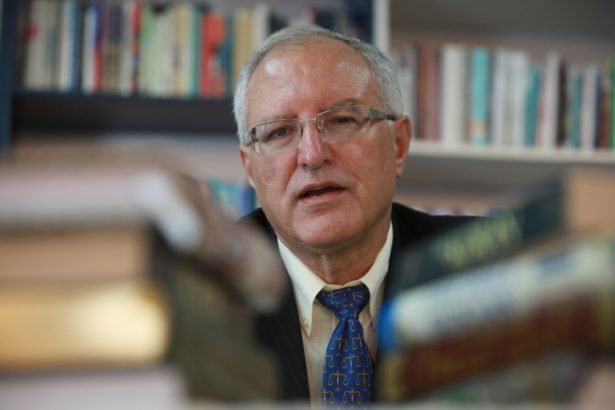

The great grandfather was the custodian of David’s Tomb and Daoudi, in reference to King David, was added to the family name. The great grandson, a Fatah member from 1967 to 1975, a consultant for the Palestinian Authority in the 1990s, is today working to revive the Palestinian peace camp through his organisation Al-Wasatia and his Koranic-inspired philosophy of the middle way. He spoke to Fathom Deputy Editor Sam Nurding about his family history, his political journey and his philosophy of peacebuilding. This is a voice not often heard in the West: ‘Today, when I call for peace with Israel and to recognise Israel, I am a termed a “traitor” while PA officials can call for a one-state solution, support so-called “anti-normalisation” and back boycotts of Israel and be regarded as “national heroes”. This is basically our dilemma.’

The Wasatia Initiative

Samuel Nurding: Why did you create the Wasatia Initiative and what does the term mean?

Mohammed S. Dajani-Daoudi: On a Friday morning during the month of Ramadan back in late 2006 I was standing on the balcony of my apartment overlooking an Israeli checkpoint that separates Jerusalem from the West Bank. Hundreds of West Bank Palestinians were queuing and pushing at the checkpoint to cross and reach Jerusalem to pray at the Haram al-Sharif. The Israeli border police were pushing them back with horses and firing tear gas at them because they did not have permits to cross. I assumed these people were extremists and that the Israeli border police would eventually shoot them, creating a tragic media event. Contrary to my expectation, I noticed that the situation was cooling down. The Israeli officers at the checkpoint offered to transport the crowd via buses to the Haram al-Sharif to pray after being checked and taking their identity cards, and then the buses brought them back to the checkpoint where they retrieved their identity cards and went home.

Having taught a course on Game Theory, this appeared to me to resemble a win-win outcome for both sides. It inspired me to think that we can resolve our protracted conflict by creating a win-win outcome. The question in my mind was, who represent these Palestinians? They were religious because they insisted on praying at the al-Haram on a Friday since they believe it is more blessed. However, they weren’t extremists because they agreed to be taken to the holy site on buses provided by Israelis and then to return peacefully home.

I borrowed the term ‘Wasatia’ from the Quran to avoid using the term ‘moderation’ since it is perceived by Palestinians as a Western import. In the Quran, the second chapter titled Surat al-Baqarah (Cow Surah) is the largest in the Quran and is composed of 286 verses. Verse 142 says, ‘God guides whom He wills to a straight path’. The next verse says: ‘And thus we have made you a just community (created you a moderate/ temperate/ just/ balanced/ middle ground nation’). I adopted that verse in order to reach out to the Muslim community. So far, our message has been well received locally and internationally.

On January 2007, I published the book al-Wasatia (Arabic) to introduce the philosophy of moderation, justice, and balance. Initially, the focus was on moderation within Islam, which I was introduced to by Prince Hassan of Jordan who was a staunch advocate of that concept. I thought of establishing a political party, the Wasatia Party, but I came under attack by both Fatah and Hamas, who accused me of taking money from US intelligence services to ‘Westernise Islam,’ which of course was not true! So, I dropped the political party idea and decided to promote Wasatia as an initiative and a movement to gain ground within the community.

Wasatia and Peacebuilding

SN: Can you describe the philosophy of the Wasatia movement?

MD: I founded the Wasatia Movement to inspire a moderate, peaceful culture based upon the teachings of the holy scriptures and the classic thinkers and philosophers. The goal of the peacebuilding effort is to create a culture of tolerance and reconciliation within the Palestinian community and between the Palestinians and the Israelis. We aim to revive the peace camp in Palestine and Israel. We believe that moderation paves the way for reconciliation in the midst of conflict, reconciliation ushers in negotiations in good will and reciprocal trust, and this would eventually bring peace, democracy, and prosperity: it’s the peace cycle.

SN: You have developed a conflict resolution model called ‘Big Dream, Small Hope’. What does that mean?

