Dr Yofi Tirosh is angry that she is still devoting ‘most of my time, energy, rage and despair to the rampant exclusion of women – both institutionalised and ad hoc – from growing spheres in Israel’s public life’. An expert in antidiscrimination law and feminist jurisprudence from Tel Aviv University Faculty of Law and a human rights activist and expert who serves on NGO boards and government committees, Tirosh is currently focused on prompting Israeli policymakers to recognise the threat to women’s equality posed by the expansion of sex-segregation in Israel’s military, universities, and workplaces.

Personal Journey

Alan Johnson: Yofi, let’s begin with your own journey. What led you to a life of scholarship and activism for women’s equality? And what has kept you at it?

Yofi Tirosh: I grew up in a ‘Moshav’ in an agricultural community in the Negev region, in the south of Israel where the social fabric was extremely diverse. People arrived there from all over the world, and in several waves of immigration. I grew up with Bedouins and Palestinians and my parents were very active in the community. I stay in women’s activism because my parents taught me a model of life – you can’t just remain in your own little world, you have to engage yourself in the wellbeing of everybody. Women’s inequality has always been important to me, not least because women are present in all of the other oppressed groups – Ethiopian, Gay, refugee and more – so fighting women’s oppression benefits the whole society.

‘Jewish and democratic’: Women’s equality and the two ideological systems

AJ: Let’s first take up a key context for women’s equality in Israel, which is the self-identity of the state as ‘Jewish and democratic’. You have argued that ‘women’s rights raise, perhaps, the most accentuated tension between the two ideological systems’. Why is it and how is the tension expressed? Is Judaism itself necessarily at odds with women’s equality?

YT: Israel has the image of being an extremely egalitarian place in terms of gender. People see images of Hannah Szenes, the paratrooper in Europe, or of the women warriors in the underground in the 1948 War of Independence, or the bronzed women in shorts on the kibbutz. And they know that Golda Meir was one of the first female prime ministers in the Western world. There is a real truth to that image.

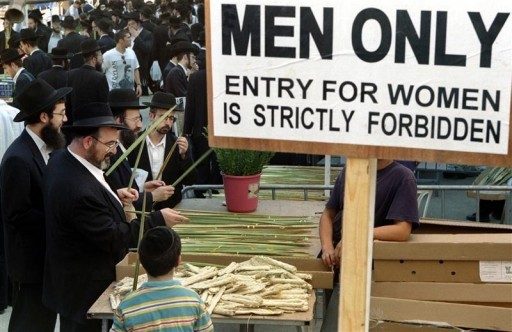

But it is not the whole truth. Since the late 1990s, and especially in the past five to seven years, there is an elephant in the room and if we don’t deal with it, everything else is irrelevant. If sex segregation trends were to continue into the future unchallenged then there won’t be much point talking about sexual harassment or equal wages in the work place, because women will not be in the work place. As inconceivable as that may sound to listeners who know Israel, I strongly believe that we must wake up to the real risks.

Let’s review some history. Often, it was democracy that prevailed. For example, there was a real struggle over the question whether women would have the right to vote in the days before the country was established in 1948. The Zionist parties insisted that women have the right to vote in the face of threats from the religious parties to break the political unity in Jewish Palestine. In other areas, there were grave concessions to the religious that we still pay the price for today. Public restaurants and cafeterias would be kosher, and ultra-Orthodox men would not be drafted because they were to compensate for the loss of the Yeshiva students in Europe in the Holocaust.

More importantly, David Ben-Gurion conceded on family law. In matters of divorce, marriage, inheritance and personal status, Jews in Israel are under Jewish rabbinical law. There is no civil marriage in Israel, and that doesn’t only pertain to Christian same-sex marriage. It means that every couple in Israel, if they want to marry, either go to a Rabbi and are subject to rabbinical law, or they live as domestic partners, or they go on wedding package tours to places like Cyprus and get married outside of Israel. Most Israeli couples are under Jewish law when it comes to divorce, too. The bench is occupied by only male religious Rabbis, women don’t have a theological equality, and the rules of divorce are centuries old. This means that men have a veto about divorce and can ensure women are unable to remarry. It means that matters of property and child custody are decided by old religious men. The Jewish religion has cost Israeli women. When I say ‘Jewish religion,’ I don’t mean Judaism per se, I mean Judaism as it has been frozen and practiced in a very inflexible way by the Orthodox Jewish community in Israel.

