Oren Kessler reveals the secret 1937 testimony given by David Lloyd George to the Palestine Royal Commission. Lloyd George had been prime minister during the 1917 Balfour Declaration, and had remained an unswerving Zionist ever since. He was one of nearly 60 witnesses whom the panel heard in private, and whose testimonies have been kept secret for eight decades. His appears here for the first time; it depicts a boisterous, at times embittered septuagenarian defending the Balfour Declaration on grounds of wartime strategy, and the need to appeal to worldwide Jewry, ‘a dangerous people to quarrel with,’ and ‘a very subtle race.’ Lloyd George was at once ‘Judeophobe and philo-Semite, militarist and appeaser, Zionist champion and Hitler enthusiast’ argues Kessler, author of Fire Before Dawn: The First Palestinian Revolt and the Struggle for the Holy Land, forthcoming from Rowman & Littlefield.

THE REMOTE FUTURE

The Palestine Royal Commission was appointed in summer 1936 to probe the causes and possible remedies of a six-month Arab rebellion that had inflicted £3.5 million in damages, and cost the lives of 80 Jews, 28 Britons and hundreds of Arabs. Its report a year later was a watershed in the Mandate, establishing the ‘two-state solution’ as the template for settling what had become an unignorable national dispute. And yet remarkably, scholars have paid relatively scant attention to the witness testimony that led the commission to a scheme so bold and risky (see Part 1 of this essay, ‘A “Clean Cut” for Palestine: The Peel Commission Reexamined’ in Fathom, March 2020), and one that eight decades later continues to enjoy a broad diplomatic consensus.[1]

Chaired by Lord William Peel, the panel heard 60 witnesses in public sessions – transcribed, collated and published alongside the report by His Majesty’s Stationery Office. But nearly the same number testified in secret[2] — so secret that even the witness list itself was hidden, and witnesses barred from appearing with prepared notes. Transcripts of the sessions were recorded solely for the commissioners’ use and might have been lost or destroyed had not their far-sighted secretary recognised their significance. Delivering them to Whitehall for safekeeping, he scribbled in the initial blank pages that a few copies ought be preserved, as they chronicled ‘an important chapter in the history of Palestine and the Jewish people, and will, no doubt, be of considerable value to the historians of the remote future.’

Exactly eight decades into that remote future, in 2017, Whitehall quietly released them to the National Archives at Kew. Only one scholar, Laila Parsons, has so far dipped her toe into the more than 500 oversized pages of small, densely written, twin-column text.[3]

The secret witnesses included the upper crust of the Mandate – administrators like High Commissioner Arthur Wauchope and two of his predecessors, as well as the chief immigration officer and the commander of British forces in the country. They also included Chaim Weizmann, president of the world Zionist Organization, and David Ben-Gurion, chair of the Jewish Agency for Palestine (Arab witnesses – who boycotted most of the proceedings after London refused to halt Jewish immigration – insisted all their own testimony be public).[4] The penultimate testimony, heard after the commission’s return to London, came from David Lloyd George, who had been prime minister during the Balfour Declaration, announcing the Crown’s backing for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, exactly two decades before.

‘ONE OF THE GREATEST HEBREWS’

Lloyd George had been an unflinching Zionist since the Great War. His first acquaintance with the movement came in late 1914, while still Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the person of Weizmann. He was neither the first nor last British official seduced by the charisma of the Russian-born chemist and Zionist activist, and his Baptist upbringing predisposed him to the latter’s vision: ‘When Dr. Weizmann was talking of Palestine he kept bringing up place names which were more familiar to me than those on the Western Front.’[5]

Lloyd George was soon appointed Minister of Munitions, at a time Allied armaments were in dire supply. Alongside First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, he grew fascinated by Weizmann’s experiments in fermenting common starches like corn and rice into acetone, and then to the explosive material cordite. The Admiralty built him a laboratory in London, and the experiments proved a rollicking success – distilleries were established across the British Isles, France, Canada, America and even India.[6]

Weizmann was ‘one of the greatest Hebrews of all time,’ Lloyd George later recalled, ‘applying his scientific skill and imagination to save Britain from a real disaster … In addition to the gratitude I felt for him for this service, he appealed to my deep reverence for the great men of his race who were the authors of the sublime literature upon which I was brought up.’

