Noga Emanuel reviews comedy-drama Shababnikim (The New Black) that follows the lives, loves, misadventures, and tribulations of four recalcitrant yeshiva students, each struggling against the strictures of the ultra-Orthodox world they inhabit. She argues that the show ‘succeeds because it refuses to console, flatter, or blame. It suggests tradition examine itself, secularism temper its smugness, and that power submit to scrutiny. The work doubts loudly, believes cautiously, and trusts neither slogans nor sanctimony.’

“Two nations; between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets; who are formed by a different breeding, are fed by a different food, are ordered by different manners, and are not governed by the same laws…”

~ Benjamin Disraeli

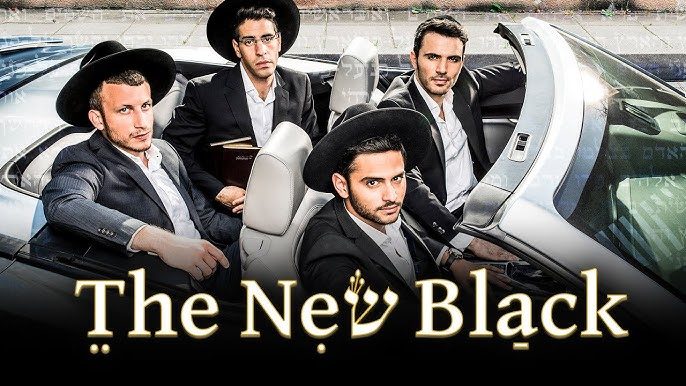

The Israeli television series Shababnikim is a comedy-drama that premiered in Israel in 2017 and has since run for three seasons. It follows the lives, loves, misadventures, and tribulations of four recalcitrant yeshiva students, each struggling against the strictures of the ultra-Orthodox world they inhabit. In January 2021, the first season began streaming on Netflix with English subtitles, under the title The New Black, thereby introducing this ostensibly insular story to a global audience.

The series casts a sharp and inquisitive lens on the cultural mores within ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) community in Israeli society, and the constant chafing along the uneasy, unresolved, and increasingly volatile interface between secular and religious dispositions in Israel.

Through its engaging mixture of humour, drama, and ironic observation, Shababnikim becomes more than a mere situation comedy. It belongs rather to the venerable literary tradition of the comedy of manners, recalling the work of Jane Austen or Oscar Wilde. A comedy of manners is not a trivial genre. It gently but incisively ironises the behaviour, customs, social norms, and values of a particular class, exposing the futility and superficiality of pretensions, keeping up appearances, and the inadequacy of public opinion and social or ethnic classification when confronted with serious questions of life choices, hope, friendship, love and civic sense of duty.

The dramedy under consideration here attempts – and succeeds – in revealing the tensions and irreducibly human complexities of a visibly recognisable, socially reclusive, and much misunderstood segment of Israeli society.

The series does not aspire to reproduce the average, quotidian existence of yeshiva students. If you seek such realism you can take a walk in one of the ultra-religious neighbourhoods in Jerusalem. There, nothing theatrical occurs: no chandeliers crash from ceilings, no one gets into fracases with football players in a Jerusalem park, no yeshiva student secretly listens to Heavy Metal music, the rich philanthropist’s daughter does not wander around the yeshiva, and when a yeshiva student accidentally wanders into an actual minefield, he does exactly what the soldier says and does not enter into an ideological debate among the unexploded mines.

But art that confines itself to the mundane, the ‘universally known’, and the presumably familiar landscape is a mere record, a documentation and confirmation of the obvious. The value of a work of fiction – be it a film, a TV series, a play, or book – resides in its departing from the banality of realism. Art, good art, unveils the different story, draws up from beneath what is not immediately apparent, to the surface, to the sunlight.

The great literary critic Harold Bloom argued that what gives fiction its lasting value is its strangeness. Not the strangeness of eccentricity or oddity, but the kind that jolts the imagination into encountering the unfamiliar aspects and depths of the other. Fiction contests banality, categorisation and reduction of individuals to sociological specimens, easy historicism or identity-based and flattening interpretations. The secret of Shababnikim’s outstanding quality and popular success is in achieving exactly this ‘estranging’ effect.

