Hamutal Gouri participated in the response of Mothers Against Violence to settler violence in the Palestinian village of Mufakra. She calls for a greater appreciation of the value of universalist, humanist and feminist approaches to ending the violence of some settlers against Palestinian civilians in the West Bank.

Burin

On 21 January, a Friday afternoon, a group of 20 masked Jewish young men from the illegal Giv’at Ronen outpost near Nablus, attacked with sticks and stones a group of senior Israeli citizens who came to help the residents of the Palestinian village of Burin to plant olive trees on their lands. They then torched the car of one of the activists. Footage of the wounded human rights activists – some old enough to be the grandparents of their attackers – quickly reached social media outlets. Several members of the government coalition from the center-left issued condemnations. Foreign Minister Yair Lapid said: ‘The police will investigate and prosecute the criminals, and we need to educate and have an in-depth dialogue about neighbourly relations, the rule of law and how we want to live here’. Several weeks following the attack in Burin, at least three residents of Giva’t Ronen were detained and several others received restraining orders from the area for two weeks. Public condemnations by senior public servants are of utmost importance, especially when followed by legal actions against the perpetrators of violence, be it against Jewish-Israeli human rights activists or against Palestinians.

Some right-wing members of the coalition tweeted copy-paste statements along the lines of: ‘while such behavior is to be condemned, one should not make generalizations against all settlers, they are pioneers, the salt of the earth.’ These politicians of course did not use the term ‘settlers.’ Rather, they used the Hebrew term Hityashvut Tse’ira – meaning ‘young settlement – echoing the nostalgic notion of the budding pioneers who came to the land of Israel to make the parched land bloom. The purpose of the attack was to disrupt the olive tree planting, a sign of ownership over the land.

On 18 January 2022, Israeli Ambassador to the UN Gilad Erdan gave a speech at the Security Council on stone-throwing attacks by Palestinians on Jewish residents of the West Bank. Holding a large stone in hand, Erdan said: ‘If a rock like this would hit your car while you drove home with your children, wouldn’t you think this is a terror attack that must be condemned?’

An Israeli journalist tweeted, quoting Erdan, and as is always the case, replies were quick to come, with tweeters asking: ‘did he also speak of terror attacks by Jewish settlers on Palestinians’? Well, he didn’t.

Like many politicians in Israel, Erdan wishes to hold the stick at both ends: to be the sovereign in the occupied territories – with the power to make decisions and take actions that impact the lives of nearly three million Palestinians – but to also be the victim in the enduring conflict. Admitting to violence perpetrated by some Jewish settlers does not serve that purpose.

Having stones thrown at your car, or your home, with your family in it, is a living nightmare, whether you are Jewish or Palestinian. The human and moral thing to do is to hold all lives as precious, and to care about the fears and anxieties of all children. One can say Erdan was trying to make a point in a setting perceived as hostile to Israel, but settlers’ violence does exist. Even mainstream politicians and journalists now admit it.

Mufakra

On 28 September 2021, the last day of the Jewish holiday of Sukkoth, also known as Simchat Torah, celebrating the end, and beginning of a year-long reading of the Torah, a group of masked men, including teenage boys, came from the Avigail outpost in south Hebron hills and headed to Mufakra village. They smashed the windows of homes and cars, punctured tires with knives and even went after the livestock as well. They injured a three-year-old toddler and left the children of the small village terrified. The following day, mainstream Israeli media covered the event. The story of settlers’ violence against Palestinians in the south Hebron hills reached many Jewish Israelis for the first time.

The images of a wounded toddler may have, for the first time, cracked the general atmosphere of indifference permeating in the Israeli public when it comes to the suffering of Palestinians. The violence towards the inhabitants of the Mufakra village finally got the attention of a broader audience.

A few weeks later, Public Security Minister Omer Bar-Lev, in a conversation with senior US officials, said that settlers’ violence was a real problem that must be reckoned with. Prime Minister Bennett was quick to reprimand his own minister and voice his support for the Jewish residents of the West Bank: ‘Settlers in Judea and Samaria have suffered violence and terror, daily, for decades,’ Bennett tweeted, ‘They are the bulwark for all of us, and we must strengthen and support them, in words and actions.’

It wasn’t clear whether Bennett was angry with Bar-Lev airing Israel’s dirty laundry with the Americans, or his supposed lack of empathy for the violence endured by Jewish settlers. Perhaps it was both. Yet the question remains: does Bennett believe that settlers’ violence is indeed ‘insignificant,’ or does he believe it is justified? When one accepts or ignores settlers’ violence towards rural Palestinian communities by pointing the finger at violence by Palestinians, one does not condemn violence as such. It amounts to saying that violence is justified if it serves national strategic goals. That settlers’ violence against Palestinian rural communities is acceptable or can be ignored because it serves a strategic purpose.

The Data

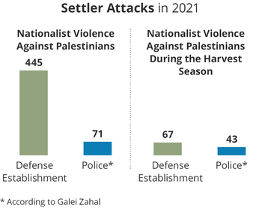

Either way, the issue of settlers’ violence gained prominence in the political discourse. Mainstream media outlets released follow-up investigative pieces, and reporters began to search for and publish data aggregated by IDF, the police, and human rights groups. But even state agencies, the police, on the one hand, and the IDF and Shin Bet, on the other, are not in agreement regarding the scope of the problem. The data, as some journalists stated, serves both camps: those who claim that settlers’ violence is ‘insignificant,’ and those who claim it is real, and presents a moral and security issue that Israeli society must reckon with.

