

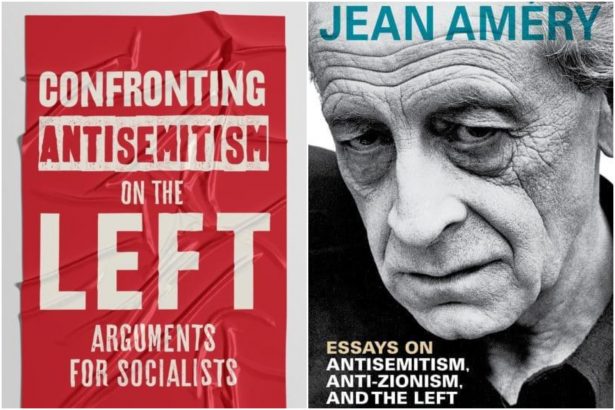

I review books by two noteworthy socialist thinkers here, both of whom grapple in their own ways with Mayer’s conclusion.[1] The work of one – a product of mature reflection, written by a noted resistance fighter, concentration camp survivor and renowned Jewish philosopher raging incandescently against a left that turned on the Jews; the other, by a young trade union militant who dissects antisemitism on the left with a steely detachment and the calm eviscerating deliberation of a legal scholar. Jean Améry, a comrade and accolade of Sartre, was a proud and proudly defiant leftwing atheist Zionist. Daniel Randall, influenced by the Marxist academic Moshe Postone, by his movement comrade Robert Fine and by the late libertarian socialist Steve Cohen (author of the freshly reissued That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Antisemitic), is a self-identified heterodox Trotskyist internationalist and ‘anti-Zionist-Zionist.’ If Israel in the abstract was central to Améry’s Jewish identity; Randall is, in Isaac Deutscher’s term, a non-Jewish Jew, rooted in Jewish awareness, yet politically suspicious of the excesses and crimes to which nationalism—including the nationalism of the oppressed (alternatingly Jewish and Arab/Palestinian)—often gives license.

Although written decades apart—Améry’s collection, an occasionally repetitious, yet always penetrating presentation without a central organising structure, and Randall’s tightly systematised historical focus, ultimately align in this: modern leftwing anti-Semitism, resurrecting primitive tropes from previous waves of Jew-hatred, is now inescapably intertwined with the Israel/Palestine conflict. Although Améry assumes a more partisan stance, neither author is blind to the injustices historically borne by both sides. Améry, however, is the more pessimistic of the two, at once horrified and resigned to a state of permanent exile beyond the orbit of the organised left, a left unable to free itself from habitual myths and incendiary vocabulary, mechanical yay-saying and unconditional support for Palestinian irredentism that constitutes the only acceptable expression of Palestinian solidarity.

Nevertheless, both authors are united in their belief that a two-state solution is the only viable, even unavoidable, next step in Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation.

Randall believes that significant elements of the mass left–trade unions, social democratic and socialist parties, anti-war organisations and human rights movements–are still salvageable for that purpose through theoretical education, reinforced and amplified by the concrete opportunities afforded through joint Israeli/Palestinian struggle and wider movement building in support of such struggles. It is largely by embracing this perspective that socialists can address the collective grievances and well justified fears of two victimised and vulnerable peoples without succumbing to the one-sided poisons of nationalism. His aim is a politics that levels up rights and freedoms, without upending and reversing the axis of oppression. This sets the framework for his orientation towards antisemitism in the British Labour Party: an emphasis on discussion and an enlightened return to internationalist first principles through comradely persuasion rather than welding, as an initial response, the heavy hammer of expulsion for intemperate outbursts of Jew-hatred.