Two solitudes: The reciprocal gaze between secular and Haredi camps in Israeli society

At the centre of Shababnikim are young yeshiva students who, uneasily ensconced within the cocoon of Haredi lore wonder about the so-called liberties they glimpse just over the fence. The series understands that the real drama is not in the temptation, but the cost of either succumbing or resistance to it, and the realisation that escape is not necessarily liberation by default.

Shababnikim follows the four students at an elite yeshiva. Three of them, Avinoam (Daniel Gad), Leizer (Omer Perlman), and Meir (Israel Atias) are slackers who keep up the appearances despite everything. The fourth, who reluctantly joins the posse, Gedalia (Uri Leizerovich), is a serious and ambitious wannabe scholar, socially awkward, striving with all his might to stay on the straight and narrow path of Torah.

One of the refreshing aspects of the series is the absence of sneering in its portrayal of the ultra-Orthodox world. The authors dramatise the subtleties of yeshiva students’ lives and the internal tensions within Haredi society. The term shababnik itself is borrowed from Haredi slang, an uncharitable reference to aimless Haredi youth who swerves from the accepted norms of Haredi culture. It gained notoriety among the general Israeli public thanks to the series. The series made the Haredi world less opaque to secular audiences, and offered them the opportunity to witness the challenges facing mainly its younger generation.

The plot does not merely peer into it but actively meddles in it. Created by Eliran Malka, the series probes a community that subsists on self-imposed seclusion and maintenance of hierarchy, yet is increasingly forced to handle problems that arise from the constant and inescapable contact with the secular world that adjoins its boundary. Shababnikim refuses to flatter the constrictions of tradition, or pontificate about the great liberties of the secular system. Both herds are wryly dissected, as they gaze on and step on each other’s toes. To paraphrase Nietzsche, if you gaze for long into an ethos, the ethos gazes back into you …

The story’s underlying premise is: let’s see what happens when a modern young Yeshiva student goes to yoga class, hangs out with friends drinking beer at some popular city Plaza, travels around the country, and asks himself: Can I blend in without losing my piety and faith? One Israeli critic described the modern Haredi featured in the series as a double agent – living in two worlds. Sometimes he seemingly belongs to neither, or perhaps he precisely represents the chance to bridge between them. The problem with this label is contained within its implication. Can the agent who performs for two opposing sides be a bridge between both sides?

The Comedy of Manners: Irony and Critique

Life in Haredi circles is governed by unwritten rules of status, pedigree, money, and ‘proper’ behaviour. The irony arises from the gap between the moral language and the etiquette the characters use, such as respect for rabbinical authority, tradition, good manners and mutual caring, and the thoroughly transactional logic that actually structures their world. Marriage is not merely romantic or religious, but the central economic and social mechanism through which class and ethnic boundaries are preserved, negotiated, or occasionally subverted. Shababnikim reveals how even a community that claims spiritual and righteous equality reproduces inequality with exquisite precision.

The four young students in a Jerusalem Yeshiva form a circle of friends standing apart from the rest of the Yeshiva. They are all roommates and each is defined as individual but also illustrates a certain type within Haredi Israeli society.

Avinoam Lasri belongs to the upper echelon of the ultra-Orthodox world. As the son of a Member of Knesset, he carries recognised family status and enjoys access, protection, and influence within the system. Avinoam is good-looking, confident, socially intelligent, and verbally articulate. His leadership within the group is informal, based on charisma and strategic awareness. At the same time, he experiences the tension between the expectations his family’s inherited status places upon him and personal self-definition and independent identity. Within the narrative, it is mostly Avinoam who initiates movement between the separate social spaces, and maintains a balance between conformity and deviation. His interactions with characters outside the yeshiva, particularly Shira, an art student in Bezalel Art Academy, expands the narrative beyond the institutional setting.

