Meir Kraus was the head of the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research between 2009-2016 and is currently a fellow at the research center at the Shalom Hartman Institute. He has written extensively on options for a political agreement in Jerusalem as part of a wider solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as well as leading track two discussions between Israelis and Palestinians about future alternatives for Jerusalem. In this essay, Kraus sets out with great clarity for the Trump team, or its successor, the challenges faced by peacemakers in Jerusalem, the peacemaking principles that those challenges impose, the lessons of previous negotiating rounds and the various options for reaching an agreement.

Jared Kushner has promised that President Donald Trump’s Middle East peace plan will be submitted in the near future and it will address all the core issues that lie at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Jerusalem, refugees, borders, and security. * But the real question is: will the plan address the core issues in such a way that a solid basis is established for serious negotiations between the two parties?

While Jerusalem, the subject of this essay, is the most complex and challenging ‘issue’ on the path to an agreement between the two sides, leaks suggest the Trump peace plan has not yet grasped the sheer complexity of the city’s unique political and spiritual challenges. And if that is the case, the plan will fail.

In what follows I set out my thinking on what the balanced and feasible option on Jerusalem is for Trump’s team, or a future team. I do so under four headings. First, I define the main challenges posed to peacemakers by Jerusalem and the principles of mediation that can be derived from those challenges to guide negotiators. Second, I examine the lessons from previous negotiations and assess the degree of negotiating flexibility each side has. Third, and on that basis, I set out some options for making progress. In conclusion, I try to offer some insights that can assist negotiators committed to bringing peace to this holy city, whatever option is pursued.

Part 1: Challenges and Principles of Peacemaking

Three main challenges exist on the path to an agreement on Jerusalem: religious and national aspirations, security and prosperity, and human rights and quality of life.

Challenge 1: Religious and National Aspirations – a Mutual Demand for Exclusivity

The question of Jerusalem’s political future is intertwined with the city’s spiritual, religious, historic, and national significance, which each side views as a ‘protected value’ about which they find compromise difficult. With respect to the Old City and Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif, the prevalent approach on both sides is: what is holy to me must be exclusively under my sovereignty and ownership. And yet, to achieve a stable solution, both sides will have to renounce their aspirations for exclusivity and recognise the existence, desires, attachments, and rights of the other. This is a theological and a moral challenge for both sides requiring profound reflections on the roots of identity, as well as reconsidering the most sensitive strands of their national desires and religious aspirations.

Challenge 2: Security and Prosperity – Walls versus Reconciliation

Jerusalem is one urban unit, and most of its infrastructure operates as one system. Nevertheless, the city still can be divided. The Israeli and Palestinian populations live separately, and their distribution within the urban space facilitates a clear distinction between Israeli and Palestinian neighborhoods. Any solution will have to confront the tension between building walls and reconciliation – between separation and living together.

The hostility between the sides, the mutual sense of threat, the yearning for security, and the desire for cultural segregation has created the psychological ground for an agreement based on physical division and separation. At the same time, however, the desire to bring prosperity to Jerusalem, to realise its universal spiritual status, and to enhance the quality of life for all its residents, creates the psychological ground for an agreement based on the notion of a shared city without borders, as befits a multi-faith, multi-cultural city. Some future options are based on the aspiration for separation, others on the promise offered by cooperation.

Challenge 3: Human Rights and Quality of Life

While an agreement cannot repair the sense of injustice that was created in the past, the promise of a better and more just future is necessary for any agreement’s successful implementation. Jerusalem contains about 900,000 residents, 40 per cent of whom are Palestinian, the rest Israeli. The Palestinian community in the east side of the city suffers from a high rate of poverty, a low rate of services, and very poor infrastructure. Looking at the issue of Jerusalem just through the prism of national and religious aspirations can bring negotiators and mediators to ignore the human rights issues and needs of the population. More: some options for the future agreement are likely to worsen the daily life of the East Jerusalemites, deepening a sense of injustice and negatively affecting the chances for an agreement to hold. Justice, human rights and quality of life must be at the forefront of the negotiators’ and mediators’ consciousness when they discuss the advantages and disadvantages of any alternative.

