The Federation Movement advocates a new political approach to peace in which Israeli law is applied to the West Bank and Arab residents receive Israeli citizenship. The land would be divided into cantons; autonomous districts managing their internal affairs, all under the auspices of a federal constitution which would guarantee the rights of all. Each canton will have its own government and representative council, which will legislate local law and administer education, local government, policing, planning and housing, and the like. The federal government will oversee matters of security, foreign relations and macro-economic policy. The proposal, they argue, does not prevent two states being created in the future, but addresses the real needs of the people who live in the land today. In this short provocative essay, the co-chairs of the Federation Movement, Emanuel Shahaf and Arieh Hess, outline their proposal and its rationale.

Introduction

While the two-state solution in a variety of configurations continues to figure prominently (if not to say exclusively) in the public discourse in Israel and abroad and is frequently mentioned as the only viable solution to the conflict with the Palestinians, its political implementation is becoming increasingly unlikely. The Israeli political system remains for all intents and purposes neutralised when it comes to a political resolution of the conflict: neither the Right which mostly objects to the two-state solution, nor the Left which will probably be too weak to implement the required withdrawal of about 30,000 households from the West Bank should it regain power in the near future, will likely be willing or able to garner the required majority in the Knesset or whip up the necessary public support to carry out such a major national undertaking and the traumatic measures it entails.

Looking at the conduct of Israeli politicians in the recent years, one might be inclined to conclude that by and large, they do not really want a resolution of the conflict since the upheaval likely to be created scares both the public and its leaders more than do the penalties that may be incurred to maintain the status-quo in terms of casualties, loss of international support and economic damages.

Israel, through incessant settlement activity, too much of it beyond the separation fence, has boxed itself into a corner and created realities on the ground that while still not irreversible physically, appear to be irreversible politically.

At the same time, the Palestinian Authority (PA) continues to weaken, losing public support by the day, while the challenge posed by Hamas in Gaza and the West Bank shows no signs of abatement. Having missed several opportunities to put Israel to the test by agreeing to what could be considered reasonable territorial compromise, the PA is relegated to trying to pressure Israel through the services of international bodies, notably the UN, while rallying international public support through BDS and other boycott movements.

The international community, which is engaged with the large-scale influx of refugees and the continuing threat posed by ISIS, has lost interest in a situation where both parties to the conflict are unable or unwilling to engage to the extent necessary to move forward.

The US historically has taken the lead in trying to nudge both Israel and the Palestinians to get their act together, yet appears now to have thrown in the towel. Since Secretary of State John Kerry’s efforts in December 2015, still under the previous administration, there has been no US peace initiative and even now, 10 months after President Donald Trump’s inauguration, it remains to be seen if and to what extent the Trump administration will really engage to secure the cooperation of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government for a workable agreement. The meeting between Trump and Netanyahu last February seemed to indicate that the Trump administration has an open mind and will consider alternatives to the two-state solution as long as it is in agreement with the Palestinians.

Incidental outside pressure on Israel, mainly from EU countries, while annoying and possibly causing borderline economic damage, is unlikely to be sufficient to move Israel towards a negotiated agreement in the foreseeable future.

Another option raised in Israel, a unilateral withdrawal, is politically just as unlikely to materialise as is a negotiated two-state solution. After the 2005 Gaza withdrawal precedent, where Hamas took over the Gaza Strip, it is highly improbable that Israel will give up territory or remove settlers and settlements without getting anything tangible in return from the Palestinians, even if strategic thinking and common sense would call for such a move to keep the two-state solution alive.

Given this rather pessimistic background, what does an alternative approach need to offer in order to substantially improve on the odds for a resolution of the conflict?

- It should be politically implementable in Israel – In practical terms this means that it should be able to command a sizeable majority in the Knesset, i.e. have real support from the Right and the Left.