In late 1916 Lloyd George was elected prime minister, and as foreign secretary named Arthur James Balfour – Churchill’s successor at the Admiralty and a former premier himself. Lloyd George wrote that like himself, Balfour was taken in by Weizmann, ‘won over completely by his charm, persuasiveness and his intellectual power.’ [7]

The motives for Balfour’s eponymous 1917 Declaration formed the heart of Lloyd George’s secret Peel testimony twenty years later. He had recently completed the last of his nine-volume memoirs of the Great War and used the section on the Declaration as the basis for his prepared remarks (the commission apparently exempted him from their ban on pre-written statements). His tone was unrepentant and combative – he was now a septuagenarian MP from North Wales of waning political relevance – even more so as his prepared text gave way to unscripted, impromptu answers. His greater admiration for Jews than Arabs is unmistakable, but so too are evaluations of Jewish power and cunning that if uttered today would end the most distinguished career.

A PECULIAR EXPLANATION

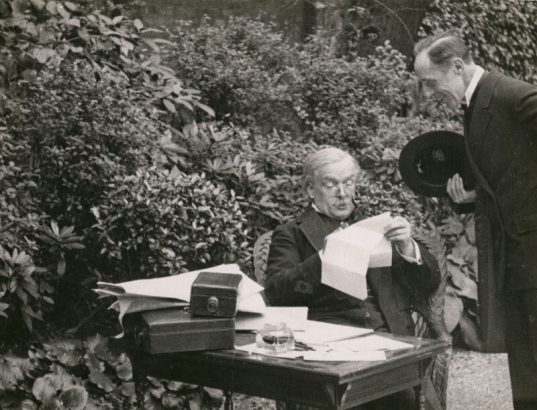

Lloyd George met the commissioners in London in April 1937, eight months after they had begun their study and three months before releasing their report.

‘I should like to remind the Commission of the actual war position at the time of the Balfour Declaration,’ he began. ‘We are now looking at the War through the dazzling glow of a triumphant end, but in 1917 the issue of the War was still very much in doubt.’ The Russians, French and Italians were all defeated, demoralised and exhausted, he said. German U-boats had sunk millions of tons of Allied shipping from America and elsewhere. The Americans had recently entered the war but were still not in the trenches. Public opinion in the United States and Russia were crucial, ‘and we had every reason at that time to believe that in both countries the friendliness or hostility of the Jewish race might make a considerable difference.’

If Balfour had not issued his Declaration that November, Lloyd George suggested, the Kaiser might have beat him to it. It was made just days before the Bolshevik Revolution, and Germany was ‘equally alive to the fact that the Jews of Russia wielded considerable influence in Bolshevik circles. The Zionist Movement was exceptionally strong in Russia and America,’ he said – a vast exaggeration for a what was still a fringe, aspirational ideology – and the Germans were sparing no effort to court it. For nearly three years both warring blocs had striven to blockade the other’s supplies, and a Russia friendly to the Central Powers ‘would mean not only more food and raw material for Germany and Austria, but fewer German and Austrian troops on the Eastern Front and therefore, more available for the West.’[8]

Immediately following the Declaration, ‘millions of leaflets were circulated in every town and area throughout the world where there were known to be Jewish communities. They were dropped from the air in German and Austrian towns, and they were scattered throughout Russia and Poland. I could point out substantial and in one case decisive advantages derived from this propaganda amongst the Jews.’

In this telling – in which the ‘Bolshevik’ and ‘Jew’ were virtually interchangeable – Balfour’s pledge directly prevented the movement of enemy’s food, arms and men, even after the new communist government signed a separate peace taking itself out of the war.

‘In Russia the Bolsheviks baffled all the efforts of the Germans to benefit by the harvests of the Ukraine and the Don, and hundreds of thousands of German and Austrian troops had to be maintained to the end of the War on Russian soil, whilst the Germans were short of men to replace casualties on the Western front. I do not suggest that this was due entirely, or even mainly, to Jewish activities. But we have good reason to believe that Jewish propaganda in Russia had a great deal to do with the difficulties created for the Germans in Southern Russia… the Jews in their subtle way managed to place every obstacle in the way of the Germans.’[9]

It was a highly specific, idiosyncratic explanation for a Declaration with worldwide, century-long implications, and one unlikely to persuade Palestine’s Arabs to willingly accept minority status.

