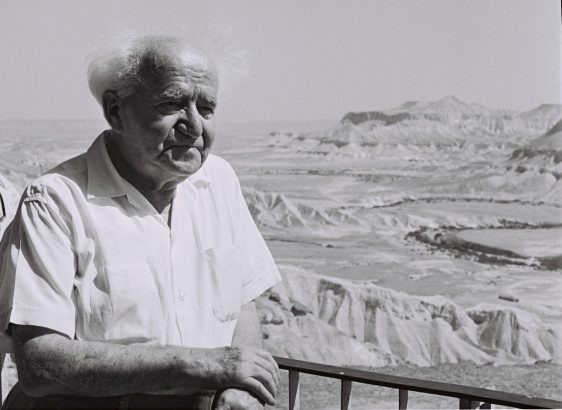

Paul Gross argues that the most fundamental difference between the main parties in the upcoming elections is not to be found on the Right-Left spectrum on national security or economic policy but rather in starkly contrasting visions for the State of Israel: either the liberal democracy envisaged by Zionists from Theodore Herzl, David Ben-Gurion and Ze’ev Jabotinsky embodied in the Declaration of Independence; or the illiberal nationalism represented by the loudest promoters of the Nation-State Law.

Declaration of Independence vs. Nation-State Law

For many Israeli voters, 20 February 2019 was the day which simplified the choice facing them in this election. The day began with the news that, panicked about fragmentation on the Israeli Right, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu succeeded in persuading the now rump Bayit Yehudi (Jewish Home) party to run together with the far-right, racist Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power). It ended with news that, after much speculation, Yair Lapid and Benny Gantz had agreed to run together as the leaders of a joint list – ‘Blue and White’.

Yet these seemingly seismic political developments only served to confirm the already existing fault line broadly dividing Israel’s political parties into two camps – not so much Left vs. Right as ‘Declaration of Independence’ vs. ‘Nation-State Law’.

Weeks before this day of political mergers, Gantz addressed a crowd of Druze protestors, angry at the new Nation-State Law (in the absence of a written constitution, Basic Laws have quasi-constitutional force in the Israeli system). He pledged that, as prime minister, he would look into amending the law, addressing the Druze community’s concern that the law creates a hierarchy of citizenship, with non-Jews rendered second-class. In so doing he promised to strengthen ‘the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic country in light of the Zionist vision expressed in the Declaration of Independence’.

The implications of this statement were unsurprisingly overlooked. Surely an appeal to Israel’s founding document was, as Americans would say, ‘motherhood and apple pie’; universally understood to be ‘a good thing’. Well, no. The reality is that many members of the recently dissolved Knesset would be unwilling to sign up to the Declaration were it resubmitted for approval today. This includes not just the obvious refuseniks, those Arab MKs who would reject its central principle of the right to Jewish national self-determination in the historic Land of Israel, but several members of most parties comprising the outgoing coalition government (probably exempting Kulanu). Their objection would be to sections that allude to Israel’s liberal democratic intentions, in particular: ‘… [the State of Israel] will foster the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; it will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture …’

This isn’t idle speculation but based on the voting and legislative record of coalition members. The Israel Democracy Institute (IDI) has described this outgoing Knesset in historically negative terms, as ‘the most injurious of all with regard to democratic values, freedom of expression, gatekeeping and, above all, minority rights’. A raft of government bills were proposed, some passed into law, some not, attacking the independence of the Supreme Court and freedom of expression, as well as proposals specifically designed to prevent or forestall the consequences of the criminal indictment of Benjamin Netanyahu.

Tourism Minister Yariv Levin, one of the most senior and influential Likud members, has defined a ‘Jewish and democratic state’ as first and foremost a Jewish state, with democracy a purely functional matter pertaining to how the government is chosen. It is what Yohanan Plesner, the President of IDI, has called ‘majoritarian’ or ‘hollow’ democracy, as opposed to the ‘substantive’ democracy, which Israel has enjoyed, more-or-less, since its establishment, with equality before the law, a separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and the rule of law. Such a majoritarian democratic outlook inevitably deals in the currency of populism, with the majority looking to retain power through feeding the fears and prejudices of its electoral base, demonising other sectors of society and attacking the legitimacy of institutions that are a check on the government’s power. (As Yair Lapid pithily put it, checks and balances are required to ensure that 61 Knesset members cannot simply vote away the civil rights of the other 59.)