- While it should be implemented in consensus with the Palestinian population, if not their leadership, it should be executable unilaterally if necessary, without causing major Palestinian resistance. This in order to prevent a drawn out negotiating process that could be imposed by opponents to the process on both sides, and which could result in a long-term continuation of the status-quo.

- It must have substantial international support, in particular by major powers, if not openly, at least silently.

- Beyond a short transition period it must adhere to international law as accepted by the international community. This means first and foremost that it must end the occupation and provide full civil and human rights to the Palestinian population.

- It must provide the Palestinians with immediate tangible benefits, both economic and political.

- It must ensure the security of Israel.

- It should be acceptable to the moderate Sunni nations in the region.

- As a non-permanent agreement, it should have flexibility to accommodate different future political and economical developments in the region.

While this is certainly is a tall order, we think that the federation proposal has a reasonable chance to deal successfully with the above requirements.

The Federation Proposal

The proposal is based on the recognition that the concept of separating the population into two states living side by side in the Land of Israel, which has been the guiding principle of the two-state solution, is not realistic and that a more likely approach, one that will be able to garner the political support necessary, should be based on the integration of the two populations within the framework of a federation.

This concept would enable the economic integration of the Land of Israel, as it is prescribed in Israel’s Declaration of Independence (and in the UN Partition Plan) and would require execution of the following steps:

- Extending Israeli sovereignty over the West Bank, to incorporate that area into the State of Israel and granting full Israeli citizenship to all Palestinian residents who are interested. This would result in a demographic balance of between 60 and 65 per cent to 35 and 40 per cent) in favour of the Jewish population assuming all Palestinians would join in.

- Recognising Gaza as an independent (Palestinian) city-state with limited arms.

- Creating a joint Israeli-Palestinian administration to structure a federal republic of approximately 11 million citizens and write a joint federal constitution protecting the rights of all citizens.

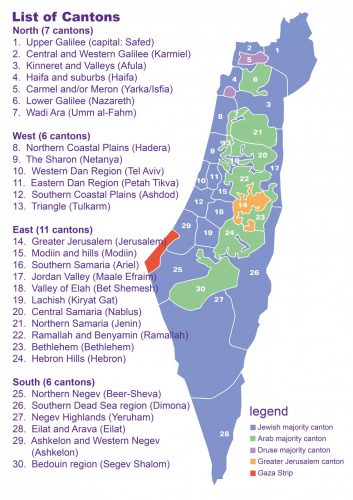

- Preparing and implementing a far-reaching governance reform in Israel including the establishment of regional administrations in 30 largely autonomous regions, 20 with a solid Jewish majority and 10 with a solid Palestinian/Druze majority (five of them in the West Bank) and a federal government based roughly on the cantonal structure of Switzerland, with necessary local adaptations.

- Establishing an upper house in the Knesset where in addition to the Knesset members sent by the public to the lower house, each canton would be represented by two representatives, regardless of size and population of the canton. A double majority clause would prevent a change in the system of government unless there would be both a demographic majority in the federation and a majority of cantons in favour.

An underlying assumption of this proposal is the real pursuit of Jewish-Palestinian equality in a federal republic, both social and economic and a concerted effort to minimise regional income differentials. Achieving this aim requires the establishment of regional democratic administrations representing regional communities – cantons – which will pursue social-economic development at the regional level and enable maximum cultural and religious cantonal autonomy within the bounds of a liberal federal constitution.

The federated state would be a state of all citizens, a civil state and thus create an Israeli nationality (which doesn’t legally exist at this time). This would correct the present anomaly where the nationality of citizens of Israel is ethno-religious (Jewish or Arab) while their citizenship is Israeli. The existing ethno-religious nationalities, primarily Jewish and Palestinian, would find full expression in the regional cantonal governments where each of those national groups have clear majorities. The federal state of Israel would maintain the symbols, flag and national anthem of Israel today. The law of return for Jews would be maintained, there would be no right of return for Palestinians but immigration policy could be liberalised over time with the object of maintaining the demographic balance.