In areas not connected to sex equality, the Rabbis are very creative. They will find a way to enable the elevator to run on Shabbat, even under Jewish law. But when it comes to women’s rights they are conservative. The political power that religion has been given in Israel today and the stagnancy of religion in Israel combines to create a major problem for women’s rights today in Israel.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF), the Joint Service Ordinance and sex segregation

AJ: Let’s turn to what you say is one of the key public and institutional sites of the new sex segregation. The IDF has been engaged for two decades in integrating women. However, today, you worry that the arrangements set out in the army’s regulations [the Joint Service Ordinance], which were developed to meet the demands of the country’s religious leadership – and the broad, stringent interpretation given to those directives in individual units – are reversing those advances. What are the new rules, how are they adversely affecting female soldiers and why do you say they will ultimately be injurious to women in Israeli society as a whole’?

YT: Women and religious folks have served in the army side-by-side since the start of the country and even before, in the Palmach. But in the last 20 years we have witnessed something new: the army is now seen as a vehicle for social mobility by Orthodox (as opposed to ultra-Orthodox) men, especially if they serve in prestigious, combat roles and command roles. We know the dynamic well. For the first 40 to 50 years of the country the elite, from the kibbutz and the really good high schools in the city, went into the military and gained experience, training, prestige and a network there, which helped them to climb the ladder in the workplace, politics and media. So it is not surprising that the Orthodox have decided to join the military and to seek leading positions within it, combat roles and command roles. That’s the first development.

The second is that women in Israel have also been joining and climbing the ranks of the IDF. The ‘Alice Miller’ case involved a woman who had a civil pilot’s licence when she immigrated to Israel from South Africa. She wanted to join the Israeli Air Force (IAF) and be a pilot. The IAF said, ‘you can’t, because you’re a woman’. She did not accept this answer, and went to see the then President of the country Ezer Weizman, who was from the air force himself. When she told him what she wanted, he said to her, ‘Meida (a Yiddish word meaning ‘young little sweet woman) you are dreaming, the day women will be female pilots in Israel is the day that men will wear socks.’ Those were his exact words. So she went to the Israel Supreme Court, and in 1995 came the revolutionary decision that the military cannot categorically refuse women the chance to become pilots. This led to whole reform in the military, not just in the air force. More and more roles have been opening for women ever since then, from sniper guard to tank guide.

The two developments are contradictory. Suddenly, we had a clash, in my semi-Marxist explanation. Women were occupying some of the prestigious positions, typically secular women, but with the political rise of the national-religious Right, more and more demands were aimed at the military to ‘enable our religious sons a military service that will not compromise their religious observance and commitments as good Jews’. Of course this sort of thing happens in many cultures and societies; it is not an exclusively Jewish phenomenon. Many cultures mark themselves territorially on the backs and bodies of women.

The Rabbis who lead this trend drafted a list of demands for gender segregation in the military. It was not an easy list for the military to accept and digest, and in response the military drafted an ordinance that was so contentious that it lay in the drawer for five years. Only the recent Chief of Staff, Gadi Eizenkot dared to issue it and put it into action. The Joint-Service Ordinance said three things. One, women should be modest and whenever there is risk of immodest encounters between women and men, men will get to say this: ‘I refuse to be next to this women. I refuse to serve in this condition. The woman is a rifle instructor, and in teaching me to use an M16, there is a chance our bodies will touch. Touch is not something, as a religious man, that I am willing to tolerate as part of my military service. I have the right to say to the military, you have to let me have a male guide for using an M16.’

