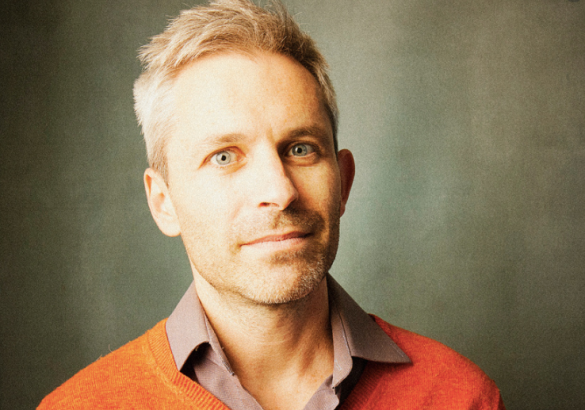

Peter Beinart’s essay ‘Yavne: A Jewish Case for Equality in Israel-Palestine’ saw him give up in the two-state solution and embrace the so-called ‘one state solution’. The essay sparked an international debate. Shany Mor argues that ‘Beinart doesn’t understand actual Israelis because he doesn’t care about the actual Israel. “Israel” for him is a projection, a cave shadow with which to imagine an argument with people and organisations in American Jewish life.’ This essay was first published on Medium.

In the years I spent as a grad student first in New York and later in England, I was often buttonholed by opinionated young Jews who wanted to give me an earful of ‘criticism of Israel.’ Some of it was ignorant blather, some of it was quite serious. Some of it I disagreed with politely (whenever that was possible) and some of it I agreed with, even wholeheartedly as my own views evolved. I heard it all, and I’d like to believe (though I’m no doubt being very generous with myself), that I was able to listen and engage with most of it, but I did notice after a few such encounters that there was one claim which led me, entirely by reflex and not by will, to shut down. Maybe it says more about my own weaknesses, I don’t know. But conspiracy-mongering didn’t make me stop listening, nor did Holocaust inversion or comparisons with apartheid. Such nonsense was upsetting, to be sure, and it did occasionally result in a raised voice or a bruised friendship, but it never caused me to just stop listening.

What would cause me to stop listening was the word ‘brave.’ Anyone, and especially any young American or British Jew at a fancy university, who saw himself (and even though ignorant anti-Israel obsessiveness was distributed across genders, the ‘bravery’ complex was almost always a symptom of male carriers) as brave for daring to criticise Israel was just not capable of thoughtful discussion. The claim of bravery, the self-image of a dissident voice speaking out against rigorously enforced dogma, was so patently ridiculous that it was impossible to take seriously anything that a person so afflicted might have to say about a topic that I knew well. And so it was that I encountered Peter Beinart’s recent fatwa on the Jewish state from Twitter posts hailing him as brave. Pro-democracy writers in Hong Kong, to say nothing of in mainland China, merit the description ‘brave.’ So too do LGBT activists in Egypt or Iran. To call a comfortable Upper West Side American Jew ‘brave’ for writing something against Israel says very little about bravery and very little about Israel, but it says a great deal about what the person making the compliment thinks about Jewish power in American public life.

This was the barely repressed subtext of the two big NYRB essays with which Beinart reinvented himself as a ‘critic of Israel’ a decade ago — and which I critiqued seven years ago. In all the years since, each time I was approached for a comment about some new bit of ‘bravery’ from Peter Beinart, I always declined. My explanation whenever I was asked why was that I didn’t disagree with the views Beinart claimed he held — for a Jewish state, against the occupation — I just didn’t believe those were his actual views.

It turns out I was right to doubt him.

In my 2013 piece I identified four themes to Beinart’s writing on Israel: (1) He makes sweeping judgements on scant evidence, that rely on out-of-date and out-of-context quotes. (2) Any observable outcome or effect or result of the Arab-Israeli conflict is for him an Israeli policy or the action of an Israeli subject on a Palestinian object. (3) He has no expectation of any kind of self-criticism by Palestinians or pro-Palestinian partisans and no capacity for a critical engagement with their actions and the effects those have on the conflict. (4) He consistently presents ideas that have been around for a long time as something new which he has just discovered, and thus manages to make them into a progressive reaction to Israeli actions rather than part of a long-standing rejection of sovereign Jewish life in the Middle East.

In 2013, this was most clear with his historically blind discussion of boycotts, which were central to the Arab strategy to prevent a Jewish state from coming into being and then, when that failed, an attempt to strangle it economically. In 2020, this is how he processes the old-new idea of one non-Jewish state in land of the former Mandate as an expected reaction to Israeli intransigence rather than the longstanding political programme of those who never accepted a Jewish state and never will.

This old-new idea Beinart is now openly advancing, though, it being Beinart, he has branded it under the most sanctimonious name possible, ‘equality.’ People opposed to legal abortion call themselves ‘pro-life,’ but no one with a modicum of intellectual integrity thinks that asking why your opponents in a policy discussion ‘are against life’ is a winning argument. If you oppose the end of Jewish sovereignty (but weirdly, no one else’s), then apparently you are against equality. This is the level of argumentation Beinart routinely resorts to now on Twitter when confronted with Israeli voices who actually aren’t so eager to see their hard-fought state be dismantled. Beinart, however, isn’t concerned with engaging with Israelis in any constructive way, and he wouldn’t know how to if he were.

