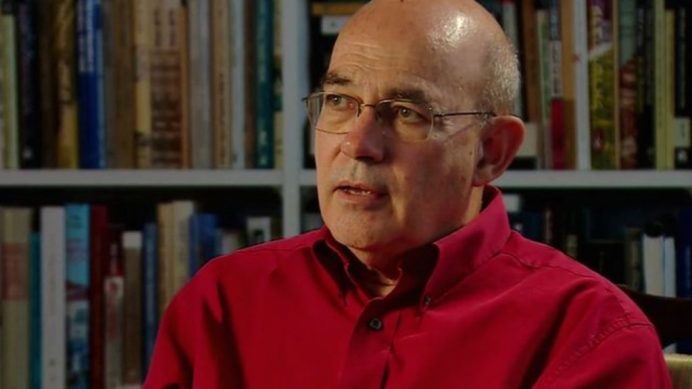

The Israeli historian Tom Segev’s books One Palestine Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate (2000) and A State at Any Cost: The Life of David Ben-Gurion (2018) have attracted critical acclaim, controversy and wide readerships in equal measure. In this wide-ranging interview that kicks off Fathom’s Mandate100 series, BICOM CEO James Sorene talks to Segev about the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion and the craft of combining journalism and history.

Part 1: The British Question

James Sorene: Let’s start off with a big question. Did the Mandate period provide the foundations for Israel or did it hinder the Jewish people from fulfilling their goal of an independent state?

Tom Segev: When something goes wrong Israelis sometimes say, ‘Let’s bring the mandate back!’ The further we get from those years, the more Israelis realise that the Mandate period contributed significantly to the creation of the State of Israel. It was under the auspices of the British Mandate that the Zionist movement was able to bring in hundreds of thousands of Jews and lay the political, economic, social, military and, most importantly, cultural infrastructure necessary for Israel to exist. The bottom line is that Israel owes much of its existence to the British. It’s not as if everything started in 1948; rather, 30 years of the Zionist project had already occurred under British rule.

The British were neither pro-Jewish nor pro-Arab; they were simply pro-British, and they said so. Sometimes this manifested positively for Jews and other times negatively. In a way, the British loathed both peoples, thinking neither was worth the life of one British officer.

JS: You say at the start of your book that the ‘British seemed to have lost their bearings in this adventure’. How so?

TS: I do not want to insult any historian in particular, but most historical studies concerned with the Mandate tend to present the period in rational terms. We have been taught that Britain had certain strategic interests in the Middle East, such as defending the Suez Canal, protecting its trade routes to India and utilising Middle Eastern oil. However, one of the most striking discoveries for me when researching this period was that the Balfour Declaration in 1917 and, to a great extent wider British policy in Palestine afterwards, was irrational. The British archives at Kew hold letters, reports and position papers, written mostly by army chiefs in Egypt, warning the government in London to stay out of Palestine. The government clearly had other ideas and decided that it wanted the League of Nations mandate to govern Palestine.

JS: Why did Britain support the Zionists and not the stronger Arab side?

TS: The explanation is simple: the British believed the Zionists were the stronger side. That belief was based on a combination of philosemitic and antisemitic feelings. The British were pro-Jewish in the sense that they were Christian Zionists, but at the same time, the British believed that Jews controlled the world, the media and the banking system. For instance, the British believed the Jews would be decisive in determining whether or not the US would enter World War One.

How do we know this? Late in 1936 former Prime Minister David Lloyd George published his memoirs, at a time when many were having doubts about the feasibility of the Balfour Declaration. Lloyd George felt the need to defend it, and his major defence was that the British needed the Jews as allies in the war against Germany and the Ottoman Empire. By 1936, anyone with a basic grasp of reality understood that the Jews did not in fact ‘run the world’, so this reflects the antisemitic trope of the ‘all-powerful Jewish people’. It also reflects how accessible officials and major players within the British government were for Zionists. The British government treated the leading Zionist figures as if they were very important elements in world history.