The concept could include an ’exit option’ for the Palestinian cantons in the West Bank whose population would be entitled to vote at some time after creation of the federal republic, (not less than 5 and7 years) if they would like the canton to remain part of the federation or they would prefer to become part of sovereign Gaza. This approach would create a positive incentive for the federal republic to boost the local economy in the West Bank (in order to convince the Palestinian cantons not to vote for separation) and a similar incentive to the Gaza city-state to become attractive enough for West Bank Palestinians to want to join and be its citizens. Regardless of the outcome, should separation become desirable for the Palestinians it would then occur at a vastly improved economic level and will likely not require the large-scale transfer of the Jewish population out of separating Palestinian cantons.

Discussion

The Jewish point of view

The proposal, while appealing to both the political Left in Israel (because of the end to the occupation, an adherence to universal values, international law and a call for a liberal constitution) and the political Right (because of its incorporation of the West Bank within the borders of Israel obviating the need for a withdrawal of settlers, maintenance of a solid Jewish majority in Israel and keeping Israel’s borders secure along the Jordan river) will nevertheless not easily be accepted by the Israeli electorate. The fear of giving up the Jewish nature of the state may be eased by the autonomous nature of the cantons with each canton reflecting the cultural and religious preferences of the dominant population, balanced by a liberal constitution to maintain civil liberties and freedom of religion.

The creation of a state of all its citizens, a constitution and a diminished if solid demographic majority are however drawbacks that will have to be made palatable to the electorate by politicians facing strong opposition. Even so, when looking at the alternatives, a continuation of the status-quo or an apartheid state, our approach does have advantages, the biggest one being that political implementation appears easier since there is no need for a formal agreement, there is no need for a large scale withdrawal of Jewish settlements and the economic well-being of the whole area will improve substantially after a period of adaptation. Existing political groupings on the Palestinian side would integrate into the leadership of the Palestinian cantons provided they would adhere to the constitution of the federacy.

The Palestinian point of view

The proposal does not completely answer the Palestinian need for political independence and the political separation of Gaza from the West Bank is a drawback. On the other hand, the considerable political differences that remain between Hamas in Gaza and Fatah in the West Bank even after the recent apparent reconciliation make such an arrangement, if it is not structured and declared to be permanent, not only possible but perhaps even desirable at this time. Gaza as a Palestinian city-state and regional autonomy in the Palestinian cantons with full citizenship in the federal republic should go far enough to alleviate Palestinian concerns. The economic union with the rest of Israel is a huge bonus for the Palestinians and assures the growth of their economy (and that of the federal republic) and the continued well-being of the Palestinian population in the future.

The refugee issue remains a central concern of the Palestinian National Movement. It must be addressed meaningfully, especially if the federation is implemented unilaterally. The approach could include the following:

- A complete resettling (in the country) of the (local) Palestinian refugees in the camps in the West Bank and Jerusalem in suitable housing, courtesy of the federal republic.

- An international effort inspired by Israel to settle Palestinian refugees in third countries (as envisaged in the two-state solution).

- A partial, limited and mutually agreed upon return of refugees into the Palestinian cantons of the new federal state based primarily on economic considerations.

There is no doubt that the proposal falls short of offering a real equitable solution to the Palestinians – nevertheless it would be a huge improvement over the status-quo and the fact that it would not be a permanent agreement would leave future options for further improvement open, while providing a measure of incentive for peaceful coexistence.

Conclusion

The resolution – even if not permanent – of the conflict, will remain elusive unless there is a major shift in strategic thinking. There is little doubt that the founding fathers of the State of Israel, possibly a majority among them, thought more along the lines of building a liberal democracy for the Jews rather than the ethnocentric nation state with limited freedom from and of religion that is actively being pursued by the Netanyahu government these days.

