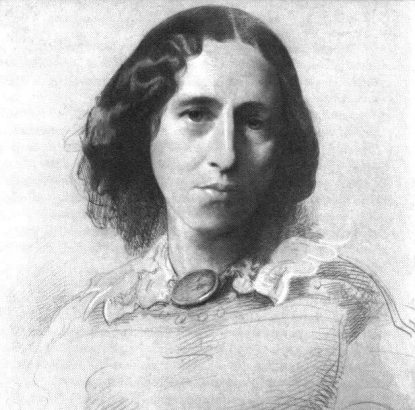

The impact of George Eliot’s 1876 novel Daniel Deronda was central to the coalescence of the first Zionist movement, Hovevei Zion, in the early 1880s. Later, pioneer Zionist Nahum Sokolow wrote: ‘In the Valhalla of the Jewish people, among the tokens of homage offered by the genius of centuries, Daniel Deronda will take its place as the proudest testimony to the English recognition of the Zionist idea.’ In this essay, in honour of the 200th anniversary of Eliot’s birth, Philip Earl Steele examines the influence of the novel on the nascent Zionist movement and locates it within the wider movement of 19th century British Christian Zionism.

Introduction

In the introduction to her recent lecture-series on Daniel Deronda by George Eliot, Harvard Professor of Yiddish and Comparative Literature Ruth R. Wisse stated: ‘Twenty years before the rise of Zionism, [Eliot] put forth the idea that Jews had to reclaim their national sovereignty in the Land of Israel’.

Theodor Herzl, however, speaking at the close of the First Zionist Congress held in Basel on 31 August 1897, even before he gratefully acknowledged the pioneering role of many Jewish Zionists, said: ‘We must, moreover, thank the Christian Zionists.’

Indeed, Zionism, understood as an idea coupled with effort on behalf of creating a Jewish state in Palestine, came into fruition in the early decades of the 19th century among British Evangelical Christians, as Israeli scholar Anita Shapira has stressed. Though among such Christians (and Jews) this aim was known as ‘Restorationism’, in keeping with Herzl’s own usage (and Max Nordau’s remark from 1905 – ‘Zionism is a new word for a very old thing’), I typically observe the longstanding practice of using the term ‘Zionism’ and its kindred forms in regard to the entire period preceding Herzl.

Much has been said and written about George Eliot’s final novel Daniel Deronda, published just four years before she passed away at 61. However, surprisingly little of the novel’s powerful impact on the early Zionist movement has been described. This is odd as – together with the efforts of other British Christian Zionists (particularly Laurence Oliphant and Rev. William Hechler) – the impact of Daniel Deronda was central to the coalescence of the first Zionist movement, Hovevei Zion, in the early 1880s, as I recently described in a research paper available in Polish. Here, in an adaptation of that work, I focus only on the reception of George Eliot’s novel as one important example of the debt owed by the Zionist movement to British Christians in the period before the establishment of Mandate Palestine following the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

British Christian Zionism and Daniel Deronda

The influence of Daniel Deronda on the first Aliya is neglected by literary scholars. Many treat Eliot’s novel as an anomaly, stressing instead that the figure of the Jew had hitherto been treated everywhere as a schwarzcharakter – Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (1600) and Fagin in Dickens’ Oliver Twist (1839). Seldom are the Jewish heroes of Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) recalled, nor that in the early 1860s, Dickens removed the unpalatable descriptions of Fagin from renewed printings of Oliver Twist, and that in his Our Mutual Friend (1864-65), the Jewish character Mr Riah is portrayed as a model of virtue.

Also worthy of attention is the presence of the Zionist idea in English poetry of the 19th century – for instance, in Byron’s Hebrew Melodies (1815) and Browning’s Holy-Cross Day (1855). Among Byron’s Melodies is the poem ‘O, weep for those!’, which, as Sheila A. Spector found, was translated into Hebrew and Yiddish more than 20 times:

O! weep for those that wept by Babel’s stream,

Whose shrines are desolate, whose land a dream;

Weep for the harp of Judah’s broken shell;

Mourn – where their God that dwelt the godless dwell!

