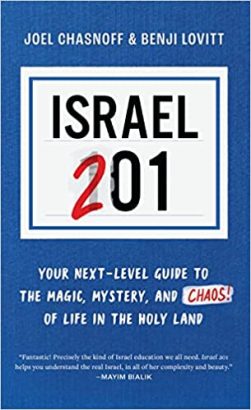

The world has reached a saturation point with Israel 101 books. We have enough options to guide readers through basic information about contemporary Israel’s history, politics, culture, population, and geography, each written from a mildly different perspective and employing various approaches to appear dispassionate. An author can update the information these texts contain or attempt to shift their approach or emphasis, but essentially, they do not change. The next logical leap to learn about Israel is monographs of a higher level of abstraction or with a narrower focus directed at an audience seeking expertise on a topic of interest related to Israel. But neither the 101s nor the scholarly monographs are sufficiently compelling or relevant for those educated lay readers who are most curious to understand how Israel really functions in a vivid, authentic, boots-on-the-ground way, as told by ordinary people, and without excessive scaffolding, framing, or political apologia. For this broad readership, Joel Chasnoff and Benji Lovitt offer us Israel 201: Your Next-Level Guide to the Magic, Mystery, and Chaos of Life in the Holy Land.

In Israel 201, the authors peel back the curtain and expose fine-grained daily life and the memorable, odd, sometimes touching details that make Israel what it is and Israelis collectively who they are. Chasnoff and Lovitt accomplish this while explicitly acknowledging up front that they will not centre on the occupation (‘the O-word,’ as they call it) or the conflict. Instead, they selected 75 topics of interest to discuss and did not look back. The book is unabashedly written by two American olim (Jewish immigrants). The authors have the advantage of ultimately adjusting to their lives in Israel but can still vibrantly translate their experiences to readers with fellow Anglo sensibilities. However, Chasnoff and Lovitt decided not to narrate alone. They also solicited the aid of Israeli interviewees to collect more data and insights.

At first, I was sceptical that Chasnoff and Lovitt could effectively pull a 201 off, that it might just be a gimmick to offer the same introductory information dressed up differently. But by the time I finished, I was convinced that the world needs their 201, especially since the authors do an exceptional job of revealing details illuminating the charm of contemporary Israeli culture while unafraid to expose some of the country’s real difficulties, irritations, and dangers. In doing so, the book bounces around energetically from one topic and vignette to the next, using eight (sometimes loosely) thematic clusters to organise chapters (like ‘Government, Social Policy and Education’ or ‘The Economy, Work, and Work-Life Balance’). The local experts they approached included sixth graders who demonstrate the most popular games at recess in schoolyards with little equipment. A veterinarian sheds light on why Jerusalem has so many fat street cats with shiny coats. The director of Israel Dream Doctors discusses how they reserve a plane seat for a medical clown on every international humanitarian aid and search and rescue mission. Each of these stories reveals a microcosm of how Israel works and sometimes does not function smoothly, but in most cases, the authors succeed in moving beyond more standard start-up nation narratives.

Even though I have taught introductory Israel Studies courses to college students every semester for nearly fourteen years, Israel 201 still contained information I did not know or had failed to consider as a point of departure. For instance, I had not contemplated the politics of Tama 38, the state-sponsored project to reinforce apartments against earthquakes. It not only alters the country’s built environment but also perpetuates unequal property values between the centre and the country’s periphery by leaving the most vulnerable areas, closer to the fault lines, like Tiberias or Eilat, unprotected from nearly inevitable disaster. Nor had I known that there is an Israeli co-parenting site called GoBaby for strangers who want to raise a child together but don’t want to be in a relationship. The children raised through GoBaby receive emotional and financial support, two sets of grandparents, and two stable environments. Topics like these can lead to deeper conversations and an understanding of sociocultural and political trends in Israel.

While the book is mostly 201, some 101-style information necessarily creeps in. For example, it outlines streams of Zionism, the history of the revival of the Hebrew language, of the emotional cycle of Israel’s national days of mourning from Yom HaShoah and Yom HaZikaron culminating in the celebration of Yom Haatzmaut. But I have yet to see other books condense these histories in such a lively, clear, accessible, and gritty way. The authors are unafraid to cheer Israel on but are bold in issuing warnings about what tragically fails, like high rates of traffic accident fatalities or lack of proper psychosocial support for lone soldiers.

Notably, both authors are stand-up comedians and are at ease using humour gracefully and appropriately as they weave in and out of more and less serious topics. They also offer engaging formats to help readers absorb cultural norms. For instance, they include a multiple choice pre-test, ‘How Israeli are you?’ (e.g., You’re a father attending your thirteen-year-old son’s bar mitzvah. You wear:…). Sabra Bingo helps readers to document common sightings and experiences (Bingo squares include ‘Total stranger gives you unsolicited advice;’ ‘Car parked on sidewalk’). Another section provides 75 olim answers to the rite-of-passage question, ‘I knew I was Israeli when…’ (‘I yelled at a cashier in America, and everyone started backing away from me’). Chasnoff and Lovitt provide an amusing list of easy-to-make Hebrew errors, a glossary of key terms, and the most common army slang. I realised how valuable these entertaining formats would be in cultural anthropology texts that introduce a national context in a relatable way.

In speaking of perspectives on teaching and learning about national culture, which this book does well, I do consider one framing problematic: the romanticised and perhaps oversimplified idea of the ‘national psyche’ shaped by a single Jewish history. The notion of a national psyche is too shared, and I’m certain Israel has no common consciousness. The problem of this thinking it that it slides into a monolithic, static, mythical ‘we’. This critique is valid at any point in history but particularly poignant beneath the shadow of the most significant political upheaval Israel has seen since its founding following the judicial reform crisis, evidence there is no shared psyche. I wonder how Chasnoff and Lovitt would address this chaotic moment in their characteristically transparent and humorous way to both novices and experts in a new era.