MD: Back in the late 1990s I was invited to facilitate between two groups of Israeli and Palestinian religious teachers in Antalya, Turkey. During the first session the groups descended into a shouting match with their maximalist viewpoints and I thought it was hopeless. Then, I remembered a quote by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish and decided to recite it to them: ‘What is more important, a big dream or a small hope?’ They were puzzled and kept asking what I meant. After the tense environment cooled, I explained, ‘The big dream for Israelis is to wake up one morning to find that Palestinians have been vanquished and they have Jerusalem as their un-contested capital where they would build their Holy Temple.’ The Palestinians envision the same dream. The moral dilemma here is that there are millions of Israelis and millions of Palestinians living on the land and they are all very much attached to it. For the big dream to materialise, one side must wipe the other off the map.

The ‘small hope’ for both sides is to wake up one morning to and realise they can coexist in harmony, security, and peace – it does not matter in one-state, two-states or any federal arrangement – enjoying prosperity, hope, and trust.

I presented this conflict resolution model in talks to many universities in Europe, the US and Israel. I found that groups and individuals in conflict are fixated on their narrative of history, to serve their political agenda. They do not recognise the other, they dehumanise, demonise and delegitimise their enemies and have their historical maps ready in hand to show their legitimate claim to demand the repossession of what they consider their historic homeland. I faced this dilemma not only in Palestine and Israel but also in conflict areas such as Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.

SN: Is there a silent majority for peace in Palestinian society?

MD: Before 2006, I thought that a majority of Palestinians were religious extremists, had maximalist demands and viewed the victory of Hamas in the January 2006 elections as a clear indication of that hard-line attitude. However, my work in peacebuilding showed me a different picture. A majority of Palestinians want to coexist with the ‘Other’ in peace but do not believe the Israelis want peace. Thus, they worry that their very existence as a people, and as a culture, is threatened by the settlers. They avoid expressing moderate views for fear they be accused of being traitors or collaborators. This fear is reinforced by the asymmetry of power between the two sides. The huge Israeli advantage has not been used to settle the conflict in a just and conciliatory manner or to convince the Palestinians of their peaceful intentions.

SN: You wrote an article in which you disagreed with describing Israel as an ‘Apartheid State’. Why?

MD: It is not a true comparison. The Israeli legal system does not enforce racism. Moreover, the description stops us seeing the elephant in the room, namely, the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories. The goal of the Palestinians is not equal rights under occupation but to end their humiliation, misery, and suffering under the harsh and repressive occupation.

To achieve peace, Palestinians and Israelis should humanise the image of the other in his/her mind and build bridges of communication, bolstered by soft dialogue. It is a contradiction to say you want peace with Israelis whilst at the same time saying you are boycotting them. We do not want a peace based on a piece of paper, but a peace supported by the people.

Family Roots

SN: Can we talk about your journey to these ideas? Let’s begin with your family history, which is fascinating.

MD: Sure. The family name is double-barrelled, Dajani-Daoudi. The ‘Dajani’ refers to my great grandfather, Sheikh Mohammed Dajani, who came to Jerusalem from Morocco, where he had a mosque and taught people about Sufism. It is believed within the family that he dreamt one night that the Prophet David came to him to ask if he would go to Jerusalem and clean his tomb, which at the time was being used as a dump site. So, my great grandfather walked from Morocco to the tomb and cleaned the area, and then he decides to start teaching pilgrims who visit the tomb about Sufism, Islam, and cooperation with different sects. The Sultan, who was trying to build a wall around Jerusalem at the time, the city being continually ransacked by different tribes, appointed my great grandfather to be the custodian of David’s Tomb. He was the only person allowed to take food from the Kiya, a place where people would go and eat for free, to David’s Tomb and he would feed the pilgrims. And thus, Daoudi, in reference to King David, was added to our name.

Up until 1948 the area around David’s Tomb belonged to my family; after the war the area fell into the no-man’s land that divided the armistice lines between the newly established Israel and Jordan, but it came under Israeli control. There were over 40 members of the Dajani-Daoudi family living there. My grandfather and his brothers had a lot of business in Egypt and Syria. My grandfather even visited London once and my father became the sole agent for more than 50 British products. By the 1960s my family were selling all sorts of British goods in Jerusalem.

When the violence started in Jerusalem in 1946-47 my grandfather decided to send his wife’s side of the family to Egypt, where his brother had started a business. When the Jewish forces took over West Jerusalem from the British, he was forced to leave the area. A neighbour once told me that she saw my grandfather leaving his house and asked him to bring her back some meat from the souq. My grandfather told her that he had meat in his fridge which she could have, and she said to me that when he went to attend his businesses, he never came home. Later, my grandfather told me the story of his departure. He said that after he was sent to East Jerusalem, he asked a British officer, who was a close friend, to go back to his home in West Jerusalem and collect all the jewellery and money he had kept in the safe. He never saw the British officer again.