For two years, Beinart had a regular column in Israel’s high-brow broadsheet Haaretz. It should have been an ideal venue for him. It is a left-wing paper read by cosmopolitan Israelis where his opinions (Bibi bad, Trump bad, etc.) met a sympathetic audience and, in a country without any widely read opinion journals, the best place to have an impact on public intellectual life. The column ran in Hebrew translation for about two years, and I honestly cannot recall even once that anything he wrote had even a minor impact or became a topic of public conversation or even manufactured controversy.

The column stopped running sometime in 2018 without anyone much noticing. It’s worth reminding his American acolytes who take his every pronouncement on this country as holy writs (and who find themselves having to conform to his increasingly pietistic demands regarding who must share a stage with him) just how little he understands Israel and how little purchase his ideas have even among left-wing activists and thinkers.

Beinart doesn’t understand actual Israelis because he doesn’t care about the actual Israel. ‘Israel’ for him is a projection, a cave shadow with which to imagine an argument with people and organisations in American Jewish life that Beinart resents deeply. Even as Beinart’s views on Israel have changed and changed again, his wrath at American Jews has stayed constant and his message consistent: American Jews must choose between their liberalism and their Zionism, between membership in good standing in the community of the good or, sounding almost like someone who tags a synagogue with graffiti, ‘our community’s complicity in the oppression of Palestinians.’

One could make a career out of correcting the errors in Beinart’s writing about Israel (and maybe somebody else should), but I’ll narrow my focus to just three things he gets wrong: the past, the present, the future.

PAST: A STATELY HOME

If someone had asked me this morning what I was in the mood to eat, I might have answered oatmeal or an omelet or maybe just some yogurt and granola. I also would have asked for a cup of coffee. But faced with the same question 12 hours later, it’s likely that my answer might mention steak or tacos or even a hearty salad and no coffee. You might rack your brains trying to analyse the reasons for this sudden shift. Did my tastes change in some dramatic way over 12 hours? Was I a committed vegetarian who left the fold, and, if so, why did I do it? Maybe a marketing campaign or a particularly persuasive friend had convinced me to change my entire approach to cooking and eating?

Or maybe you would just note that you asked the first question at 7:00 in the morning and the second at 7:00 in the evening, and that I hadn’t changed at all, but breakfast hunger and dinner hunger are not the same thing.

The second method clearly didn’t appeal to Beinart in considering why Zionists were by the 1940s so insistent on statehood rather than some of the more abstract ideas about a Jewish ‘home,’ as had occasionally been mooted in the half century before. Just as he does with the Arab-Israeli conflict, so here he is unable to see any observable fact without assuming that it can be explained entirely by Jewish or Israeli action — that should be judged as uncharitably as possible.

But it wasn’t Zionism that changed. The world changed in at least three very significant ways that required that the cause of Jewish self-determination take into account. First, the norm of state sovereignty went from a vaguely north Atlantic ideal to a global norm. Second, there was a Holocaust. And third, there was a conflict with the Arab (and to a certain extent, Muslim) world that impinged on personal and communal security of Jews in the Middle East and throughout the world.

In a world where most of central and eastern Europe together with nearly all of Western Asia consisted of multinational empires — and other parts of Asia and most of Africa consisted of distant imperial possessions — imagining a Jewish home in the Land of Israel as a protectorate or dominion made sense. Very little of the world’s land surface in the late nineteenth century was actually covered in sovereign states. The post-1945 world is absolutely nothing like this. Today, almost every piece of land except Antarctica belongs to a sovereign state. The entire surface of the world is covered in water, ice, and sovereign states. To be sure, the principle often comes up short in application. Borders are disputed; old colonial powers still exercise enormous influence in newly free and ostensibly independent possessions; functional responsibilities are occasionally distributed across boundaries or even among supranational organisations.

And so it was that Herzl and others spoke in a flexible language of self-determination for the Jewish people, occasionally referring to a ‘state’ and occasionally using terms like ‘charter’ or ‘protectorate’ or ‘commonwealth’ or ‘dominion’ or even just ‘national home,’ and eventually settling for a new legal concept after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, ‘mandate.’ You’ll notice that in today’s world there aren’t very many protectorates or mandates or dominions around.

There is, ironically, still a Jewish autonomous province centered around the Russian far eastern town of Birobidzhan. And, unarguably, some Jews do prefer to live in an autonomous Jewish district rather than a Jewish state (roughly 1600 versus 6.8 million), but I should think this argument has been adequately settled. (I was there in 2016, and I urge everyone to visit. The street signs are in Yiddish and Russian!) I’m not sure why Beinart wouldn’t mention Birobidzhan, especially given the long ago Communist affiliation of the magazine which he edits and which ran his encomium.

Zionists didn’t suddenly get greedy about having a state rather than a home, as Beinart wishes to believe. The change that happened with the rapid collapse of empires in the eastern Mediterranean and, for that matter, throughout the world was entirely external to Zionism. In Herzl’s Altneuland, Jewish self-determination may have been expressed as an autonomous district in a continental empire, but that’s the kind of thing you might think of in 1896. It’s also full of references to telegraph use. Is email a betrayal of early Zionist ideal as well?

A second thing happened that was external to Zionism: the genocide of the Jewish people in Europe in the early 1940’s. Beinart is certainly right that the Holocaust ‘fundamentally transformed Jewish thinking about sovereignty,’ though hardly in the egregiously tacky way he presents it (in a quote from historian Dmitry Shumsky) as a cynical ‘new contract.’

Nineteenth century Zionists couldn’t incorporate the fact of the Holocaust into their thinking because it hadn’t happened yet and they couldn’t possibly imagine that it might. No one could have before it happened. Very few could even while it was ongoing. Many still struggle today to fully comprehend it. But there really was a Shoah, and it would be unusual in the extreme for any kind of Jewish liberation movement to just look at that and say, ‘Right, well, that was certainly a bump on the road, but nothing there to cause any reassessment.’

