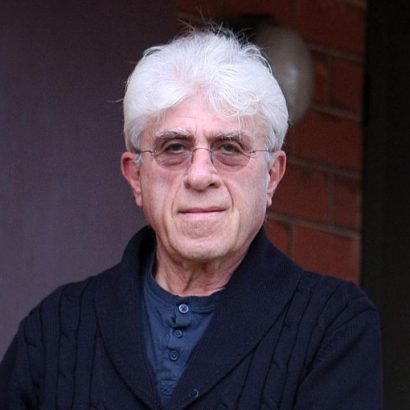

Australian journalist Michael Gawenda reflects on tensions on the Australian Jewish left through the prism of 7 October. Recalling his days as a teenager in Bundist circles, Gawenda wonders of his former comrades: ‘What would they think about my conclusion that the Holocaust had proven the Bundist ideology… tragically mistaken?… What would they think of my growing interest in Judaism? My love of Israel? And how out of that love came my conviction that the establishment of the state of Israel changed what it meant to be a Jew, even for anti-Zionist Jews like I had once been?’. Gawenda is an Australian journalist and was editor of The Age from 1997 to 2004. He is the author of the acclaimed memoir My Life as A Jew (2023).

Two days before the 7 October Hamas pogrom in southern Israel, more than a hundred people crowded into an inner-city Melbourne bookshop for the launch of my book, My Life as A Jew. The bookshop owner was surprised and delighted. My publisher could not stop smiling. The mood was festive.

The Bashevis Singers, a Yiddish band that is well known not just in Australia but in North America as well, performed three songs. I wrote the lyrics for one of the songs and my son the music. The song is about memory, and it is about di goldene keit—the golden chain—that binds Jews to each other over generations, over centuries, over millennia. The Bashevis Singers are my daughter, my son and my great nephew.

Some of the people at the book launch were old comrades from SKIF the youth movement of the Bund, a major force in pre-war East European Jewish life, especially in Poland and Russia, that was virtually wiped out by the Holocaust. Its members were working class Jews, militantly secular, passionate about Yiddish language and culture, socialist and anti-Zionist—by which I mean anti-nationalist— but committed to Jewish peoplehood. For SKIF and the Bund, Jews were a people of the world.

The Bund was finished everywhere—in Eastern Europe, in the US, in Canada—except, strangely enough, in Australia, where in Melbourne in the early 1950s, a group of Holocaust survivors resurrected the Bund and Skif in a place that was as far away from Eastern Europe as one could possibly get.

I grew up in SKIF. It was where I was educated. By the time I was a teenager, I was a dedicated socialist and anti-Zionist, though anti-Zionism back then was worlds away, a universe away, from the antizionism of today. The Bund and Skif were—and remain— tiny organisations shunned by most Jews in a community full of Holocaust survivors for whom Israel was a miracle, gave their life something approaching hope, after the horrors of what they had been through.

On 5 October, at my book launch, I wondered why they had come, some of my old SKIF comrades. What, I wondered, as they came up to the table where I was signing books, did they expect to find in my book? What would they think about my conclusion that the Holocaust had proven the Bundist ideology—the idea that Jews were a people of the world and had no need for a state of their own—tragically mistaken? Fatally mistaken for so many of its followers. What would they think of my growing interest in Judaism? My love of Israel? And how out of that love came my conviction that the establishment of the state of Israel changed what it meant to be a Jew, even for anti-Zionist Jews like I had once been?

What would they think of my despair and anger with a growing part of the left for whom any support of Israel, even for its existence, made you a supporter of a racist, colonialist apartheid state? A supporter of an evil ideology, a Zionist!

There were quite a few journalists at the book launch, among them old colleagues from The Age, the Melbourne daily broadsheet I had edited for more than seven years. I wondered how they would react to my excoriation of journalists—some of whom were old friends and colleagues— who in 2021, had signed a group letter demanding preferential coverage for `Palestinian voices’ over the tired old voices of the ‘Israel Lobby’ and for the right of journalists to be activists for the Palestinian cause?

But on this night of celebration, with the Bashevis Singers serenading me—at least that’s how I felt—these questions and anxieties were not overwhelming. I hoped I had written an honest book. I hoped it would resonate with some people on the left including some of my old SKIF comrades who had not yet concluded that Zionism was a form of racism, and that Israel was the bastard child of an evil ideology.

I hoped too that younger Jews would find it interesting, perhaps even clarifying because what it meant to be a Jew—if it meant much at all— in the second decade of the 21st century in the diaspora was not clear, not for secular, left-wing, and increasingly assimilated Jews.

On Saturday morning 7 October, at 10.00am in Melbourne, I was interviewed about my book on Radio National, the ABC’s national radio network. It was a lively—and sometimes confronting— interview. At the end, the producer played Far Dir A lid. There was applause from the production staff. It had gone well, I thought. At 11.00 am, as I left the recording studio, it was 3.00am in Israel. The beginning of the Hamas attacks on the villages and kibbutzes in southern Israel and at the rave music festival was little more than three hours away.

The world changed in those hours and days after the Hamas invasion. I remember the first call I made to my family in Israel. They are Israeli born, the children and grandchildren of my mother’s brother and her sisters who went to Israel from the DP camp in Austria where I was born.

My family managed to obtain visas for Australia because my father had cousins in Melbourne and Sydney who sponsored us. My mother’s family could not get visas for anywhere. And so, they went to Israel weeks before Ben Gurion declared the birth of the state. Some of them fought in the 1948 war.

