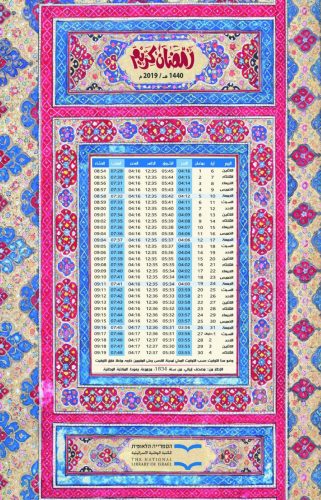

There are signs of a revolution at the National Library of Israel. One is an 8 x 7 magnet bursting with opulent blues and rouge. In its middle is a rectangular timetable in Arabic. In honour of Ramadan, Jewish and Muslim colleagues have joined together to design the library’s first-ever Imsakiyya, a calendar depicting the starting times of the five daily prayers. Royal blue columns highlight the precise time when the fast starts and ends, the dates framed by an image hailing from the National Library of Israel’s celebrated Yahuda collection: a glorious Iranian Qur’an from 1834CE.

(Photo Courtesy of the National Library of Israel)

The collaboration and creation of such a classically Muslim article in what was once known as the Library of the Jewish people is transformative.

‘Twenty years ago, the library was a closed academic institution with a strong Jewish orientation,’ explained Dr. Raquel Ukeles, curator of the Islam and Middle East collection. ’Arabs and Muslims in Israel weren’t considered a constituency or target audience. Now, you’ve got the library producing an artifact that is only logical in a Muslim cultural context.’

While the National Library has regularly created gifts for Jewish festivals, such as digital postcards for Rosh Hashanah and facsimiles of Haggadot for Passover, this is the first time it has created an artifact connected to the Muslim holiday calendar.

Calendars structure human time, a chronological grid that articulates a worldview. In Israel, the Jewish calendar is the national calendar, with Jewish festivals and Israeli national days serving as landmarks in time that are palpable on the streets, at school, in the media. The Israeli calendar tends towards cultural insularity, marking Jewish religious and secular holidays, and the start and close of the Jewish Sabbath. However, although more than one million Muslims celebrate Ramadan in Israel, the holiday is almost absent from public space. Perusing Israeli calendars for nearly 30 years, this writer has never seen a Jewish calendar that marks the start of Ramadan, the month-long festival for Muslims involving fasting during the day and feasting at night. Several Muslim employees said creating an aesthetic, high-quality imsakiyya timetable, embedded with the logo of the National Library, sends a message: ‘We see your culture and religion, and they matter to us.’

The idea to produce an imsakiyya was born out of a lecture by a Muslim colleague about Ramadan for the Library staff. A Jewish staff member at the lecture asked, ‘Hey, why don’t we make one?’ A team of Muslim and Jewish employees coalesced, drawing on skills in education, digital projects, manuscripts and public outreach. Scrambling, the team compressed a month-long process into a few days.

It was a pioneering labour of love. ‘Working on something that constitutes a central part of Muslim households during Ramadan stirred me and motivated me to do my best,’ said Ranin, 25, a member of the educational staff who also works on digital Arabic projects. When the delivery came in from the printer in Ramallah, team members raced to the boxes. Ranin opened one and lifted the magnet with both hands. Beaming, she gushed, ‘My baby!’

Then she and other Muslim colleagues took their ‘baby’ out onto the streets. That gift, deemed a manifestation of inclusion and respect, was hand-delivered to principals and teachers at 22 elementary and high schools across four neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem that are connected to the library in different capacities, as well as across the greater community at large. National Library employees were greeted with warmth and joy. The most common response: ‘This is the most aesthetic imsakiyya I’ve received this season!’

The Library’s cultural revolution goes beyond the calendar, including educational programmes for thousands of schoolchildren, educators and community members in East Jerusalem; a residency programme for Jewish and Arab writers; cultural evenings for the general public; courses on Islamic manuscripts and Islamic calligraphy; a mammoth project of digitising 200,000 pages of Ottoman and Mandate-Era Palestinian Arab newspapers called Jrayed; and an Arabic Facebook page and monthly newsletter.

The Islam and Middle East collection, more than 90 years old, is one of the Library’s core collections and purchases more than 2000 Arabic books annually from across the Arab world.

The National Library also recently hosted an event to celebrate Ramadan, aptly titled ‘Islam Now’, acknowledging Islam in the Israeli public sphere.