In time, Palestine became a very heavy burden to bear for the British. As early as 1937, the British government offered partition, which was a sign that it ‘wanted out’ because Palestine had become an uncontrollable land. When World War Two broke out the British realised that relinquishing the land was not wise, but when the war ended, they knew the days of the Empire were numbered. When the British gave up India, it was only a matter of time before people would ask whether Britain should hold onto Palestine. We have a debate in Israel that asks, ‘Who kicked the British out of Palestine?’ Was it the Labour movement, the revisionists, the nationalist-right etc.? In reality, the British decided themselves to go because the time of their adventure ruling distant pieces of land was over.

JS: How well did Britain govern Palestine?

TS: It is amazing how many administrative addresses I found – the Mandate was governed by the prime minister, the colonial office, the RAF and the Mandate Administration amongst others. Each institution had a different view about how Palestine should be governed. Until the end, there were some figures that were religiously pro-Zionist, whilst others were antisemites. But as I said, most British figures were simply pro-British. They were not ‘pro’ anything else. This majority insisted on getting out of Palestine by 1937 regardless of what the Balfour Declaration initially said. This then took 10 more years, and World War Two and the Holocaust interceded. But through this traumatic decade, the British came back to this fundamental idea: that partition was inevitable.

A British Betrayal?

JS: Let’s talk about the ‘betrayal argument’? The British refused further mass Jewish migration to Palestine in the 1930s, and some historians have argued this was a betrayal of Britain’s earlier promise in the Balfour Declaration to help facilitate the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine. Do you find that argument persuasive?

TS: In the 1920s, limitations on migration were organised by the British in collaboration with Zionist organisations. The level of migration was based on the economic capacity of Palestine. But by 1939, the British worked out that they needed Arab support in the upcoming war. They knew that the Jews would be forced to support them anyway because of the forces Britain was fighting. The Arabs were supporting the Nazis, so Britain identified the need to make overtures to the Arabs to win their support. It was very calculated. How many Jews would have survived the war had Palestine remained open past 1939? I cannot answer hypothetical questions such as these.

Britain decided 75,000 Jews could come, but this number was never reached. This was not because Britain prevented Jews from arriving, but because the context of war made it impossible for many Jews to arrive. Ben-Gurion used to say that had the partition plan had been implemented in 1937 and the State of Israel come into existence then, it would have ‘saved the Jews’. This idea is understandable from the point of view of Ben-Gurion as a ‘politician’, but it is nonsense. Everyone knew the way to save the Jews was to defeat Nazi Germany, and the millions of lives lost in order to achieve that goal demonstrates it was not an easy task. The tiny little Jewish state would not have defeated Germany and bought Israel into the present day, of course not.

But this argument needs to be understood in terms of the psychological trauma of the Holocaust, and the absolute helplessness of the Zionist movement in preventing it. This is the great tragedy. People say that Israel was a result of the Holocaust. In fact, there was no greater blow to the Zionist dream than the Holocaust. And that is also something that Ben-Gurion understood: that the Holocaust was also a crime against the State of Israel.

In some ways, there is a certain sense of betrayal. In the two and a half years following World War Two Britain did try to prevent immigration to Palestine, but it was ineffective and many Holocaust survivors were able to migrate there. Therefore, I do not think that it is either meaningful or significant that the British changed, or went back on, their partition policy.

Part 2: Putting the Mandate in Perspective

JS: How did writing One Palestine Complete change your own understanding of the Mandate period?

TS: Well, at school we were taught the anti-colonialist approach to the British Mandate, almost as if we were Palestinian Arabs. We were taught to hate the British from a young age and taught to worship the heroes of the underground terror networks, termed ‘national liberation organisations’ and not ‘terrorists’ by my elders. But when the Israeli state archives provided access to some previously secret documents my immediate reaction after reading them was: ‘Wow, this is not what I learned at school’. This was the experience with many issues that us ‘New Historians’ looked into, including the British Mandate.

