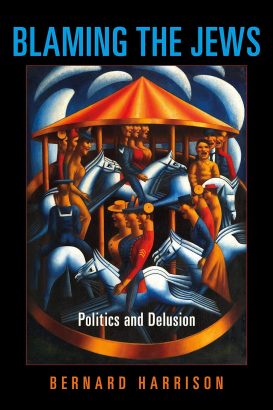

Bernard Harrison’s book Blaming the Jews: Politics and Delusion (Indiana University Press, 2020) is, we believe, a vital text. Questioning the assumption that antisemitism affects or targets only Jews, it demonstrates that when allowed to go unchecked, antisemitism is potentially damaging to us all. Fathom editors asked the author to summarise its 488 pages, especially his conception of what is unique to antisemitism, which is not racism but ‘political antisemitism’ – i.e. ‘a strange body of pseudo-explanatory theory concerning the supposed quasi-demonic power, not of this or that Jewish individual, but of the Jewish community as a supposedly tightly organised collective, to influence and control world events’. He also explores the practical pay-off of political antisemitism, ‘eliminative antisemitism’. ‘Blaming the Jews’ he writes, ‘is an extended study of the nature, and the functions in non-Jewish political life, of this extraordinary pseudo-explanatory theory.’ The editors hope Harrison’s book can gain a wider audience

In 2020 Indiana University Press published my Blaming the Jews: Politics and Delusion. The argument of the book takes off from a puzzle. Why do so many writers on the topic at present find it so difficult to arrive at a unitary definition of the notion of antisemitism that a number of them conclude it to be in principle indefinable? My opening move is the irritatingly obvious one of pointing out that before despairing of the possibility of finding a unitary definition of a given phenomenon, it is as well to make sure that the phenomenon in question is a unitary phenomenon.

What is ‘political antisemitism’?

The book argues that in the case of antisemitism, it is nothing of the sort. We use the term ‘antisemitism’ basically to designate prejudice, that is to say, factually groundless hostility, towards Jews. But groundless hostility to Jews can manifest itself in two quite distinct types of phenomena, only one of which is unique to Jews. The first – social antisemitism – is ordinary ethnic prejudice, of a kind from which many other ethnic or immigrant groups suffer or have suffered in the past, applied in this case to Jews. Ethnic prejudice is an attitude of mind, of hostility and contempt, evoked by any member of a despised group, merely on the grounds that that person is a member of that group. The second – political antisemitism – is not an attitude of mind at all, but a strange body of pseudo-explanatory theory concerning the supposed quasi-demonic power, not of this or that Jewish individual, but of the Jewish community as a supposedly tightly organised collective, to influence and control world events. Antisemitism in this second sense is unique to the Jews, simply because the Jews are the only people perennially singled out by it as possessing the extraordinary powers it ascribes to them.

Statements of political antisemitism can be found in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, in Mein Kampf, in the Charter of Hamas, in the speeches of Iranian leaders such as Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and widely elsewhere. Its main claims are that ‘the Jews,’ considered as a collectivity, are not only a people united in the service of evil, but a people gifted with vast and quasi-demonic powers of conspiratorial organisation and financial manipulation that enable its members to widely infiltrate non-Jewish institutions and secretly divert their powers to the service of nefarious Jewish goals intrinsically hostile to non-Jewish interests. The presence of Jews in non-Jewish societies thus presents a serious threat to the latter. Because of the supposedly vast and secret nature of the powers exercised by the Jews this threat cannot be addressed by negotiation, but only by eliminating Jewish influence altogether, by forced conversion, mass expulsion or by more radical means. This basic system of beliefs has displayed astonishing consistency in Europe since late Classical times. On the other hand, the specific evils blamed on ‘the Jews’ by adherents of the system have varied arbitrarily from century to century, ranging from the abduction and murder of non-Jewish children in order to mix their blood with the Passover matzo (the ‘Blood Libel’) to conspiring to deny victory to Germany in the First World War. Blaming the Jews is an extended study of the nature, and the functions in non-Jewish political life, of this extraordinary pseudo-explanatory theory.