Touch is one thing; another is this strange category of ‘immodesty’. It’s hard for me to understand how a woman can be ‘immodest’ if she is wearing a military uniform, but there have been some creative and sexist interpretations. For example, in the past few weeks we have received testimonies from female soldiers who say that even in the evening, after hours, when on the base in civilian clothes, they are not allowed to wear white tops, shirts, or sweatshirts because there is a risk that their nipples will show around male soldiers.

The restrictions on woman are proliferating. The military now says that a religious soldier (or, more precisely, a soldier that says he is religious, because nobody checks if he is) can ask to be accommodated so that he is not next to female accommodation. Then there is the huge problem they have with women singing, something said to be immodest in the bible. The military says that if there is a cultural event going on in the base, or a local ceremony, for example graduation of soldiers, and there is a woman singing on stage, then religious soldiers are allowed to leave the room. If the ceremony is official and has to do with the government, let’s say Memorial Day, or Independence Day, then the religious soldiers have to swallow it and be there although there are women on stage. Of course, what happens is that in those circumstances, women simply are not on the stage: who needs the conflict? So we have fewer and fewer women singing and fewer and fewer women on the stage. We have received testimony from female soldiers that even when they are in the audience, singing in the crowd with everyone else, they are being ordered not to sing.

Think about the implications. Think about the sheer financial power of the military. Well, one of the things that the military buys is culture. They buy plays and shows from theatres and all kinds of production agents. I have a lot of anecdotal evidence to suggest that the military’s new policy with regard to religious soldiers has been influencing what is being produced in the first place. If I have a women singing on stage in my production and I know that the military won’t buy it, I will simply not put a woman in my production.

The ordinance also says that the dormitories in which soldiers sleep – whether buildings or tents – have to be completely separated and no one from one sex can enter the other sex’s accommodation and lodging. When you read this part of the ordinance, it’s pretty detailed. It sort of feels like the biblical instructions about how the temple is built; it’s very specific.

Even if I were to accept the principle of separate accommodation, the way it has been implemented on the ground is chilling. As somebody who collects these testimonies through Israel’s Women’s Network and other venues, I have heard more than once that a 19-year-old soldier was asked to hide a photo of herself that she had put by her bedside. It was taken when she was in high school and she is wearing a sleeveless shirt. Even though men other than commanders can’t enter, she was not allowed the photo by her own bedside.

To sum up, we now have a military that marks women’s bodies as dangerous, tempting, inherently sexy. It undermines the entire feminist idea that in modern society each of us is a human being first and foremost, someone who can sing, and be a professional. Now, as an 18-year-old young woman entering this institution, you are told from the very first day, ‘Beware. Do not distract men. And if there is a risk that you’ll distract men by your role, what you wear, what you sing, then we will make sure to protect male soldiers from you’. That is heartbreaking for me. I cannot believe that in 2017 this is what Israel looks like.

The body and the law: The ultra-Orthodox and sex segregation

AJ: You have argued that ‘the regulations pertaining to modesty and segregation remind female soldiers and those around them that they are first of all sexual beings who are gauged by their seductive body’. Can you talk about the relationship between the male gaze, the female body and the law because, listening to you, that nexus seems to be quite central to what’s going on.

YT: This is a good spot to talk about another accommodation in the military, this time with ultra-Orthodox (as opposed to Orthodox) soldiers. The ultra-Orthodox or Haredi were waived from military service, and were allowed to study in Yeshiva instead. In recent years, many people, rightfully in my opinion, have been objecting: ‘Hey, we are giving the best years of our lives, and often risking our lives, to serve in the military, and there is a growing segment of Israeli society that is completely exempt’. Yesh Atid leader Yair Lapid ran in the last election promising he was going to draft the ultra-Orthodox and he managed it, to some extent. That gave the military a problem: how to deal in a gender mixed environment with men who in their daily lives do not come into contact with women, other than their mothers, sisters and wives. The IDF’s ‘solution’ was to create units, platoons, and brigades for ultra-Orthodox only. They serve among themselves, they have their special kosher food, praying times, and, as part of the deal, they get a ‘Women Sterile Service’. That is not my expression; it is the term of the IDF. It means that when the ultra-Orthodox soldiers come to the military on their first day to receive their uniform, get their shots, and get their photos taken, the unit sends all women home, and says to the women that they cannot even hand a kitbag or uniform to an ultra-Orthodox man.