After the 1948 war my grandfather found a house next to the Old City and he asked his family to return from Egypt. He arranged to bring generators to the Old City as it lacked electricity. Soon after, he started to supply and charge the Old City and its surrounding areas. This business would later develop into the Jerusalem Electric Company. My grandfather was self-reliant. He used to say, ‘nothing scratches your back like your fingers’. In the early days of Israeli control my grandparents had very little, so my grandmother registered herself and the family as refugees – to get monthly free food and clothes. But when she went home and told my grandfather what she had managed to get for the family, he told her to take the clothes and food back and tore up the refugee cards. That was the lesson our grandfather taught us. Being a refugee was a state of mind. You do not want to be dependent on others, because then you’ll be dependent all your life. Instead, you want to be independent and free.

Business

My grandfather never talked about his wealth. One friend of his told me that people used to say of our family, ‘They have wealth that the fire cannot extinguish.’ In 1949 my grandfather rented a rundown building near Jaffa Gate from the Patriarch Church, which he turned into a hotel, renovating the building and buying new furniture and carpets from Syria. The problem was that Jaffa Gate was at one end of Jerusalem, and in-between West Jerusalem and the hotel was no-man’s land, which was shut off to the public. Along the walls of the city were the Jordanian army and the citadel was used by the Jordanian army as its headquarters, so not many people could access the hotel.

To overcome this obstacle, my grandfather convinced the Chamber of Commerce and the municipality, which the hotel hosted, to use Jordanian and USAID money to build a road connecting the outside of the city to Jaffa Gate. The new road placed the hotel at the centre of East Jerusalem rather than at the periphery and it became one of the best in the area.

Another business my grandfather started was a meat house and he supplied many residents of Jerusalem. He also ran hospitality at the Jerusalem airport. I remember as a young boy I would go to the airport and sell stamps to people returning home who had loose change they no longer needed.

My grandfather was talented in business but his views were not in synch with the Jordanian state so he was never fully trusted. He believed that there should be an independent Palestinian state, but he was not interested in a career in politics. He had a lot of friends from different places, Egyptians, Syrians, Jordanians, and my father and I learnt how important that is from him. For example, before 1948 the Dajani family ran a football team and Jews and Christians played for us. In 1967, when Israel took over the hotel from my family, my father was able to be reconnected with friends he knew before, some of whom had become generals or ministers in the State of Israel, and was able to regain the hotel from the army, who wanted it but relinquished it and went to the citadel instead.

I carry my grandfather’s name. My grandmother visited my mother when I was born and she named me Shihad, which they wrote on the birth certificate. When my grandfather came and visited soon after he asked what they had called me, and he said in response, ‘Why? He is my grandson and he should have my name.’ So that night he called the doctors and they added Mohammed to my birth certificate.

Growing up in Palestine

SN: In what ways did your upbringing shape the political positions you have today.

MD: I attended the Quaker School in Ramallah, and this style of teaching taught me tolerance. The dean studied at Al-Azhar in Egypt – although he was a Christian, he got accepted because his name was Farid and they assumed he was a Muslim – and he taught Arabic like a story with people and ideas. The principal of the school was an American, so a lot of Western culture was incorporated in the teaching. I remember during assembly the dean used to read from the Bible, Koran or the Old Testament and we would not know the difference. We grew up never to discriminate. The school was also very apolitical. We would often watch through the windows of the school the local population protesting against the Jordanian system or in support of Egyptian President Nasser, and they used to ask them us to join but we didn’t feel like we belonged there so we stayed away.

At the time I was living in Jerusalem and would commute each day to school. I remember one day being on the bus and someone shouting that US President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated, and to me it was a massive shock because he was my hero. But by the time I got to the American University in Beirut, Kennedy was regarded not as a hero but as the enemy, and so my idols changed. But in school we loved American culture, watched many American movies and we used to play music, or tennis, which wasn’t available for other children in the West Bank.

The Six-Day War

SN: How did the Six-Day War impact on you?

MD: When the war broke out the university closed. We listened to the radio and counted how many Israeli tanks or planes the Arab countries were blowing up. Only later did we realise that the information they were giving us was all a lie. The Arab Baathist parties brought buses to the university and asked us to join in the fighting, and so I jumped in. They took us first to the Lebanese mountains, where the head of the PLO had built a huge villa, and they taught us how to shoot and plant mines in just one day. We were then sent to Syria and supplied with Chinese rifles and each soldier was given six bullets. I remember people treating the guns like toys and firing shots accidentally on buses taking us to the front line in Jordan. When we arrived the army wanted us to cross the Jordan River but it was the fifth day and wounded soldiers were already returning, saying the war was over. We were all shocked.

