Remember Baghad, now showing on Netflix, is reviewed by Lyn Julius, journalist and co-founder of Harif, an association of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa in the UK. Lyn is the author of Uprooted: How 3,000 years of Jewish Civilisation in the Arab world vanished overnight.

Since the film ‘ Remember Baghdad’ was made in 2017, the number of Jews in Iraq has gone down from five to three. The film, commissioned by David Dangoor, has been seen by thousands. Now it is likely to be seen by millions on Netflix.

On New Year’s Eve 1946, a young Jewish couple were among the guests at a Benefit Ball in the Iraqi Flying Club. A beauty pageant was taking place: the King of Iraq approached the 21-year old Renée Dangoor, and invited her to take part.

Renée won the contest. Her hand-coloured image of radiant beauty, complete with victory sash, is presently being referenced by 2,700 Arabic websites on Google.

Who would have believed, in bomb-ravaged, sectarian Iraq, that a Jewess could have been crowned Miss Baghdad 1947? ‘Who is even going to believe,’ says Edwin Shuker in the new documentary Remember Baghdad, ‘that there were Jews in Iraq?’

Edwin Shuker is one of the main characters in the film. The opening sequence shows him leaving his home in north London to catch a flight to Erbil, the capital of Kurdistan in the north, in a bid to show that Jews still have a stake in Iraq. Later, we see Edwin in a Baghdadi taxi excitedly giving directions to his driver to find the Shuker family house.

They had abandoned it in haste 46 years earlier.

While the film was being made, the jihadists of Islamic State were just kilometres away. To return to Baghdad for the sake of some footage was a brave, if foolhardy, thing for a Jew to do. Of 140,000 Jews in 1948, only three remain in Iraq in an atmosphere of rampant antisemitism.

This community goes back to Babylonian times when captives from Judea were taken as slaves to the land of the two rivers and remained there for 2,600 years.

The Babylonian Jews had a seminal impact on Judaism as we know it. Yet the community is to all intents and purposes extinct, its members driven into exile and its last synagogue shuttered.

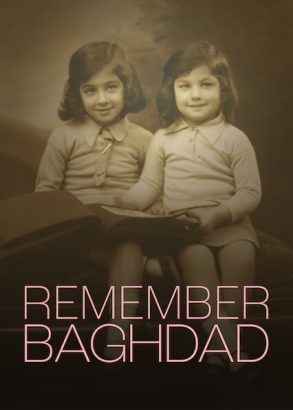

Remember Baghdad started out as a film commissioned by Renée Dangoor’s son David about a group of Iraqi Jews who have been meeting weekly in London over three decades to play volleyball together. Director Fiona Murphy has taken the story to a new level, combining raw material of home movies, family photos and first-person testimonies with rare archive footage – to build a cinematic record of a lost world.

What motivated Fiona, of mixed Jewish-Irish parentage, to make this film? She says, ‘The lives of my parents’ families closed down as the British Empire shattered: my father’s community was thrown out of Ireland and my mother’s fled Jamaica. I grew up in London, conscious that people suffer for the crimes of generations long gone.’ And so ‘when I was between films and was offered a job cataloguing an extraordinary archive of early home movies belonging to an Iraqi-Jewish family I responded vividly to the news that the Jews of Iraq did well under the British, and paid for it. The end of the British Empire was not the only strand that bound their stories together with mine. My mother’s family was ethnically Jewish. And while that was where the historical similarities ended, the smiling faces in the archive and the stark fact that only five Jews remain in Iraq today, awakened my own sense of loss.

She adds: ‘At first I just wanted to convey the pain of losing your home. It seemed important, now, right now, to push back at the narrowness of our news, dominated by discussion of economic migrants, desperate refugees and the difficulties of integrating immigrants. The older stories were laments about the pain of exile: “It’s a Long Long Way to Tipperary”, and “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down and wept”. I wanted to show that that migrants travel with heavy hearts, give them a voice, and bring back the world that was lost. I knew this must be my next film.’

Fiona Murphy’s film came out exactly 100 years after the British invaded what was once Mesopotamia, throwing three Ottoman provinces together to form modern Iraq. One of the country’s chief architects was the British intelligence officer Gertrude Bell, also the subject of a documentary released in 2017: Letters from Baghdad.

Often described as a female Lawrence of Arabia, Bell was a woman in a man’s world. She was the moving force behind the crowning of Emir Faisal as king of Iraq and saw the able, multilingual, educated, and increasingly westernised, Jews, who comprised a third of Baghdad, as the lynchpin of the brave new Iraq she wanted to create.

But the golden age was short-lived for the Jews and was followed by massacre and persecution. Remember Baghdad travelled to Israel to interview the late broadcaster Salim Fattal, the writer Eli Amir, and other survivors of the two-day rampage of June 1941 known as the Farhud – an orgy of killing, rape and looting.

After Iraq introduced a state of emergency in 1948, punishing its Jews for the establishment of Israel, it was primarily fear of another Farhud that spurred 120,000 Jews to leave Iraq for Israel when they had the chance in 1950 and 1951. The price they paid was to be stripped of their citizens’ rights and dispossessed of their property.

Although Iraq remained an implacable enemy of Israel, the 6,000 remaining Jews, who did not flee to the Jewish state, led a charmed life in the 1950s. The film shows clips of home movies depicting one long round of parties and picnics by the river Tigris. The brutal slaughter of the king and his ministers in 1958, their bodies dragged through the streets of Baghdad, came as a shock, but still the Jews did not leave. When they wanted to, in the 1960s, it was too late. By the time the Six-Day war broke out, Jews were effectively hostages of the Ba’ath regime.

The film relates the vengeful terror experienced by the remaining Jews, who witnessed the public hangings of nine of their co-religionists in January 1969 on trumped-up spying charges.

Danny Dallal’s uncle was executed six months later. Scores of Jews disappeared. Danny and Edwin were among the 2,000 desperate Jews smuggled out of Iraq into Iran by Kurds in the early 1970s. They left everything behind.

The film closes with Edwin Shuker signing the contract for the home he has just purchased on a windswept and arid development in Kurdistan. Will he ever live in it? It’s clearly a symbolic act – perhaps the first step on the ladder to buying a property in Baghdad – in order to show the unbreakable bond between Jews and their 2,600 years in the land. You can take the Jew out of Iraq, but you can’t take Iraq out of the Jew.

‘Iraq is in our bones’, says David Dangoor. Regrettably, such feelings of loyalty and affection go unrequited. A recent law passed by an overwhelming majority of Iraq’s parliamentarians suggests that, while other Arab states are burying the hatchet by signing the Abraham Accords, Iraq is going backwards. The new law criminalises any contact with Israel, not just in Iraq itself, but in Kurdistan, which traditionally has had informal ties with the Jewish state. The Iranians are increasing pulling the strings in Iraq and have, reportedly, been taking over Jewish assets and property.

The film’s optimism is somewhat misplaced. No returning Jew would be welcome, let alone safe.

Many Iraqi Jews still suffer nightmares at the thought of what they went through. And the memory of Iraq recedes year by year. Their children and grandchildren, now citizens of Israel and the West, barely understand Arabic: only the food links them with the past. They have moved on.

‘Remember Baghdad’ is an invaluable historical documentary and performs a great service; for the first time, a global mass audience is being introduced to the tragic story of Iraqi Jewry. But the time for nostalgia is over. Perhaps the title should have a question mark after it?