And where shall Israel lave her bleeding feet?

And when shall Zion’s songs again seem sweet?

And Judah’s melody once more rejoice

The hearts that leap’d before its heavenly voice?

Tribes of the wandering foot and weary breast,

How shall ye flee away and be at rest!

The wild-dove hath her nest, the fox his cave,

Mankind their country – Israel but the grave!

The Zionist leader and historian of early Zionism Nahum Sokolow (1859-1936) dubbed the final two lines of this poem a ‘Zionist motto’, and claimed that in Hebrew ‘there are no lines more popular and more often quoted’.

Many scholars of Daniel Deronda are simply unaware of the striking power and scope of Christian Zionism in 19th-century Britain. They seemingly believe that the Zionism in Eliot’s work appeared serendipitously and without context, despite the fact that Restorationism was ubiquitous in 19th-century British politics and culture, one that owed its strength to Evangelicalism, the faith George Eliot (more correctly, Mary Ann Evans) had been imbued with.

The belief that – in accordance with Biblical prophecies – the Jewish people would one day return to their ancient homeland had accompanied British Protestantism since its inception in the 16th century. However, this belief became a political objective only after the Napoleonic Wars, once Britain had become a powerful global empire possessing the means to contribute to the restoration of a ‘national home for the Jewish people’ in Palestine. We then see a combination of religious belief and imperial policy on behalf of the Zionist idea. For example, in 1833, when the Ottomans were losing their hold on the Levant, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Archbishop of Dublin explained in the House of Lords that the Bible states things plainly: the Jews were once again to establish their own state in Palestine. Moreover, Britain was to play a surpassing role in this enterprise. Indeed, from the 1830s, philosemitism and Christian Zionism sunk ever stronger roots in both British identity and policy.

The most outstanding British Christian Zionist in the 19th century was Anthony Ashley-Cooper (1801-1885), Lord Shaftesbury from 1851 . He was also the most important social reformer of his day, promoting laws of historic significance concerning the mentally disabled, children, women and mineworkers. We might well picture Dickens in the role of legislator. Though, Shaftesbury was above all actively committed to the restoration of the Jews to Palestine – in Parliament, the press and Evangelical organisations. As the son-in-law of former Prime Minister of Great Britain, Lord Palmerston, Lord Shaftesbury enjoyed Palmerston’s active support. For example, Lord Shaftesbury had a leading role in establishing the British Consulate in Jerusalem in 1838 and founding the joint Anglican-Lutheran bishopric with Germany in 1841, believing that these matters would contribute to the development of Jewish settlement in Palestine and precipitate the return of Jesus. In February of that same year – 55 years (virtually to the day) before Herzl’s Der Judenstaat – he published in the British Colonial Times a ‘Memorandum to the Protestant Powers of the North of Europe and America’, appealing for the convening of an international congress with the purpose of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine.

Restorationism was everywhere to be found in mid-19th-century British society. For example, in 1865, archaeologists and clergymen set up the Palestine Exploration Fund, which conducted wide-ranging research into Biblical sites – with Lord Shaftesbury one of the founders. The discoveries made by the Fund were regularly noted in the press, thereby keeping the attention of Evangelicals pinned on the Holy Land. The list of Brits who, starting in the 1830s, tabled serious plans for the Jewish settlement of Palestine is astounding in length, and (to mention only a few individuals) includes Alexander McCaul, Samuel Bradshaw, Edward Bickersteth, A.G.H. Hollingworth, Charles Henry Churchill, George Gawler, Charles Warren and Claude Conder.

Oliphant’s Plan

Laurence Oliphant, who enjoyed a high standing in the British establishment, presented Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli and the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Lord Salisbury, with his ‘Plan for Gilead’ in 1879. The plan – which postulated the Jewish colonisation of the northern lands of Biblical Israel – was then published as a book in 1880 under the title The Land of Gilead. Oliphant even won an assurance of £40,000 for the enterprise from the Palestine Exploration Fund, which would arise as a 25-year lease. Thanks to the support of Disraeli and Salisbury, in 1879 Oliphant left to explore the Levant. Once his investigations were complete, he travelled to Istanbul where he sought a firman –the permission of the Turkish Sultan – for the settlement in Gilead of a Jewish colony. Though having failed in that bid, Oliphant tried again in 1882 and 1883 in the wake of the 1881 pogroms. He worked directly with Jewish refugees in the Pale of Settlement and co-operated with the newly arisen Hovevei Zion societies there and in Romania.

