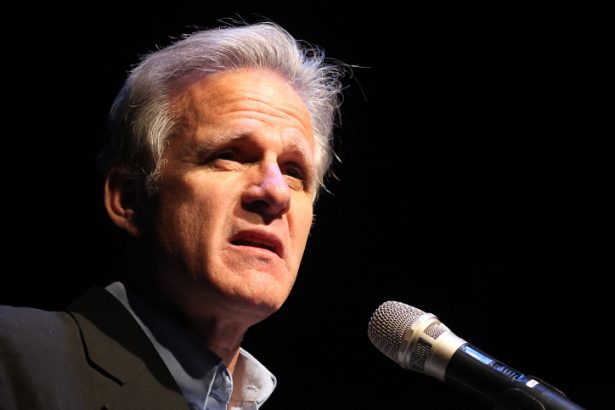

Michael Oren is a former Israeli ambassador to the US and currently serves as Deputy Minister for Diplomacy in the Prime Minister’s Office. He is also the author of Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East. In this interview with Fathom Contributing Editor Toby Greene, Oren discusses the legacy of the Six–Day War 50 years on.

Toby Greene: You’re a historian of the Six-Day War and now a diplomat, as well as an Israeli politician and Minister. If there is one thing you want British policy-makers or opinion-formers to understand about the events of the war itself, what would that be?

Michael Oren: In essence, don’t view the past though the lens of the present, in which Israel enjoys an incalculably better geo-strategic, military situation than it did in 1967. Israel was then at war with Egypt and Jordan plus the entire Sunni Arab world. We had hostile relations with China and India as well as with the Soviet Union and its 12 satellite states. Israel had a friendship with the US but not a strategic alliance; we had no international, great power ally (the French switched sides); and we had indefensible borders. All in all, a very different situation to today when Israel has excellent relations with China and India, and our relations with ex-Soviet bloc countries are some of our best in Europe. We have a strategic alliance with the US, which is probably the most multifaceted alliance Israel has had. Our borders are much more defensible. We have peace with Egypt, peace with Jordan and incomparably improved relations with the Sunni Arab world.

TG: In the foreword to your book you wrote ‘seldom has the world’s attention been gripped and remained seized by a single event and its ramifications. In a very real sense, for statesman, for diplomats and soldiers the war has never ended.’

MO: So true. In fact it is truer today than when I wrote it 15 years ago. With the 50th anniversary approaching, we’re not shooting with guns anymore but rather with concepts and words, and one of the concepts that is going to be ‘shot’ at us is ‘50 years of occupation’ – apartheid, settlements and oppression. We have to respond with concepts such as 50 years of security, 50 years of unity and 50 years of freedom, particularly freedom of worship in Jerusalem which Jews did not have before 1967. So the historiographical battle continues. And in many ways it’s as fatal because what is at stake here is not necessarily our physical existence, as it was in 1967, but our right to defend ourselves and our right to exist as Jewish state, which is being impugned and attacked in the continuing conflict of 1967.

TG: You say ‘50 years of unity’, but what do you mean?

MO: Unity of the land of Israel, which has had a profound impact not only on Jews in this country but on Jews around the world. The 1967 war gave us a great infusion of Jewish identity; for example, the Soviet Jewish movement was deeply inspired by 1967. I doubt there would have been the same level of activism of Soviet Jewry – a movement that changed the course of Soviet history, and led to 1 million Soviet Jews making Aliyah and helping to transform Israel – without June 1967. Without being too reductionist, you can trace so much of this back to 1967.

TG: What would you say really surprised you the most when you were researching for the book?

MO: Two related things. First, the degree to which the Israeli leaders were terrified by the prospects of war. Second, the extent and the length they went to prevent the war. For me the most poignant example is on June 7. With the war basically already won on the Jordanian front and Israeli paratroopers surrounding the Old City in Jerusalem, Levi Eshkol wrote to King Hussein of Jordan to let him know that if he agreed to a ceasefire and a peace process, Eshkol would order the troops not to invade the Old City. So Eshkol was willing to forgo reaching the Kotel [Western wall], in order to make peace with one Arab country. That was an amazing offer. Then. immediately after the war. the Israeli cabinet voted in favour of returning the Golan and the Sinai in return for peace treaties with Syria and Egypt. All this was rejected.

TG: In Six Days of War you write that the diplomatic breakthroughs and peace negotiations that happened after 1967 would have been incomprehensible beforehand. Can you explain your thinking for a British audience which might be looking at the conflict through the lens of occupation?