The ‘dreamlike distance from truth’ of Political Antisemitism

If its claims had any basis in reality of course, then, given the basic definition of prejudice as factually groundless hostility, the theory would not be a version of antisemitism. It would be the timely wake-up call that its deluded believers imagine it to be. But in fact its claims are vacuous. Not only do they have no basis whatsoever in reality, they are not claims of a kind that conceivably could have a basis in reality. One might object on empirical grounds , for instance, that the Jewish community lacks the kind of ironclad unity in pursuit of common goals ascribed to it by the theory; that in fact there are few more argumentative and divisively opinionated communities on the face of the planet: ‘Two Jews, three opinions.’ That would be argument enough to refute that plank of the antisemite’s theory, but would fail to capture the full gravity of the difficulty facing him, which is that no community is, or possibly could be, as united behind common goals as he imagines the Jewish community to be. Other main claims of the system share the same dreamlike distance not merely from truth but from the very possibility of truth. No actual conspiracy could possibly be as vast, as successful and as undetectable as the World Jewish Conspiracy, no financial abilities as flawlessly insusceptible of bad calls or fatal mistiming as those of the imagined Jewish Financier. Nor do we even need to point to these deficiencies in order to establish that world affairs are not under the control of the Jews. World affairs are not under the control of the Jews, because they neither are nor could be ‘under the control’ of any single human agency. What rules human affairs is a vast array of competing interests and powers, the overwhelmng bulk of them with no connection whatsoever to the Jews. In the same way, Blaming the Jews argues, many of the specific charges laid over the centuries by political antisemites against ‘the Jews’ lack not only truth but even the possibility of proving true. The Blood Libel, for instance, is false not only because Judaism offers o religious reason for abducting children, but because the specific reason envisaged by the Libel, involving the mixing of non-Jewish blood into the Passover matzo, is specifically excluded by Halacha (Jewish religious law), which forbids observant Jews to consume blood, even in the minute amounts sometimes found in an egg. One might as well accuse Hindus of stealing cows in order to enable their priests to perform some supposed Hindu rite involving a meal of roast beef.

Political antisemitism is a disease of radically redemptive politics

The book now turns to consider a further puzzle, this time one raised by the distance not merely from truth, but from the in-principle possibility of truth, at which political antisemitism operates. Why should anyone have ever thought such a farrago worth inventing and propagating, Cui bono? Who profits? And what kind of profit is involved? Political antisemitism is plainly not a Jewish but a non-Jewish invention. So it is to non-Jewish social and political life that we must look for an explanation of its utility. Clearly, now, the myth of secret Jewish control over non-Jewish affairs can in no way advance the real practical ability of non-Jews to understand or control their world. Yet in some way it must seem, sometimes, to some groups, to offer advantages of that kind. What kind of advantages, precisely?

The book resolves this question into two subordinate ones. First, what interests, and whose, are served by a myth of secret alien control? Second, why should the central role in the enduring version of this myth present in European culture over the past two millennia have been assigned to the Jews?

To the first of these questions the book offers the following answer. A main characteristic of European culture has been the successive rise to prominence of vast projects aiming at the systematic redemption or renovation of society. Such projects include Roman citizenship, Christianity, the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, Marxism, Socialism and Fascism. Any such project must represent itself as both deserving and capable of obtaining the unreserved allegiance of the entire human population – the nation, Europe, or humanity at large – whose culture and institutions it considers itself called upon to renovate. A major problem confronting any such project is that both claims invariably have their limits. Inevitably there will come a point at which the underlying assumptions of the project prove faulty and disaster of some sort ensues. At the same time there will always be elements of the project’s target population who altogether reject the project and endlessly chip away at its popularity with others. There is bound, therefore, to be at certain moments advantage to be gained from persuading people that this or that disaster is not the fault of the project, but of an organised alien group, real if possible, imaginary if necessary, which does not have the interests of the people at heart; and that opposition to the ideas of the project is issuing solely from a few simple souls misled by that same organised alien group, whose object is to further their own sinister goals by disrupting, as far as they can, the justified homogeneity of belief and ideals among ‘our own people’ necessary to the success of the project. Political antisemitism, in short, is a disease of radically redemptive politics, which is why it can move with ease from right to left and back again on the spectrum of such movements.

Why the Jews?

There remains the second question: why the Jews? The answer the book offers is that what has fitted the Jews for the role assigned to them in the fantasies of political antisemites is, sadly enough, the success of the Jewish people in maintaining a coherent culture and sense of national identity over millennia of diaspora and savage if intermittent persecution. What makes Jews both hateful and profoundly disturbing to those leading radically redemptive political or religious movements in the non-Jewish world, the book argues, is the persistent refusal of a majority of Jews to abandon their Jewishness and join, wholeheartedly and with no reservations, whatever redemptive movement happens to be leading the van in the non-Jewish world at the moment: to cease to be Jews, in other words, and to ‘join us.’ This refusal, the book argues, has its roots in the nature of Judaism. What makes the obdurate refusal of a permanent core of Jews to exchange completely and without reservation their Jewishness for whatever happens currently to be on offer to them from the redemptive politics of the non-Jewish world, so irritating and disturbing to supporters of any politics of that type, is the suspicion that it is rooted in a belief among Jews – that observant Jews can in any case hardly disguise from many of the non-Jews with whom they interact – that Judaism offers them not only something more satisfying, but something more morally compelling. The book’s arguments for this conclusion include reference to the long history of attempts to establish that the fidelity of Jews to Judaism is in itself sufficient grounds for convicting Jews of lacking reason, true religion, and possibly even humanity. These attempts include the Christian dismissal of Judaism as an archaic and superseded religion, a religion of law rather than love; Kant’s account of Judaism as incompatible with adult moral autonomy; and Enlightenment and Christian attacks on Judaism as a particularist cult, lacking the universalism of Christian or Enlightenment ideas. None of these claims are particularly hard to refute, and the book includes chapters offering detailed refutations of all three.