Neither author can/could survey the socialism of their day and find it anything other than wanting. Socialism has, as in so many instances, when called upon, not only failed, but also betrayed the elementary demands of internationalism. It would belabour the issue to rehearse the sorry litany. Randall argues that the enduring (not his words) appeal of antisemitism for elements of the left resides in its seemingly anti-hegemonic orientation. By claiming to punch up against well positioned Jews or ‘Zionists’ it insinuates itself as a legitimate current of an organising worldview of the powerless against global forms of domination—capitalism and capitalist imperialism—a current, however errant, that nevertheless can feed into socialism. This, for example, was behind the early opportunistic German social democratic ambivalence towards antisemitism: placating antisemitism when it leaned against capitalism, while warning against the dangers of ‘philosemitism’ lest it prematurely disrupt the evolving allegiances of primitive militants who were assumed to be on the march towards socialism.

All of this brings us full circle. Too much has been made of the ‘Jewish Question’ as a minority problem. It is more properly a problem of majority attitudes. And this includes the prevailing attitudes of socialist movements confronted with such convictions from below. Socialists are challenged by the task of engaging the masses where they ‘are’ politically, of encouraging the spirit of combativeness, while challenging them to jettison atavistic beliefs. Yet, it has often been the case that minorities who are oppressed and who are vulnerable to oppression are not necessarily the most disadvantaged. And this is a problem the left finds difficult to recognise, much less handle. This vulnerability was true not only of the Jews of Eastern, Central Europe, and parts of the Ottoman Empire where Greek and Armenian communities likewise periodically prospered, but also of the Chinese of Indonesia and the Tamils of Sri Lanka to name but two. It is no less true of American, British and French Jewry today. A glaring democratic deficit adheres to socialist movements that fail to assert the right to minority identity, to cultural expression and to religious exercise based on the economic privileges that such minority communities allegedly enjoy.

At their worst, Marxian socialists in the past were negligent in shaking off antisemitism for fear of damming a stream that feeds into the larger flow of social insurgency. The problem is that the radical Left is now actively complicit in propagating it. The ‘Jewish Question’ of yesterday is the ‘Israel Question’ of today. And there is no way of reading Randall or Améry otherwise. In either case, what we are dealing with here is not the antisemitism residing in the personal prejudices of the individual mind, though it may well coexist with them. It is rather a broad, political/cultural formation having a dominant ideological presence, a complex internal logic and a respected, promiscuously self-referential arsenal of totemic literature. These give leftwing antisemitism the power to transmit itself to new, future believers through the standard process of gradual familiarity leading to eventual conversion. And, insofar as the belief that Zionism—as a driver and principal beneficiary of ‘racialised capitalism’—is an integral part of the political complex of recruitment to contemporary socialism, it presents formidable obstacles to those on the Left who seek to resist its blandishments.

Améry and Randall trace this back to the baneful shadow that Stalinist imperialism cast over the broader left as it inserted itself into the Arab-Israeli conflict. Stalinism was no stranger to antisemitism. It eagerly exploited Russian and Eastern European traditions of antisemitism and consolidated its own virulently nationalist rule by purging its ranks of untrustworthy ‘cosmopolitan’ elements, i.e. Jews (often loyally pro-Stalinist Jews). The Russian ruling class kept the spigot of antisemitism always well lubricated. It could be shut down when the ruling bureaucracy used the Jewish plight to recruit Western allies in the war against Hitler or when it saw strategic, regional advantage in Israel driving out British imperialism. But the spigot was opened wide again when the post-war Arab reawakening was ascendant. In this regard, Stalinism was uniquely equipped to meet the Arab nationalist drive to diminish Western influence by exploiting their ideological commonality. Antisemitism cemented Stalinism’s bona fides with the rising secular nationalist forces in the Middle East, unshakeable in the conviction that the road to Arab unity ran through Jerusalem.

Most forms of past Jew hatred, short of Nazism, made a distinction between good and bad Jews, or bad Jews and salvageable Jews, or Jews who either reject their Jewishness and join the camp of the good or who advantage that camp by revealing the secret iniquities and perfidy of ‘the Jewish people.’ Stalinist antisemitism introduced a separation between the blameless, obsequious Jews and the evil, tentacle grasping Zionists. And, with an unctuous bat of the eye, coyly insisted to the world that by this distinction alone they had vaccinated themselves against the charge of antisemitism. It was all about the hatred of a power-grabbing ideology, not of a people. And, in any case, their anti-Zionism still offered an escape valve to ‘socialist’ redemption for those Jews who wished to defect to the ‘Arab Revolution Against Imperialism’ and advantage the power politics of Stalinist expansion.