Dov Eliezer “Leizer” Brown comes from a wealthy family based mainly in New York. His financial security places him at a distance from the immediate pressures faced by the other students. Leizer is stylish, ironic, and reserved. He avoids deep commitment while maintaining social authority through charm and material resources. There’s one episode where the four friends take a road trip to the Golan Heights, and Leizer, unaware, walks into a minefield and needs to be rescued by IDF soldiers. He refuses to be carried on the soldier’s back to be rescued, if the price of rescue is surrendering his personal agency. This scene gives the viewers a rare opportunity to understand something about into Leizer’s personality. He is something of a modern anti-hero, with unplundered depths. If any of the four friends were to enlist for military service, he would be the most likely.

Meir Sabag comes from a humble Mizrahi religious family. He lacks both financial backing and social privilege. Intense, reactive, insecure, and expressive, he seeks validation through integration within the unforgiving yeshiva hierarchy. Meir is the character through whom the inter-ethnic conflict becomes explicit and crude. In the ultra-orthodox world, his Mizrahi descent is a real obstacle that demands real sacrifices from him to circumvent. Meir is sweet, beautiful, a loyal friend, and faithful son to his widowed father but lacks the necessary character tools to deal with the almost mind-boggling humiliations that are visited upon him. As a Moroccan Haredi, he has no real assets to offer a matchmaker to arrange a ‘good’ match with an Ashkenazi bride from a wealthy home. Her parents refuse the match point blank. But that’s just the beginning of this shabby cringeworthy story. Meir is ultimately left high and dry because of his ethnic background. The viewers watch him and the family who humiliate him with dropped jaws. How is it possible, in this day and age? And why does he tolerate it?

The sheer vulgarity of the intra-ethnic sensibility within the Haredi community is deliberately done, or overdone, by the creators of the series. The Mizrahi-Ashkenazi hierarchy as portrayed via Meir’s story is also a mirror for lurking undercurrents in the secular society. A fogged mirror to be sure, since in modern Israel such openly practiced rituals of humiliations as Meir is subjected to are much frowned upon by progressive intellectuals. The staging of the Haredi obsession with ethnic suitability may be read as an ironic reminder to secular fundamentalists that similar demons still linger within their own worldview, concealed beneath torrents of grandstanding and sanctimonious rhetoric, but wounding no less. (Spoiler alert: Meir is ultimately rescued from utter pusillanimity but by the tough love of a woman who is his complete opposite.)

Gedalia, the Johnny-come-lately in the quartet, is defined primarily by his role as a model yeshiva student, destined and eager for a brilliant rabbinical career. He is disciplined, serious, and hard-working, conformist to a fault – the sort who would qualify for the Haredi Forbes list of ‘30 under 30 to watch’. Gedalia believes in structure and clarity, and initially views deviation as moral failure rather than complexity. Yet Gedalia is itchy in his skin, and under his steadfast convictions there are bubbling emotions, edginess, easily aroused irritation with his own unworldliness, sensual vulnerabilities and relentless shock at the enigmas of the universe. Through his gradual evolution among his happy-go-lucky friends, his stormy on again/off again relationship with Dvora, and some sage advice from his rabbis, he loses his uncouth piety and slowly shifts from certitude to critical observation.

Played by Maya Wertheimer, Leizer’s twin sister, Dvora, is a strong female presence in the series, independent, resolutely determined to insert modernity and equality into her sphere of life in the Haredi community. The viewers are little prepared for her appearance or the quality of the energy she brings into the milieu. Just as we thought we more or less understood the series, there she was, a disruptive, turbulent, brawling, quarrelsome red-haired virago.

The twins promised their New-York based parents that they would meet at least once a month. Gedalia is accompanying his friend, present accidentally – he has neither sought this meeting nor was he expected. At first he regards Dvora with distant politeness and when his attention falls upon a set of books lying on the table, he assumes they are intended for her brother. The notion presents itself as indisputable, requiring neither confirmation nor doubt. ‘Nice of you to bring them’, he salutes her.

Her correction is calm. The books, she states, are her own.