That the industrialised mass murder of six million Jews made the need for a Jewish state feel more acute to those that survived isn’t some lamentable distraction; it’s an entirely realistic response, maybe even the only one. Herzl sought to establish a Jewish state (and he used the word state, however much Beinart tries to redefine it) by seeking at turns the sponsorship of the Turks and the Germans and the British. But even the Jewish National Home established by a League of Nations Mandate ultimately provided very little protection for Europe’s abandoned Jews. Only a state could do that, and it is entirely appropriate that this would be the Zionist conclusion. What Beinart leaves out of his discussion of a ‘Jewish home’ is that it is not a fresh idea or even a recovered old idea never tried. There was a Jewish National Home in Palestine from the 1920s right through the Holocaust itself. It was and remains perfectly reasonable for Jews to conclude that a ‘home’ is insufficient.

Finally, there was a third development in the early 20th century which upended Jewish life, and this one, even more than the emergence of a global sovereignty norm or the impact of the Holocaust, is the one Beinart most struggles to come to terms with. Antisemitism had always existed in the Arab world, to be sure. But a cosmic hatred of Jews as such a totemic feature of Arab political life is a twentieth century phenomenon. It has made its impact felt not only in the Israeli-Palestinian arena, but throughout the Middle East and throughout the entire world as Jews have been consistent targets for jihadist violence for decades.

This is such a central feature of Jewish life that it’s almost bizarre how easy it is to miss. But when your first intellectual commitment is to the notion that Jews act and Arabs only react, it’s easy to chalk up any anti-Jewish violence to revenge or anger about the occupation or the various defeats in Arab-Israeli wars. This is, to say the least, rather ahistorical. The rise of nationalist sentiment in the Arab world after World War I led to violence against minorities everywhere, and especially violence against Jews — almost exactly as it did in central and eastern Europe. The fall of multinational empires rendered minorities vulnerable everywhere, but the situation was particularly precarious for minorities who were nowhere a local majority.

Pogroms against longstanding Jewish minorities in the Arab world preceded the Arab defeat in 1948 and were carried out before there was even a single Palestinian refugee. Thus it was in Cairo, in Alexandria, in Aden, in Tripoli, and most notoriously in Baghdad. Protecting Jewish minorities in newly independent Arab states in the 1940s and 1950s was the manifest interest of all those states. It would have kept in Iraq and Tunisia and Yemen populations that were key drivers of economic development. It would have denied the hated Israeli state a demographic advantage just when one was necessary. And it would have suited the anti-Zionist propaganda claim that the Jews were merely a religious minority and not a people. But, of course, neither the mobs nor the regimes in charge could help themselves. If they genuinely believed that Jews were not a people and that middle eastern Jews had nothing to do with a European settler colonial enterprise in Palestine, then seeking ‘revenge’ against Jewish minorities wouldn’t have been the first instinct. And yet in country after country, that is precisely what it was.

There is not a Jewish community in the world that hasn’t been touched by the need to conform to the security demands that this hatred imposes. It has been decades since anyone visibly Jewish has felt entirely comfortable boarding a metro train or walking in all neighborhoods of a European capital. This is usually excused as blowback from a terrible conflict, which is odd since there are many diaspora communities from many different conflicts in Europe and the Americas (including conflicts where one side is Muslim and the other is not), and we don’t often see Armenian bakeries getting trashed or Greek Orthodox churches getting stoned or Ukrainian cultural festivals needing multiple perimeters of security each time there is a flare-up. We won’t begin to understand Arab antisemitism if we only insist on seeing it as an effect of the conflict rather than as one of its causes.

Before the contours of the conflict were widely understood, many early Zionists naively imagined all sorts of scenarios where Zionist goals were compatible with Arab nationalist aims. Jabotinsky himself dreamed of rotating Jewish and Arab prime ministers in a Jewish state. It’s notable that Herzl was actually much less naive than he is remembered. One of the subplots of Altneuland is the political campaign of a fanatical Jew seeking to deny Arab citizens their equal rights; he is ultimately defeated.

There were also Jews who argued passionately in this period for a kind of binationalism, like the one Beinart proposes now. Beinart refers to Brit Shalom, the main pre-statehood organisation dedicated to binationalism as evidence of an alternative path not taken, but never mentions that besides failing to convince more than a tiny minority of Jews of their cause, they were even more fatefully never able to find any Arab partner at all.

Beinart can’t see the contribution of this to Zionist thought because he is simply unable anywhere in any of his writing to assign any agency at all to the Arab side of the Arab-Israeli conflict. When I challenged him on this seven years ago, he rushed to defend himself with five putative counter-examples, all of which actually proved my point. But now, the mask has dropped and he no longer even pretends to meet the challenge, instead resorting to cheap sloganeering on Twitter that ‘ ‘You’re not granting Palestinians agency’ is hasbara for ‘You’re not blaming Palestinians for their own oppression.’ ‘

It’s such a recurring lacuna in his writing on his Israel that it must reflect a deeply held commitment on his part. He can’t see Arab or Palestinian choices, and he can’t see the cataclysmic hate for Jews in the Arab world as anything more than an effect of the conflict, rather than as one of its animating causes. Beinart is the Basil Fawlty of modern Mideast history, hissing under his breath to everyone to not mention the Arab antisemitism!