The economic integration of the Land of Israel was already called for in the UN partition resolution in 1947 and in the Declaration of Independence of Israel in 1948. Moral imperatives, political realities and regional developments in particular, all demand that all the population in the Land of Israel be treated as equals, politically and economically. The quicker that goal is attained, the sooner the threats of internal uprisings and subversion from the outside (ISIS) will subside or become irrelevant. The fastest way to obtain the goal of equitable distribution both of resources and political rights is through the establishment of a federal republic in the Land of Israel, for the Jewish and the Arab population of Palestine, next to an independent Palestinian state in Gaza. This would be completely within the format of Israel’s Declaration of Independence and very likely to be closer to the original plan envisaged by many if not most of the signatories. It would be the most promising move Israel could make to really integrate into the Middle East. While the political echelon in Israel is unlikely to suggest such an approach at this time, the public may be more open to discuss it and possibly embrace it in view of the stark alternatives. This paper is our contribution to this effort.

The proposal reads like nothing much will change. In other words the structure of control and limits of power, both political and economic, will be directed by Israel. Also, it will continue to be a state that has racist laws against the indigenous Palestinian population and confine them as such to bantustans.

The authors refer to adherence to “international law” and in the same breath they advocate the incorporation of the West Bank into Israel which violates international law. Furthermore, with the stress on economic benefits for the Palestinians they hope that there is a strong possibility that they will eventually accept their plight. The idea of economic buy out for the lack of freedom and equality belittles the Palestinians and shows arrogance on the part of the authors.

What erkes one most is that the plan offers the possibility that it will be “the most promising move Israel could make to really integrate into the Middle East”. This will be at the expense of the indigenous Palstinians.

Finally, I note that no reference is made to Jerusalem. One should not forget that the Israeli presence in East Jerusalem is illegal (the same applies to the other compass points of the city). The authors have I presume put the city straight into their pocket.

Referring to Mr. Grays comments I’d like to affirm that there is nothing in the proposal which would make the Federation into a racist construct with racist laws . It would be a state of all citizens with a constitution with the only inequality being limited to immigration and that in order to make it politically acceptable. Mr. Gray credits us with motives not in evidence and I suggest he read the proposal without prejudice, he might then revisit his view. With regard to the legality of annexation it is quite obvious that such a step, if taken would get international support and legitimacy, more so than Israel’s occupation ever did and ever would, provided equal citizenship for Palestinians is part of the annexation.

Isn’t this the Belgium solution?

I would propose a ‘confederation’ of cantons, with the following characteristics:

– cantons are based around cities and directly adjacent suburbs, with a population of around 150,000 people or more.

– less urbanized and rural cantons are based on natural geographic area’s, with a population between 150.000 and 500.000 people.

The reason for this is to make sure different religions and ethnicities learn to live together, to live in coexistence. With ethno-religious cantons you create future problems. Take a look to nowadays Rojava (Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria) for an example.

To make sure national majorities do have ass less power as possible, a system of decentralized decision making should be created. Only foreign affairs and national infrastructure (highways, trains) should be a federal affair.

The name of the country is another problem. Some examples:

– Confederation of Palestine and Israel

– Confederation of Israel and Palestine

– Confederation of the Southern Levant

– Confederation of Cisjordania

– …

I forgot to add four things:

– What to do with the Golan Heights should be an issue of the United Nations. At least should it not be a part of the confederation or Syria must agree.

– United Nations Peace Forces should be temporary be stationed in the confederation (example: 10 years).

– Palestinian refugees have the right to return and the United Nations would assist with that. Advisable is to let them return them gradually.

– First an international court will try to solve disputes between the various groups. Later this court will be run by the people themselves.

So would there be then an integrated army and police – a key element of any state? It just seems so unlikely that this could happen any time soon. The recreation of the Police Service of Northern Ireland as a unified force was difficult enough – could it really happen in a one state solution? I fear without an answer to this question this proposal may not really have traction.