At this, a momentary stillness intervenes. Gedalia looks again, as though sight itself might correct what reason resists. His response follows, unguarded and assured, shaped by his conviction rather than reflection. A woman, he implies, does not occupy herself with such study.

Dvora neither flinches nor retreats into a huffy silence. Instead, her bearing alters with a firm inward resolve. What began as an incidental exchange assumes the gravity of a debate. She challenges not merely his statement, but the belief from which it springs. When his dismissive replies finally sting her, she turns to her amused brother and asks pointedly whether ‘all your friends like this creature?’. Gedalia adds fuel to the fire by shrugging his shoulders, ‘How typical of a woman! The first sign of opposition and she turns to emotions!’

Dvora will not let him off the hook. With clarity and force, she cites revered rabbinical sources with precision and confidence in support of her position that women can and should be able and allowed to study Torah, Jewish law.

Gedalia finds himself unprepared and tries to parry her arguments by quoting insulting opinions about allowing women to study. The assumptions he relies on are no help at all. Before him stands not a defiant outsider, a bra-burning feminist, but a woman fully informed from within his own world, whose intellect and faith expose the narrowness and insufficiency of his worldview. The meeting ends in tatters when Dvora’s patience is overtaxed and she flounces out in rage.

And this is the beginning of the delightful romance between the two, a courtship right out of a Jane Austen novel.

Shlomi Zacks, the giddy and indefatigable matchmaker and ebullient straight shooter matchmaker rendered with considerable discernment and much verve by Guri Alfi, operates primarily as structural force rather than a fully developed individual. He works to enforce boundaries and maintain order, preparing the young hopefuls for life in general and in the Haredi universe more particularly. Shlomi’s character is merely a spice in the first season but his animated presence proved so irresistible that the producers justifiably apportioned him a bigger role and importance.

Shlomi is not to be dismissed as a figure of mere amusement. He is a professional in mediation and adjustment, possessed of an intimate knowledge of the system within which he labours, and its rules of engagement. His occupation does not incline him toward encouraging romantic fancy, but rather obliges him to the prudent administration of risk in a society where a match is understood as a social contract, involving families, lineages, finances, institutions, and reputations, all vigilantly observed by the members of the community, of either gender or age.

Mr. Zacks is mindful of the uneasy position in which the young people under his counsel are placed, suspended between individual longings and considerations of parental and communal expectation, and the ever-present anxiety of social ostracism if and when they put a foot wrong. The advice he offers is not rooted in cynicism, but experience.

The language in which Mr. Zacks habitually expresses himself when lecturing his matrimonial candidates is more suited to a merchandising company than romantic pairing. His use of phrases like ‘matters to be passed,’ ‘secured,’ or ‘brought to conclusion’ may strike the listener as unfeeling yet it is precisely through this mode of expression that he succeeds in his endeavours. He subscribes to – or perhaps of necessity abides by – the belief that affection is seldom the beginning of a successful union, but more its consequence. The perfect, he would say, is enemy of the good, and his job is to promote the good …

It is here that Mr. Zacks distinguishes himself most clearly and is indispensable to understanding the world in which our four protagonists drift. He does not assert that the philosophy of his matchmaking business is admirable, or even particularly just, but rather that it functions. He is not peddling happiness, but rather security, safety, perseverance, future generations. His character inspires both affection and disquiet. At once diverting, humane, clear-sighted, and reflecting a social truth that is not easily borne, Mr. Zacks is not a product of the world he serves, but rather its interpreter.

We also see not just the world of the young men, but the world of the rabbis in the yeshiva, their internal jousting for power and influence. For example, the liberal minded and likable Rabbi Bloch who tries to help his giddy and often reckless students navigate the way in the world and their own life versus the martinet Rabbi Spitzer who imposes an almost monastic discipline on the students.

The marriage of mutual inconvenience

When it premiered in 2017, Shababnikim was a series of and for its time. Haredi power had become undeniably structural, not marginal, while secular Israelis increasingly experienced religion as coercion and encroachment rather than tradition. Meanwhile, many Haredim felt besieged by a type of modernity they did not invite, do not control, and which comes with real demands from the modern state. The show suggested that the real danger lies not in the gap between belief or disbelief, but in mutual ignorance hardened into differently constructed Jewish identities.