There have also arisen independent strains of anti-Zionist Jewish Leftism, self-proclaimed defectors to the cause of the good, by those who invoke the noble traditions of the Jewish Labour Bund to justify their support for BDS and Israel-eliminationism. Nevertheless, these appeals are superficial and ironically tone deaf. The Bundist program arose out of the specific environment that prevailed in the Pale of Settlement. None of today’s putative Bundists raise the obviously absurd demand for Jewish communities to reconstitute themselves as culturally autonomous Yiddish speaking national minority enclaves within the nations they inhabit.

Yet, what is utterly lost to these would-be adherents of Bundism, is the historic paradox that post-Holocaust diasporic Jewry identifies as ‘Zionist’, yet often functions as ‘Bundists.’ In practice, they reject the ‘ingathering of the exiles’ but remain sensitive to threats menacing any Jewish community—including the majority Jewish state—to exist unmolested wherever it is rooted. And while they do not share the optimism of early Zionism that ‘normalisation’ of Jewish existence through the creation of a national home would attenuate antisemitism, they nevertheless defend the right of the Jewish community of Israel to assert its communal identity nationally in the freely chosen form of a state. The ties that bind diasporic Jews to Israel are, in other words, the same that tie it, and have historically tied it, to one another through time. That these loyalties are now disparaged as ‘Zionist’ is both unduly flattering to Zionism and ahistoric.

But the disparagement of those loyalties is also revealing. It reveals a suspicion of intra communal Jewish loyalties and of secret political motives, the building blocks of Randall’s primitive antisemitism, camouflaging itself as anti-Zionism. For all formulations of the ‘Jewish Question’—now posed as the ‘Israel Question’—still revert back to the harm Jewish loyalties purportedly inflict on humanity and the need to locate and eliminate those harms by addressing the concentrated sources of Jewish power.

Between retreat to the ghetto and total assimilation into the nationalism of the host countries, a broad and fluid range of cross-fertilising ideologies arose within pre-Holocaust Jewish communities. Synthesising competing and overlapping movements, they grappled with the problems of communal self-preservation in the spirit of modernity. The various factions—Yiddishists, Hebraiscists, autonomists, Zionists, socialists (Bundists), cultural and religious reformists—all advanced strategies to navigate the dissonance between universalism and particularism.

So too emerged the broader trends of socialism with which Améry and Randall identify. These variants of socialism posit capitalist exploitation as the constituent agent through which other, secondary forms of domination and oppression (national, racial, gender, ethnic, etc.) are sustained. Broadly speaking, because workers are exploited collectively, but oppressed in specific and diverse ways—which they experience in common with non-exploited subaltern and vulnerable populations—any successful struggle for working class liberation necessarily awakens the need to address and encompass the widest spectrum of social grievances. This socialism perceived itself as a broad social movement for freedom and equality driven to challenge capitalism by its working class core. Without that core, such struggles would expand the democratic plurality of civil society, but leave the sustaining structures of exploitation unmolested. It was this understanding, no doubt, that once attracted masses of Jews, and not just working class Jews, to socialism.

The ‘old’ socialism understood formal legal and political equality attained under some evolved forms of capitalism to be true democratic advances, extracted at great working class cost, whose fullest expression awaits the abolition of classes. The contemporary left, in stark contrast, is post-modern. And that is also why Améry and Randall’s work will, sadly, appeal to a different and diminished order of humanity, those who still adhere to the Enlightenment values from which the Left emerged.

