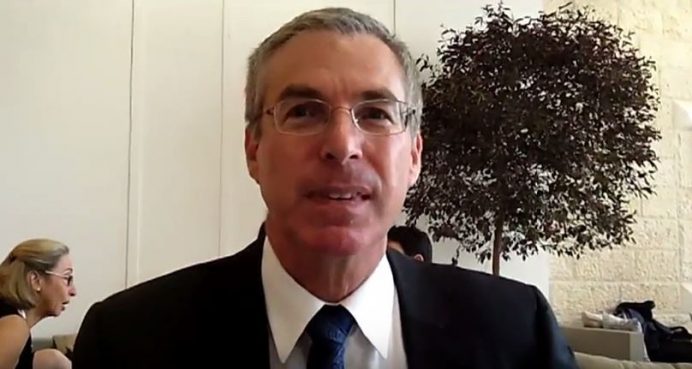

Michael Herzog has been a participant in nearly all Israeli-Palestinian negotiations since 1993. In this important essay, which we hope will be widely read, he argues that while set-piece bilateral talks seeking a final status agreement may be counterproductive in the current climate, there is much that Israel can do now, even without a Palestinian partner, in order to maintain the possibility of a two-state solution at a later date.

A Bleak Picture

From my perspective as someone who has participated in nearly all Israeli-Palestinian negotiations since 1993, the bilateral Israeli-Palestinian arena looks as bleak as I can remember. The last effort at a comprehensive peace solution – the Kerry-led negotiations in 2013-2014 – collapsed, adding despair on both sides to the prospects of a two-state solution. On the Palestinian side, leadership has weakened, with Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) having lost considerable domestic legitimacy according to consistent Palestinian opinion polls, and likely nearing the end of his rule at age 81. He is talking openly about stepping down and people around him are already positioning themselves towards the ‘day after’. The Palestinian Authority (PA) is weak and divided between two political entities, one in the West Bank ruled by Fatah and one in Gaza ruled by Hamas, with the current situation in Gaza resembling a powder keg. For nearly a year we have witnessed a wave of violence (now generally receding with occasional eruptions) in the West Bank and in some cases in Israel, including stabbings, car ramming attacks and other terror attacks against Israelis carried out by young disgruntled Palestinians. On the Israeli side, there is a right-wing coalition, reflecting the reality of Israeli society increasingly turning to the right under the pressure of repeatedly failed peace efforts and Palestinian terror waves. This coalition, some of whose members do not believe in a two-state solution, limits the prime minister’s ability to manoeuvre on the political front, to the extent he wants to. Meanwhile the American role in our region has weakened and the upcoming American elections paralyse potential international initiatives.

The dramatic upheavals in our region offer a mixed balance sheet to the Israeli-Palestinian arena. On the one hand they fragment and destabilise the region, weaken the state system and generate extreme jihadism across the region. Looking at this mess, Israelis and Palestinians should be incentivised to avert further instability in their own bilateral yard. While this unfortunately has not happened, Israel and some of the major Arab states have been drawn closer together by strong converging interests, namely the threats of extreme violent Islamist jihadism, an empowered Iranian-led axis, regional instability as a whole and the weakening US role. In this context some of the major Arab stakeholders, highly concerned about the weakening of the Palestinian system and the potential empowerment of Hamas, are willing to play a role in providing both space and cover to Israelis and Palestinians in advancing the two-state solution. This should be regarded as an opportunity.

Multi-dimensional solutions to multi-dimensional challenges

To address this bleak picture one should look it directly in the eye. After 20 years of failed peace efforts, the first thing to realise is that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is extremely complex, full of grey areas. Simplistic black-and-white characterisations, such as blaming the failure entirely on one party or suggesting that it could be easily resolved if only the leadership were changed, are unhelpful in trying to reach a solution. While Palestinians point to continued Israeli settlement activity in the West Bank and to Israel’s security heavy-handedness, Israelis point to repeated Palestinian rejection of Israeli peace offers over the years, as well as ongoing Palestinian terror and incitement. Israelis rightly push back when Palestinians reject a peace proposal only to subsequently demand that it serve as the baseline for the next round. I have seen this time and again, the most recent example being the US proposal of parameters in March 2014, which to this day awaits a Palestinian response.

There is a natural tendency to single out one specific issue – Israeli settlement policy, Palestinian rejection of recognising Israel’s Jewish character, Palestinian incitement and terror, a return to negotiations, an imposed international plan etc. – and argue that if only that single issue was successfully dealt with, everything else would fall into place. But the challenge is multi-dimensional with inter-connected components and needs to be addressed as such. The pieces of the puzzle include the security situation on the ground and future security arrangements in a permanent status solution; Israeli settlement activity and practices; bottom-up processes of laying the foundation and infrastructure on the ground for future Palestinian statehood, including economic development as well as access and movement on the ground; the situation in Gaza and the relationship between Gaza and the West Bank; creating a top-down political horizon – either through negotiations or through laying out parameters on the core issues; and the regional dimension.