Even if we stop there – and can tell you other things that are more chilling – that is an even more extreme version of an arrangement the ultra-Orthodox have in their neighbourhoods in Jerusalem or Beit Shemesh. There, when they go to the pharmacy or bank they do get service from women, still. (It’s going to change if you ask me, but right now in their home cities they do come into some contact with women in those professional service contexts.) Not in the military. But in the military the state is speaking. The state is saying, ‘We concede that a female soldier handing over your uniform is such a challenge for your religion that we will push her aside, we will send her home and she will be marked as ineligible and unqualified and dangerous to do this job.’

But if we don’t stop there, there are terrible stories. For example, about the woman teacher who entered a room of ultra-Orthodox soldiers that serve in a computer unit, only for the commander to inform her that she could only teach them while she sat down. She was not allowed to teach standing up, because her body would have been too present. She had to hide her body behind a table. Another example is of the ultra-Orthodox soldiers who went out to guard the border with Jordan, and they needed to get instructions from soldiers watching on monitors what’s happening on the border. Typically, this job is done by women. The army have identified that women are more willing to do this very meticulous and boring job, and they do it better than men. But when the ultra-Orthodox soldiers came to guard this border, it was decided that the women could talk to them directly through their walkie-talkies. Instead, they have to pass their messages – ‘I see movement in 50 Kilometres, you have to go there’ – to a male middleman, so he cold relay the instruction to the Haredi soldiers. Otherwise, I guess, the world would have fallen in. I know I sound cynical, but I can’t help it.

AJ: I was puzzled by one thing you wrote: ‘The greater public seems untroubled, or at least unaware, of the creeping threats to women’s service conditions. Puzzled because in my imagination so many families have daughters who are serving in the IDF and those daughters must be telling stories.’ So what explains the passivity? Also, is anyone organising opposition to these changes and do the opposition parties have to say?

YT: Isn’t it puzzling! When I talk to young female soldiers, on one hand they tell me the horrifying stories, and on the other hand they shrug and say ‘oh, this is what the military is about’. My first experience of this was when I discovered a command in the military that forbid hugging. No hugging between two friends, it could be two female friends or male friends. The military that I served in 20 years ago was completely different; it was all about comradery and affection, not just hugging, but playing with each other’s hair, or patting each other’s back. All those things are now completely forbidden and men and women get punished for them. So the whole space becomes this space where the body is dangerous, any physical gesture that involves another person is immediately sexualised. For me, when I heard this, I was shocked: ‘What’s going on?’

Many people I talk to about all this say ‘oh okay, whatever, this is the military’. I talk to soldiers when I meet them on the bus or when I interview them. Few are shocked or angry. Few are aware that in their parent’s time you could hug in the military. If you ask me why that is, I think there are several reasons but the main one is that Israeli women, particularly Jewish women, are deeply socialised to be good girls, to be considerate. Any instruction that comes from a Rabbi’ ‘Why don’t you move aside, why don’t you cover your shoulders,’ they don’t argue against because they are considerate and nice. And they think the nation’s unity is at stake.

Their critical instinct are there, of course – you see it when a boss says something sexist and women speak up: ‘This is sexual discrimination and its wrong!’ But they don’t have that instinct so much when it comes to sexist expectations and requirements that religion demands. I’ll give you one example. We recently had a court ruling in a case where an old woman, on a flight to New York, was asked to move because an Orthodox man would not sit next to her. When the case was filed to court by an Israeli NGO, the discussion on my Facebook page and other pages were really split. Some said ‘way to go, she should sue,’ but many other people, often liberal and progressive, said that ‘she’s just making a fuss, it’s not a big deal, and she should try to be considerate’.

Another obstacle in promoting women’s equality in Israel is that it is said that there are ‘more pressing issues’: defence of course, but also territories and peace. Also religion is much more important than women’s equality in Israel. Many people say ‘yeah, church and state is important and women’s equality is important, but we have to sort out other things first’.

