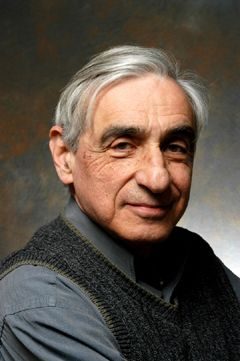

Michael Walzer is professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and one of the democratic left’s foremost political philosophers. His recent essay ‘Islamism and the Left’ – published in Dissent, the US journal he co-edited for many years – sparked much debate on the left. Fathom invited a range of thinkers to respond critically to the essay in conversation with Michael in our offices in London.

Michael Walzer: Thank you to Fathom for organising this discussion about my essay ‘Islamism and the Left’ which appeared in Dissent earlier in 2015. I know you have all read it, so I am looking forward to hearing your critical responses.

Robert Fine (Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Warwick University): Thanks for your article. The primary explanation that you are using for the Left’s condoning of Islamism is its fear of encouraging Islamophobia. But why should there be such a fear? Firstly, the Left is not afraid in the same way of encouraging anti-Semitism. Secondly, as you showed very well in the article, there is no opposition between being sensitive to Islamophobia and being highly critical of Islamism. So, while I thought your description of the phenomenon was very good, I wasn’t immediately convinced by your explanation that the fear of encouraging Islamophobia is the driving force behind left apologetics for Islamic fundamentalism.

Michael Walzer: You could probably say that the fear of Islamophobia is related to the hostility to Israel. There is this eagerness – I’ve heard this often in the States, I don’t know if it happens here – to describe the Islamic minority in the US, or in Europe, as the ‘new Jews’. Somehow, that gives you license to ignore the ‘old Jews’, and to focus on these ‘new Jews’, and to claim that we must not repeat with them what we did to the ‘old Jews’. But that can lead to any criticism being interpreted as hostility to this minority and a way of targeting this minority. The argument becomes ‘if you are critical of Islam, you are joining hands with the new xenophobes of the West.’

Dave Rich (Deputy Director of Communications, The Community Security Trust): I was also struck that this fear of Islamophobia was the central argument. In our experience this reluctance to tackle Islamist extremism for fear of being seen as targeting Muslims and Islam generally is now quite a mainstream fear. In a funny way, it reflects certain Islamophobic ways of thinking amongst the people who are scared of being accused of Islamophobia. It reflects a lack of knowledge and familiarity with Muslims, and a failure to understand the breadth and depth and diversity of Muslim life.

Michael Walzer: That sounds right to me. The fear of Islamophobia is also present among liberal centrists in the US, not just on the Left.

Eve Garrard (Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Manchester): Thank you Michael. If I’ve understood you rightly, you’re suggesting that some of today’s hostility to Israel and the Jews is driven by ‘anti-imperialism’. What I’m interested in is the asymmetries in the argument. Though I’m sure anti-imperialism is playing some role, if we identify anti-imperialism as the source of the hostility towards Israel, then we have a problem: why is the anti-imperialism so selective? That is, why is it the West’s anti-imperialism that generates so much hostility, and not, say, Russia’s imperialism, and so on? It’s that asymmetry that we need to investigate. Do you have a view about that?

Michael Walzer: The asymmetry you talk about is very clear. For me, the clearest example has been friends of mine on the American left who announced that they won’t visit Israel because of the occupation, but are eagerly soliciting invitations to China, despite what is going on in Tibet. They don’t see any problem with that.

James Bloodworth (Editor, Left Foot Forward): I think we face a ‘racism of low expectations’ on parts of the British left. So-called ‘community leaders’ are held up by the Left, but they are often very conservative, elderly, male figures, with a host of reactionary views on things like women’s rights and homosexuality. There are such low expectations on the Left – as if a Muslim person is ‘supposed’ to uphold these very illiberal views.

I also think that there is an unwillingness on the Left to agree with the establishment in any way. So, if you define yourself in opposition to the establishment, then when David Cameron stands up and starts talking about Islamism, there’s an unwillingness to admit that he may be right, albeit for the wrong reasons. I think if you define yourself in opposition to the so-called establishment, it becomes a posture rather than a well thought through critique. You end up in a mess, simply defining yourself negatively, as in opposition to Israel, the US, David Cameron, whatever.

Michael Walzer: Yes. And it’s a problem the other way, also. My article was picked up by the Wall Street Journal. They have a column called, ‘Notable and Quotable’ and they reprinted their chosen three paragraphs from my article. Of course, this was taken by many people on the Left as confirmation that I’m not a leftist at all!

John Lloyd (Contributing Editor, The Financial Times): In the UK, and elsewhere in Europe, the root cause of the recent effervescence of anti-Israeli demonstrations, and their conflation with anti-Semitism, has been the Israeli intervention in Gaza. Over here, Channel 4, a major broadcaster, dropped its (not very strong) commitment to neutrality and became openly anti-Israeli – not anti-Semitic, but anti-Israeli.