The Impact of Daniel Deronda

George Eliot published Daniel Deronda in 1876. The titular hero is a young English gentleman who discovers his Jewish origins and becomes captivated by the Zionist vision of a Jewish mystic named Mordechai/Ezra. Ultimately, he determines to dedicate his life to building a Jewish national home in Palestine. The novel, which was rapidly translated into numerous languages – there were three translations into Russian within a year alone – commanded enormous popularity within the Diaspora and inspired leading Zionists including Albert Goldsmid, leader of Hovevei Zion in Britain, and Emma Lazarus, the American poet who penned the famous verse found at the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. On the continent, Deronda inspired an untold number of Jewish readers. Worthy of mention among the more prominent are: the financier Haim Guedalla ( a close nephew of Moses Montefiore), who in 1876 was drafting plans to finance Ottoman debt and, inspired by the instalments of Daniel Deronda he was avidly reading, revised his plan and built them around persuading the Turks to sell vast tracts of ‘Syria’ for Jewish settlement. Indeed, that autumn he initiated correspondence with George Eliot, in the course of which the two remarked, with obvious delight, on the consonance of their ideas; Rabbi Professor David Kaufmann of Budapest, who published a significant tract on the novel in 1877; Moritz Schnierer, who together with Nathan Birnbaum went on to found the Viennese group of student-Zionists, Kadimah, in 1883; Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew; and Peretz Smolenskin, the publisher of the highly influential Hebrew-language journal Ha-Shahar (Vienna). As his diaries indicate, Theodor Herzl also acquainted himself with Daniel Deronda, and prior to writing Der Judenstaat. Among the many other Jews upon whom Eliot’s novel exerted an influence were such writers as Isaac Leib Peretz and Abraham Goldfaden, and none other than the fathers of modern Israel David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann (who kept the novel ‘within easy reach’ in his bedroom).

David Frischmann’s Hebrew translation of Daniel Deronda was published in 1893 in Warsaw. However in December 1876, the British press reported that the leading Hebrew-language weekly Ha-Magid, published by David Gordon in Ełk (north-eastern Poland), had been printing important fragments of the novel in Hebrew, ones that were being republished in the Hebrew press in Germany, Russia, Poland and even Jerusalem. In 1877, Daniel Deronda appeared in German and Dutch, and in 1878 Calmann Lévy published it in French. By 1883 there was even an Italian translation.

On the basis of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s autobiography A Dream Come True (available only in Hebrew), Shalom Goldman wrote:

Ben Yehuda … tells of the rabbinic education he rejected and of the secular Jewish nationalist vision that replaced it. His life task … would be ‘the restoration of Israel and its language on the land of its ancestors’. To his dismay, Perlman/Ben-Yehuda’s Orthodox yeshiva teachers and fellow students rejected his Zionist ideas. One yeshiva friend, though, did not reject him. Rather, he told Perlman of ‘an English story he had read in the monthly Russian journal Vestnik Evropi in which a man was described who had a vision similar to [Perlman’s] own … It was the novel Daniel Deronda, by George Eliot’. ‘After I had read the story a few times’, Perlman wrote, ‘I made up my mind and I acted: I went to Paris … in order to learn and equip myself there with the information needed for my work in the Land of Israel’.

The Polish-language Jewish weekly Izraelita – which advocated assimilation – noted Daniel Deronda in its final edition of 1876 and published a very positive review in the first edition of 1877. However, in July 1877, Izraelita published a 19-page review in three installments entitled ‘Genjalne złudzenie’ – ‘A brilliant illusion’. The first instalment read:

Not since Lessing wrote Nathan the Wise have Judaism and its adherents obtained such a full and just appraisal as in this work. What most astounds is the vast knowledge of Judaic literature, beginning with the Bible and the Prophets – and extending to the most recent works of the German school. The lady-author knows the Talmud, the Midrash and Kabala. She often quotes passages from those collections and interprets them in a way so apt and original that it would bring honour to many a Talmudist or preacher by vocation.