Post-modern socialism, the socialism that grew out of the New Left’s Third Worldism, Maoism and Orientalism-in-reverse, no longer locates power discrepancies primarily in class inequalities and the ramifying limitations those deficiencies impose on democracy. It is categorically suspicious of democracy and universal rights, seeing them as ideological fog that obscures the true sources of inequality—the global defence of racial privilege. It replaces exploitation as the central dynamic of capitalism with imperialist wealth redistribution from global south to north, from people of colour to broadly defined white elites, and sees this dynamic recapitulated in the internal structures—the race relations—of the capitalist metropoles. At its extreme, it writes off the socialist potential of white workers for being junior partners of capitalism in the global structures of imperialism; at a minimum it refuses, for parallel reasons, to ‘privilege’ class over race. It repurposes the language of the old socialism with discussions of ‘racialised capitalism’ and ‘racial exploitation’ and reconsiders reactionary third world movements and even authoritarian, intolerant religious ideologies that threaten to disrupt the imperialist nexus as now ‘objectively’ progressive.

That ‘new’ socialism predictably understands the national conflict between Israel and Palestine over contested territory as a racial conflict, not as a contest of competing chauvinisms. All the old internationalist values that Randall and Améry champion are irrelevant to it. For the ‘new’ socialism Israeli Jews are not a nation, but rather an entrenched white settler colonialist community. Israeli democracy, including hard fought LGBTQ+ gains, is not a conquest of human rights, but exculpatory eyewash for apartheid. Diasporic Jews who challenge this perspective are written off as apologists for white privilege and are cast out, on that basis, from progressive movements, demonstrations and struggles. Special, nominally Jewish, leftist organs prominently function to certify the anti-imperialist, anti-racist credentials of Jews who still wish entrée.

A settler community, in the single Palestinian state of the future, will be denied equal democratic rights with other Palestinians. The Israel-eliminationist left is quite clear on this issue. That is, Israeli Jews in any unified single state will be denied the basic democratic right of being considered a nation. They may, it is claimed, enjoy religious freedom and some rights to cultural expression, but they will not have the right to self-determination. There is not even a trace of binationalism, which at least gestures to traditional democratic principles, in all this. What is being proposed for Israeli Jews is akin to the dubious equality enjoyed by Ukrainians within Czarist Russia – all common rights, save the right of being a Ukrainian.

Améry and Randall offer radical democratic alternatives. Is there an audience for this?

References

[1] Daniel Randall, Confronting Antisemitism on the Left: Arguments for Socialists, No Pasaran Media, 2021, and Jean Améry, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism and the Left, Indiana University Press, 2021.

This review offers a lot of food for thought, and I found the reviewers points about the ‘new left’ retreat from class spot on, although of course hes not the first to notice it.

While the western ‘new left’ has replaced class with identity, and tried to make class another identity marker, Palestinians concerns are around the “class inequalities and the ramifying limitations those deficiencies impose on democracy” and they certainly dont view it as a ‘race’ conflict, even if thats the view some postmodern leftists are using these days.

And what I found curious, and it would be good if the reviewer can elaborate (and Im asking that comradley in case the tones lost on the internet) is that for all the great criticism of ‘new left’ idpol, the reviewer then pivots to “Israeli democracy, including hard fought LGBTQ+ gains, is not a conquest of human rights, but exculpatory eyewash for apartheid” which sounded like he was strategically using a bit of it (idpol) himself, or at least informing us that the Israeli state has, unless sexuality falls under something different ? And again, Palestinians are justified to be critical of that, and doing so doesnt necessarily bespeak of them being indoctrinated by new fangled postmodern leftism.

“A settler community, in the single Palestinian state of the future, will be denied equal democratic rights with other Palestinians. The Israel-eliminationist left is quite clear on this issue. That is, Israeli Jews in any unified single state will be denied the basic democratic right of being considered a nation”

Says who – are the ‘Israel-eliminationist’ left in Israel-Palestine, or is this the western ‘new left’ again ?

Can the reviewer point to quotes stating this ?