Part 2: Principles for an agreement

Any team of peacemakers must consider how each of these three challenges suggests principles for a successful mediation.

Principle 1: Balancing Religious Aspirations and National Desires

The religious aspirations and national desires will be the most influential barriers on the way to peace and any plan should address these aspirations and desires in a very sensitive, delicate and balanced way. Thus, the plan must look for the most balanced arrangement for the Old City and especially for the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif.

Regarding religious aspirations, the arrangement must not merely allow freedom of access and freedom of worship but also enable both sides to express their religion in equal and balanced ways in their holy sites and on their holy festivals. At the same time, it must take into consideration the status quo determined in the second half of the 19th century and maintained today under Israeli rule. The status quo has given the Waqf the authority to manage daily lives on the site.

Regarding national desires, the best way for the peace plan to balance them is most likely to disconnect the holiness of Jerusalem – the holy sites and perhaps all the Old City – from the questions of sovereignty and ownership and instead establish a Special Regime to manage the Old City area. At the same time, the peace plan should recognise Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem as the capital of the Palestinian State, just as it should recognise Israeli neighborhoods as the Israeli capital. Otherwise the peace plan will not be balanced, and will in all likelihood fail.

Principle 2: Balancing Security and Prosperity

The second principle is security. Jerusalem is a tinderbox and radicals armed with an ideology can violate the arrangements in many ways. Tensions around the holy sites can affect the entire region. The proximity between Palestinian and Jewish neighborhoods also poses a security challenge. In times of peace, many pilgrims and tourists come to Jerusalem, and ensuring their safety is a significant challenge.

Can a peace plan assure security without physical borders, or are physical borders vital for a stable peace? If security cannot be achieved without physical borders, how should the border regime be designed so security is provided but daily life, including daily economic life, can continue for residents?

Taking into consideration the religious and universal status of the Old City, it seems that in balancing between security requirements and the character of this space, a peace plan should define the Old City as an open place without internal walls. Fulfilling security demands in other areas of the city may require physical borders between Israeli and Palestinian neighborhoods.

Principle 3: Implementing Human Rights and Quality of Life

For a lasting peace, the peace plan should ensure full human rights to all residents of the city. Any option should assure the Palestinian residents full citizenship and freedom of movement and employment. The peace plan should grant believers from all religions freedom of access to worship in their holy sites. It should also facilitate improvements to the Palestinian quality of life and encourage investment in the east side of Jerusalem. And because of the high rate of economic dependency between the two sides of the city, Jerusalemite Palestinians should be allowed to make their living in the western side.

Armed with these insights into the challenges and with these principles of mediation, Trump’s peace team can begin to design the framework of an agreement. First, however, it would be beneficial to look at the lessons that can be learned from previous negotiations.

Part 3: The lessons of previous peacemaking efforts

Between 1993-2014, Israelis and Palestinians discussed the challenge of Jerusalem several times.[1] In the Declaration of Principles signed during the Oslo process (1993), the sides committed to discuss Jerusalem within the framework of the negotiations about the final-status agreement. Israelis and the Palestinians then held direct discussions about Jerusalem at the Camp David summit in 2000 and in subsequent meetings. Jerusalem was also discussed in the negotiations held between Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Chairman of the Palestinian Authority Mahmoud Abbas, in the framework of the Annapolis Process in 2007-2008. Most recently, Jerusalem was also debated in the round of talks held by US Secretary of State John Kerry with Prime Minister Netanyahu and Abbas in 2013-2014.

Although the rounds of negotiations were based on the assumption that ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed,’ and so neither any concessions made nor any understandings reached had binding validity, we can learn much from these previous negotiations about the gaps between the sides and the most important ideas proposed to close those gaps, as well as the interests and the areas of potential flexibility of each side.