The relevance of the Nation-State Law lies in the explicit rejection of the Declaration of Independence by the coalition members who most forcefully promoted it. (For example, Levin and Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked, who exemplified the law’s majoritarian spirit by proclaiming pre-eminence of ‘Jewish’ over ‘democratic’ in a rebuke to the Supreme Court, said: ‘Zionism will not continue to bend its neck to a system of individual rights.’) The absence of any language invoking the ‘equality’ wording of the Declaration is stark, especially when one considers that an alternative draft was proposed, explicitly incorporating the language of the Declaration, (not by a member of the opposition, but by the Likud’s own Benny Begin) and subsequently rejected. That version has since been adopted as the preferred draft of the Yesh Atid party, which forms one part of the new Blue and White party.

Ultimately, the gravity of this moment in Israel’s legislative history is not – as some more hysterical critics have alleged – that the Nation-State Law moves the country overnight from democracy to ethnocracy. The actual legal provisions of the law are not so far-reaching. Its real significance is the political trajectory it sets for Israel. This law was intended to be the preamble of Israel’s future constitution, the opening declarative statement of what the State of Israel is. Many of the supporters of the Nation-State Law, and certainly its drafters – principal figures in the Likud and what is now the New Right party – intend for it to be the most authoritative self-definition of the State of Israel, displacing the Declaration of Independence, which informally had that role up to now. These MKs have a different conception of what democracy means in a Jewish state, than those who voted against. Theirs is a reimagining of ‘Jewish and democratic,’ quite at odds with the expressed intentions of Israel’s founders, who all – whether socialist or liberal, secular or religious – signed the Declaration of Independence.

Not simply Left vs. Right

The division between two conceptions of democracy, and two different definitions of ‘Jewish and democratic’ could be more easily rendered as ‘Left and Right’. But it is a simplification that should be resisted. It is true that the parties that clearly identify with the Declaration of Independence are mainly on the Left and Centre (Meretz, Labor, Blue and White). But what to make of Moshe Yaalon’s Telem faction, running as the junior partner with Gantz in Blue and White? A former hawkish Likud Defence Minister, Yaalon and others on his list are very much part of the Israeli Right. As of course is Benny Begin of the Likud, who abstained in the final vote. Both Begin and Yaalon oppose the establishment of a Palestinian state – the definitive right-wing position in Israel. But both share the Declaration of Independence conception of what Israel should be: a Jewish state with equal rights for its non-Jewish citizens

Begin is part of a dying breed in the Likud, a liberal nationalist in the mold of his father Menachem, the first Likud prime minister, and it is no surprise that he has decided against running this time around. An earlier liberal refugee from the Likud, Dan Meridor, observed: ‘Likud was a unique mix of two great ideas. The liberal idea of the rule of law, human rights, of the importance of the individual; and the national story of the Jews. This delicate balance was led by Menachem Begin when he headed Likud … this balance has been disturbed in favour of more nationalistic, national-religious ideas.’

Despite the claims from Netanyahu and others that to oppose the Nation-State Law is to be ‘a leftist,’ some of the most trenchant criticism came from Begin-ite right-wingers, such as President Reuven Rivlin, and former ministers Meridor and the late Moshe Arens.

Yaalon associated himself with this group when he resigned as defence minister and quit the party: ‘… the majority here is sane and seeks a Jewish, democratic and liberal state … but to my great regret, extremist and dangerous forces have taken over Israel and the Likud movement and are destabilising our home and threatening to harm its inhabitants … this is not the Likud I joined – the Likud of Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Menachem Begin.’

The reference to Jabotinsky is instructive. The founder of Revisionist Zionism – ostensibly ‘right-wing Zionism’ – was actually a profoundly liberal, and quite brilliant political thinker. He believed that the Jews would have to fight long and hard against the Arabs to win independence and to continue to defend their new state, but he was also committed to completely equal rights for Arab citizens of that state. More specifically, Jabotinsky spoke forcefully against the tyranny of the majority, insisting on strong civil institutions to protect minority rights. He even pre-empted the Nation-State Law debate, declaring his belief that state constitutions should not ‘include special paragraphs explicitly guaranteeing its “national” character … the best and most natural way is for the “national” character of the state to be guaranteed by the fact of its having a certain majority’.