Sex segregation in Israeli higher education

AJ: Why is sex segregation spreading into higher education?

YT: Because of what the higher education system has done to accommodate the ultra-Orthodox. Two groups are not participating enough in the Israeli labour market, Arabic women and ultra-Orthodox men. One response to the mass social protests we had in Israel in 2011 – part of a global wave of protest that included the Arab Spring, the Occupy Wall Street movement and so on – was a big effort to attract ultra-Orthodox men into the university. It was a wonderful idea but difficult to achieve. Many voices were opposed. Rabbis feared that if the ultra-Orthodox get into higher education then they will lose their commitment to an observant life. It’s not going to sound pleasant, but I’m going to say it anyway; the ultra-Orthodox are poor, and poverty is a good tool for the Rabbis to keep people in your community under your control. Once they are no longer poor they can move to another neighbourhood, ask questions, send their kids to study in other schools. The prospect of their flock getting highly paid jobs is scary for many of the ultra-orthodox leaders.

Anyway, the Council of Higher Education started a programme. Remarkably, they said to universities and colleges that ‘if you build courses for ultra-Orthodox students, we’ll subsidise you heavily, giving you extra funding for students, and helping you with new buildings.’ But then came all the conditions: courses would not be part of the campus, but will be taken outside the campus, women and men must study in different classes’ and in practice, female professors can only teach female classes.

Male students are not expected to tolerate a female professor standing in front of them on the podium. When I heard that, around 2013, I could not believe it. I tried to initiate a public debate about it, I wrote op-eds, columns, I organised conferences and panels. Nothing happened. Nobody cared enough. So I approached a very good pro-bono lawyer to represent me and 10 other professors from other universities, and together we petitioned the High Court of Justice about this issue. The petition is still moving through the judicial system, but to my satisfaction it has been getting media attention and so that part of the public which reads newspapers is aware of it.

AJ: Some would say, ‘Isn’t it a good thing that the ultra-Orthodox are studying?

YT: Yes, but I would then add two things. First of all, remember Virginia Woolf trying to get into the library in what she called ‘Oxbridge,’ and they don’t let her because she’s a woman? Historically, women only very recently entered the university. And what, the minute you have a pressing reason – such as needing to make ultra-Orthodox men work – you just ask women to move aside, sacrifice their equality, equal opportunity, professional status, and knowledge, and to just accept that they are not allowed in these academic spaces? I think not.

Second, in regards to the students, it is not a case of separate but equal. It’s not equal in those conditions; women don’t get the same scholarships, programmes, etc. Even if they did, the whole symbolic meaning of this system is ultra-Orthodox men saying, ‘Why don’t you move out of my sight please, I don’t want you in my sight, because you’re distracting in a sexual way.’

Two institutions, the military and the university, central to Israeli society, are saying that ‘ultra-Orthodox men are entitled to require women to be put out of your sight, in the work place, in the service industry, wherever it is’. We see that already happening. We have many examples of the ultra-Orthodox demanding, or the state giving way. For example, when a driver accumulates too many fines in Israel the person has to go through a refreshing course as a penalty. Those state-organised courses are offered to ultra-Orthodox men and women in segregation. For example, if you want to take a tour in an archaeological site in Israel, more and more you will be able to choose the sex of your tour guide. Little by little, we are seeing a creeping normalisation. All of our achievements in sex equality are being undone.

AJ: Let me play devil’s advocate and see how you respond. Some people might say, ‘Look, if we respect difference and we desire participation, then the only way we can encourage ultra-Orthodox men or Arab women to enter the workforce, higher education or in the former case the army, is to respect existing cultural norms. Later, after increasing participation and increasing income, we will move onto a second stage, a more egalitarian society.’ I’m not saying I agree with that, but that argument is put by people who may consider themselves liberals or progressives. How would you respond?