This isn’t just true for distant historical events either. To take just one minor example, Beinart describes the cause of the 2015 ‘stabbing intifada’ as ‘oppression meets hopelessness.’ But the spate of stabbings had a very clear cause behind them which Beinart prefers to ignore. They were incited by rumors of a Jewish attempt to damage the al-Aqsa mosque. There was nothing new about these rumors. For roughly a century now, rumors that Jews were conspiring to harm Muslim holy sites have been deployed to incite violence against Jews about once a decade.

This paranoid antisemitic conspiracy theory can be explained several ways — partly, it is obvious transference of what Arabs did to holy Jewish sites during the brief nineteen-year period in the mid-twentieth century when Old Jerusalem was under their control — but it cannot be explained by the occupation or even the existence of the State of Israel, since it was just as potent in fomenting anti-Jewish violence before 1948 as after. In fact, it was more effective before. In the 1929 pogroms, many more Jews were killed as a result of this conspiracy theory precisely because they lacked then what they have now: a sovereign state to defend them. Why does Beinart want to return six million Israeli Jews to this position of vulnerability again?

There’s something almost precious in the way Beinart asks ‘How did Zionism evolve from an ideology that encompassed alternatives to Jewish statehood into one that equates them with genocide?’ Because in order to pose such a silly question you’d have to be completely ignorant of all three of the historical developments alluded to above — one of which involves an actual genocide against the Jewish people and another of which involves the ecstatic and gloating promises of a genocide which were thankfully beaten back by Jewish arms in 1948 and 1967. Or, and this is more likely Beinart’s case, you would have to be so fully committed to a historical method that sees only Jewish causes for a conflict involving Jews and only Jewish neuroses as explanations for fears Jews might have for their safety that you are simply blinded to the weakness of your argument.

PRESENT: WHY NOT TWO STATES?

No surprise then that is the method Beinart applies to analysing how the two-state solution — something he once claimed to support — is no longer possible.

Beinart, to his credit, does not assign all of the responsibility for his change of heart to factors external to him. He openly admits that he also changed his mind. But the narrative behind his change of heart is a familiar one. We could have had two states, but then Israel went and settled the West Bank so much that we no longer can. People tend to believe this narrative when they really want to — that is, when they want to hold on to both the belief that a Jewish state shouldn’t continue to exist but also want the probable victims of Israel’s end, the six million Jews living there, to also be the ones held morally responsible for the state’s demise.

For anyone else it remains unclear why this narrative should be so convincing. If so many Jews moved from Israel to the West Bank in recent years, why can’t they just move back? Or, if Israel has a large Arab minority, why can’t a future Palestine have a large Jewish minority? The border might be complicated, but no more so than borders in other former conflict zones.

For Beinart’s argument to work, two things need to be true which are not. First, the prospect of two states for two peoples needs to have been possible at one time but no longer be possible now by some measurable metric. And second, it needs to be Israel’s fault that it is no longer possible.

Twenty-five years ago, during the Oslo peace process, developed areas of Israeli settlements took up less than 2 per cent of West Bank land. There were at the dawn of Oslo a total 118 settlements in the West Bank (figures are taken from Peace Now’s invaluable settlement database). In 2000, when Arafat rejected a peace deal that would have created a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, built up settlement areas were still just under 2per cent of West Bank land and the total number was 123. Today, the settlements still take up less than 2per cent of West Bank land, and the total number is somewhere around 127 (there is disagreement on what counts as a new settlement). The geographical distribution of Jews in the West Bank has not materially changed at all in the past 27 years (1993–2020), and that’s significant because it did change very dramatically in the 26 years before that (1967–1992) in ways that did have consequences on potential peacemaking. In particular, the seven years of right-wing Likud led government (1977–1984) saw 76 new settlements established, nearly two thirds of the total in the entire 53 years of the Israeli presence in the territory. This reckless building spree surely changed the geography of the West Bank rather dramatically in ways that arguably limited future diplomatic options (that was certainly the aim at least), but nothing like that happened during the Oslo years or since.

And just as the geography didn’t change very much in the past three decades, nor did the demography. The Jewish population of the West Bank and East Jerusalem has been steady at roughly 15per cent throughout the past three decades — again, after a dramatic increase in the previous three (from zero). The place where the demographic balance changed, interestingly, is inside Israel, where the Arab population grew in the same period from 17per cent to 22per cent, yet no one blames Arab Israelis for killing the two-state solution.

If a two-state solution was geographically and demographically possible in 1993, it was still possible in 2000. And if it was possible in 2000, it was still possible in 2008. And if it was possible in 2008, it was still possible in 2014, and it is still possible now. Nothing on the ground has changed in those years to affect the feasibility of partition except for the rapid disentanglement in the 1990s of the Palestinian and Israeli economies which until well after the First Intifada started in 1987 were fully integrated (on an appallingly unequal basis, it should be said) and mutually dependent — and this one change makes two states more, not less, feasible.

The argument that settlements killed peace is a familiar one, and it’s a tempting one for anyone who wishes to see an Israeli fault for any failure — settlements, after all, are deeply unpopular even among most of Israel’s international supporters.

But the argument doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. At least three times in the past generation there have been serious negotiations between Israel, the Palestinian Authority, and the United States about a peace deal involving two states. They were not theoretical, but rather involved maps and timetables and concrete arrangements for borders and security. Such talks took place in 2000–2001 (Camp David and Taba), 2007–2008 (Annapolis and Jerusalem), and 2013–2014 (back channels in London and elsewhere and then Washington). In all three cases talks broke down when the Palestinian side refused to accept a state as part of a peace deal that would mean an end of claims (fully recognising Israel, renouncing demands for resettlement of descendants of refugees from the 1948 war inside Israel, etc.). Yes, even the talks brokered by John Kerry between Netanyahu and Abbas ended with an American bridging proposal which was accepted by Netanyahu and rejected by Abbas.