Michael Walzer: I think that the Gaza war strengthened the Boycott Divestment Sanctions (BDS) movement in the US. It is important to be closely connected to those people in Israel who thought the war was not a necessary war, that it could have been avoided with a different policy towards the Palestinian Authority (PA) and in the Occupied Territories. But, once the rockets started coming, and once the tunnels were discovered, there was a just cause for a response.

The response was uneven, as I’ve learned studying asymmetric warfare in Afghanistan and Gaza. This was a micro war, a series of very small engagements, and so the character of the engagements depended very heavily on the junior officer in the field. Therefore, different units fight very differently. Some fight very well, in accordance with the rules of engagement that you would want to see soldiers following, and some not. That’s true in the American army, and true in the Israeli army.

I think it’s important to understand the character of asymmetric warfare and to convey it to others. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) were hunting for the tunnels, and Hamas knew where the tunnels were, so they set up traps for the IDF. An army unit would walk into a trap and then everything would depend on the response of the junior officer. If he was calm and collected, he could often get out of the trap. If he was scared, he might call in an artillery strike before he had to, and that is when civilian casualties would happen. If you talk to IDF officers, they will tell you that everything depends on that guy, and that’s also what I heard at the Army War College in Pennsylvania. Everything depends on that person, that 23 year old officer who has to decide, ‘Can I get my men out of this tough situation or should I call in an airstrike or artillery?’

Rashad Ali (Director of the counter-extremism consultancy Centri.): I think there has been a complete post-Foucault reconstruction of left-wing analysis. It is no longer about material factors, no longer about class, no longer about understanding economic power or the construction of society. It’s now about understanding how people posit their identity and how they construct their reality.

So, superimposed on the reality of Islamism is the idea that Islamism is merely a response to Western imperialism. So when Hamas is against Israel, they are held to be actually talking about ‘Western imperialism in the region’. Hezbollah is not seen as a proxy of the Iranian state, but as ‘a manifestation of the people against Western power’. Everything is forced to fit the construct. Post Charlie Hebdo, we saw that a young man had gone to Yemen, came back and enacted the religious edicts he had been taught, finding Jews and killing them, yet he was seen in some quarters as reacting against ‘capitalist imperialism.’ We need a realignment. We need a return to what I would call neo-classical left-wing thinking.

Luke Akehurst (Director of We Believe in Israel): I think my question is a reflection of my own confusion. My upbringing was as a secular and atheist lefty, so I find all of this a completely different world, and tough to get to grips with. What I am trying to understand is that there is (a) the phenomenon that your article was about – the religious fervour happening not just in Islam, but in other religions around the world. At the same time, we have (b) in the UK the population becoming less and less religious. So, there is a massive drop off in our most recent Census of people identifying as Christians – from over 80 per cent to the high 50s. Church of England attendance is dwindling.

So, I am trying to understand whether those two phenomena are related in some way, or if there is one bunch of people in one paradigm, and there are a bunch of other people around the world that are in a completely different paradigm? Or is the loss of religion in the Western mainstream somehow driving the extremism that is happening in other parts of the world, and in some parts of immigrant populations in our own society?

Michael Walzer: It is certainly true that the academic theory of inevitable secularisation seems to have come true in Europe, but not in the US, and certainly not in the rest of the world. I don’t have an explanation. It may just be that Christian zealotry exhausted itself in the 11th century and the 16th century in Europe. I don’t know. But it is true, even in the US, where you have a revival of evangelical Christianity, that it doesn’t have anything like the fierceness that we see among Islamist radicals or Hindu extremists in India, or the Messianic Zionists in the settler movement. It’s not like that; it’s a much milder phenomenon.

I met with the Dissent kids in the office and one of them said to me, ‘There are a lot of discontented, unhappy people and Islamism is what’s there. If the Left was there in a big way, it might attract some of the same people, but it isn’t there.’ That’s why I think the effort to understand the religious revival has to go along with an effort to understand what I call the failures of the cultural reproduction of the secular left. What is going wrong in our world that means civil society is relatively empty of leftist fervour and leftist excitement? When I was thinking about the religious revival in India, Israel, and Algeria, for my latest book, The Paradox of Liberation: Secular Revolutions and Religious Counterrevolutions, my grandson, who studies India at University, pointed out to me that after about 25 years – earlier in Algeria – the Congress party in India, the Mapainiks in Israel, and the National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria became complacent and corrupt. The one thing that the Islamists certainly are is righteous – they don’t take bribes. That is certainly part of the explanation.