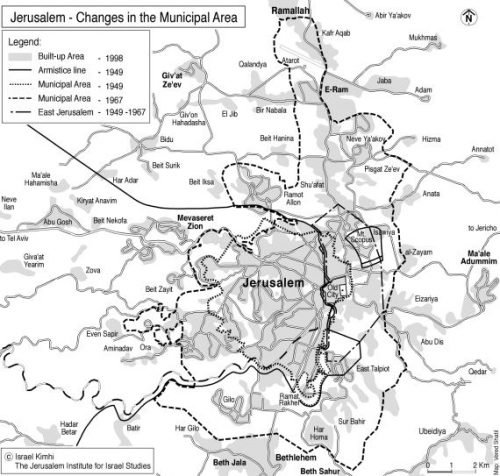

Previous negotiations have established that any agreement will have to address each area of the city in accordance with its historic, national, and religious importance, the character of each area’s population, and its location. The main areas to be discussed are: the Israeli city (the urban area that was within Israeli borders prior to June 1967); Jewish neighborhoods built after 1967 beyond the Green Line; Palestinian neighborhoods annexed to the city in 1967; ‘Jordanian Jerusalem’ prior to 1967; the Historic Basin (also known as the Holy Basin) which encompasses the Old City and the areas adjacent to it, including most of the areas sacred to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; the Old City; and the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif.

The main issues to be considered regarding any of the above spaces in the framework of negotiations are: sovereignty; two capitals; holy sites; border delineation and border regime; security; administrative authorities, municipal services and infrastructure; law and order; residents’ rights and status; economic and fiscal regime; and international involvement. Following the previous rounds of negotiations, any current or future peace team should analyse the different understandings and disputes between the sides regarding the above spaces and issues.

Israeli and Palestinian Neighborhoods beyond the 1967 Borders

The two sides accepted the Clinton parameters (Camp David 2000), which made clear that the division of sovereignty in the city would be based on the principle of ethnicity: that Israeli Jewish neighborhoods will be under Israeli sovereignty and Palestinian neighborhoods under Palestinian sovereignty. This understanding was reached based on the assumption of territorial swaps predicated on the borders from 4 June 1967. The exception being the Homat Shmuel (Har Homa) neighborhood. As it was established after the Oslo Accords the Palestinians did not agree to apply that principle to it.

Map courtsey of The Jerusalem Institute for Research and Policy.

Map courtsey of The Jerusalem Institute for Research and Policy.

The Old City/The Historic Basin

The negotiations about the future of the Old City and the Historic Basin were based on two different approaches: division of sovereignty (the Camp David Process); and special regime (Annapolis Process).

During the Camp David process, guided by the concept of division of sovereignty, it was understood by both sides that the Jewish Quarter would be under Israeli sovereignty, and the Muslim and Christian Quarters would be under Palestinian sovereignty. Both sides requested sovereignty over the Armenian Quarter. In addition, Israel demanded sovereignty over the Western Wall Tunnel, the Tower of David, the Mount of Olives, and the City of David. The Palestinians expressed willingness to make special arrangements to preserve Israeli interests and presence in these areas, but under Palestinian sovereignty.

During the Annapolis process Israel proposed setting up a special international trusteeship to administer the Historic Basin and suggested sovereignty not be determined for the area in the near future. Each side would be entitled to preserve its claims there. The Palestinians neither accepted nor rejected that proposal. The Palestinians opposed a scenario in which the territory of the Special Regime would extend beyond the walls of the Old City, and also demanded that there would be a division of sovereignty in the Old City even if an option of a Special Regime is applied there.

The Western Wall and the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif

The two sides agreed that the Western Wall would be under Israeli sovereignty and the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif be administered by the Palestinians. The Palestinians demanded sovereignty over the Temple Mount compound, but Israel did not agree to this.