When my father heard that Jerusalem had fallen to Israel, he left his house in Jericho and went to Amman, to my aunt’s house. I soon arrived and although they were very happy to see me, I told them they shouldn’t have left their home in Jericho. Whilst in Amman my father became extremely depressed and attempted suicide by driving his car off a cliff. My brother came from Jerusalem to see him and he walked back to Jericho with our father – the border was not officially closed but soldiers were shooting at people trying to cross back into the West Bank. In Jericho one of my cousins had a plantation. One day the Israeli army turned up because one of the soldiers was a Dajani, who had married a Jew, and he had come to see his relatives on the plantation. He gave my father a jeep and accompanied him to Jerusalem.

SN: How did the war change your views about Jews, Israel and America?

MD: After the 1967 war I went back to the American University in Beirut and I joined Fatah. I remained a member until 1975. I had become radicalised in the environment of growing Arab nationalism in Lebanon at that time. We were taught that Israel is the enemy: an imperialist country, a dagger in the Arab world, and a puppet of the US. Despite the fact that I was studying at the American University in Beirut this is what I was told, which now I see as a little ironic. Yet I believed it. I was the first student ever to speak at the graduation ceremony – after being head of the Student Union – and in my speech I refused to accept my degree on the basis that it represented imperialism and in solidarity to many of the students who weren’t allowed to receive their degree because they could not fulfil their financial obligations.

After witnessing a lot of corruption and misuse of funds in Fatah, and losing hope in the Fatah cause, I decided to register at Loughborough University to do my PhD. However, I only stayed a few months. I was supposed to be the Fatah representative to London but by this time I wanted to leave politics. I went to the US to study because I was not allowed to return to Jordan or Syria due to my Fatah affiliation. I gained my PhD and started teaching in South Carolina. My brother, who was doing his PhD in Houston, Texas invited me there, where I completed another PhD.

Back to Jordan and Jerusalem

In 1985 my father managed to get me a pardon from the King of Jordan that allowed me to return (I was still unable to return to Israel), so I began teaching in the political science department at the university there. In 1993 my father arranged for my return to Israel on the family reunification scheme because he was diagnosed with cancer. It was only the second time I had set foot in Jerusalem since the 1967 war. The first time was in 1968 to collect my Palestinian ID card.

In the beginning it was extremely difficult for me to settle. Even in the US it was hard for me to speak to Jews, or at least to distinguish between Jews and Israelis. I was teaching in the same department as a Jew teaching Hebrew, but in the four years we were there we didn’t speak once.

Working for the Palestinian National Authority

When the Palestinian National Authority (PA) was established in 1995 I joined the UN Development Programme and was put in charge of setting up the PA ministries and the training centres for the new Palestinians civil servants. I ran an institute based in Gaza and the West Bank and trained more than 20,000 people in everything from accountability to management. I left the UNDP after two years and joined the PA as a consultant at the Ministry of Planning, and then became the Director of Technical Assistance and Training. We had a $21m trust fund from the World Bank to perform sectoral studies for the Palestinian economy. We had more than 50 reports written up by many different corporations. For example, an American company wrote a report on how to build our tourism industry. Our thinking at the time was that we are preparing the ground for two states and therefore we need to build our own institutions, and the reports were evidence of our strategy to fulfilling that goal. The problem was that we published the reports in a book (in English, not in Arabic) and nobody bothered to read them. From the minister down to the civil servants they were not read within the PA, so the effort was wasted.

The Palestinian leadership today

SN: What is your view of the Palestinian leadership today?

MD: I was in Morocco recently to commemorate 15 years since the death of a former Fatah member, and I asked the PA representative there, ‘What is your strategy for the future?’ I told him that when I was in Fatah in the 1970s the group had made it clear that its overriding goal was a secular democratic state. When Arafat made peace with the establishment of the State of Israel under the Oslo Accords he called for a two-state solution. But today, when I call for peace with Israel and to recognise Israel, I am a termed a ‘traitor’. Current PA officials can call for a one-state solution, support so-called ‘anti-normalisation’ and back boycotts of Israel and be regarded as ‘national heroes’. This is basically our dilemma. The peacemakers in Palestine are being attacked because they want peace. We are labelled ‘collaborators’ or ‘traitors’. This is a major problem.

The current leadership look at Israel and see one entity that doesn’t want peace and wants to throw them out. Yes, Israel is united when it comes to security concerns, but when I look at Israel I see a country with many factions that want peace and want to recognise Palestinian rights. I want to try and empower them and to make them more effective within Israeli society because without those factions we will not achieve the two-state solution.