YT: Well, in the first place, I’m not at all sure that what prevents ultra-Orthodox men from coming to the university is the absence of segregation. Perhaps of more importance is their leadership, which discourages them from going to school, or their lack of a core curriculum education in their high schools, where most do not study math, geography, biology, English. This is what makes their dropout rates from higher education so high. We also have evidence of ultra-Orthodox men and women graduating successfully from Hebrew University after studying just as any other student did, with nothing to accommodate them other than their prayer time or fasting days. We also have the Open University where many ultra-Orthodox people study, because it doesn’t involve sitting in the classroom.

Second point: even if I concede that segregation matters, I still want to ask where the ‘red-line’ is. There have been requests by ultra-Orthodox to segregate Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox from Mizrahi ultra-Orthodox. I kid you not! The council of higher education refused that, to my great relief. I still want to ask this question: ‘Why are we not as shocked by sex segregation as we are by segregation on the basis of ethnicity?’ Nobody would accept as a reasonable request, ‘we don’t want to study with Arabs in the class’. Yet we hear ‘we don’t want to study with women’ and say ‘okay, we can live with it’.

Third point: everybody says ‘we have to integrate him or her’. I insist that we need to pause and ask this: ‘What kind of society we will be integrating them into, if we concede these requests?’ It will not be a democratic, fair, roughly egalitarian society where everyone has a right to flourish according to their skills and value. And if it’s not that, then it’s not worth it. If we’re not going to recognise Israeli society by the time we accommodate them into it, it’s not a good idea.

Finally, there are voices within the ultra-Orthodox community, mostly women, who say, ‘Listen, this is doing us a disservice, because once we have segregated university programmes, we are unable to choose regular university programmes’. Community pressure is to study in conditions of ‘modesty’ if possible. Every homogenous class, in my experience as a law professor, is not as good as a diverse class: class discussions on any issue in the world are not as good, and so the level goes down. Even more than that, when employers get two job candidates with a diploma in social work from the same university, one in general social work, and one in ultra-Orthodox social work, they know that although both diplomas come from the same university, the ultra-Orthodox diploma is not as good. The student is already disadvantaged going into the job market. I’m not sure we’re doing a service to them.

Also, consider this: what is a university? Its premise is open enquiry, the freedom to ask questions and challenge and innovate: the enlightenment legacy. But if I am in a law school and I teach male ultra-Orthodox students, can I really teach them about the constitutional right to equality while collaborating with their ability to push aside the female students, and reject a female professor. That contradiction is troubling and is not being addressed enough in Israel.

No longer the guardian of rights? The Supreme Court and sex segregation

AJ: You have been engaged in a research project examining the ways in which the Supreme Court has been reviewing women’s exclusion cases. Can you talk about the findings? As I understand it, you have discovered a break around 2010 after which the practice of the court seems to change, yes?

YT: I recently compiled all the case law of the Supreme Court that has to do with segregation. It started with a case about a woman that was not allowed to sit in a religious service municipality, which is state funded. The people on this board take care of burial services and kosher services and the Rabbi said no women were allowed. The Supreme Court said very strictly, equality comes first.

From the late 1980s, for 20 years or so, the Supreme Court was resolute; willing to write down its analysis, provide its reasoning about rights and remedies, and to instruct the state to act. Since 2010, we see a shift, beginning with a famous case of segregation in an Orthodox neighbourhood. The court gave a very long opinion, with lots of rhetoric about how shocking this is in the 21st century in Israel, where women are being forced to the back of the bus, and so on, but its analysis was really void. There was nothing about equality in it. It prevaricated. We don’t want to force women to sit in the back, but we also don’t want to prevent the community from sustaining segregated seating arrangements. The courts instructed that signs be hung on the bus to inform everyone that they can sit where they want, and that supervisors make ‘random visits’. In Israel, of course, this never happened.

The major element of ruling of the Supreme Court concerned the back door of the bus. The court said: ‘We know that women, when segregated, climb on board through the back door.’ So the Supreme Court faced a choice: do we keep the back door open? They decided to allow the back door to be open. That sent a signal to women and the community that this is where women should access the bus and this is where they should sit: at the back. The practice of segregated buses has had a ripple effect to other lines in other cities, even where there is no ultra-Orthodox community.