Almost four years passed between the second and third seasons. The second season left the show’s protagonists as they make their way to the Western Wall, after being forced out of their Yeshiva in Rehavia, Jerusalem. They had tried to set up proximity, camaraderie and exchange with secular Jews, and found themselves becoming custodians of the very institution they once scoffed. They find that recalcitrance is fun and exhilarating until it bumps on responsibility. They suffer from the ‘growing pains,’ and the realisation that tearing down hierarchies does not exempt one from building replacements.

So the hopeful gesture of a ‘hybrid’ yeshiva open to difference ends in a whimper. The series knows that Israel’s crisis between religion and state is not an engineering problem awaiting solution, but a human question demanding deep and exacting reckoning.

Seasons 1 and 2 maintain a certain levity, an optimism that with a little bit of good will and creative concoctions, Israelis can device a modus operandi that will work out for the two solitudes. But by the time the third season is rolled out in March 2025, in the real Israel, the conflict between the ultra-religious and the secularists had reached near boiling point. Secular Israelis can no longer accommodate with equanimity the Haredi community’s reliance on the state without sharing in the terrible costs of maintaining it.

October 7

Most of the third season was filmed before October 7, 2023. It was supposed to end in its tenth episode, with the older, mellower, more mature Shababniks coming to terms with their limitations and curtailed dreams of glory. It would not have been a shabby end at all.

One of the most memorable moments from the first season is the ‘minefield episode’, in which Gedalia furnishes a ‘knockout question’ in the ongoing debate over Haredi military draft. “I’ll ask you a simple question… If the entire army were Haredi, and you had to send your son, would you send him without fearing that he’d come back religious?”

A lot has happened since that episode. How might it be possible to tell the bleeding life we are living within a comedic series about Haredi yeshiva students?

The series’ most unsettling finale episode was written in the shadow of October 7, abandoning metaphor and illusions altogether. Three weeks after the cursed day, the group undertakes to go on mission to retrieve a set of tefillin from a home in a devastated kibbutz in the Gaza Envelope.

In the stunned atmosphere of post October 7 Israeli society, the episode crumples the distance between the Haredi enclave and the national catastrophe. The question that hovers over it is neither theological nor political but existential: in a state of war, what does belonging mean for a community that has trained itself to stand apart from the collective?

The series does not answer and one film critic suggests that the question itself is an indictment. Personally, I don’t know. Perhaps we need to resist the pressure to rush and explain things in the traditional or conventional way, to prescribe solutions that Israelis would have liked to see and hear. Instead, perhaps Israelis need hope, defined by Jonathan Lear in his book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, as directed toward a future good that transcends current understanding, requiring imaginative flexibility.

Epilogue:

I think that the comedic drama created by Eliran Malka and the late Dani Parren is nothing short of a masterpiece.

I like that Dvora quotes Maimonides who applied Aristotle’s ‘golden mean’ to Jewish ethics (Mussar), and mildness of temper as a middle path between excessive anger and indifference.

I like Shlomi the matchmaker’s advice about the prudence of occasionally leaving things unsaid.

I like that the producers and writers provided a Dickensian gallery of characters marked by eccentricity, greed, stupidity, generosity, humility, piety, etc. without beclowning anyone and without stripping them of all value or integrity.

Shababnikim succeeds because it refuses to console, flatter, or blame. It suggests tradition examine itself, secularism temper its smugness, and that power submit to scrutiny. The work doubts loudly, believes cautiously, and trusts neither slogans nor sanctimony. One of the central struggles within the Haredi public concerns the question of how much it should intermingle with the secular world outside while the secularist public questions how far it should go (if at all), in accommodating Haredi insularity and necessities. Both struggles are held up for scrutiny and reproach. The series’ three seasons offer a parade of experiences, situations, shenanigans, debates, confrontations, that both exemplify the follies and foibles of each side and the potential for a better, more functional, less riotous society.