However, regarding the Zionist vision held up in Daniel Deronda, the reviewer does not conceal their perplexity: ‘The brilliant and learned author, by lineage and faith a Christian woman, is an advocate of the idea of rebuilding the national life of the Israelites!’. In the third instalment, the reviewer grapples with the viability of Eliot’s idea – and rejects it:

The authoress shows how Deronda, slowly freeing himself from prejudice toward the Jews, over the course of acquainting himself with their customs, studying their writings, and becoming initiated into the ideas of Mordechai, transforms into a gladiator for Judaism and stands ready to take the helm of the Jewish ship, in order to rekindle the Jews’ national feeling and rebuild their unity and autonomy. The author wished to show what is working against the Jews of today’s epoch, and at the same time to point out what they should pursue. On that fine day when the Jews will come to that recognition, when they will be capable of rising to the heights of national fervour and follow one such as Deronda – on that fine day the novel about the young pair [Daniel and his wife, Mira] heading off to the Holy Land in order to bring Mordechai’s mystical dreams to life will be ripe for continuation.

… It seems certain, however, that in regard to the reality now unfolding of the state and social life of peoples, and of the inseparable portions of the Jewish race; that in regard to civilisation and science levelling all possible social irregularities; and lastly, in regard to the assimilationist trend that has appeared in the state field, and which drives not toward atomizing and separating, but toward uniting and gathering scattered elements – in light, as I say, of these irresistible manifestations of real life, ones which no doubt are the result of the unchanging law of humanity’s development – a law that we dub ‘the Divine idea in history’ – the notion of Mrs. George Eliot to rebuild the state life of the Jews, no matter how fiery its expression and no matter the rapturous power of its inspired words, is and shall remain but a – brilliant illusion…

The Polish-Jew and Zionist Nahum Sokolow – an early Hovev Zion (lover of Zion), observer at the First Zionist Congress in Basel, luminary of Hebrew journalism and president of the World Zionist Congress from 1931 to 1935 – devoted much space in his two most important historical works (History of Zionism 1600-1918, vols. 1 & 2, 1919, and Hibbath Zion – The Love for Zion, 1935) to the role of Christians in the development of Zionism. For example, when the British Mandatory Palestine was coming into being, Sokolow (echoing Rabbi Professor David Kaufmann’s words) wrote this of Eliot’s novel:

Among English writers who have understood the [Zionist] idea in all its depth and breadth, the place of honour belongs unquestionably to George Eliot (1819-1880). She chose the Zionist idea for the theme of an imaginative creation, wherein she displayed unequalled depth of comprehension and breadth of conception. In Daniel Deronda … the Jew demands the rights pertaining to his race, and claims admittance into the community of nations as one of its legitimate members. He demands real emancipation, real equality. The blood of the prophets surges in his veins, the voice of God calls to him, and he becomes conscious, and emphatically declares that he has a distinct nationality; the days of levelling are over. Where calumny and obtuseness see nothing but disjecta membra, the eye of the English poetess perceives a complete national entity destined to begin life afresh, full of strength and vigour … In the Valhalla of the Jewish people, among the tokens of homage offered by the genius of centuries, Daniel Deronda will take its place as the proudest testimony to the English recognition of the Zionist idea.