What’s notable in all three failed attempts is how little the settlements ultimately mattered. In the first two cases in particular, there was an almost automatic Israeli willingness to embark on a broad evacuation of many isolated settlements on land that would become a Palestinian state. In the last two there was an explicit acceptance of the principle that settlements which would be annexed to Israel would be offset by land swaps. All three cases led to plausible borders no more tortuous than those that exist between other once warring neighbors without natural barriers.

Even Beinart’s claim that the growing population of Israeli settlers in the West Bank inevitably led to less territory for a prospective Palestinian state is false. Beinart may occasionally be alarmingly ignorant about the realities of the Arab-Israeli conflict, but here he is being knowingly dishonest.

The claim he advances is that with a growing settler population, Israel offered less and less land to the Palestinians for a future state. This claim has the double benefit of both laying all the agency at Israel’s door (‘Israel has redefined statehood to include ever-less territory’) and to put the blame on an unpopular Israeli action, namely settlement activity (‘as more Jews have settled in the West Bank, Israel has demanded that a Palestinian state include larger and larger Israeli carve-outs.’). What’s the evidence? As Beinart lays it out, in 2000, with the settler population (he is counting East Jerusalem) at 365,000, Palestinians could make peace with Israel at the cost of 9per cent of the West Bank, but by 2020, ‘with the number of settlers approaching 650,000,’ the Trump plan would have them concede 30 per cent of the West Bank.

But using more than two data points shows just how hollow the empirical claim Beinart is making here, as well as the larger claim about the causal process. It’s true that in 2000 the Palestinians rejected a state along the lines Beinart sketched out. But it’s also true that in 2001 the Clinton Parameters proposed a significantly smaller Israeli annexation of 5per cent, even though there were more settlers in 2001 than in 2000, and the Palestinians rejected this too. It’s also true that in talks at Annapolis in 2007, even smaller land swaps were mooted, but no deal was reached — and there were more settlers in 2007 than in 2001. In 2008, Prime Minister Olmert proposed a Palestinian state with a roughly 2 per cent land swap, and Palestinian President Abbas walked away. And yes, there were more settlers in 2008 than in 2007. The connection between the number of settlers and the contours of a two-state solution is not the one that Beinart posits. Fitting the curve on only two data points is radically dishonest.

Nor is Beinart’s claim that more and more Israelis are settling in the West Bank particularly robust. The number of Israelis settling in the West Bank has dropped rather dramatically in the past generation. In 1996, 6000 Israelis migrated from Israel into the West Bank; twenty years later in 2016 that number fell to only 2000. Nearly all the growth of Jewish population in the West Bank has been from births, not from ‘settling’ at all. Three fourths of the population growth in the last forty years has been in three settlement blocs which can be accommodated with land swaps of less than 5per cent of the territory (much less, even, if some of the rejected proposals are taken seriously).

Looking just at the past fifteen years, during most of which Israel was governed by a right-wing pro-settlement government, nearly all the population growth was concentrated in two ultra-Orthodox settlements with high birth rates, Beitar Ilit and Modiin Ilit, neither of which is affiliated with nationalist settler movement. I urge everyone to open up a map and look where those two are. One starts about 600 meters from the old armistice line and the other about 700 meters (about one third of a mile). The settlement enterprise may very be a moral and strategic catastrophe for Israel (I am convinced it is and have written about this often), but there is no sense in which Beitar Ilit and Modiin Ilit make drawing a line between a State of Israel and a State of Palestine impossible in any way. The settler movement and the nationalist right in Israel prefer that you not know the numbers and the lay of the land, for obvious reasons. Beinart, perversely, works just as hard to obfuscate this reality.

FUTURE: END OF THE JEWISH STATE

As the recent aborted annexation debacle showed, Israel cannot incorporate the West Bank into its sovereign territory and remain both a Jewish state and a democracy. To restate that in the affirmative: Israel can exist as a both a Jewish state and a democracy on something roughly resembling the provisional borders created by the 1949 armistice agreements. The final disposition of those borders will need to be determined, as final borders eventually are in all international conflicts, by peace treaties negotiated between the warring sides when both are genuinely ready for peace, or at least too exhausted for more conflict.

Peter Beinart, however, does not see this future as possible. Instead he imagines an alternative future based not on the boundaries of any armistice or proposed partition or natural boundary or even any Ottoman administrative division, but rather based on the very short-lived lines of the British Mandate, creating one country where two distinct nations with two distinct histories and two vastly different economies and cultures and international commitments would share the institutions of state power under the principle of what he calls ‘equality.’

Why should ‘equality’ stop there, though?

Whatever argument can be summoned to deny a border between a State of Israel and a State of Palestine can just as easily be marshalled against a border between a Beinartian State of Equality and its neighbour Jordan or its neighbour Lebanon. In both cases, the existing international boundary does not follow any historic Ottoman or Arab internal boundary. In both cases, the lines are drawn by imperial powers and with specific concern, ironically enough, for the Zionist project. For that matter, what is the deal with Lebanese independence anyway? So gauche and anachronistic. For decades Lebanon and Syria have functioned under the direction of one state’s prerogatives anyway. Put a ring on it and call it one state already.