Two Capitals, Municipal Administration and Border Regime

The sides agreed upon the establishment of two capitals in Jerusalem, with two separate municipalities, and a joint body to be responsible for the coordination of municipal issues. With respect to the Border Regime to be created between the different parts of the city, the Palestinians supported the solution of an Open City, with no physical internal border, while the Israelis preferred a physical border due to security considerations.

Part 4: Points of Flexibility

Israeli points of flexibility

Israel’s official position since 1967 has been that Jerusalem is a united city under Israeli sovereignty, and that its status is non-negotiable. However, when negotiations were held with Palestinians, Israel presented much more moderate positions. Those positions as well as an examination of Track Two talks allows us to estimate the range of Israeli points of flexibility that may arise during future negotiations.

Sovereignty – Neighborhoods: Israel will insist that all Jewish neighborhoods established beyond the 1967 borders will remain under Israeli sovereignty. These neighborhoods will be at the top of the list for land swaps between Israel and Palestine. It is possible that Israel will give up its demand for sovereignty in most of the areas where the Palestinian population resides.

Sovereignty – Old City: Israel will prefer a Special Regime in the Historic Basin, and at the very least in the Old City, over a division of sovereignty there. If the Special Regime will apply only to the Old City, Israel will insist on its demand for a Jewish presence and administration in the City of David, in the cemetery on the Mount of Olives, and at the Tower of David.

If a division of the Old City is agreed upon, Israel will insist that the Jewish Quarter, the Western Wall plaza, and the archeological park that is south of the Temple Mount, and the leading ways to these areas, will be under its sovereignty.

Holy Sites: It is possible that Israel will agree to designate the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif as being under divine sovereignty, suspended sovereignty, or under the Special Regime. Israel may agree to granting the control and administration of daily life to the Waqf and preserving the status quo that is in place. Israel will insist on its demand for freedom of access for Jews to the Temple Mount. Israel may demand that freedom of worship will include the right of Jews to pray in a limited space on the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif.

Capital: Israel will insist on international recognition of Israeli Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel. If the Old City is designated a Special Regime, in practice, the Old City does not necessarily have to function as part of the Israeli capital. Israel may agree to the recognition of the area, which will be under Palestinian sovereignty, as the capital of Palestine.

Open City: Due to security and demographic concerns, it seems that Israel would prefer a physical separation between the Israeli and Palestinian cities. Israel may allow Palestinian residents to work on the Israeli side. The Old City will remain an open space under the Special Regime.

Palestinian Points of Flexibility

In 2009, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) defined the Palestinian interests in an official document. An analysis of the positions of the Palestinian side following the rounds of talks as well as an examination of Track Two talks allows us to estimate the range of Palestinian points of flexibility that might arise during future negotiations.

Sovereignty – Neighborhoods: Palestinians will insist on their demand for sovereignty in all the areas where Palestinian population resides. Palestinians will agree that Israeli neighborhoods will be under Israeli sovereignty based on the assumption of territorial swaps. It is possible that Palestinians will agree to Israeli sovereignty over Har Homa in exchange for territorial contiguity between East Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

Sovereignty – Old City/Holy Basin: It is possible that the issue of sovereignty will be suspended and that a Joint Special Regime will be determined in the Old City. It will be very difficult for Palestinians to enlarge the Special Regime beyond the Old City to the Holy Basin since it will interrupt the consecutiveness of the Palestinian city.

Holy Sites: It is possible that Palestinians will agree that the Special Regime include the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif. They will insist on granting control and administration to the Waqf and preserving the status quo that is in place. It will be very difficult for Palestinians to grant Jews the right to pray on the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif.

As for places in the Historic Basin to which there is a Jewish connection (the cemetery on the Mount of Olives, the City of David, etc.) it will be difficult for Palestinians to concede their demand for sovereignty, but they will likely agree that Israel will administer these under Palestinian sovereignty.

Capital: Palestinians will insist that East Jerusalem as defined by the borders prior to 1967 (Jordanian City) will be designated as the capital of Palestine. However, in practice, if the Old City is designated a Special Regime, the Old City does not necessarily have to function as part of the Palestinian capital.