Judaism, Christianity and George Eliot

Eliot’s mature fascination with Jews and Judaism became earnest in 1866 upon meeting Emanuel Deutsch, the outstanding scholar and Hebraist born in today’s Nysa (southern Poland). While employed at the library of the British Museum, he wrote his renowned work ‘The Talmud’, which was published in the Quarterly Review in 1867 to great acclaim. Deutsch had shared the paper’s rough-draft with Eliot, who called it ‘glorious’. As Professor Gertrude Himmelfarb author of The Jewish Odyssey of George Eliot, recently recounted, it was under the careful eye of her new friend that Eliot learned Hebrew. Deutsch also ‘introduced her to ancient Jewish sages and modern Jewish scholarship, and spoke eloquently of his vision of national redemption in Palestine’. Indeed, Deutsch was the model for Daniel Deronda’s Mordechai. In 1872, Eliot threw herself into ‘a massive work of research into Jewish learning and lore. Eliot’s notebooks for this period contained excerpts from the Bible and Prophets, the Mishnah and Talmud, Maimonides, medieval rabbis and Kabbalistic works, as well as contemporary German scholars (Moses Mendelssohn, Heinrich Graetz … ), French scholars (Ernest Renan, Jassuda Bédarride … ), English scholars (Henry Milman, Christian David Ginsburg, Abraham Benisch … ) and scores of others’.

Does the label ‘Christian Zionist’ truly apply to Eliot? After all, she is sometimes portrayed as an atheist, and at the very least as someone who had abandoned Christianity. Hence the ‘watered-down’ descriptor ‘Gentile Zionist’ one sometimes meets. The form of Christianity in which Eliot was raised was Evangelicalism. As an 8-year-old, she began to attend ‘a boarding school, where an Evangelical teacher instilled in her the habit of the daily reading of the Bible and study of the Scriptures’, writes Himmelfarb. ‘Transferred to another school four years later, she encountered a more rigorous Calvinistic form of Evangelicalism … Returning home at the age of 16 … she brought with her that religious and moral earnestness. Three years later, on her first visit to London with her brother … she refused to accompany him to the theatre, spending the evening instead reading Josephus’s History of the Jews’.

As it oft-times happens, Eliot later passed through a period of rebellion toward the religion inculcated during her girlhood. In her case, this rebellion had a markedly intellectual character. She fell in with a milieu of freethinkers, thanks to whom she discovered the higher Biblical criticism then developing, especially in Germany. In 1842, she began the translation of Das Leben Jesu by David Strauss into English: the final version (numbering approximately 1,500 pages) was published in 1846. As Himmelfarb notes, ‘her immersion in Strauss had given her a more acerbic view of both Christianity and Judaism – and of religion in general’.

Eliot’s father died in the spring of 1849 (her mother had passed away 14 years earlier). Soon after finding herself parentless, she departed with married friends on a trip to Geneva, where she was to live from that July until March the next year. In October, now without her friends, she took a room at the home of the painter François D’Albert Durade and his wife. In fact, the well-known portrait of the young, pretty Eliot was Durade’s work.

That Eliot was unabashed about her animosity toward religion while in Geneva is altogether plain from the correspondence between her and Durade ten years later, in late 1859, when she was 40-years-old. In a letter to Eliot, Durade expresses his surprise that her latest novel Adam Bede (which Leo Tolstoy categorized as ‘religious art … flowing from love of God and man’) evinced such a strong sympathy for religion. Eliot’s response was this:

I can understand that there are many pages in ‘Adam Bede’ in which you do not recognize the ‘Marian’ or ‘Minie’ of the Geneva days. We knew each other too short a time, & I was under too partial and transient a phase of my mental history, for me to pour out to you much of my earlier experience. I think I hardly ever spoke to you of the strong hold Evangelical Christianity had on me from the age of fifteen to two&twenty & of the abundant intercourse I had had with earnest people of various religious sects. When I was at Geneva, I had not yet lost the attitude of antagonism which belongs to the renunciation of any belief – also, I was very unhappy, & in a state of discord & rebellion towards my own lot. Ten years of experience have wrought great changes in that inward self: I have no longer any antagonism towards any faith in which human sorrow & human longing for purity have expressed themselves; on the contrary, I have a sympathy with it that predominates over all argumentative tendencies. I have not returned to dogmatic Christianity – with the acceptance of any set of doctrines as a creed & a superhuman revelation of the unseen, but I see in it the highest expression of the religious sentiment that has yet formed its place in the history of mankind, & I have the profoundest interest in the inward life of sincere Christians in all ages. Many things that I should have argued against ten years ago, I now feel myself too ignorant & too limited in moral sensibility to speak of with confident disapprobation: on many points where I used to delight in expressing intellectual difference, I now delight in feeling an emotional agreement. On that question of our future existence, to which you allude, I have undergone the sort of change I have just indicated, although my most rooted conviction is, that the immediate object & the proper sphere of all our highest emotions are our struggling fellow-men & this earthly existence.