But Lloyd George continued unfazed. Balfour had died in 1930, and now the role of Declaration spokesman fell to him.

Balfour did not envision the immediate creation of a Jewish state regardless of the wishes of Palestine’s majority, he said. ‘On the other hand, it was contemplated that when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunity afforded them by the idea of a National Home and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish Commonwealth.’ Any notion of artificially restricting that growth ‘never entered into the heads of anyone’ engaged in the policy and would have been regarded as a ‘fraud’ upon those whom the Declaration addressed.[10]

‘What about the Arabs? The Arabs have done well out of the allied victory. No race has done better out of the fidelity with which the Allies redeemed their promises to the oppressed races,’ he proclaimed. Owing chiefly to British and Allied sacrifices, the Arabs now had four independent states – Iraq, Syria, Transjordan and Saudi Arabia – ‘although most of the Arab races fought throughout the War for their Turkish oppressors.’

‘The Palestinian Arabs fought for Turkish rule,’ he emphasised, disregarding the 2,000 who had joined the British-sponsored anti-Ottoman revolt led by Hussein, Sherif of Mecca, and his son Feisal. Through Mark Sykes (of Sykes-Picot fame) and T.E. Lawrence (‘of Arabia’), he said, Britain informed Hussein and Feisal of the planned Declaration.[11]

‘We could not get in touch with the Palestinian Arabs as they were fighting against us. The Arab leaders did not offer any objections, so long as the rights of the Arabs were respected,’ Lloyd George explained. ‘There was a twofold undertaking given to them, that the establishment of a Jewish National Home would not in any way, firstly, affect the civil or religious rights of the general population of Palestine; secondly, would not diminish the general prosperity of that population. Those were the only pledges we gave to the Arabs.’

The ex-premier challenged any critic of Britain’s Palestine policy to point to an instance in which non-Jewish civil or religious rights had been compromised, and he marshalled statistics on revenue, exports, wages, land prices, public health and a half-dozen other indicators of the land’s newfound prosperity. ‘There can be no doubt that the Arab population of Palestine has profited enormously by the Zionist enterprise.’[12]

Chairman Peel asked if Balfour’s proclamation meant the Jews could ‘come in pretty nearly as they like,’ regardless of any negative effects on the Arabs.

‘Yes,’ said Lloyd George. ‘There is no doubt about that, from the words used by Lord Balfour, that it was contemplated by him that, in the course of political evolution, the Jews would have a majority.’ He said President Wilson, who had given his assent to the Declaration and made similar comments about a future ‘Jewish Commonwealth,’ felt likewise.[13]

A possible recourse, one commissioner offered, was ‘to try the idea of division…’

‘That is surrender,’ Lloyd George interjected. ‘That is going back on our declaration.’

The British Empire seemed to be losing its nerve, he complained. He was the only Welshman ever elected premier, and ‘as an old Briton, who belongs to the most ancient race in the islands, I do not like it.’[14]

INTERNATIONAL FORCES

It was a paradox that for many British gentile Zionists, philo-Semitism so often commingled with its antithesis.

So too for Lloyd George, in whose mind Jews pulled the levers of both world banking and Bolshevism. He claimed unnamed ‘Jewish financiers’ in America had placed serious obstacles to it joining the war during its first three years, and noted the choice of Rufus Isaacs, Lord Reading, to head a delegation there to secure what was then the largest bank loan in history: ‘we sent a Jew over to negotiate our loan, Lord Reading, and I do not think anybody else could have done it.’

The war planners, he said, had ‘wanted the help of the Jews’ and decided they ‘could either hinder us or help us very materially, because they have communities all over the world and they are a dangerous people to quarrel with, but they are a very helpful people if you can get them on your side.’ [15]

After the Armistice, hundreds of thousands of Polish and Russian Jews made their way west, fleeing pogroms and the regional wars that followed the Soviet Union’s birth. ‘[T]he Germans took a great many of them and they caused trouble there,’ Lloyd George ventured. He did not elaborate, but the equation of Jews with communist agitators seems the likeliest intended drift.[16]

Again he reprised the theme of the Jews’ vast, inscrutable power. ‘There are two people I would not quarrel with if I was running a State. They are both international forces; one is the Jews,’ he said (the other, reflecting his Protestant prejudice, was the Catholic Church). ‘They are a very subtle race and they have means of communicating throughout the world which nobody seems to know about.’[17]

DISAPPOINTMENT

Three months after Lloyd George’s testimony, the commission published its report. At over 400 pages, it is an elegant, painstaking and credible account of the Mandate’s birth, its fulfilment and its chance of survival. But history remembers it primarily for its final 16 pages, in which it recommends Palestine’s partition and briefly outlines borders and other arrangements for carrying it through.