I became enchanted by the period. After all, when was the last time Jews and Arabs lived in peace on the same land at the same time? The Mandate was a colourful period, during which people from all over the world built a new life and a new society. The Hebrew University was opened, factories started to produce metal goods and Alice in Wonderland was translated into Hebrew. All of this made all the more remarkable by the lack of government intervention. It all happened under a very weak administration and almost no central laws: practices were created and adhered to by local communities. In this sense I see the period as unique and attractive.

Part 3: David Ben-Gurion and Biography

JS: What made you decide to write a biography of David Ben-Gurion?

TS: Lots of new material has been opened to the public. The Cabinet papers from Ben-Gurion’s time as prime minister are fascinating because ministers spoke under the assumption that their conversations would never been made public. We can also learn a lot from Ben-Gurion’s personal diaries, which have been opened for public research. These new sources make it possible to get a multi-dimensional picture of Ben-Gurion and understand what really motivated him. While I was researching the book, four other biographies were published about Ben-Gurion in Israel alone.

Israelis associate Ben-Gurion with statesmanship and vision. Whilst I was working on the book not a single day went by without him being mentioned in the media. There is also a documentary film, based on interviews with Ben-Gurion, that has just been released and the Israeli public are willing to pay for babysitters, pay for parking etc. to visit a cinema and watch it. Ben-Gurion has become incredibly important to Israelis over the years. These were the factors that led me to write a new biography.

JS: The book is quite iconoclastic. Ben-Gurion seems to be left out of many historic decisions early in his career. Later, he is abroad when key events are taking place. His personal life was also very chaotic. He seems a complicated individual. Were you conscious you were bringing out these elements of Ben-Gurion’s character?

TS: This is the story told by the available documents. I cannot pretend that he was a nice man. I was asked many times why I needed to include the affairs that Ben-Gurion had with other women, for example. But look, if a statesman has to make a major political decision and on that same day receives a letter from his wife telling him she will commit suicide because of his affairs with other women, well, that is also part of the story. There is a naivety to his character, a boyish mischief, not always erotic, that I thought it was necessary to point out.

At the core of his character was his commitment to the Zionist ideology, which he demonstrated very early in his life. I once went to interview him, when I was 23 and he was 83, for a weekly journal I wrote for at Hebrew University. I interviewed him for three hours, as he was no longer in office and he had lots of time. One of the things that surprised me was his claim that he was an ardent Zionist at age three. I still have the tape of this conversation, and you hear me ask: ‘Mr Ben-Gurion, this is something you were aware of at the age of three?’, as if I did not believe what he had said. He replied: ‘ Yes, all the children I grew up with were all Zionist by that age!’ I thought this was an odd thing – maybe he was no longer connected with reality. But when I started researching for this biography, I certainly saw his attachment to Zionism from 13 when he began to form Zionist youth clubs and encouraged his neighbours in Poland to speak Hebrew. Zionism for him was everything and everything else he judged in relation to it. He envisioned Zionism along the same lines as Herzl: he wanted a Jewish state in Palestine as soon as possible, incorporating as many Jews and as few Arabs as possible.

Ben-Gurion thought the Jewish state would be built by European workers and middle class Jews. Instead, the Jews of Europe were gone; the Holocaust survivors were weak both psychologically and physically, and Ben-Gurion did not believe he could depend on them. Then, unwillingly but without any other real choices, the Zionist movement discovered the Jews of the Arab countries. Before the Holocaust, no one paid much attention to them. Herzl hardly knew that they existed. Ben-Gurion had reason to be disappointed because everything was turning out to be far more difficult than he had anticipated. Israel did not become a European stronghold in the Middle East. It became a refuge for people who were not prepared for life in a modern country. Ben-Gurion felt that the Holocaust was a crime against the State of Israel, as he had envisaged that state during his childhood.