Conclusion

Daniel Deronda was a spark that ignited the imagination of the Jewish Diaspora from Britain to Russia. Though those who wished to travel to Palestine were a small minority of the Jews fleeing the pogroms of the early 1880s, in many cases they had been inspired to do so by Eliot, and thus were all the more willing to respond to the outreach efforts led in the Pale and Romania by the Christian Zionists Laurence Oliphant and Rev. William Hechler.

As Paul Johnson concluded, ‘in terms of its practical effects [Daniel Deronda] was probably the most influential novel of the nineteenth century’. The novel powerfully argued that the Jews are a people, a people with a praiseworthy religion and past, and thus deserving of a shining future – again in their ancient home. The novel’s universal message is that devotion to society, to one’s own community – to something greater than oneself – can impart the life of the individual with a deep, indeed redeeming, significance.

Bibliography

Beth-Zion Lask Abrahams, ‘Emanuel Deutsch of The Talmud Fame’, Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England) Vol. 23, 1969-1970, p.53-63.

Yaakov Ariel, An Unusual Relationship: Evangelical Christians and Jews, New York University Press, New York, 2013.

Norman Rose, Chaim Weizmann: A Biography, Viking, 1986

George Eliot to François D’Albert Durade, 6 December, 1859. British Library, Egerton MS 2884.

Shalom Goldman, Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, & the Idea of The Promised Land, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2009.

Nancy Henry, The Life of George Eliot: A Critical Biography, Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, 2012.

Gertrude Himmelfarb, The Jewish Odyssey of George Eliot, New York-London: Encounter Books, 2009.

Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, Harper & Row, New York, 1987.

Franz Kobler, The Vision Was There, A History of the British Movement for the Restoration of the Jews to Palestine, World Jewish Congress, London, 1956.

Alan T. Levenson, ‘Writing the Philosemitic Novel: Daniel Deronda Revisited’, Prooftexts, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Spring 2008), Indiana University Press, p.129-156

Donald M. Lewis, The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury and Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010.

Boris M. Proskurnin, ‘George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda and the Jewish Question in Russia of the 1870s–1900s’, Literature Compass, vol. 14, no. 7, July, 2017.

Anita Shapira, Israel. A History, Brandeis University, 2012.

Robert O. Smith, More Desired Than Our Owne Salvation: The Roots of Christian Zionism, Oxford University Press, New York, 2013.

Nahum Sokolow, History of Zionism, 1600-1918, vol I & II, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1919.

Nahum Sokolow, Hibbath Zion (The Love for Zion), Rubin Mass, Jerusalem, 1935.

Sheila A. Spector, Byron and the Jews, Wayne State Univ. Press, 2010.

Philip Earl Steele, ‘Henry Dunant: Christian Activist, Humanitarian Visionary, and Zionist’, Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, 2018, p.81-96.

Philip Earl Steele, ‘Syjoniści chrześcijańscy w Europie środkowo-wschodniej (1876-1884): Przyczynek do powstania Hibbat Syjon, pierwszego ruchu syjonistycznego’ [Christian Zionists in Central-Eastern Europe (1876-1884): A Commentary on the Birth of Hibbath Zion, the First Zionist Movement], in Żydzi Wschodniej Polski, Seria VII, Między Odessą a Wilnem: Wokół Idei Syjonizmu, Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, 2019, p.105-138.

The Executive of the Zionist Organisation, The Jubilee of the First Zionist Congress, 1897-1947, chapter ‘The Proceedings of the First Zionist Congress’, Jerusalem, Oct. 1947, p.63-84

Lyof Tolstoi, What is art?, Thomas Y, Crowell & Co., New York, 1899.

Michael K. Silber, ‘Alliance of the Hebrews, 1863–1875: The diaspora roots of an ultra-Orthodox proto-Zionist utopia in Palestine’, The Journal of Israeli History, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2008, p. 119-147.

Superb article.