The principle needn’t be limited to the Middle East. It’s not just Zionists, after all, who fell for the siren song of statehood rather than just ‘home.’ So too did, among other peoples, the Irish. Beinart makes much of a stylised and tendentious reading of the Northern Ireland peace process (this isn’t the place to refute it), but it’s not clear why there needs to be a separate sovereign on even part of the island. The whole Northern Ireland dispute would mean so much less if Britain and Ireland were one state based on equality. Sure, that might mean that the hard-fought freedom of the Irish people would be undone, but ‘evidence’ shows that they would probably be better off living under ‘equality’ anyway. The Baltic states, with their complicated ethnic compositions and obstreperously nationalist politics don’t really need independent sovereign institutions either, if you stop and think about it. Sure, citizens with a European standard of material and political life might not jump at the idea of being in a Russian-majority state, but that’s only because they are imagining the Russia of today and not realising that so much of what seems to ail Russia is justified bitterness at the way it has been treated. ‘Evidence’ certainly suggests that a State of Equality would temper some of the negative Russian behavior to minorities, which is anyway an overblown projection of fears from the last century. And before you go insisting that Latvians want ‘sovereignty’ and not just a ‘home,’ make sure you ask the 25per cent of Latvians who are Russian (to use the preening formulation beloved by Beinart).

But Beinart is not seeking to reverse Latvian independence or Irish independence or Lebanese or Jordanian independence. He only seeks to undo Israeli independence, and he’s frankly miffed that the benighted Israelis together with the bogeyman of his first forays into the topic, the ‘American Jewish establishment,’ resist his designs ‘despite the evidence that in an equal country Jews could not merely survive, but prosper.’

This casual use of ‘evidence’ is worth pausing on for a second. Beinart sees ‘evidence’ in unrelated and entirely incomparable cases (Belgium, for example) that Jews would be safe in an Arab-majority state, but doesn’t count the overwhelming evidence that they would not (for example, the uncomfortable question of why Jews don’t even feel safe in Belgium right now). He sees evidence that the two-state solution is dead thanks to Israeli action, even though on his own terms such a solution was equally plausible back when he was still claiming to support it. Most outrageously of all, he sees evidence, backed only by his febrile imaginings, that Israel is plotting to carry out a massive expulsion of Arabs from the West Bank and maybe even Israel itself, and urges an unrealistic and unworkable solution to a threat he has invented as the only way to stop it.

For Jews to be concerned about their fate under Arab rule is nothing more than neurotic Holocaust transference according to Beinart, an odd misreading of Arab rhetoric in the lead up to both the 1948 and the 1967 war. In contrast to that, Beinart detects a genuine Israeli plan to effect mass expulsion. The juxtaposition of Beinart’s two fantastical prophecies is remarkable, both for his gullibility and for how revealing they are about his prejudices about peoples he knows so little about except his own vain projections. The Arabs will treat the Jews in what was Israel just fine when they get power, but the Jews are secretly planning a mass expulsion when they get the chance. Can anyone who has looked at the lot of historic Jewish communities in Arab countries in the past century on even the best days or the behaviour of Israel in the occupied territories on even the worst ones take either claim seriously?

On Israel’s supposed plans for expulsion, Beinart intones, ‘that prospect is not as remote as it seems,’ and then in typical fashion produces only the flimsiest of evidence. First, as in 2013, there is a willful misinterpretation of an opinion poll used to cast Israelis as monsters. The option to ‘physically remove’ Palestinians from Area C is ‘the most popular answer’ among Israeli Jews, he writes, referring to a public opinion survey. But this is misleading for a number of reasons. The most popular answer is a small minority, as there were five responses. The question asks not what respondents want, but rather what they think should happen if Area C is annexed (including among the larger number who opposed the idea). And the verb used to describe this option doesn’t make clear whether it refers to moving people or transferring authority over the villages in question. Even under the least charitable interpretation, it doesn’t call for expelling anyone out of the country anyway.

That’s not all. Beinart then slips into the same paragraph the recurring proposal by some fringe Israelis (and not always on the fringes you might expect) to cede land on the Israeli side of the Green Line that is mostly populated by Arabs to a future Palestinian state in exchange for land east of the Line that is populated by Jewish settlers as further evidence for the budding acceptance of mass expulsion. While careful to first describe it accurately as a ‘redrawing of borders,’ he states its purpose is ‘to deposit roughly 300,000’ Arab citizens outside of Israel, and sandwiches the whole sentence in between claims that Israel is inexorably headed toward expulsion.

This is not the place to discuss the idea of such border adjustments. The idea is a bad and impractical one for myriad reasons and has never had any real traction in Israel. But there is something odd about the way it is framed here as portending an impulse to ethnic cleansing. If India today announced that it was willing to cede Muslim areas of Kashmir to Pakistan, would that be seen as a new form of intransigence or a new openness to compromise and concession? When an Israeli desire to hold on to certain land is your evidence of Israeli malevolence and an Israeli desire to withdraw from certain other land is your evidence of Israeli malevolence, maybe the problem has less to do with Israel and more to do with you.

It’s a remarkably disingenuous claim, made even more disingenuous by Beinart’s insistence on the façon de parler of Israel rejectionists in calling Arab citizens of Israel ‘Palestinian.’ If a chunk of land on the border is populated by Palestinians, why is a willingness to cede that land to a Palestinian state in a future peace agreement a ‘mass expulsion’?

It’s not a slip or an editing error. Like a tedious Ivy League sophomore explaining to the college staff that they should refer to themselves as Latinx (before asking to speak to a manager), Beinart insists on referring to Arab Israelis as ‘Palestinian’ though public opinion surveys consistently show that most reject this label (only 7 per cent prefer it, in fact, according to a recent poll, and the trend is downward).

