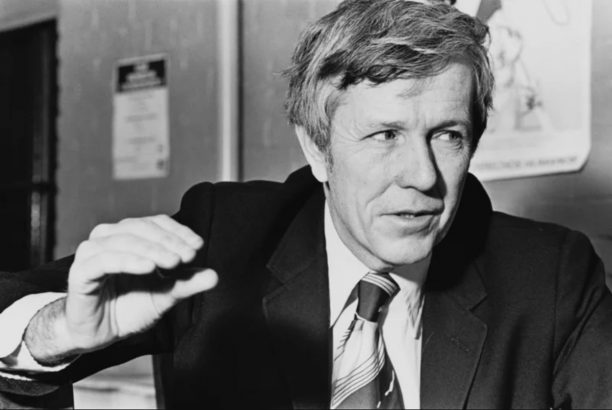

The interview reproduced below, with Michael Harrington (1928-1989), the leading US democratic socialist of the second half of the twentieth century, was first published in fall 1975 by the Jewish Student Press Service. The interviewer, Mitchell Cohen, who went on to co-edit Dissent magazine from 1991 to 2009, has written a new preface for Fathom in which he shares his memories of traveling with Harrington into the West Bank in 1983. The American socialist leader had been on a visit to Israel.Cohen notes the contrast between Harrington’s views about Israel, Zionism and left antisemitism and those of many ‘anti-Zionist’ left-wingers today: ‘It is impossible to imagine him joining those who chanted “From the Jordan to the Sea, Palestine will be free” at a recent Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) convocation’. The editors thank Daniel Holtzman, the editor in chief of New Voices, for granting permission to republish the interview.

New Preface (2020) by Mitchell Cohen

Michael Harrington was America’s most eloquent voice for democratic socialism for decades. His great passion: to create a society that is both economically and politically democratic – a society freed of structurally reproduced inequality. A society, that is, with values that went beyond material benefits and power for its best-off members and social suffering for its least well-off.

But instead of revolutionary grandstanding, Mike Harrington advocated ‘the left wing of the possible,’ insisting on the democratic kernel in Marx’s ideas. Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty in the 1960s is often credited to the impact of Harrington’s classic The Other America (1962). (He thought its failures were due to making a futile war in Vietnam the priority). His last book, finished as he was dying in 1989, was Socialism: Past and Future.

In June 1983 I was in Jerusalem researching a book on the Israeli labor movement’s decline. One evening I received a call from an American friend who had moved to Israel to join a kibbutz. Was I free, he asked, to spend a day in the West Bank with Michael Harrington?

It was Harrington’s first trip to the Jewish state and his hosts were the Israeli Labor party, with which I had close ties, and Mapam (the United Workers’ Party). The American kibbutznik, David Twersky, had been enlisted to take him around. Harrington met leaders of different parties, trade unionists, academics, and Arabs within Israel and the West Bank.

I immediately said yes to the invitation. I had known Mike, although not all that well, since I was a graduate student. I interviewed him for the Jewish Student Press Service in fall 1975, and our conversation was reprinted as a lead in Response (1976) the flagship of the Jewish counter-culture of the late 1960s and 1970s, and elsewhere, and is now republished by Fathom.

It is a document in the history of the American left and follows below. Many in today’s left will be surprised to learn that America’s foremost socialist, heir to the tradition of Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas, saw Zionism as the national liberation movement of the Jews and chastised the UN for branding Zionism a form of racism.

The Jerusalem morning was still cool as we drove into territory occupied by Israel since the 1967 war. As we traveled we talked about the American left as well as what he had experienced in Israel. I had been a member of his organisation, the pro-Civil Rights, anti-Vietnam war Democratic Socialist Organising Committee (DSOC) in the 1970s. (I was late in joining because – I am embarrassed to recall – I did not find it left-wing enough.)

Mike was a remarkable speaker and he laughed when I recalled a particular performance by him I had witnessed. Sometime around 1980 (I don’t remember exactly when), Chemical Bank had taken out an ad in the New York Times. It declared that the real weaknesses of the American economy were due to ‘capital shortage’ in banks. Chemical announced its willingness to debate anyone about it.