Most mainstream Zionist leaders, led by Weizmann and Ben-Gurion, were thrilled by the prospect of a Jewish state, even as they strategically feigned disappointment (both viewed the scheme as a springboard for sovereignty, not the last word on borders). But for Lloyd George, the report was an unmitigated betrayal.

‘The Palestine Report is a deplorable ending to one of the most imaginative and promising experiments which the Great War made possible,’ he wrote in the Sunday Express. The national home ‘is to be mutilated and left to shamble along, a disfigured and shapeless cripple.’

The Jews, he wrote, not only fulfilled their end of the bargain, but seem to have done it too well: ‘Trouble has arisen entirely from the magnitude of their success.’ They have drained swamps, he said, birthed industries, and multiplied the country’s revenue and trade. ‘They have built Tel Aviv, a modern city of 150,000 inhabitants which … will rival any town of its size on the shores of that great inland sea.’

What will sixteen and a half million Jews, dispersed over the globe, think of this proposal to break a solemn pledge, he wondered. They were being offered a ‘mutilated Canaan, without Zion, Bethlehem or Judea…. a Jewish home without Judea – Zionism without Zion. They will return to their promised land to find a promise broken by those who gave it.’ [18]

POSTSCRIPT: ‘A JEW IS A JEW’ – HOW LLOYD GEORGE MISJUDGED HITLER

Lloyd George stands, alongside Balfour and Churchill, among the British statesman most committed to Zionism and most honoured in the Israeli memory. But he is the triumvirate’s junior member. Balfour Street in Jerusalem is home to the Prime Minister’s Residence, and Churchill Avenue is the main thoroughfare leading to Hebrew University and the British Military Cemetery on Mount Scopus. By comparison, Lloyd George Street lies in an unassuming residential corner of the German Colony quarter.

Here too history may be a guide. Churchill immediately recognised the 1933 Nazi rise to power as a menace to civilisation, not least to the United Kingdom and the Jewish people, and Balfour had already left the world. But Lloyd George – for all his righteous rage over Britain’s flagging imperial moxie, over honouring international commitments and the wrongs visited upon the Jews – misjudged Hitler from the first.

He had been hounded by regret over the Versailles Treaty’s punitive terms (he blamed the French for that) and viewed the revived Germany as an economic success story and a virile, Protestant bulwark against Bolshevism.

In autumn 1936, six months after Hitler had flouted the Versailles pact by reoccupying the Rhineland, Lloyd George visited Hitler’s Bavaria retreat. A year before, the Nuremburg Laws had stripped German Jews of citizenship and forbade marriage or sex with ‘Aryans’ – earlier laws had barred them from work in government, as teachers, lawyers, doctors or even musicians.

None of these appear to have come up during the visit. Instead they joked, posed for photographs, and lavished each other with praise. On his return Lloyd George insisted Hitler was as ‘the greatest living German,’ even the ‘George Washington of Germany’; he had no militaristic designs – in fact he ‘profoundly admires the British’ – but was merely re-arming out of an abundance of caution and ‘hatred of Bolshevism.’[19] It may be that Lloyd George’s tendency to identify Bolsheviks with Jews – conflating the two was a staple of the Fuehrer’s own rhetoric – allowed him to dismiss Hitler’s anti-Semitism as mere anti-communism.

But re-examining his Peel testimony from the following spring reveals the enormity of his misapprehension. Palestine’s Jewish population had more than doubled in five years – a rise sparked in large part by Hitler’s ascent – to nearly 400,000. Lloyd George said that process ought to continue, seeing strength in numbers: Supposing Jewish Palestine grew by another 200,000, he reckoned, ‘you cannot kill 600,000 people. Even Hitler cannot get rid of the Jews.’[20] The possibility that Hitler would murder ten times that many within a few years was utterly beyond his comprehension.