JS: As you say, Ben-Gurion was wedded to the idea that the Jews of Europe – the workers – would build Israel. Why was he not more pragmatic about the eastern Jews who could help develop the State of Israel?

TS: Zionism is a European movement; everything about Zionism comes from Europe and it belongs in Europe’s history with socialism, nationalism, and secularism. This was the world Ben-Gurion came from; that is his world.

But Ben-Gurion’s Zionism required a state at any cost. I think this is the core of Ben-Gurion’s Zionism and of the State of Israel. So eventually he said, ‘Well, if this is what we have to do to create a Jewish state then so be it’. There’s a page in his diary that reads like it was written by an accountant – he counts people and asks where these people can be found. From Russia we cannot get them, in Europe they are gone and in American they will not join us; it is only after those Jewish communities are ruled out that he begins to look towards Sephardic Jews.

Some Zionists questioned whether Israel needed these people or not. In the end, Ben-Gurion said ‘Yes, we need all who can come to live in Israel, especially in light of the Holocaust.’ And he was fascinated by the Jews of Salonika and the Yemenites, both working peoples he thought could replace Arab workers, especially the Yemenites. He never forgot what these groups did in building the Zionist dream. But their wages were higher than the wages Arab workers would receive, but lower than the wages that Ashkenazi Jewish workers would receive. Often Sephardic Jews were not treated equally, and they were discriminated against. It was a form of racism and it made state-building even more difficult.

JS: Ben-Gurion was able to see things that others perhaps did not see. He arrived at the conclusion that parts of the Jewish population were going to be destroyed ahead of other thinkers, whilst he also predicted that the Zionist movement would need to build up its military capacity very quickly after the Second World War. He was also very good at understanding power politics, such as how America was likely to interact with Israel. Did you discover a figure more visionary than you perhaps anticipated?

TS: Some of these things did not require much vision. For example, Hitler wrote that he was going to destroy the Jewish population: so, what’s the big vision there? The interesting thing about Ben-Gurion is how his time in America shaped his thinking. He was exiled to the US by the Ottoman authorities in 1915 and he spent the rest of World War One living in America. He became a very big admirer of the American political system and its values, and he could be regarded as father of the Americanisation of Israeli society. He introduced American concepts to Israel: mass immigration, a melting pot, pioneering, the Wild West of the Negev. All of these concepts come from America.

After the Second World War Ben-Gurion saw that Israel belonged in the American world. Israeli politics was still debating whether it should ally with the Soviet bloc, given the strong leftist presence in Israel. He decided, rightfully I think, that Israel belonged in America’s orbit. He also believed Israel needed to establish a relationship with Germany. That the country did so was one of his major achievements. He solved the problem of ‘orientation’, as Israeli politicians called it. These are things that he was able to see whilst other Israeli politicians were, for example, still interested in maintaining relations with the British.

On the other hand, Ben-Gurion also believed that the two dwindling imperial powers, Britain and France, would create a new Middle East, as exemplified in the Suez Crisis in 1956. I think that misjudgement challenges the claim that Ben-Gurion was a visionary who knew everything. He also changed his mind a lot. I have been told by other historians that Ben-Gurion wrote millions and millions of words, so you can prove anything you would like regarding Ben-Gurion’s thoughts and actions. Whatever you want to prove, Ben-Gurion will have said or written it once. He constantly documented his life through his diaries. Many who knew him said that if you were sat with him you would never see his face, only his forehead, because he was constantly writing. He was also a great letter writer. There are tens of thousands of Ben-Gurion’s letters, and he kept a copy of each one he sent. He wrote on blue carbon paper in a notebook and then a secretary would type up. As early as the age of 20, when he first arrived in Palestine, he sent letters to his father and told him to keep them because there would be a time when he would want to read them back to himself. Even at this age he knew that he was making history.

There was no limit to his imagination. For instance, he considered receiving French Guinea from France: I do not know what he intended to do with it, but a delegation was set up to travel there and engage with the idea. At one point he suddenly developed an interest in Buddhism and travelled to Burma to study Buddhist teachings. Ben-Gurion could be romantic and poetic. He often had irrational transitions from depression to uncontrollable happiness.