A big mistake. Mike said, ok, you’re on. So one evening in a hall off fabled Union Square in New York, the bout took place: the Socialist versus the Banker. In the ring: Harrington and a Vice President of one of the country’s largest financial institutions. The man from Chemical was doubly unfortunate. The microphones didn’t work. His lack of accomplishment before an audience did not enhance his bad arguments. Mike, however, was a first rate orator and his booming baritone simply shredded the ‘capital shortage’ theory. No, the real problem was a pyramid of inequality that reproduced itself on behalf of those on top.

Harrington’s DSOC merged into the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) in 1982, and I joined. Attending one of its founding conventions at Washington Irving High School in New York, I felt good about being in a socialist movement that, though small, seemed smart and anxious for an escape from the considerable mindlessness that swamped the 1960s and post-1960s left.

There were important things to do, in the leftwing of the Democratic party, in the trade unions, among civil rights workers and feminists. Moreover, most DSA leaders I met, like Harrington himself, didn’t parrot the simplistic hostility to Israel that was creeping into too much of the left. The same cannot be said of DSA today. (For an interview with Harrington in Israel see, David Twersky, ‘Michael Harrington: A Vision Writ Large,’ Jewish Frontier, August-September 1983).

A lot had to do with Mike Harrington’s intellectual character. He was a man who valued distinctions; consequently, he made distinctions. He had long been an anti-Stalinist socialist. Communist regimes had caused appalling suffering, in his view, and myths about the Soviet Union or Third World dictators undermined any serious struggle for democracy and equality.

While some socialists twisted and turned to find ways of ‘understanding’ Moscow, he was on the side of east European dissidents. His disdain for apologetics on behalf of Maoism or Third World despots did not dent his passionate concern about Third World poverty. (See his book The Vast Majority). He admired the Olof Palmes of the left, not the Jeremy Corbyns.

Similarly, he understood that it was possible to support the existence of a Jewish state and back its need for security, while dissenting sharply from Israeli government policies. His sympathies were with Israeli and Palestinian doves and not with those in the left who thought that every discussion of Israel had to ascribe to the Jewish state all sin since… well, since sin began.

In fact, it was just a few months before I was with him in the West Bank that he had been an American representative at a meeting of the Socialist International in Portugal when Issam Sartawi, the leading Palestinian dove and advocate of Palestinian-Israeli mutual recognition, was assassinated. Credit for his murder was taken by ‘Abu Nidal,’ an offshoot of the PLO, which had also been partly responsible for the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics in Munich.

Of course Harrington was also thoroughly out of sympathy with the nationalist extremism of right-wing Zionists. If he found the kibbutz attractive and Palestinian terrorism appalling (and not an ‘understandable’ aspect of ‘liberation’), he didn’t conclude that Israel should occupy Palestinian Arabs forever or build settlements.

We talked about all these things as we drove into the Arab town of Beit Jalla, between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. We met there with its mayor. Sipping thick, sweet coffee, we spent an hour or so chatting – I was mostly a fly on the wall – about daily life in conditions of occupation and the possibilities of a resolution to the conflict. The Mayor, I thought, wasn’t entirely frank; I suspected that he did not feel entirely free to speak his mind. He probably wanted some kind of Jordanian-Palestinian federation. Mike asked one question after another and listened attentively to the answers.

Afterwards we drove to Bethlehem, but not only for political reasons. Mike, who wrote a book entitled The Politics at God’s Funeral, was an atheist but had once been a member of the Catholic Workers’ movement. He always retained great affection for it (he had edited its newspaper for a while). He admired its founder, Dorothy Day, and her work against poverty. In Bethlehem, we went to visit the Church of the Nativity, where Jesus was born according Christian tradition. The three of us climbed down stone steps into the Church grotto, with dim lights along the way, to see the famous site. As we left, Mike had an exceptionally bemused look on his face.

Later in the day we had some lunch and made our way back to Jerusalem. David took Mike on to more meetings with political leaders, I went back to archives. I didn’t see him again until I was back in the US. We chatted at an editorial meeting of Dissent magazine (he was on the editorial board) about his trip.

His views remained sharp and discriminating. He remained aware of how complicated the situation was, politically and morally. He knew realities rather than slogans – and never thought in mantras. It is impossible to imagine him joining those who chanted ‘From the Jordan to the Sea, Palestine will be free’ at a recent DSA convocation. (Funny thing about that rant: it virtually inverts the theme song of the Zionist right-wing which, always opposing territorial concessions, insists on possession of: ‘Both Banks of the Jordan.’)