Since then, the Supreme Court has said to people like me, people who advocate and litigate women’s exclusion, ‘We are not sure that the Supreme Court is the right forum for this. Maybe you should go elsewhere.’ It has been delegating the issue to very low courts, to small claims courts and magistrate courts. So, if you are at a funeral, and the Rabbi says ‘women to the right, men to the left,’ and so the women can’t read the eulogy in the ceremony because they’re women, the Supreme Court is in effect saying, don’t bother us with that, don’t bother the state’. But it is a matter for the state. This is a state managed and state funded graveyard. Discrimination is being privatised. The woman who wants to complain about what happened at the funeral is left as a private individual, with resort to civil courts. It becomes a matter of money and damages and not a matter of the political contract in the country about the balance between the religious and the right to sex equality.

Israel’s Supreme Court in many areas grows weaker, more vulnerable. That’s not surprising because the government has been attacking and delegitimising it for many years now. So it saves its chips for issues that it thinks are really critical. It does not recognise this issue, the issue of women’s equality and public status, as one of these issues. It doesn’t write long, reasoned opinions anymore, and it doesn’t give resolute remedies. It’s heart-breaking.

Take the case of ‘The Women of the Wall’. In 1994, more than 30 years ago, the Supreme Court said, over many pages, that the women’s right to religious freedom has been violated and this is unconstitutional. But when it came to the end of the document and the question of what should be done, and by whom, instead of saying to the police ‘make sure those women are safe, and no one attacks them and throws tomatoes at them,’ they said ‘oh, it’s such a sensitive topic, let’s start a committee’. So nothing happened. Only recently, the latest compromise about the egalitarian space at the Western Wall fell apart. Still, these women don’t have their right to pray. By the way, I mean pray according to Orthodox rules. Nobody is asking that they pray like reform; it’s all according to Jewish law. But even so, it’s so controversial that we throw the hot potato from one place to another.

The abuse of political theory

AJ: Let’s end by talking a little about the political theory of all this. It seems that one of the important influences on your own approach to sex segregation has been the theory of justice developed by the US egalitarian liberal political philosopher John Rawls. You argue that the current changes in law and practice deny women in Israel the enjoyment of those ‘primary goods’ that are necessary if a person is to exercise their right to flourish, to grow and develop. Is that Rawlsian insight important to your approach to women’s equality?

YT: It’s really interesting to me to hear you reflect that to me, because many people in my generation in academia were trained in the early 1990s and 2000s in very non-Rawlsian ideas, i.e. constructionist ideas and multicultural understandings of society. But as you say, right now I find myself having to rely on this older egalitarian liberal language of rights.

I feel that there has been an abuse of the ideas and insights of postmodernism, multiculturalism, and constructionism. For example, the head of the Shas party, Aryeh Deri, recently – in the context of the debate about whether it is legal for townships to fund segregated public events – made this argument: ‘For 70 years women were on the stage, and people like me, and my public were hence excluded from those events and those public spaces. Now it’s finally time to correct that, and move women outside of the space, down from the stage, so that I get my equality and remedy for all those years I was excluded.’ He is taking the language of exclusion that I claim and own, and he is saying, ‘No, no, no; you with your independence, with your silly modern egalitarian ideas are excluding me!’ I hear this twisted argument in many other contexts today. It’s turning the multicultural idea on its head. It’s challenging and heart-breaking for me.

I’ll give you another example. Take a class in feminist theory and at some point, typically towards the end of the semester, you will study the idea of intersectionality, or solidarity between oppressed groups. The idea that women are not just women, that they have a race, class and sexuality. So some of my feminist colleagues now tell me, ‘you are not tolerant enough; you need to realise that these women are not just women, they are ultra-Orthodox women.’ My answer to that is that segregation is about as opposed to intersectionality as you can get! It does not see any other identity except for sex. It does not even see gender; it sees the biological level of who we are. I can yell at the sign that says ‘women to the right, men to the left’ all I want. I can say ‘but I’m a Mizrahi woman, I’m a gay woman’. But to the ultra-Orthodox, all that matters is that I am a woman, and as a woman I should be confined to the status that the conservative world-view allocates to me.