Ben-Gurion was also set apart by his journalistic talent to describe people and events and to see the irony of things. I should add, on the subject of irony, that he had absolutely no sense of humour. That makes it difficult for a biographer!

JS: Do you see continuity or rupture between the 1950s and the present, with regards to the nature of Israeli leadership?

TS: Ben-Gurion was very special. First, he was not corrupt. The only thing he did that was a little unethical was that he used to buy many books at Blackwells in Oxford, funded by the Zionist movement and later the Israeli Government. Ben-Gurion did not stay in fancy hotels, he often travelled by boat sharing a carriage with four people he did not know – he was very modest and usually relied on local people.

Second, he genuinely worked for the realisation of his ideology. From very early on in his life what he says can be placed into an ideological context. By contrast politicians today are often not ideological because they are trying to appeal to everyone. The Israeli people trusted him and believed in Ben-Gurion because he believed in himself and what he was saying. He was very often very controversial, but he was always genuine.

Part 4: The Craft of Storytelling

JS: You are a master craftsman, turning vast amounts of information into eminently readable stories. What is the secret?

TS: A lot of it is scepticism. I need any claim I make to be substantiated and supported with evidence. I am also really committed to the ‘story’. People always say I am a post-Zionist or an anti-Zionist, but I do not have an ideology. I am a very un-ideological person, committed to the ‘storytelling’ first and foremost.

I gave a seminar years ago at the University of Berkeley and I invited the students to examine the notion that the best history is journalistic history and the best journalism is history-informed journalism. I write for readers, not for professors or academics. I have always been a journalist and this combination of history and journalism is, I believe, a good mixture.

Segev writes:”I became enchanted by the period. After all, when was the last time Jews and Arabs lived in peace on the same land at the same time? ”

He ignores the many attacks by Arabs on Jews. Like the 1920 events when the writer Brener was murdered in Jaffa. Or the 1929 Arab riots when 133 Jews were murdered ans more than 300 were wounded.

He has to be reminded that the Zionist movement was the movement of national liberation of the Jewish people. Its aim was the establishment of an independent Jewish state. And when the British tried to diminish the Jewish immigration the Zionists fought against them. That caused the UN to intervene and in the end Israel came into being. The British were against the partition and abstained in the UN partition vote.

Segev is indeed a post-Zionist.

I find this interview disappointing. TS makes some interesting points worth pursuing but the interviewer does not “bite”. For example:

“Ben-Gurion was also set apart by his journalistic talent to describe people and events and to see the irony of things. I should add, on the subject of irony, that he had absolutely no sense of humour. ”

How can one be simultaneously be an ironist and devoid of humour?

The fact that TS recognized Ben Gurion to be a man of Irony is significant if you attach to irony the kind of civilizational standing that Roger Scruton does. Irony, says Scruton, looks “on the spectacle of human folly and wryly show us how to live with it.”

“The ironic temperament [is] a virtue—a disposition aimed at a kind of practical fulfillment and moral success.. a habit of acknowledging the otherness of everything, including oneself. … it is a mode of acceptance rather than a mode of rejection. It also points both ways: through irony, I learn to accept both the other on whom I turn my gaze, and also myself, the one who is gazing. … irony is not free from judgment: it simply recognizes that the one who judges is also judged, and judged by himself.”

How is it possible to be a man who recognizes the irony in human affaires and follies with the ability to articulate these insights in words, while being bereft of humour?

For humour without irony we can go look at der Sturmer caricatures of Jews.

But is there anywhere in human experience irony without humour? Any ironic statement triggers a smile or amusement in the mind at least.

If TS could not understand this aspect of Ben Gurion, could it be that he may have misread other aspects? Perhaps TS did not quite comprehend Ben Gurion as deeply as he thinks he did?