Finally, as the session came to a close, Lloyd George returned to his earlier contention that Balfour’s promise had kept the Germans tied down, undersupplied and underfed. Here the man’s contradictions – Judeophobe and philo-Semite, militarist and appeaser, Zionist champion and Hitler enthusiast – were on full display. In sentiments uncomfortably evocative of the Nazi Weltanschauung, he reiterated the Jew-as-Bolshevik equation, and added a note of essentialism, of inescapability, to the figure of the Jew himself.

‘I do not say Trotsky was a Zionist, but he was a Jew; Kamenev was a Jew,’ he said. Lev Kamenev, born Rosenfeld, was Trotsky’s brother-in-law and a member of the First Politburo. ‘They were pretty well all Jews, but very powerful in those days and probably non-Zionists. But still a Jew is a Jew.’[21]

References

[1] An uptick in scholarly output since last year has partially filled the relative dearth of material of the preceeding decades. See for example: Sinanoglou, Penny. Partitioning Palestine: British Policymaking at the End of Empire. University of Chicago (2019). Also Dubnov, Arie, and Laura Robson, editors. Partitions: A Transnational History of Twentieth-Century Territorial Separatism. Stanford (2019).

[2] ‘Report of the Palestine Royal Commission,’ Cmd. 5479. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office (1937), x.

[3] The files are in Palestine Royal Commission: Minutes of Evidence Heard at Secret Sessions, FO 492/19, The National Archives. The scholar is Laila Parsons. See Parsons, ‘The Secret Testimony of the Peel Commission,’ Parts I and II. Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 49, no. 1, 2 (autumn 2019, winter 2020), passim. Her account is particularly valuable for revealing the key roles played by two mid-level Palestine officials, Douglas Harris and Lewis Andrews (the latter assassinated by Arab gunmen the same year) in concretising and endorsing a partition plan, one taken up by the report’s primary author, Prof. Reginald Coupland. Parsons was alerted to the secret files’ existence by Steven Wagner, who generously provided them to this author.

[4] The two previous high commissioners who testified were John Chancellor and Herbert Samuel (the latter twice). Weizmann and Ben-Gurion flouted the secrecy instructions, reproducing their secret testimonies in their respective memoirs, likely aided in transcription by the hidden microphone the Zionists had placed in the hearing room chandelier; Winston Churchill also somehow obtained a copy of his testimony for his papers (for these, see Part I).

[5] They had been introduced by C.P. Scott, the long-time editor of the Manchester Guardian, who was keenly interested in the predicament of Europe’s Jews. In his memoir Weizmann called Scott ‘a man who was to have incalculable value to the Zionist movement.’ Weizmann, Chaim. Trial and Error: The Autobiography of Chaim Weizmann. New York: Schocken (1966), 190-200.

[6] Weizmann’s memoir records that among Churchill’s first words were, ‘Well, Dr. Weizmann, we need thirty thousand tons of acetone. Can you make it?’ Weizmann was taken aback but replied that if he could find a way to make a ton, he could multiply that amount by any factor at all. Ibid., 220-222.

[7] In his memoir, Lloyd George claims that in 1917 he introduced Weizmann to Balfour. See Lloyd George, David. Memoirs of the Peace Conference. New Haven: Yale (1939), 722ff (originally published as The Truth About the Peace Treaties. London: Victor Gollancz [1938]). Weizmann’s own memoir (op. cit., 142-145) makes clear he had first discussed Zionism with Balfour over a decade earlier, when the latter was prime minister.

[8] FO 492/19, 516-517, 425-525 (though delivered in secret, these sentiments were included in Peel’s final report and attributed to Lloyd George: see Cmd. 5479, 23-24). Virtually the same text is in Lloyd George’s memoir (op. cit., 724-725), and he had presented similar ideas in Parliament a year before (‘It was one of the darkest periods of the War…it was vital we should have the sympathies of the Jewish community’): HC Deb, 19 June 1936, vol. 313, col. 1340ff.

[9] FO 492/19, 517, 525; similar text is in Lloyd George, op. cit., 725, 737.

[10] Similar sentiment is in Cmd. 5479, 23, and Lloyd George, op. cit., 736-737. In testimony he said limiting immigration for non-economic reasons would be a ‘gross breach… we shall be discredited in the eyes of the world.’ FO 492/19, 517-520.