[Credit: Ha’aretz Website]

[Credit: Ha’aretz Website]

As is always the case, facts and narratives are disputed in the context of the decades’ long controversy between those who support the settlement project and the occupation, and those who oppose it.

Controversy is celebrated in the Jewish tradition by Talmudic sages if it is ‘for heaven’s sake,’ meaning, in search of the divine truth, or to get to the bottom of a complex question. Dialogue, the exchange of views and interpretations is still practiced in the service of creating knowledge, embedded in the belief that we grow – spiritually and intellectually – from controversy. Yet, the political controversy over the occupation – and settlers’ violence as its by-product – is going nowhere, and the numbers – no matter who you chose to believe – won’t change that.

When one magic word – security – reigns supreme over the conversation, it designates as traitors those who condemn acts of settler violence and point towards the incremental damage done by the proliferation of illegal outposts in the West Bank. And if the debate is once again a zero-sum game of opposing political views, is there breathing room for universal and Jewish values of morality, compassion, and non-violence? When you look at a conflict through the narrow lens of a gun barrel, caring is perceived as a weakness, not a strength. That is why we need to transform the conversation.

Mothers Against Violence

With this in mind, on a pleasant autumn Saturday a few days after the settlers’ attack on the village of Mufakra, a group of women activists from ‘Mothers Against Violence’ joined a visit to the village. The male leaders of the community took us on a brief tour of the small village, so that we could see for ourselves the damage caused to homes, cars, and water pipes. We brought toys and sweets for the children. The terrified looks on their faces, and the tears that sat in their eyes until the adults told them we were human rights activists, has lingered with me. We then asked to meet with the women of the village. Sitting together at the village’s gathering place, we asked them how we could help. ‘Help us tell our story, so that people will not forget,’ one woman, her children huddled next to her, told us.

As a storyteller for social change, I was deeply moved by her response. I just started reading Maria Tatar’s new book, The Heroine with 1001 Faces, a belated feminist response to Joseph Campbell’s best-seller, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which to this day informs how male protagonists are created and depicted. Tatar takes on a much-needed project; to trace and conceptualise the qualities and traits of female heroines as distinctly different from those of male heroes. Without access to weapons or even writing instruments, and often silenced, women have fought back against violence by telling stories. As Tatar beautifully puts it, the qualities that best describe female heroines in the corpus of myth, folk and fairy tales were curiosity, caring deeply for the world and its inhabitants, and a commitment to social justice. One poignant example is the heroine in the ‘Bluebeard’ tale and its many variations, where the heroine manages to escape a brutal death by telling her story. From a victim of gender-based violence she becomes an agent of change, and, in some version, revives and heals the victims of femicide perpetrated by Bluebeard.

We, the mothers against violence, along with some male allies, visited the village a few weeks later. This time, the children recognised us for our yellow vests, and their curious looks turned into cheerful smiles as we played silly games together. They felt safe in our company, under the watchful eyes of their mothers.

On our way back, we saw two heavily armored young soldiers. We asked them what they were doing there, noticing the impact of their presence on the village kids. Their response was ‘reducing conflicts.’ We wanted to ask them why they didn’t ‘reduce’ the attack on the village a few weeks earlier. Or why video often shows them standing idly by during similar settlers’ attacks. But we didn’t. These young soldiers in active obligatory service had no choice but to be there. The orders came from above, and although they were older than the kids in the village, they, too, had mothers and fathers who worried for their safety.

People say that if only the mothers on both sides of the conflict came together, united by their passion for their children’s safety, we would have figured out a just solution. I would like to believe this is true. I want to believe that applying a caring and critical gender sensitive lens, one that sheds light on the unique ways in which women, children and youth are affected by a violent conflict, may shift the conversation. I believe that if women from both sides who cared for their communities were actively and equally involved in peace talks, the results would be different. But first, we must have peace talks, which is a topic for a separate article.

Adrienne Rich wrote in her poem, Sources: ‘It is only now, under a powerful womanly lens, that I can decipher your suffering, and deny no part of my own.’ It is a powerful response to the ‘whataboutism’ that permeates the public debate on settlers’ violence against Palestinians. It offers a whole different space that makes room for human suffering and for multiple voices and perspectives. It allows us to consider the horror of a Palestinian mother desperate to protect her children, and the horror of a Jewish mother, desperate to do the same.

Stories of suffering, resilience, and hope were often dismissed as ‘old wives’ tales’, simply because they were told by women. The sexist notion that women were frivolous, too emotional, or simply not knowledgeable enough to discuss ‘serious matters’ is still very much with us. Sadly, this means that the powerful content of stories – referring to real dangers, threats, and injustices – is lost because of the gendered identity of their tellers.

Sharing stories of suffering, resilience, and hope is essential to peacebuilding. Caring deeply for those around us – regardless of national or racial identity – is a form of heroism. Seeking just solutions to a bloody conflict that engulfs us all in a vicious cycle of violence is a moral imperative for all of us.

As an outsider, it is impossible to fully understand the dynamics of ‘on the doorstep’ incidents such as the cited attack by settlers. However, unless the authorities respond in an evenhanded manner to what seems to have been a criminal act of violence against fellow citizens (irrespective of ethnicity) the incident will provide a photoshoot opportunity to the extremists for recruiting purposes and provide ammunition to those international political/media factions that are already hostile to the Jewish position and risk losing goodwill from non-aligned friends of Israel.