What would he say today about the issues we discussed? I can’t speak for him, but only hazard some guesses, having known something about his ways of thinking. He would have at once been heartened to see the word ‘socialism’ attain new legitimacy in American politics; yet he could only have been disheartened to find too many DSAers repeating some of the worst habits of the old and new lefts. And of course, he would have thought that everything must be done to defeat Donald Trump.

Israel? Surely Harrington would have supported the Oslo accords. Certainly he would have found their unravelling and the ascendancy of Netanyahu and the Likud party very depressing and destructive.

But he was, as once said, ‘a long distance runner.’ (That was also the title of his autobiography). Democracy, egalitarianism, social fairness – these were not short term commitments with which you identified when they were popular and went on to something else when it was more comfortable for you. Michael Harrington never succumbed to what Irving Howe, his close friend, once called ‘curdled realism.’

Mitchell Cohen, February 2020.

*

Democratic Socialism, Israel and the Jews: An Interview with Michael Harrington (1975)

As a writer and as a political figure, Michael Harrington is perhaps America’s most eloquent advocate of democratic socialism. He has criticized both American capitalism and Russian communism with equal harshness. During the past twenty years he has been a leader of the civil and political rights movements. His political activities have ranged from an early involvement in the Catholic Worker movement to having been head of the Socialist Party. His book The Other America, an expose on poverty in the U.S., has been credited as the inspiration for the “war on poverty” in the 1960’s. His last book, Socialism, received much praise and is considered a definitive volume on the topic. It has been translated into several languages including Hebrew.

Currently the National Chairperson of the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee, Harrington advocates the democratic self-organisation of the working class in order to promote a program of socialist reform going ‘beyond the welfare state’. He believes that socialism is not an historical inevitability, but rather a necessity for the future good of humanity. When some groups in the American left took an anti-Israel and anti-Zionist line in the 1960’s Harrington advocated support for Israel on socialist grounds. He defended both Zionism and Israel’s right to exist. In a recent article in the Newsletter of the Democratic Left, which he edits, Harrington expressed outrage at the recent UN resolution equating Zionism with racism. He wrote that,

The basic fact is that Zionism – which I take to mean the philosophy of support for, and identification with, a Jewish homeland in Israel – is the national liberation movement of a Jewish people asserting their right to self-determination. If one preposterously charges that Zionism is racist, then so are all nationalisms which joined to condemn it at the UN. And that is to drain the concept of racism of any serious meaning.

I discussed a number of issues pertaining to Jews, the left and Israel with Harrington at his office near New York’s Union Square. Below the reader will find his views on the key issues of the Middle East, the question of anti-semitism/anti-Zionism and the left, ethnic identity in the United States and other related problems.

Michael Harrington teaches political science at Queens College.

*

Mitchell Cohen: You identify yourself as a democratic socialist. What does this mean, and in particular, how does it affect your views of the international political scene?

Michael Harrington: Being a democratic socialist means favouring the democratisation of economic and social power in the US and the world. Internationally it means solidarity with democratic social forces around the world in the Middle East, Europe, Asia and everywhere. It means solidarity with democratic movements around the world where socialism is not yet on the agenda.

MC: What do you think are the vital issues in the Middle East conflict? In what context do imperialism and self-determination play important roles in it?

MH: I see the issues as essentially being threefold. In the first place there is the issue of Israel’s survival. Second, the rights of the Palestinian people. Third the question of the transformation of the Arab world: raising the standard of living and building socialist and democratic structures.

It is clear from the evidence and the workings of American capitalism in general that American imperialism is pro-Arab. It has been political struggle in favour of Israel that has offset the forces of oil, the State Department and Defence Department. In this sense the US has not followed its economic interests. If you read Harry Truman’s memoirs you’ll see that both the State Department and Defence Department were against Israel in 1948. If the US was acting on the basis of imperialist consideration alone, such as oil, Washington should not be supporting the creation of Israel.

There is a legitimate Palestinian right to self-determination, no matter how you look at past history. Today there is a Palestinian identity. And I support the right of all people, including the Jews, to self-determination.

The problem is that there is a conflict between Jewish and Palestinian self-determination. Both want the same land, yet both cannot have self-determination on the same spot. I think that the best long-range solution in terms of both politics and justice is a two-state solution. We might talk at a later time of a federation, but in any event there must be a Palestine and there must be an Israel with defensible borders. And borders are not necessarily to be determined by what was in 1967 or 1948. What is needed is a politically and economically viable Israel.