‘These projects affirm that the National Library is not just a collection of books. It is proactively doing things to promote a cultural dialogue, something deep and significant, and it’s most welcome and praiseworthy,’ noted Dr Khalid Abu Ras, a scholar, philosopher and practitioner of Islamic mysticism. ‘I myself learned things about my village, Illut, near Nazareth, from a newspaper clipping from 1938 that I accessed through the library archive.’

Part of Abu Ras’s daily routine includes checking in with the National Library’s Arabic-language Facebook page.

Over the past decade, much has changed in the physical landscape of the National Library. Arabic names have been added to the library’s main sign and halls. While there was one Arab member of staff in 2010, today there are 26. Thousands of Palestinian schoolchildren speak Arabic freely in the hallways. Since 2013, nearly every year has featured programming to mark Ramadan. This year’s programme included five TED-like talks about Islam, an iftar, and a DJ playing Islamic house music.

Jewish staff members have started to become familiar with and take pride in the world-class Islam and Middle East flagship collection, one of the best in the Middle East.

In fact, there was an unexpected rush on the imsakkiya on the part of Jewish employees of the library and educators who grabbed hundreds, whether drawn to its aesthetics or to give to Muslim acquaintances, leading staff to scramble and hastily print another 500.

It’s certainly a sea change. ‘I remember back in 1989 being frisked at the door when all I wanted to do was browse the collections,’ said a Palestinian Muslim patron who was checking out books.

These shifts are especially meaningful when one considers the sensitivity around the National Library of Israel. Books and other materials collected by teams of Israeli librarians and solders from Palestinian homes in 1948 constitute part of a collection of about 12,000 volumes that are on deposit at the Library and are catalogued under the call number ‘AP’ (Abandoned Property).

This element is not swept under the rug. Last summer, the National Library sponsored an eight-day intensive codicology and paleography course that drew international scholars, Jewish and Palestinian professors, students and bibliophiles from across Israel and the West Bank. Among the manuscripts presented, Ukeles acknowledged in no uncertain terms that some of them were seized in 1948. ‘That recognition was very important and powerful,’ said Dr Abu Ras, who participated in the course.

There are those Palestinians who experience misgivings about working with or for a Zionist institution. On the other hand, the Library is working actively to grant opportunities and foster the research skills of students in East Jerusalem and citizens across Israel. A Muslim employee said, ‘It bears mention that I didn’t experience any negative feedback, or comments about the logo of the National Library at the bottom, and as my friend said, in the end, it’s the intention behind the imsakiyya, and that is pure’. For Ranin, there is a passion to encourage Palestinians to visit the library and take advantage of its collection. ‘The Islam collection is part of the land where they live, and it has a lot of rich material of their history in different narratives, including their own.’

Established in Jerusalem in 1892, the Library merged with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1925. For much of the Library’s history, it was part of the university and known as the Jewish-National and University Library. Over the past 20 years, the Library’s identity has been in transition. The 2007 ‘National Library Law’ of the Knesset effectively updated the designation of ‘nation’ from only the Jewish nation to the Israeli nation as well.

Today, the National Library of Israel’s identity combines its historical and contemporary roles, with a dual mandate as both the library of the State of Israel and the library of the Jewish people: national-civic and national-Jewish, elucidated Ukeles. ‘Although the two identities overlap significantly, the main area where they do not relates to the non-Jewish populations of Israel. Indeed, the litmus test as to whether the Library is fulfilling its national-civic role and not only its national-Jewish role is the way it serves the needs of the non-Jewish population of Israel – and primarily, the 1.86 million Arab citizens of Israel.’

‘Given its more prominent public role today, the Library’s outreach work to the Arab community has far-reaching implications,’ observed Ukeles. ‘The Library becomes a microcosm of Israel’s aspirational identity as both a Jewish and democratic state.’

When will Ukeles consider the revolution to have come full circle? Will it be when a Palestinian Muslim heads the Islamic collection, rather than a Jew? The vision and aim reach beyond just one person or position, affirmed Ukeles. It’s about creating broad-based change across the institution. ‘I long for the day when there will be Arab citizens of Israel fulfilling senior positions at the Library and developing Library programmes and goals for the coming generations … ultimately, the goal is for Arabs and Jews to feel equally at home at the Library and to be co-builders of its future.’

Wonderful article, Ruth. A glimmer of hope for a brighter future in Israel.

Fascinating account of an important development

it is nice to see that the library is strengthening its outreach to Arab, Muslim, and, one hopes, soon, other important Israeli communities.

on another note: one hopes that the library is doing a better job at keeping track of the components of its collection & that due care is taken to monitor parts of its special collections that are made available to scholars & others. each part of the library’s collection should be marked in several ways, obvious & concealed, so that the collection can be safeguarded against the predations of thieves posing as scholars, etc.