Open City: Palestinians would prefer an Open City with no physical barrier, following a division of sovereignty. However, it is possible that Palestinians may agree to a physical division as long Palestinian residents will be allowed to work in the west side of the city and the Old City remain open.

Part 5: Options

Following the analysis of previous negotiations and the points of flexibility of each side, we now draw the contours of the options that could be considered during future negotiations between the two parties and raised by the peace plan team.

Option A: Division of Sovereignty and Physical Division in Jerusalem, including the Old City

This option proposes the division of sovereignty in the city as well as its physical division between the two sides, as follows: all Jewish neighborhoods will be under Israeli sovereignty, and all Palestinian neighborhoods under Palestinian sovereignty. The Jewish Quarter in the Old City will be under Israeli sovereignty, and the Muslim and Christian Quarters under Palestinian sovereignty. The Israeli city will be the capital of Israel and the Palestinian city will be the capital of Palestine.

Option B: Division of Sovereignty and Physical Division in Jerusalem, and a Special Regime in the Old City/Historic Basin

This option proposes the division of sovereignty in the different neighborhoods in the city, similar to that proposed in Option A, but in the Old City/Historic Basin there will be a Special Regime jointly administered by both sides, by an international body or by some combination of the two. Sovereignty over the area where the Special Regime will apply will not be defined. The Israeli city will be the capital of Israel, and the Palestinian city will be the capital of Palestine.

Option C: Jerusalem as an Open City – Division of Sovereignty between the Two States with no Internal Physical Border between the parts of the City

According to this option, the sovereignty of the city will be divided in a similar way to that described in Option A or Option B, but with no physical separation between different parts of the city. The city will remain as one urban unit, and freedom of movement will be maintained between its various parts. An economic-security border will be determined around the city to separate it from the two states.

Addressing the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif

The most sensitive challenge is the Temple Mount /Al-Haram Al-Sharif. The arrangement reached should not give any advantage to either side, regarding both religious and political aspects. At the same time, the options for an arrangement regarding the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif will be examined in light of the extent to which they change the status quo. Due to the great sensitivity of the issue, there is a tendency to adopt the status quo and to perpetuate it, and options put forward to change it are perceived as being low priority. However, preserving the status quo is not the most balanced arrangement. The status quo is crucial in times of conflict to avoid violence and tensions. Yet, in the framework of an agreement seeking to end the conflict, it is possible to consider an alternative balanced arrangement for the Temple Mount in a peace plan, which might include:

- Joint recognition by both sides that the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif is a Muslim holy place on the one hand, and a holy place for the Jewish people, on the other hand.

- No sovereignty will be applied at the site. Israel will have to remove its sovereignty from the area. A Joint Committee (Israeli-Palestinian-Jordanian and perhaps other entities) in partnership with an international body will supervise the implementation of the arrangement and its maintenance.

- Arrangements for the practical expression of Jewish ties to the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif will be implemented. Defining a limited place for Jewish prayer at the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif should be considered.

- The Waqf will administer daily affairs at the site as it has been doing for hundreds of years. Actions related to changing the character of the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif, such as public works, archeological excavations, planning and construction, and visits by non-Muslims will all be jointly coordinated by the two sides.

- A joint/international force will be responsible for security and public order.

Evaluating the Options

The religious-national aspect and security dimension will probably have the biggest influence on decision-makers when they consider their preferred alternative. So, the options should be examined for the degree to which they offer the most balanced answer to the contradictory religious and national aspirations of both sides and, of course, best address the unique security challenges of Jerusalem.

The options must be examined in light of their potential feasibility: is it legitimate, will it be stable? It must be asked, to what extent will each option secure political and public legitimacy in Israel, among the Jewish and Palestinian peoples, in the Muslim world and in the Christian world. The potential stability of each option should be assessed in terms of Israeli interests, Palestinian interests, the daily needs of the populations and urban fabric of life, the expected cooperation between the sides and the level of commitment of international partners.