Alan, can I say one last thing? It’s very important for me to share this insight. What needs to be targeted is not the Orthodox or ultra-Orthodox population. The people who can shift the direction of where Israeli society is going on the issue of women’s exclusion are the decision makers, and they are typically secular and committed to the idea of women’s equality. It is the Council of Higher Education that designed a programme in which sex segregation became a part of the terrain of the university. My conclusion from years of being an activist and researcher is that, astonishingly enough, neither in the university system nor in the military have they even paused to consider what the price of all this will be. There was zero discussion in the Council of Higher Education about the potential influence of excluding female professors from male ultra-Orthodox classes. To this day the attitude is, this is a marginal concern, stop complaining. The people calling the shots in Israeli society are not the ultra-Orthodox. Those who are calling the shots have to wake up. They have to see plain the terrible consequences of inscribing separate status in the public realm for men and women.

Thank you for this great Q&A.

I’ve gone through the hasidic system and it’s terribly unfair to those who’ve survived it to want an education. Reforming a system to meet the lowest common denominator when there’s no flexibility on both participants rejects every element of progress towards the protection of individual rights we strive for.

Start with changing education systems in elementary schools.

As part of a wider article I made the following comments about the interview with Yofi, from an anti-Zionist perspective. The full article can be seen here

https://azvsas.blogspot.com/2018/12/buses-universities-airplanes-military.html

In an interesting interview with Yofi Torosh by Alan Johnson [Feminism in Israel | ‘Pious men and dangerous women’: sex-segregation as a threat to women’s equality in Israel – an interview with Yofi Tirosh] in the BICOM magazine Fathom, Ms Torosh, a law lecturer at Tel Aviv University and a ‘human rights activist’ expresses her anger at the growing marginalisation of Israeli women.

Yofi speaks of the time when she served in the Israeli army.

‘The military that I served in 20 years ago was completely different; it was all about comradery and affection, not just hugging, but playing with each other’s hair, or patting each other’s back.’

Which is of course very touching. With the recent increase in Orthodox recruits a woman’s body has become a symbolic threat to religious masculinity and male military prowess. Segregation of the sexes has become the order of the day.

What Yofi forgets is that the Israeli army of 20 years ago is no different to the Israeli army of today in terms of its military and political role in maintaining the occupation of the Palestinians and in supporting the Jewish settlements. When it came to the checkpoints, round ups, kidnapping of children, assassinations and land confiscation, the practices of the Israeli army have not changed. There is no reason to believe that the use of torture or the sexual abuse of Palestinian children of today is a new phenomenon.

What Yofi is really demanding is equality of the sexes when it comes to the oppression of the Palestinians. Israeli Jewish women should, she is saying, have an equal role in the beatings and shootings. What she doesn’t want is a situation where the women make the tea and the men get on with the killing and beatings up.

The situation of the Palestinians doesn’t get a look-in. This is, in essence, one long complaint about the deterioration in the position of Israeli Jewish women in Israel. Nowhere, not once, does Yofi situate what is happening in the context of Zionism and the degradation of Israeli civil society and the growing marginalisation of the left, even left Zionism in Israel. Yofi fails to connect between the open racism in Israel, the ‘Death to the Arabs’ marches, the attacks on refugees and the decline in the position of Israeli women as a whole.

The deteriorating position of Israeli women is a consequence of the growing racism and chauvinism in Israeli society as a whole. Every abomination and atrocity against the Palestinians is justified in the name of the Jewish religion. This is the same religion which, when I was an Orthodox worshipper, meant that women went upstairs in the synagogue and the men went downstairs. Women played no part at all in the service and their presence was not required. You cannot accept the role of the Jewish religion when it comes to the dispossession of Palestinians and then complain when that very same religion is used to justify your own marginalisation.

In a society where there is no equality between Palestinian and Israeli it is inevitable that the relationships between the different genders in Israel itself will suffer. It is no accident that this year alone some 25 women have been killed in Israel as a result of male violence. A violent society begets violence.