There is still another problem. The natural Palestinian state is Jordan. British and US policy with the Hashemite Kingdom has been to maintain the independent Bedouin regime. But the most rational outcome for the Palestinians would be in the West Bank and Jordan. A Palestinian mini-state in the West Bank alone would have as its raison d’etre expansion into Israel. However a mini-state might be a transitional necessity.

MC: What should the American role in the Middle East be?

MH: First, the US should supply Israel with the necessities for defending itself. Second, the US does have a peacekeeping role. A political settlement in the Mideast is the only possible settlement. Israel has to make concessions as well and can’t stand on the 1967 conquests. On the other hand, an Israeli rollback must entail some believable guarantee that will eliminate the fear of being attacked in the near or the foreseeable future.

Egypt has severe economic problems and the Israeli willingness to rollback can lead to some progress. With Egypt there is a possibility, not of total peace right now, but of a truce. The US can have a peacekeeping role and I am in favour of sending American technicians to Sinai as part of the recent interim agreement.

MC: Some people on the Left have paralleled the Middle East conflict with Vietnam. Do you think this a valid analogy?

MH: No. At the height of American involvement in Vietnam, which I opposed as far back as 1954, I always said that there was no analogy at all. My objection to US policy in Vietnam was out of opposition to Washington’s policy of support to reactionary and dictatorial regimes. You know, Nixon made the reverse argument that if you support Israel, you must also support regime such as Thieu’s. This is equally invalid.

I support Israel as an internationalist. Israel is a democratic country whose people are passionately defending its self-determination.

MC: Much of the American Left – in particular what was the New Left – is regarded as being hostile to Israel’s very existence. How do you explain this?

MH: A good part of the American Left, in the name of socialism, developed a type of Third World romanticism. They saw the Third World as homogenous, which it isn’t, and had an attitude of the US always being bad and the Third World always right.

I think the anti-Israel attitude of some of the Left is also in part a result of Israeli policy between the two wars, from 1967 to 1973. Israel’s denial of Palestinian rights and intransigence when in a position of strength incorrectly convinced some that Israel was basically wrong. My attitude, as a supporter of Israel, is one of identification with Israelis like Yitzak Ben Aharon and Shlomo Avineri who have argued that risks must be taken for peace.

There is also a dimension of Jewish anti-Semitism on the Left. It’s a cliché already but some young Jewish leftists, feeling a need to prove their commitment to socialism and internationalism, had to be more anti-Israel than anyone else. Jews have played an important role in the American Left and some of them have played an important role in the anti-Israel line.

Nonetheless, it is wrong to say that the entire Left is anti-Israel. This is simply not so.

MC: Why is so much of the left hostile to Zionism as a political, national movement? It is somewhat disturbing that many of those people responding to Jewish issues and concern for Israel seem to come from the right.

MH: There is some confusion as to what Zionism means for many people. I disagree with the concept of ‘exile’. My wife is Jewish and so are my children according to Jewish law and I don’t regard them as being in exile. Romantic nationalism of Herzl’s type should not be confused with the Jewish right of self-determination which I ardently support.

I think that it would be a tragedy if the cause of Israel is identified with anti-détente and Scoop Jackson. Jews and everyone else have a stake in the prevention of nuclear war. Our dealings with the USSR, of course, cannot be a one-way street and détente must include the right of emigration.

I don’t have the Solzhenitsyn view of the USSR. Mine is closer to Medvedev’s (Editors’ note: Roy Medvedev, author of Let History Judge, is a socialist and vocal dissenter in the Soviet Union). Détente is not going to bring democracy in the Soviet Union. But there is still the hope.

MC: How should progressive Jews respond when confronted with anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism on the Left? How do you respond to it?

MH: Obviously fight it. But fight it in left-wing terms. Insist on the right of Jewish self-determination. Point the finger at the role of oil companies. Turn the ‘imperialist’ argument against those who use it. I support Israel in classic left-wing terms. It’s imperative not to move to the right to fight attacks on the left.

MC: Do you think there is a significant amount of anti-Semitism on the anti-Zionist left – meaning not necessarily Jews – position on Israel and Jewish concerns?