Within the bottom-up development towards Palestinian statehood there is a critical dimension too – often neglected by both the Palestinians and the international community, which I call ‘putting the Palestinian house in order.’ It includes improving governance and fighting corruption, dealing with the division between Fatah and Hamas, and addressing the challenge of transition, post-Abu Mazen. It is easy for the Palestinians to blame Israel for these maladies, yet they are first and foremost their own doing and responsibility. Former Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad showed the way in this direction but was ultimately pushed out.

For now, further bilateral negotiations are not the answer

I don’t see the value in forcing the parties to go back to the negotiating table at this moment. First, there is the challenge of Palestinian pre-conditions. In 2000 (Camp David) and 2008 (Olmert-Abu Mazen), we negotiated without any preconditions. In 2013-14 (the Kerry-led process) Israel was asked to choose one of three conditions – adopting the 1967 lines plus land swaps as the territorial baseline for negotiations, freezing settlement activities, or releasing those Palestinian prisoners held in Israeli prisons since before the Oslo Accords – in order to start the talks. Israel ultimately agreed to release prisoners (although due to incompatible bilateral US understandings with each of the parties not all of the prisoners were ultimately released). Today however the Palestinians demand all three of these elements in addition to an Israeli commitment to negotiate borders first and draw a map within three months. It is hard to see any Israeli government accepting this.

In any case, the two sides remain far apart regarding their red lines on core issues such as Jerusalem and refugees, so even if they were to return to negotiations the talks would likely fail. Moreover, failure is not cost-free, and a fourth collapse of negotiations (following Camp David in 2000, Annapolis in 2007-08 and the Kerry talks in 2013-14), will drive even more people towards despair regarding the future of the two-state solution.

It is thus time to consider different paradigms. The Palestinians are talking about internationalisation of the conflict, modelled after the P5+1 negotiations paradigm with the Iranian nuclear agreement – namely an international setting, where the US is in a minority, which will lay out guidelines and parameters on the core issues in line with Palestinian demands, force Israel’s hand, and absolve the Palestinian side of the burden of concessions. This paradigm will not deliver their desired end-game.

As an Israeli who cares deeply about the future of Israel as the democratic nation-state of the Jewish people[1], I believe Israel should shape its own future and destiny, not just respond to other parties’ initiatives or external attempted dictates. Because the logic of separating the two communities is in Israel’s interest, the country should signal that direction and start moving towards shaping a two-state reality, preferably with Palestinian partners but also with regional and international actors. Even without a Palestinian partner at this stage, Israel should implement a policy of constructive unilateralism that improves its security situation, maintains the possibility of a two state solution and keeps an extended hand open to the Palestinians to renew negotiations at a later date.

Addressing the multiple dimensions of the picture, this policy should include the following components:

Security – Israel should complete the security barrier between the West Bank and Israel (originally built to stop Palestinian suicide bombers and other terrorists from entering Israel) in order to reduce friction between the two sides. While taking security measures against terror attacks, Israel should continue to encourage authorised Palestinian labourers in Israel. Almost all perpetrators of terror attacks have been illegals, and legal Palestinian labour in Israel has proven a stabilising factor.

Cessation of settlement activity beyond the security barrier – This is in Israel’s long term interest and in line with its stated policy of favouring a two-state solution. Israel should not authorise construction in areas where we assume a future Palestinian state will be established. While an international quid pro quo will not be forthcoming, Israel should try and elicit some form of quiet understanding for strengthening the settlement blocs – areas which are essential to Israel’s security and which are widely acknowledged as being part of Israel in a future agreement (based on territorial swaps).

It is hard to envisage Israel unilaterally removing settlements in the West Bank. Following Israel’s unilateral pull out from Gaza in 2005, which included all settlements, it is highly doubtful that an Israeli leader could remove settlements outside the context of an Israeli-Palestinian comprehensive agreement and survive politically.

Additional Israeli measures towards political separation – There is a public debate in Israel on whether to implement measures separating the two communities in Jerusalem. It is complicated politically and legally. However, the current situation in which there is no overlap between the municipal boundaries of the city and the route of the security barrier has bred instability and chaos and should be altered. I would seek to amend the municipal boundaries and adjust the barrier accordingly.