[11] FO 492/19, 516-518; Lloyd George, op. cit., 723-724, 737. For the Hussein-McMahon agreement, which laid the groundwork for the wartime revolt, see the commission’s report, Cmd. 5479, 16-28, and the 1939 ad-hoc committee on that agreement, Cmd. 5974, passim. Several of the Royal Commission’s Arab witnesses had taken part in that revolt, including Grand Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini and Jerusalem Mayor Hussein al-Khalidi.

[12] FO 492/19, 518, 520. He insisted Palestine had plenty of room for more immigrants: Its current population of 1.25 million was barely a quarter of the figure in Jesus’ time, and that without modern methods of cultivation. The Negev desert, at the time sparsely inhabited by Bedouin, had in Roman times been ‘fully populated.’

[13] Indeed, he said, the heads of all the major Allied states stood behind the Declaration. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, for example, ‘had no particular love for the Jews one way or the other… but his dominant consideration was that it would be very useful.’ FO 492/19, 518, 520, 523. On Wilson in this context, see Cmd. 5479, 24 and Lloyd George, op. cit., 734-737.

[14] FO 492/19, 522, 525. The latter quote also appears in Sylvester, Albert James. Life with Lloyd George: The Diary of A. J. Sylvester, 1931-45. Totowa NJ: Barnes & Noble (1975), 178.

[15] FO 492/19, 519. General comments on the power of American ‘Jewish financial interests’ and the assertion that they slowed Washington’s entry to the war and are in Lloyd George, op. cit., 722, 726. A decade after the delegation to America, Reading became chair of the Palestine Electric Corporation (now Israel Electric Corporation), and Tel Aviv’s iconic power station still bears his name.

[16] FO 492/19, 523 (Lloyd George incorrectly set the figure at ‘tens of thousands’). More than 100,000 Jews are believed to have been killed in those wars, typically targeted by anti-Soviet factions in the Russian Civil War, Polish-Soviet War and Ukrainian-Soviet War, and both sides of the Polish-Ukrainian War. For pogroms in Poland, see Hagen, William. Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland, 1914–1920. Cambridge (2018), passim.

[17] FO 492/19, 524. On Lloyd George, anti-Semitism and the myth of Jewish power, see Segev, Tom. One Palestine Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate. New York: Henry Holt (2001), 36-39. Also Schneer, Jonathan. ‘How Anti-Semitism Helped Create Israel.‘ Foreign Policy, September 8, 2010.

[18] Lloyd George, David. ‘A Scandalous Report.’ Sunday Express, July 18, 1937 (reprinted in various outlets including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch).

[19] Wilkinson, Robert. Lloyd George: Statesman or Scoundrel. London: Bloomsbury (2018), 124-126, 210-211. Low, Valentine. ‘By George, who’s that at a party with Hitler?’ The Times, February 28, 2017. Contemporary accounts include ‘Lloyd George Calls Hitler Among ‘Greatest’ He’s Met,’ JTA, September 23, 1936, and ‘Germany Wants Peace: Lloyd George Impressed by Hitler,’ The Canberra Times, September 22, 1936.

[20] FO 492/19, 522.

[21] FO 492/19, 525. ‘Of course,’ Peel replied. Four of the seven members of the First Politburo were Jews (the two named plus Zinoviev and Sokolnikov), and another – Lenin – was the grandson of a Jew who converted to Christianity as an adult. Kamenev was executed months before Lloyd George’s testimony in Stalin’s purges.

Oren Kessler, in discussing the Peel Commission’s report, writes, “Only one scholar, Laila Parsons, has so far dipped her toe into the more than 500 oversized pages of small, densely written, twin-column text.” In reality she had a predecessor: Arthur Koestler in his 1949 book “Promise and Fulfilment, Palestine 1917-1949” covers much of the same ground.

Per Koestler, “The Zionist leaders, according to Lloyd George’s evidence, promised ‘to do their best to rally Jewish sentiment and support throughout the world to the Allied cause. They kept their word. “

Thanks for reading, David.

Koestler was quoting from a short excerpt of Lloyd George’s secret testimony that was included in the Peel Report itself. As for the full secret sessions, they were still very much declassified at the time of Koestler composing that [remarkable] book. For the particular quote to which you refer, see footnote 8: “though delivered in secret, these sentiments were included in Peel’s final report and attributed to Lloyd George: see Cmd. 5479 [ie the Peel Report], 23-24.”

Correction to my above comment: I meant to say the secret sessions were still very much *classified* (not declassified) when Koestler wrote his book.