He cites, for example, two surveys from the Israel Democracy Institute (full disclosure: I am a researcher there, but have nothing to do with public opinion polling) purporting to show more liberal attitudes in general among ‘Palestinian citizens,’ though when you click on both links, you discover that the word nowhere appears. The survey of Israelis distinguishes between Israeli Jews and Israeli Arabs, and Beinart’s sentence about the surveys, like the sentence before about a different set of surveys, would be clearer if he kept the same distinction, but it is obvious that for him introducing the word ‘Palestinian’ is a crucial part of the larger narrative he seeks to push of a fully formed Palestinian nation on clearly marked historical boundaries that was robbed of its rightful inheritance by Zionist usurpers.

The word crops in other dissonant contexts. He gives backhanded praise for the ‘honorable exceptions’ among early Zionists who were ‘concerned with Palestinian rights,’ naming Ahad Ha-Am, Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem, Judah Magnes, and Henrietta Szold, though none of them would have used that term because it was not then used to describe an Arab nation. He states that ‘Zionists employed violence against Palestinians,’ though when you follow the link he provides, you discover again that he is changing the terminology. (And the sentence construction is notable too: ‘Zionists employed violence against Palestinians’ to describe an attack in 1939 after three years of violence against Jews in Palestine, though if you were expecting him to refer to that by describing Arabs employing violence against Jews you clearly don’t know Peter Beinart: ‘increased Jewish immigration provoked increased violence between Palestinians and Jews’ he says of that episode; also, ‘in 1929 and 1936, Palestinian uprisings turned violent.’ Turned? From what?)

Whenever he needs a dyad for the parties to the conflict, he consistently reaches for the mismatched ‘Jews and Palestinians.’ It’s an odd pairing. If you are going to talk about the conflict as a whole, you might talk about the Arab-Israeli conflict. If you are going to talk about the two peoples fighting over the same land as ethno-religious communities — particularly if you are talking about the Mandate period — you might talk about ‘Jews and Arabs’ and the proposed Jewish and Arab states of the various partition plans from 1937 to 1947. If you are talking about national-political communities, you might call them ‘Israelis and Palestinians.’ But for Beinart it is always Jews and Palestinians. On the first or fourth or even fifth time he pairs these terms, you might not notice what’s happening.

But after about a dozen the agenda is unmistakable. Just as Beinart can’t describe a set of events, especially a lamentable one, as anything other than something with a Jewish or Israeli subject and a passive Palestinian object, so his relation to the two competing national movements evinces two opposite pressures. The yearning for Jewish sovereignty in a historic homeland is something new, transient, and artificial; it’s not a longstanding goal but a perversion of an earlier desire for an amorphous ‘home’ that has been distorted by displaced Holocaust trauma. But the national movement of the Arab Palestinian people — that is eternal. Beinart sees Palestinians in history even where no one was claiming that title, and if he doesn’t see them in the text, he writes them in. Beinart sees Palestinians in the Arab community in Israel, and if they don’t see themselves there, he will call them that until they accept it.

This is more than just an awkward Starbucks cup making it into a shot of Game of Thrones. It’s a tendentious ransacking of history of the Arab-Israeli conflict so thorough that by the end the whole thing reeks of pumpkin spice.

And it’s at the core of his territorial argument too. Palestinians, in his telling, had ‘already settled for a country in 22 per cent of the land’ and would settle for no less. Let’s leave aside that this is empirically false, and that subsequent peace talks broke down on demands for ‘return’ refugees into Israel and a refusal to accept a Jewish state as a neighbor — in other words, demands far outside the supposed 22 per cent.

Let’s consider instead how odd this argument would sound in any other context. Accepting Israel’s existence in 78 per cent of the land of the Mandate isn’t a concession to Israel. Israel is there; it already exists. It’s a concession to reality. Not even 1 per cent of that 78 per cent was ever a Palestinian state of any kind. Zionists too once claimed both halves of the British mandate, including what is today Jordan. But the British exercised the option granted them by the League of Nations to exclude Transjordan from the Jewish National Home in 1922, cutting off 77 per cent of the territory from Jewish land purchases and settlement.

So is a Jewish state on everything on the west side a ‘concession’ that whittled down the state to 23 per cent of its historic claim? Some right-wing Zionists did make this argument, by the way, but it has never been taken seriously outside these rarified circles. In fact, in no negotiation situation is acknowledging what your rival already has that was never yours considered a concession, much less a final concession that one side gets to stipulate for itself peremptorily.

Lots of national liberation movements, in fact, have historical claims on lands they don’t control anymore and can’t obtain through force or negotiation. Accepting such unmet claims has often been a painful stage of liberation for many post-imperial states, such as Poland, Greece, Armenia, Ireland, and, for that matter, Israel. In none of those cases is there a bogus argument made involving an exact percentage, because each of those cases involve long complicated histories on ambiguously delimited territories over different times and conflicting memories leading to liberation, rather than just a very recent negation of someone else’s liberation.

The Irish case is actually exceptional here, because there is an actual island that exists as a geographical fact prior to any political division. But even here, one doesn’t often encounter exact percentages of land supposedly lost or conceded (though one does encounter lots of bitterness about partition, but that is hardly unique).

But while Ireland north and south could be conceived of as a discreet territorial unit, the land that together comprises Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip can only be conceived as a similarly discreet unit by ignoring all the various borders that have existed there in the past and might exist in the present and insisting on only one set that existed very briefly from about 1922 to 1948 — that is, of the British Mandate, not any Arab state but rather a League of Nations mandate for the establishment of a Jewish National Home. (Pause on all that irony if you need to.)

