The following remarks were made to a Fathom Forum in London on 3 October 2017. Ebner is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, and her book The Rage: The Vicious Circle of Islamist and Far-Right Extremism is published by I.B. Tauris, 2017.

I started researching The Rage about a year ago when I was working at Quilliam. I was aware of the simultaneous rise of Islamist terror attacks and far-Right hate crimes. After the terrible week in June 2016, when the Orlando nightclub was targeted by gunmen and a few days later here in the UK MP Jo Cox was murdered by far-Right terrorist Tommy Mair, I began to research both extremisms and, in particular, the dynamic between them.

I started to go undercover to events organised by both sides. For example, on 5 November 2016 I began my day by going to Telford to attend an English Defence League (EDL) march against what they term ‘Muslim grooming gangs’ in the town and I started speaking to some of the participants. That evening I attended an event organised by the Islamist extremist organisation Hizb u-Tahrir, about Kashmir. At each I heard the same story of the inevitable war between the West and Islam. One side spoke of the global oppression of Muslims by the West. The other of a Muslim invasion of Europe. And in the fringes of both events was anti-Semitism – often in the form of conspiracy theories.

The dominant theme in both cases is of an ongoing race or culture war between two monolithic units. Both refer to the centuries-old meta-narrative of ‘the Crusaders versus Islam’. Each was fuelling the other’s narrative and providing recruitment arguments for each other. And whilst the European populist parties disapprove of the use of violence, they have a similar worldview. Marine Le Pen, the leader of the National Front (FN) in France, was probed by the police for sharing ISIS propaganda material – of course, to make a point about the threat from Islamism. ISIS also uses US President Donald Trump’s speeches to make a point about how the West is behind the oppression of Muslims.

The Rage shows that the meta-narrative of a ‘clash of civilisations’ can become dangerous once it dominates the discourse on both sides, as it turns into a self-fulling prophecy. The book explores how each side is copying the other’s tactics. For example, violence is justified on both sides by the belief in an ‘inevitable war’ but each argues that preemptive violence is necessary to prevent the other side from winning this war).

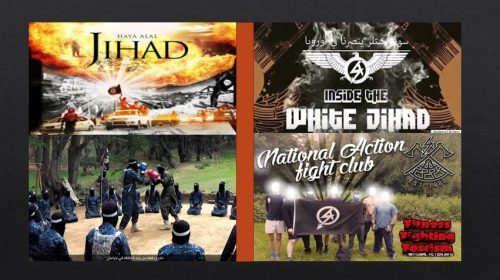

The idea of ‘Jihad’ is mostly associated with ISIS, but National Action uses the notion of ‘white Jihad’ for its propaganda posters. Aesthetically, these resemble glossy ISIS materials. National Action was the first far Right group to be banned by the UK government last year in December. As well as similar propaganda to ISIS, I found that the training camps used by National Action were modelled on ISIS training camps.

Likewise, when we look at the attacks this summer, the first in Charlottesville by a white supremacist who drove his truck through protesters, and then a few days later in Barcelona, it was interesting to see in the encrypted messaging services that both far-Right and Islamist extremists shared pictures of trucks with messages encouraging the use of trucks as the most effective way of killing people en masse.

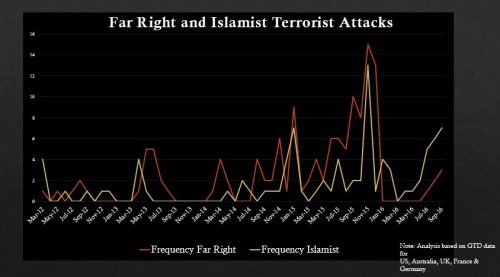

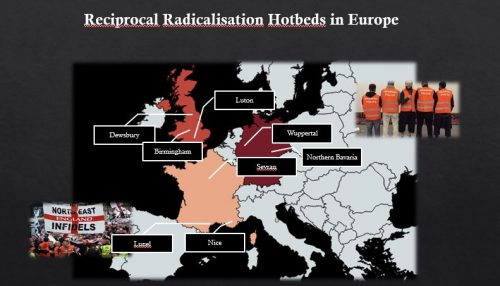

We’ve also seen a rise in the number of jihadi attacks in the US over the past few years. These were matched by far-Right attacks, not in terms of lethality but in frequency. As well as the two attacks I mentioned earlier, there have been arson attacks against immigrant camps, and foiled attacks at mosques in France and Germany. Attacks from both sides spike at the same time. That doesn’t necessarily imply causality, but it does say something about correlation. I took this as a starting point and when I looked into each camp at the micro level I often found a high concentration of extremist groups and violence on both sides in similar geographic areas – often they reacted to one another in a tit-for-tat manner so I called these areas ‘reciprocal radicalisation hotbeds’.

To examine these reciprocal radicalisation hotbeds I carried out field research in the UK, Germany and France and found that there was an increasing interaction of mutual provocation between Far Right and Islamist extremist groups. The most well-known example in the UK is in Luton with the Islamist group al-Muhajiroun and the EDL. But perhaps the most interesting example was the interaction in the build-up and after the London Bridge attack this summer. After that attack I looked into the background of the perpetrators and found that they were all from Barking, which in 2010 had a homecoming parade for veterans from Afghanistan that ended in confrontation between far-Right and Islamist extremists. Each side used the parade for their own purposes.

I spent a lot of time for the book looking online at ISIS encrypted messages services on Telegram and Discord, a gaming application that is the preferred network of far-Right and neo-Nazi groups, and it’s quite intuitive that these channels were full of examples of Islamist violence, which they used to show that Islam is evil and Muslims are invading the West – often a dash of anti-Jewish conspiracy was added to this, as they blamed ‘the Jewish media’ for covering up the terrorist attacks. What was more surprising to me was the level of internal discussion amongst Islamist extremists on the subject of far-Right violence and politics. A recent example was after the Charlottesville rally where one IS-supportive Telegram channel shared a picture of the demonstrators with the caption ‘Nationalism is taking pride in the flag and identity which opposes Islam and its principle’. The Islamist extremists were using the Charlottesville demonstrators to convince their own followers that the US is racist.

In a similar way, Islamist extremists used the election of US President Donald Trump to spread a sense of victimhood and reinforce the myth that the West is against Islam. I spent the election night monitoring how ISIS and al-Qaeda-affiliated channels reacted to the US presidential election and it was interesting to see how many were rejoicing from Trump’s victory, anticipating the large backlash from Muslim communities in the US and potentially driving more Muslims into the orbit of the extremists.

For example, one twitter account said: ‘I wish the British were as vocal in their hatred for Muslims as the Americans are, maybe then the Muslims here would unite against falsehood’. And there were a lot of similar examples on the ISIS-affiliated German networks: shortly after the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) made massive gains in the recent German federal elections, one message said, ‘Germany is electing the AfD, every 1 in 8 German person voted for them, if you deduct the number of those with migrant backgrounds, it would mean every 1 in 5 native Germans voted for them’.

We are witnessing the acceleration of this dynamic of mutual reinforcement and radicalisation: fear is turning into rage and feeding a vicious circle of hatred.

These are some intriguing observations and indeed the 2 groups’ respective rage and fascism feed off and mirror one another. However Ebner appears to ignore how the Islamists are being enabled by a compliant, cowardly and complicit Western establishment, its governments, courts, media, churches, universities and NGOs (at least going by the above commentary). The latter are overwhelmingly proudly Leftist in outlook. And since the denialist Western establishment aids and abets the Muslim radicals – however unwittingly – they help to fuel this spiralling fascist violence from the Far Right and their Islamist enemies.