Strengthening the PA’s economic and security capacity – Israel, regional actors and the international community should offer and facilitate (with proper auditing) a significant economic package to boost the PA. Israel should further improve access and movement for Palestinians in the West Bank and upgrade all existing fixed passages. It should also seek to expand its current policy of limiting incursions into area A to security threats the PA cannot or will not deal with.

Area C – In the context of enhancing the PA’s capacity, Israel can and should transfer powers and responsibilities to the PA in Area C (which constitutes about 60 per cent of the West Bank), such as planning, zoning and building adjacent to Area A – even without changing the territory’s legal designation, a task which falls within the purview of the bilateral political negotiations. This was already discussed between the parties and Israel recently announced initial steps in this direction. Israel has also allowed the PA’s police forces to function in Palestinian population centres in Area C and could further expand this.

Palestinian governance – Hand in hand with enhancing the PA’s economic capacity, the international community should pay much greater attention to Palestinian governance. Particular focus should be paid to encouraging a smooth transition to a post-Abu Mazen era, with an eye to preventing it from being chaotic and endangering the stability of the PA.

Establishing a long-term ceasefire in Gaza – Based on the deterrence achieved in the last round of armed conflict in Gaza (2014) Israel should try to achieve a long-term ceasefire arrangement with Hamas in Gaza, involving the PA with an active role in Gaza. Even failing this, speedier reconstruction efforts and fixing basic collapsing infrastructure in Gaza within the framework of coordinated security measures between Israel and Egypt would enhance stability and help avert another violent eruption[2]. Meanwhile, Israel is also in the process of developing a technological solution to detect and destroy Hamas’s network of offensive tunnels

Greater investment in the regional dimension – As noted above, conditions are now ripe for working together with major Arab countries in order to generate progress between Israelis and Palestinians. Egypt is ready to sponsor such a move. Rather than focusing on bilateral Israeli-Palestinian talks, the context should be expanded to include regional actors who can provide both parties with political space and legitimacy. This is important. Israelis would be much more impressed by Arab steps towards normalisation, and reciprocate in the Israeli-Palestinian context, than by anything the Palestinians may offer them.

To facilitate such a regional process, Israel has to relate positively to the Arab Peace Initiative, which it has begun to do. It does not need to embrace the plan verbatim but rather accept it as an important contribution to peace-making in the region. Israel’s prime minister has already sounded some positive notes in this direction, although he did add some conditions.

Some of these regional actors may subsequently play an important role in helping the parties address core issues. Moreover, both Egypt and Jordan could definitely play a role in the security arrangements in Gaza and the West Bank respectively.

Political horizon – While pushing the parties to negotiate currently serves little purpose, creating a political horizon is crucial and should not be neglected. Based on our experience, the initial focus should be on defined parameters for negotiating and resolving the core issues that separate the parties. Israelis and Palestinians failed to achieve this bilaterally and are unlikely to succeed in the foreseeable future. There is a school of thought that advocates such parameters through a United National Security Council resolution (UNSCR) – an idea considered by the French and the Obama administration. However, for a UNSCR to be constructive and serve both parties it has to be balanced (namely addressing both parties’ core concerns), contain elements which are currently rejected by both of them and enjoy broad international and regional support. I do not believe that the Obama administration commands sufficient political clout and has enough time to produce such a resolution and garner the required international and regional support. We should therefore pay more attention to the potential of addressing the political horizon in a regional framework, as mentioned above.

Ultimately out of all the existing initiatives currently on the table, the regional approach has the most potential. The parties should be willing to invest in it and the US and Europe should support it.

[1] The Palestinians deliberately misrepresent Israel’s legitimate demand for mutual recognition between two nation-states serving as a solid basis for ending the conflict as seeking to legitimise Israel’s religious nature at the expense of Israel’s Arab minority.

[2] For a detailed discussion and policy recommendations regarding the situation in Gaza see: http://www.bicom.org.uk/analysis/bicom-strategic-assessment-gaza-can-next-war-prevented/

‘far apart regarding their red lines on core issues such as Jerusalem and refugees’ – refugees or DESCENDANTS of refugees?

With all due respect Michael Herzog what you have written is an impossible quagmire of options and alternatives which will lead nowhere and, even if it did, it wuld leave both parties with gripes which could provoke future conflict.

Why don’t you advocate a peace agreement based upon international law by getting the ICJ involved?

Israelis: if the government of Israel would agree not to destroy any empty

homes, settlements, power and water systems in Jerusalem, Gaza and the

West Bank, then I believe the Palestinians would be more willing to sit

down at a Peace Table to find a long term treaty that both nations would

implement. After destroying all of the Jewish empty homes in Gaza, the

Hamas came into power there because the place was almost demolished.

And destroying empty Jewish homes or the home of a Palestinian who

is arrested in the West Bank causes a mild “civil war” in Israel.