Eliminative Anti-Zionism

In a range of further chapters, the book applies the above analysis of the nature and uses of antisemitism to the vexed question of whether certain kinds of criticism of Israel are antisemitic, and if so, what kinds, and why?

Two bad arguments for a negative conclusion are worth dismissing at the outset. The first is that no claim to the effect that any criticism of Israel is antisemitic should be taken seriously, because those who make such claims are motivated by a desire to silence all criticism of Israel. This fails both on logical grounds, because a claim so motivated might nevertheless be true, and on empirical grounds because those who allege antisemitism in specific criticisms of Israel are seldom uncritical of Israel in other ways.

The second argument is that no criticism of Israel can be antisemitic, because antisemitism essentially involves hostility to individual Jews merely because they are Jews, whereas hostility to Israel, being hostility to a state, need involve no hostility to individual Jews. This argument would be sound enough if the definition of antisemitism on which it relies were exhaustive. But clearly it is nothing of the sort. It offers an adequate account of social antisemitism, but none at all of political antisemitism.

The question of whether and what type of criticism of Israel is or might be antisemitic in character thus reduces, according to Blaming the Jews, to the question whether opposition to Israel at any point echoes the traditional claims of political antisemitism. The book argues that this is the case with those strands of progressive left hostility to Israel, self-styled ‘anti-Zionist,’ including the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement, that deny the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish-majority state.

Immediate points of resemblance between this type of anti-Zionism and traditional versions of political antisemitism are that such anti-Zionism targets not individual Jews, but an entire Jewish collectivity, whose existence it holds to be inimical to non-Jewish interests in ways so serious that they can only be addressed by the liquidation of the collectivity in question. In other words anti-Zionism of this type, like all traditional versions of political antisemitism, is eliminative in character. It does not wish to change Israel, but to get rid of it.

A further parallel with traditional forms of political antisemitism is that anti-Zionism of this type regards the allegedly inimical character of the state of Israel as essentially connected with its character as a Jewish state. That follows from the fact that if Jewish majority rule in Israel were to be overthrown and replaced, say, by a Muslim-majority state, anti-Zionists of this stamp would have no further objection to it. A further tenet of most earlier forms of political antisemitism is that the elimination of ‘the Jews’ would automatically bring to an end all those abuses which their supposed dominance over world affairs has allegedly created and furthered. And here again present-day anti-Zionism runs in tandem with such views, given the belief of many of its supporters that the elimination of Israel would immediately result in the inauguration of an era of democracy, peace and plenty throughout the region.

None of this can stand, of course, without some account of the nature of the crimes against humanity supposedly committed by Israel. Since Israel is the only state whose overthrow is demanded by any strand of the progressive left, these must in the nature of things be worse than any that can be alleged against any other presently existing state, including, to name but a few, the present administrations of Myanmar, North Korea or Iran. Against such competition, it would be difficult to make out a case for the superior iniquity of Israel based on listing concrete and specific offenses against human rights. Anti-Zionism of the above type therefore tends to rest its case not, ultimately, on specific acts of this or that Israeli administration, but on a handful of characteristics that it takes to be intrinsic to the nature of the Israeli state, whatever administration, whether of left or right, happens to be in charge at the moment; and intrinsic also, presumably, to its character as a Jewish state. These it takes to include the intrinsic character of the state, since its inception, as an essentially racist enterprise: as a ‘Nazi state’, an ‘Apartheid state’, or a ‘settler-colonial state.’

These are all claims that the widely accepted IHRA definition of antisemitism stigmatises as explicitly antisemitic. But of course they would not be antisemitic if they were true, antisemitism being a form of prejudice, and prejudice being factually ungrounded hostility.