MH: You have to be very careful on that issue. Take the Socialist Workers Party (Editor’s note: The Socialist Workers Party is an ‘old left’ Trotskyist Party whose youth group is the ‘Young Socialist Alliance.’). The SWP has a terrible line in Israel. But they should not be approached as anti-Semites. They are acting ideologically with an anti-Israel conclusion, not through anti-Semitism. It is wrong to say that anyone criticising Israel is anti-Semitic. If that was the case, many Israelis would be anti-Semitic. It’s similar to the way the world ‘racist’ was thrown around on the Left. The word ‘anti-Semite’ should not be used in indiscriminate ways. It cuts out dialogue.

MC: How would a democratic socialist view perpetuation of ethnic identity and community in the US? Is it necessarily divisive for progressive forces?

MH: As a socialist I believe that all people must unite on the basis of social class needs. Workers of all ethnic and national backgrounds must get together. At the same time people who want to assert their identities have every right. But many ethnic movements are class movements in disguise. For example, the anti-Black movement of South Boston Irish has a socio-economic background. Politically, I want to bring people together and at the same time have complete and full freedom of ethnic expression. But it shouldn’t be disguised as economic and class action.

MC: How does this correspond to general socialist notion of internationalism?

MH: One formula socialist have used is that struggle is national in form, international in context. You can’t wish away national identity. Marx was wrong on this point of class and nation. He thought that national identity would become less potent when it did just the opposite. The thing is more a question of opposing the nationalism of one nation being used to hurt another. Jews, Poles, Irish, etc. should have a right to organise themselves culturally etc. but this should not be used to injure others. Recent ethnicity has largely developed in working class neighbourhoods, often near the Black ghetto, as a response to a perceived threat.

MC: Historically, there have been many contradictory writings by socialists on Jewish issues. Marx’s essay on the Jewish question (1843) has been construed as blatantly anti-Semitic. In the early years of the Russian Social Democratic movement, at the turn of the century, Lenin opposed the Jewish Workers Bund when it wanted to be separate within the movement as a representative of Jewish workers. For Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxembourg, Jewish concerns were of minor interest. Stalin’s politics were openly anti-Semitic. Why would this ambiguity and perhaps less than compassionate attitude towards an obviously persecuted minority?

MH: For the sake of scholarly detail, Marx used his language terribly. It is objectively anti-Semitic. But taken in its historical context, Marx intended his essay to be pro-Semitic. He was arguing against the writings of Bruno Bauer, who was refusing to defend Jewish rights. Marx was not an anti-Semite. He was a cosmopolitan intellectual internationalist and anti-nationalist. Marx never thought much about his Jewish identity.

There has been a profound Russian anti-Semitic tradition. Stalin used it against Trotsky and all the way through the Doctor’s Plot of the 1950’s. (Editor’s note: In 1952-53 a group of doctors, almost all of whom were Jewish, were charged with trying to poison Stalin. Only Stalin’s death in the winter of 1953 prevented what would have almost certainly been an extensive new ‘purge’ of Soviet Jewish intellectuals). On the question of the Bund, it is a theoretical question. I sympathise with the Bundist position but there are non-anti-Semitic reasons for opposing it.

The record of Marxist and socialists in France and Europe does not bear out any general anti-Semitism on the Left. Socialists were an important part of the anti-Fascist struggle in Europe. Although that has been some anti-Semitism on the Left, the socialist idea is not intrinsically anti-Semitic in any way. But there are cases, such as the Austrian Social Democratic movement before World War Two, where there was anti-Semitism on the part of some workers following the defeat of the party which was dominated by Jews.

On the balance, however, the socialist movement has not been anti-Semitic.

MC: How do you appeal to middle class or post-immigrant middle class groups, such as large section of the American Jewish community, to support democratic socialism which might easily be perceived as against their interests?

MH: There are two ways. First, the middle class in general has gone through college. Rational argument and moral values must be employed. You cannot assume that everyone follows a narrow conception of economic self-interest.

Second, socialist ideas are directed not at the middle class. Nelson Rockefeller should think twice about joining the socialist movement. He isn’t going to join anyway. Socialism involves the confiscation of great fortunes. It is morally indefensible that one man should have such wealth and others should have next to nothing.

In any event, what I want to see done is not a levelling of the middle class but the bringing up of the poor and working class. Internationally, we do not aim at levelling up the US, but at bringing up the Third World.