Part 6: Insights for negotiators

The following insights, derived from a comprehensive search for the most balanced option for an arrangement, should be considered by the peace plan team.

Option B, which presents a Special Regime for the Old City/Holy Basin and preserves this area as one unit while dividing the rest of the city, appears to be the most balanced option regarding the religious and national aspect as well as for security dimensions. It better responds to the main challenges any agreement in Jerusalem has to face.

Disconnecting the Old City/Holy Basin as well as the Temple Mount/Al Haram Al Sharif from the issue of sovereignty helps to overcome the unsolvable argument between the sides regarding sovereignty. It facilitates a way to balance contradictory national aspirations in the Old City, while managing the Old City/Holy Basin as one unit reflects its universal status, enables the city to flourish and serves its spiritual goal.

Dividing the rest of the city between Israeli and Palestinian neighborhoods and recognising the two parts as the respective capitals of the two states also contributes much to the balancing of national aspirations and better addresses the security challenges as well as the demographic challenges than does an open city. Division also maintains the character of the different parts of the city.

Maintaining the status quo regarding the daily management of the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif, Israeli recognition that the site is a holy Muslim place, and withdrawing Israeli sovereignty from the Old City can all help assure Muslims that nobody will change the character of the site, and that it will be preserved as Muslim holy place.

Muslim recognition of the ties of the Jewish People to Jerusalem and to the Temple Mount/Al-Haram Al-Sharif, implementing freedom of access and worship by giving the Jews the option to express their ties in the mount in a limited place for prayer will provide a balanced answer to the religious aspirations of the Jews in their holiest place.

Striving for Public Legitimacy

While looking for the most balanced agreement, public legitimacy can be achieved by highlighting the advantages for each side. The advantages for the Israelis in implementing option B are: division of the city will ensure the Jewish character of Israeli Jerusalem, increase the security and tranquility in the city, and ensure international recognition of Israeli Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and international recognition of the Jews’ religious and historic ties to the Temple Mount. Although Israel would remove its sovereignty from the Old City, Jews will get the option of expressing their religious ties in the holiest place – the Temple Mount – after many generations of longing.

The advantages for the Palestinians in implementing the alternative above are: East Jerusalem will be internationally recognised as the capital of the Palestinian state; Palestinians in Jerusalem will not live under a foreign regime anymore; Israel will remove its sovereignty from the Old City and Palestinians will be an equal partner in managing the Old City; and although the Jews will get the option to express their religion in a limited space, the agreement will assure and confirm the status of Al-Haram Al-Sharif as a Muslim holy site managed by the Muslim Waqf. To both sides’ advantage, the agreement will transform Jerusalem into an international tourist destination and thus ensure its prosperity for the sake of all its residents.

Conclusion:

The purpose of this article has been to draw the contours of a possible agreement regarding Jerusalem. The peace plan team as well as future mediators should be highly aware of and sensitive to the very complex and unique challenges of Jerusalem while seeking a solution. Without a deep understanding of the delicate and crucial balance between the religious and national aspirations of both sides, between security and prosperity and between ‘big’ questions like national challenges and ‘small’ questions like human daily life, there will be no solution.

Has President Trump’s team engaged deeply with all of these sensitive challenges? Only time will tell. Unfortunately, analysing the administration’s steps in the Middle East over the past two years, I have some doubts but I cannot give up hope. If this article contributes to deepening the understanding of those who are still working on the peace plan and making them aware of these sensitivities, then the article may serve its purpose, and maybe one day we will experience peace in the city of God.

[1] The analysis of the history of the negotiations on Jerusalem is based on Lior Lehrs, Negotiating Jerusalem, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2013.

* My thoughts on the geopolitical challenges of Jerusalem are inspired by many discussions with colleagues at the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, who have shared with me their knowledge and analysis over many years. Nevertheless, the insights expressed here are entirely my own.