‘Illiberal democrats’

So if not ‘Left vs. Right,’ what terminology would be most applicable for this democratic divide? ‘Liberal’ vs. ‘illiberal’ perhaps. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban coined the phrase ‘illiberal democracy’ to describe his ideology and there are certain similarities between the legislative proposals of Israel’s ‘Nation-State’ parties, and those of populist governments in Europe such as Hungary and Poland. Culture Minister Miri Regev’s attempt to impose a ‘loyalty’ criteria on arts and culture projects that receive state funding for example, or Shaked’s proposed ‘supersession law,’ which would allow a simple majority of the Knesset to overturn a Supreme Court decision. (The degree to which Shaked sees the Court as a threat to her vision of ‘democracy’ is apparent in the extraordinary parallel implied by a prominent election slogan of her New Right party: “[Naftali] Bennett will defeat Hamas; Shaked will defeat the Supreme Court”.) Both Regev’s and Shaked’s efforts seem to echo the intent – if not the extent – of authoritarian moves in Budapest and Warsaw.

It is worth noting, however, that neither of these bills became law. And here some restraint is called for in comparing Israel to countries where liberal democracy has basically fallen apart. Though Israel is not the US, with its written constitution and multi-layered system of checks and balances, neither is it a relatively recent democracy like Hungary, Poland or Brazil. Israel was established as a liberal democracy and has remarkably retained that status throughout its nearly 71 tumultuous years. It has a hyper-active and influential media that, with relatively few exceptions such as the slavishly pro-Netanyahu newspaper Israel Hayom, freely and routinely criticise the government. The Supreme Court remains a powerful check on majoritarian impulses; while senior civil servants like the Attorney General and the Civil Service Commissioner can and do act against executive power when it is deemed to have crossed legal or ethical lines.

The much-maligned Israeli electoral system also mitigates against one, all-powerful populist party taking charge. Israeli coalitions always feature multiple parties, and it is extremely unlikely that a prime minister would be able to reach the magic number of 61 Knesset seats – a governing majority – exclusively with avowedly illiberal parties. The outgoing government, frequently referred to as ‘the most right-wing in Israel’s history,’ nevertheless contained one party with more moderate sensibilities. Kulanu entered the coalition having obtained from Netanyahu a guarantee that they could vote against government legislation which threatened the Supreme Court and the rule of law. (It is not incidental that in this election, Kulanu is running as ‘the sane right,’ with none other than Menachem Begin featuring on campaign posters alongside party leader Moshe Kahlon.)

No, Israel is not an ‘illiberal democracy’. Not all 62 of the MKs who voted in favor of the Nation-State Law did so out of a wish to move the country away from its liberal democratic moorings. Many were simply following party discipline. Nevertheless, within the parties which make up today’s Israeli Right other than Kulanu (Likud, the New Right, United Right and Yisrael Beiteinu) there are a number of prominent illiberal democrats, and right now they seem to be in the ascendancy. Netanyahu himself was historically not part of this group, but his all-consuming desperation to cling to power has led him to become arguably the most illiberal of them all. He is calling the shots in a Likud election campaign that has smeared the Attorney General, the police, the media and most political opponents as ‘leftists,’ and ‘unpatriotic,’ promoting wild conspiracy theories straight out of the authoritarian populist playbook.

The choice ahead

This coming election will likely see a return to the days of two big parties gaining over half the Knesset seats between them. Unless Netanyahu is persuaded to step down as leader of his party (for example, after unexpectedly poor election results) the next government of the State of Israel will be led by either the Blue and White of Gantz and Lapid, or the Likud of Netanyahu. The most fundamental difference between the two does not lie in specific domestic or foreign policies, but in their vision for the State of Israel: either the liberal democracy envisaged by Zionists from Herzl, to Ben-Gurion to Jabotinsky, and promised in the Declaration of Independence; or the illiberal nationalism represented by the loudest promoters of the Nation-State Law. The stakes are high indeed.

I wonder how the author would respond to the proposition that the Right of Return that enables any Jew from any nationality the rights to Israeli citizenship solely by virtue of his identity and denies that to any other group including Arabs is not “equal”under the laws? How would the courts respond?What would he do about it?

Not so long ago, a liberal Democratic Senator from Illinois named Barack Obama won the presidency on a platform that included an anti-gay marriage plank. Today, a man can get fired from his job for complaining about men entering girls’ bathrooms.

Jabotinsky did not envision a future where a minority of cultural elites would have the power to alter the fundamental ordering principles of society. Do not be surprised when the people decide they have to embrace any means necessary to forestall that.