MO: You can make a very strong the case that the biggest winners of the 1967 war were the Palestinians. For the first time since the Mandatory period, the three main centres of Palestinian population, Gaza, the West Bank and Israel, were reunited under one governance – Israel. That had a profound impact on Palestinian identity. I see it in the Knesset in the form of the Joint Arab List, which is a product of the 1967 war. I see it in the question of Palestinian statehood. In 1967 the word Palestinian almost didn’t exist, and if it did it, it almost invariably referred to pre-1948 Jews living in Palestine. The PLO was a straw organisation set up by Nasser to serve Egyptian interests. Fatah was a tiny organisation founded in the Gulf, there was no talk of a Palestinian state in the West Bank, which had been annexed by Jordan, or in Gaza, occupied by Egypt. It’s only in the aftermath of the 1967 war that Palestinians emerge as a factor in the Middle East and the PLO unites with Fatah and creates a unified organisation under Yasser Arafat. There was no talk of a two-state solution before 1967.

TG: Yet 50 years on the Palestinian issue remains unresolved. And you write that for all its military conquest, Israel was incapable of imposing the peace it craved. Why does Israel’s control over the West Bank continue and we haven’t had a peaceful solution on the Palestinian front and what would it require?

MO: I can think of many reasons that relate to our side, not least of which that this is the Land of Israel and we have a right to it, so it is not easy to convince Israelis that we have to qualify that right because the land is also regarded by another people as their homeland. There is the question of security, particularly in the last five years with the dissolution of Syria and whether we can risk having another failed state on our borders. But the fundamental reason there is no peace is because the Palestinians (as in 1937, 1947 and again in 2000, 2008 and in 2014) have turned down offers of statehood for the reason that they see the price for a Palestinian state as being prohibitive: the price is recognising the Jewish state and they can’t and won’t pay it.

TG: You mentioned the legacy of 1967 for the Soviet Jewry, what do you think has been the legacy of the war for Israeli society?

MO: There are elements in Israeli society – very small ones – who think that everything was good before the 1967 war happened . Yet the vast bulk of Israelis view 1967 as a significant victory and some view it as a religious, chiliastic event which means when God intervenes in history. If Israelis pause and think about what benefits we reaped from the result of the war – peace with Egypt and Jordan, the strategic relationship with the US, defensive borders, strategic depth – we would all agree that the war was the transformative moment for the State of Israel.

TG: One of the things I got from your book was that one of the reasons Israel won was because its sense of insecurity produced an astonishing degree of unity and resilience. Do you think Israel still has that social unity and resilience?

MO: Yes, and I have seen it in the wars we’ve had in the last 10 years. For example, the number of reservists who report for duty greatly exceed the number of those on the rosters and I see how the country galvanises itself in wartime. But the nature of wars has changed significantly. In the next century we are unlikely to see any more wars that end with the phrase ‘the Temple Mount in our hands’. Wars no longer have a beginning and an end. The enemy doesn’t necessarily have a position, a uniform, tanks and plans anymore. It might be easier if it did. And we have to prepare for that.

Why no peace? Mr Oren answers that: ‘I can think of many reasons that relate to our side, not least of which that this is the Land of Israel and we have a right to it, so it is not easy to convince Israelis that we have to qualify that right because the land is also regarded by another people as their homeland. …. But the fundamental reason there is no peace is because the Palestinians (as in 1937, 1947 and again in 2000, 2008 and in 2014) have turned down offers of statehood for the reason that they see the price for a Palestinian state as being prohibitive: the price is recognising the Jewish state and they can’t and won’t pay it’.

This is clearly disingenuous: a sustainable peace requires the Palestinians to not only recognise, but take shared responsibility for the security of Israel; it also requires people like the author to recognise Palestine as a viable independent state, rather than being part of the ‘greater land of Israel’. The details will be complex and difficult to say the least, but the principle is not.

Mr Oren – like those that do not recognise Israel – are part of the problem not the solution. What was the point of Fathom interviewing him, if the purpose was other showcasing 1967 triumphism or identifying a representative of a tune enemy to progress towards peace.?

There is no such thing as “the greater land of Israel,”[sic. per John Newton.]

The definitive legal instrument that underpins in secular international law Israel’s legitimacy is the 1922 League of Nations Mandate.

According to that instrument the Jewish National Home comprises all of the territory between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River.

Israel has chosen to donate the Gaza Strip to Arabs who are under Hamas rule.

If the people and government of Israel were to alienate additional parts of the Home, it would be only for reasons of pragmatism.

Israel has never had an international border with Judea , Samaria and the Gaza Strip, only armistice lines. Those lines merely marked the limits where Israel stopped the Arab aggression of 1948 and consented to an armistice.

Projected negotiations for permanent international borders were refused by the Arab belligerents until only Egypt and Jordan agreed to peace treaties.

The notion that in this conflict (as in others) both sides must share blame is facile and invalid, an attempt to pose as being “fair and balanced.”