We talked for hours that first night of the attacks, all through the night in Australia. And for weeks afterwards, we talked and sent messages and photographs to each other every night. This nightly contact with my family in Israel is just one of the many ways my life changed on 7 October. Before that, we were in contact every now and then. My wife and I visited with them when we were in Israel. My son stayed with them when he visited Israel. But there was nothing like the intensity of our relationships post 7 October.

This was true for many Australian Jews. There are 100,000 Jews in Australia according to the last census. There are probably thousands more because some Jews, secular Jews in particular, answered the religion question on the census form with the word `none’. Whatever the actual number, it is a small community, perhaps a fifth the size of the Muslim community.

But it is a unique diaspora community. From around 1947 to 1952, Australia took in more Holocaust survivors as a proportion of its population than any other country bar Israel. More than the United States, more than Canada. The children of these survivors and their grandchildren form more than half the community in Australia.

The survivors were a remarkable lot of Jews. They rebuilt their lives in Australia, they built successful businesses and academic careers and helped build medical research institutes and renowned law firms. They joined the major political parties. They set up Jewish cultural and religious institutions. They built a Jewish school network unmatched anywhere in the world. More than 60 per cent of Australian Jewish children go to a Jewish day school.

And they were, from the start, fervent Zionists who believed that without the miraculous birth of Israel, so soon after the darkest chapter of Jewish history, there would have been no future for them or the Jewish people. Australian Jews have visited Israel in greater numbers proportionately than the Jews of the United States. And many, like me, have family in Israel, most likely family members who have made Aliya. There are many thousands of Australians who are dual Australian and Israeli citizens.

My book, My Life as a Jew, describes my long journey into the mainstream of the Australian Jewish community and away from its periphery where I was raised and educated.

It describes how I came to feel that a growing part of the left—including former comrades of mine from SKIF, people I grew up with and who were my friends—had come to believe that the only good Jew, the only Jew who can really be a Jew of the left, was a Jew who repudiated Zionism and Israel, its evil creation. I was a bad Jew. Friendships ended, some quietly, some abruptly and publicly, like my friendship with my publisher. We had been friends for three decades. Our parents were Holocaust survivors. We loved Yiddish and Yiddish literature even though she could only read Yiddish writers in translation. My Life As A Jew started out as a letter to my friend, a sort of farewell I suppose. We were different Jews, so different that we no longer could relate to each other. I never sent the letter, Instead I wrote the book.

This friendship’s end is not at the heart of my book. At its heart are these questions: Do I believe in Jewish continuity which is another way of saying do I believe in Jewish peoplehood and if I do, could the sort of Jewishness in which I was raised—secular, universalist, on the left and culturally Jewish, in love for instance as in my case, with Yiddish and Yiddish literature and music—survive more than a generation or two before it disappeared through assimilation and inter-marriage and acculturation? Would my grandchildren be Jews? Did it matter to me? It was these questions that I first began to ask myself when my children were born, that were the ultimate inspiration for my book.

7 October did not render these questions irrelevant but rather made them more urgent. The Hamas pogrom and its aftermath—the explosion of antisemitism and Jew hatred in Australia and North America and Britain and in much of Europe and even in Japan and China where Jews were an abstraction—reminded Jews like me that in Jewish history, what may have seemed to be a golden age for Jews can end suddenly, violently, inexplicably, and with devastating and sometimes murderous consequences.

In 2021, I published a book called The Powerbroker, an Australian Jewish Life. It was a biography of the Jewish Zionist leader Mark Liebler and in a sense, it was the story of a small but successful—and even powerful- Jewish community, one which could produce an internationally recognised and influential leader like Leibler. He was the senior partner in one of Australia’s major law firms who over the years, had the ear of every Australian prime Minister for almost half a century.

When I wrote that book, I did think the Jews were a success story in Australia, in what many had come to consider a goldene medineh—a golden land—for Jews. And they were powerful, not for nefarious reasons, but because the Jewish community had outstanding businesspeople and outstanding lawyers and judges and medical researchers and educators and even politicians.

Everything that has happened since 7 October has shown that the Jews are not powerful, not in Australia and not in the UK and not in Europe and not even in North America where most diaspora Jews live. In the main, they are small, politically powerless communities which makes them politically marginal. At best. There are five times the number of Muslim Australians as there are Jewish Australians. Muslims far out numbering Jews is the reality in Europe and in Britain too. Diaspora Jews are not powerful politically and that is especially true on the political left.

The Labor Government in Australia has been all over the place on Israel and the Palestinians and on the Hamas-Israel war. There are vital Labor-held seats in Sydney and Melbourne that have significant numbers of Muslim Australians, enough to swing election results. The pro-Palestinian marches of tens if not hundreds of thousands of people, the flood of pro-Palestinian support on social media, the increasing hostility towards Israel and Jews because of what is happening in Gaza has meant that from the Prime Minister Anthony Albanese down, there has been a failure to properly, unequivocally, call out what has clearly been an explosion of Jew hatred in Australia. They cannot condemn antisemitism without at the same time, condemning Islamophobia when they surely know that there is no equivalence—nothing like the same consequences— between the two. When they must know that all this does is make Australian Jews feel unsafe, unprotected, unloved.

Do I believe in Jewish continuity, in Jewish peoplehood? If I do, what does that mean for me and for Jews in general and for Jews like me in particular? These were urgent questions before 7 October and they are even more urgent in this post-7 October time when neither Israel nor the Jews of the diaspora can go back to what was before. It is more urgent than ever to ask, as my book does, what it means—beyond being part of a centuries long, often violently, murderously persecuted minority—to be a Jew. If we are Jews only because of our history of victimhood—I believe we are doomed.

My Life As a Jew

Published by Scribe UK

Books can be purchased through Scribe UK