The question whether eliminative anti-Zionism is antisemitic, as the IHRA definition effectively implicitly alleges, effectively reduces, then, to the question whether any of these claims is in fact true. Blaming the Jews devotes five chapters to the attempt to discover some reasonable factual basis for these claims, of Nazism, racism, colonialism, Apartheid; and concludes that there is none to be found. And there is none to be found because, given the very meaning of the terms essential to stating the claims in question, there could in principle be none. Israel is not a racist or an Apartheid state because it accords full citizenship to the 26.5 per cent of its population who happen to be non-Jewish. It is not an Apartheid state because it makes no attempt to keep people of different ‘races’ apart: even the IDF contains thousands of serving members from the Druze and Circassian, Muslim and Christian Arab communities. It is not a settler-colonial state because no originating colonial power stands behind it, and so on.

The conclusion of the book, therefore, is that eliminative anti-Zionism is indeed antisemitic. Indeed, once we add in the constant concern expressed in these circles over the supposed power of ‘the Jewish lobby’ to control entire American departments of state, from the Pentagon to the State Department to the Presidency itself, we are clearly looking at a revived version of political antisemitism complete in all its traditional elements.

The Left

If one asks why this kind of antisemitism should again have become popular on sections of the left, the analysis offered by Blaming the Jews again proves helpful. Left-wing politics by its nature aims at the redemption of what it considers a corrupt society. Before WWII and for a time afterwards, it envisaged that redemption essentially in Marxist economic terms, as the replacement of capitalism with socialism, and itself as the political arm of the urban proletariat. What has largely replaced that older, Marxist, left is a left which frames the vices of capitalism less as the exploitation of the working class than as the malign domination of a multitude of marginalised and excluded groups. At the same time the political power and influence of the left has diminished, on both sides of the Atlantic, to the point at which its most radical supporters are heavily concentrated in the universities. It stands therefore in need of a cause that simultaneously galvanises its supporters, gives it positive access to the media and at the same time explains its failure to gain wider support at higher levels of political influence. Israel offers it the means of satisfying all three needs. Israel can be readily represented as typifying the supposed essential commitment of capitalism to colonialism, Nazism and the exclusion and exploitation of the non-white Other, while at the same time the machinations of the ‘Israel Lobby’ can be advanced as a ready explanation of the failure of the ideas of the left to gain more ready purchase at the highest levels of power.

It is precisely at this point that the lurch into political antisemitism of these sections of the progressive left takes on the potentially lethal, militantly anti-Jewish tinge that many, especially since the Hamas pogrom of 7 October 2023, find reminiscent of Germany in the 1930s. If the radical, BDS-supporting left really believed that Israel is a ‘Nazi’ ‘Apartheid,’ ‘colonialist’ or ‘racist’ state it would have a manifest duty to attack not just Jewish supporters of Israel, but the very much larger body of non-Jewish supporters of Israel, ranging from American Evangelical Christians to very large numbers of conservatives and centrist Labour supporters in the UK. But in fact, as is made clear not only by the recent marches of protest in Britain and the US against the Israeli response to the Hamas atrocities of 7 October, but also by the rash of attacks on perceived supporters of Israel on university campuses on both sides of the Atlantic, those under attack are Jews – and only Jews.

Nor is this in the least surprising. It is no doubt the case that a majority of Jews do support Israel. It follows that no political organisation that incessantly condemns Israel as a ‘Nazi’ or ‘Apartheid’ state can avoid identifying the majority of Jews as supporters of Nazism or Apartheid: that is, as supporters of two movements almost universally admitted to represent the nadir of modern political evil. Of course one is also tarring non-Jewish supporters of Israel with the same brush, and equally absurdly; but they, the non-Jews, can be conveniently excused as fools misled by the all-powerful ‘Jewish Lobby’ – as ‘dumb Goys,’ that is to say, as Norman Finkelstein once called the editor of this journal, for example. The Jews have no such escape. They stand identified by the BDS-supporting left, in the terms made familiar by political antisemitism in all its most lethal manifestations, from the York massacre of Shabbat Ha-Gadol 1190 to the eve of the Holocaust, as an alien nation given over to the pursuit of evils only to be remedied by its summary elimination. That this racist nonsense should be not only believed, but actively promulgated by large sections of a supposedly anti-racist left, would be extraordinary if it did not have such a long history in Western movements aiming at the political or religious redemption of society. It is also manifestly criminal. Those who presently promulgate it must bear a large measure of responsibility for the acute fear of personal attack, including attacks on their children in schools and universities, now being endured by innocent British Jews as mobs including many Jew haters parade through the capital.

It is also relevant that the book offers a final two chapters exploring the vast harms done by political antisemitism not only to Jews, but also to non-Jewish communities harbouring antisemites. But those arguments must be left for readers to discover for themselves.