For Beinart, though, it is essential to conceive that as one geographical entity, otherwise there is no explanation for why ‘equality’ can’t apply across the West Bank-Jordan border, or the Syria-Lebanon border, or the Gaza-Egypt one. He concedes there is no acceptably neutral name for the country as a whole that he wants to impose his ‘equality’ vision onto, so whenever he wants to refer to it he uses some variation of ‘between the river and the sea,’ with reference to the River Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea, but this too only reveals the artificiality of the whole claim.

From north to south, Israel is about 425 kilometers long. Only about 125 kilometers of that has a river to the east and a sea to the west. This is the part that has all the historically heavy places that were often labelled on historical maps as Judea or the Holy Land or Palestine. And this is part of the country where, if a two-state solution ever does come into being, the overwhelming majority of the land will be part of the Arab, not the Jewish state.

Even if you take into account the two lakes as part of a natural eastern border and add into the river-and-sea portion, you still only get about 210 kilometers — just under half the entire length of the country. Why is that? Well, the entire southern half of the country is the Negev desert, where the eastern and western borders are lines in the sand drawn over the course of history as a result of wars, peace talks, imperial interventions, and international resolutions, where things like battle outcomes, strategic interests (for example, access to seaports), and ethnic makeup are considerations in the outcome. Each is a border just like any other in the world — an outcome of history. The Arab population that lived in the Negev before 1948 had very little to do both in terms of dialect, dress, customs, religious practices, and even physical appearance with the Arab population in the rest of the country that would come to be called Palestinian.

In the north something similar — history — happened, but with very different results. The border that today separates Lebanon and Israel was agreed upon by the French and British as a border separating the French Mandate for what was designed to become a future Arab Christian state from the British Mandate for a Jewish National Home. It is a jagged line drawn right through the middle of what was an Ottoman province, jagged because contrary to the stereotype of how colonial borders were drawn, this one was effected with attention to the property claims of villagers on either side of the line. Equally notable, every effort was made to respect the ethnic purposes of the two mandates — wherever possible Christians and Shiites are north of the line and Jews are south of it. This is how you get the so-called Galilee Panhandle, where the western border is not a sea but rather a mountain ridge separating an area of Jewish settlement on the east from one of predominantly Shiite settlement to the west.

It’s such a transparently bad basis for any historical claim, but Beinart finds it compelling because it coheres with his selective and rather curious sense of history.

There is also a curious ethical sense of national responsibility. Remember, Beinart believes that the blame for the eclipsing of the two-state option is entirely Israel’s to bear — never mind that he is, as demonstrated above, both wrong about two states not being an option and wrong about Israel bearing responsibility for the failure to realize that option. Jews were entitled to an independent state in part of their historic homeland, in Beinart’s telling, but by their own misguided actions they forfeited that right, now and for future generations (and American Jews — but not Beinart! — are ‘complicit’).

Interestingly, this ethical sensibility simply doesn’t apply for the Palestinians. The support for Hitler, which Beinart dismisses as “tragic,” may have had consequences for other nations (with much more difficult circumstances and dilemmas, such as Finland among others), but it is impolite to even mention it in this case. The rejection of the Partition in 1947 shouldn’t have consequences. The Arab defeat in 1967 shouldn’t have consequences (22% is the last concession, recall). And the abuse of the Oslo process for a campaign of suicide bombing which only accelerated after the rejection of serious peace offerings from Israeli and American leaders should absolutely not have any consequences for Palestinian claims for territory or anything else from Israel. Israel’s guilt is (excuse the obvious theological precedents) passed on down the generations; but the Palestinians operate on a moral tabula rasa where only eternal victimhood is preserved. This is an ethical program without parallel or precedent anywhere in international relations.

There is so much more dishonest revision and pious posturing in his article that one doesn’t know what to leave out: the ahistorical claims about Arab political goals in pre-1948 Palestine, the shallow psychoanalysis that projects Jewish Holocaust trauma on Palestinians rather than taking seriously the violent Arab rejection of Israel, the selective and dishonest retelling of the PLO’s ‘recognition’ of Israel and the even more dishonest claim about Hamas’ ‘repeated embrace’ of a state next to rather than instead of Israel, the cloying quotes from Arab leaders that they would ‘safeguard the rights of vulnerable Jews’ under the utopian future Beinart dreams (thanks but no thanks). Most nauseating of all is the passage at the end where Beinart conjures a rabbi reciting El Maleh Rachamim at a Nakba memorial as a complement for a Holocaust memorial service. I know this is supposed to be utopian, but I had no idea utopia could be so grotesque.

And Beinart is supposed to be a serious Jewish intellectual, or even a modern-day Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai only asking for Yavneh and its sages. But no one who wallows in such moralizing cosplay while intimating such an appalling analogy between, on the one hand, the Arab experience of defeat in an attempt to commit ethnic cleansing and genocide of Jews and, on the other hand, the Jewish experience of actual genocide which had only just finished three years prior, deserves to be taken seriously.

A very interesting and intelligent article. Just one quibble: the author says that most Israeli Arabs reject the label of “Palestinian,” but this Reuters report from two years ago says just the opposite: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-israel-palestinians-nakba-identity/in-israel-members-of-arab-minority-embrace-palestinian-identity-idUSKCN1SF20R. This doesn’t mean that this Reuters article is necessarily right, but I wonder what’s behind the discrepancy.