Israel faces a fateful decision. What should be the final status of the West Bank (Judea and Samaria in Israeli parlance and the Occupied Palestinian Territories in Arab parlance)? The most realistic demographic projections predict that the Arab population of the combined area of Israel and the West Bank will eventually surpass the Jewish population – perhaps even in the not-too-distant future – if the Jewish state retains permanent control over all of the historical ‘Land of Israel’, bringing an end to the country as a Jewish and democratic state. Even the most optimistic demographic projections predict that the Arab population will comprise more than one-third of the country’s total population if Israel retains control over the entire West Bank, not only putting in serious jeopardy the country’s existing character but also likely condemning it to a permanent condition of de facto civil war.

The best option to solve the predicament, of course, would be to reach a negotiated ‘two-state solution’ with the Palestinians, one that leaves Israel intact as a Jewish and democratic state, as well as meets the country’s minimal national security requirements, while providing the Palestinians with a viable country of their own. Unfortunately, such a solution does not seem to be on the horizon, mainly as a result of long-standing Palestinian ideological rejection of the idea of a Jewish state and Palestinian domestic political chaos, though a combination of ideological rigidity on the Israeli right and certain provocative policies by Israeli governments over the years have caused problems as well. Israel, therefore, seemingly has only two feasible options moving forwards: to absorb the West Bank, gradually or otherwise, accepting the existential consequences resulting from such a policy choice, or to take unilateral steps there in order to halt the unmistakable drift towards a disastrous ‘one-state solution’.

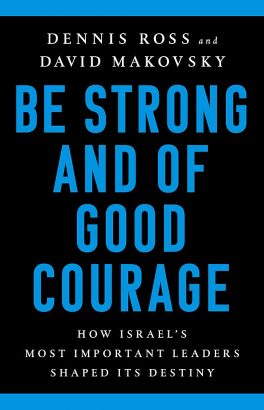

In this outstanding work on the monumental decisions made by past Israeli statesmen, David Makovsky and Dennis Ross call for resolute leadership to stave off the nightmare of the one-state solution. The authors, both of them counted among the foremost experts in the world on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and each of them with intimate experience of the conflict (and its associated peace negotiations) due to their service in the United States government, furnish four in-depth case studies of Israeli decision-making in which the creation or preservation of a Jewish and democratic state took precedence over the quest to reclaim all of the Land of Israel.

The four case studies include Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s decision to accept a partition of the land as the basis of a Jewish and democratic state; Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s decision to recognise, at least in principle, the existence of national Palestinian political rights in the West Bank and Gaza as part of the price to be paid for the peace treaty with Egypt; Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s decision to enter into the Oslo Accords with the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) to repartition the land in order to protect the Jewish and democratic nature of Israel; and Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s decision to withdraw unilaterally from Gaza for the same reason.

In a series of elegantly written, clearly structured and concisely argued chapters, Ross and Makovsky demonstrate convincingly that, whatever his personal experiences, political inclinations and ideological background, each of the four ultimately opted to prioritise Jewish statehood over Jewish rights to all of the land, knowing full well that his decision would not only be loudly contested by significant parts of the Israeli populace but also that it would not necessarily be in his own best political interest. The will to do what was essential for the country rather than what was most expedient for themselves, assert the authors, marks Ben-Gurion, Begin, Rabin and Sharon as Israel’s premier statesmen.

In a final chapter, the authors lay out why and how a future Israeli statesman – whom they fervently hope will appear on the scene sooner rather than later and whom they believe is someone other than Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu – must take action to prevent the continued slide towards a one-state solution. Ross and Makovsky are under no illusion that unilateral Israeli steps – for example, halting all settlement activity outside of the major settlement blocs in the vicinity of Jerusalem and eschewing most territorial claims to the West Bank beyond these blocs – alone will suddenly bring round the Palestinian Authority (PA) to negotiate a comprehensive, just and permanent solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Rather, the authors believe that such steps constitute the best option for Israel under the prevailing circumstances. Furthermore, Ross and Makovsky contend that the United States has a major role to play in making it palatable for an Israeli statesman to initiate such steps.

Be Strong and of Good Courage was published a mere five months before the issuance of the Trump administration’s ‘Deal of the Century’; naturally, then, the authors’ initial reaction to this peace plan is of interest here. And their reaction has been decidedly mixed. On the one hand, they applaud the unequivocal endorsement of a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and they believe that the economic provisions of the plan could improve the atmosphere in the region, possibly sparking a renewal of a peace process that has been frozen for years. On the other hand, however, they believe that some of the territorial (and other) provisions of the plan, if implemented unilaterally by Israel, would seriously undermine the prospect of achieving a two-state solution. Most observers of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict would likely agree with this mixed assessment.

Ross and Makovsky, in sum, have penned an important book that should be given especially close consideration in Israeli and American foreign policy-making circles, particularly among those circles that may disagree with its general perspective. Even those people with no particular stake in Israel’s future, though, will find much of interest in this work, as the authors’ case studies are filled with fascinating and valuable historical information about the prime ministers in question, as well as about the Arab–Israeli conflict itself.