My wife Judy and I were in the Northern Galilee a couple of years ago. We went to visit the Trumpeldor memorial. I don’t know how many people here have heard of Trumpeldor, but he was one of the pioneer settlers in the Galilee, to whom is attributed the final words, ‘It does not matter, it is good to die for our country.’ Anyone raised in a Labour Zionist household in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s will know about Trumpeldor. So, we went to the memorial site, but it was empty. There was nobody there but us! That is one sign of what has happened. I think the same thing has happened in India. There’s a wonderful quote that I memorised from a book written by Nehru in 1935. He said, ‘Some Hindus dream of a return to the Vedas, some Muslims dream of an Islamic theocracy. These are idol fancies, for there is only one way traffic in time.’ That was Nehru in 1935, and all of the liberationists believed that. For example, when Ben-Gurion made his deal with the ultra-Orthodox to exempt their kids from the draft, he thought they were going to be like the Menonites in the US, that is, a tiny sect.

David Hirsh: There are some extraordinary arguments lying just under the surface of this discussion. First, when Robert asked why it should be Islamophobia that everyone is afraid of, your answer was about the Jews and anti-Semitism. We have this global problem, and one of our ways of answering questions about it is to say, ‘It’s about the Jews.’ Of course, it doesn’t stop there. We also say it’s about anti-Semitism, so anti-Semitism then becomes a central driving force in the world. That, in turn, is inches away from anti-Semitism itself, for which the Jews are central to everything that goes on in the world. In answering the question ‘why the Muslims?’ you said ‘well, it’s because of Israel and anti-Zionism’, I’m inviting you to comment on the hugeness of this extraordinary position we find ourselves in, that it is … ‘all about the Jews’.

Michael Walzer: I don’t believe that. I was talking about those people on the Left, who I know, a lot of whom are Jews, whose fear of Islamophobia today has a lot to do with their sense of what anti-Semitism once was…

David Hirsh: …I wasn’t trying to be really critical. I think that might be right. Maybe I’m the paranoid one here. Yes, at the very heart of Islamism is anti-Semitism. And the other thing we haven’t discussed is the relationship to fascism, at which at the centre is, amongst other things, anti-Semitism.

Michael Walzer: Yes, but there is also anti-Americanism, anti-Westernism, anti-secularism, and anti-feminism. These are all important features of Islamist politics, but also of the other religious revivalists. I think for the ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel, maybe less so for the settler messianists, the woman question is central to their religious radicalism. I think that is also very important in Islam, the fear of the liberated woman. Therefore, you get, on the American left, this phenomenon of leftists saying, ‘Well, the subordination of women is the way they do things there. We have to be tolerant of the way they do things.’ Any critique then becomes an example of ‘Islamophobia’.

Nikita Malik (Quilliam Foundation): Yes, in India, for example, women joining the Hindutva movement was about power; joining militant feminist movements allowed them to exert power over men who had exploited them. But I wonder, in the case of female jihadists, what the dynamic is. The reports we get from the Islamic State are that women are extremely suppressed in their agency. I can’t see how women’s power would be increased by joining these militant movements.

Michael Walzer: There is an article by Rafia Zakaria in the same issue of Dissent as my piece appeared in. It claims to be an analysis of a woman who told her husband, also an American Pakistani, that she wanted to go to Pakistan and kill people. He was upset.

She pretends to analyse that, but she is actually fascinated, even excited by the idea of a Muslim woman warrior. I think there must be some of that kind of excitement for women recruited from the West. I suspect that when they get to where they are going, they find their readiness to fight is less appreciated. There must be some sense that they are being empowered by this theology. (There is a reply to Zakaria’s article by Meredith Tax that I would invite people to read.)

Alan Johnson: Michael, I thought the essay was a bit soft on Islam. It seemed to suggest that religion is religion is religion – one thing. Sometimes this thing, ‘religion’, being this thing, has a kind of extremist spasm, and these spasms last a long or a short time. But as our mutual friend Paul Berman has taught us, the content of religious ideas really does matter. It isn’t just that the sociological or cultural form of religion matters – the actual content of the particular religion matters. Islam is different. Yes, every religion is different, but each is different in its own particular ways. And we have to attend to these differences.

What was specific to Islam? Its revelation, being unmediated, was different. Its conception of God, certainly not Emmanuel, Father, is different. Most importantly, Mohammed was his own Constantine – a warrior as well as a prophet – and that is very different. In consequence, the space for a separation between religion and politics, between ‘God’ and ‘Rome’ is radically narrowed in Islam. I’m not suggesting for a moment that this is all essential, or that reform isn’t possible, but Islamic reformers do their work on a very particular and very difficult terrain. It is very difficult to ground the kind of values you talk about in your essay – liberty, pluralism, democracy, and so on – on that terrain. So, it strikes me that it is very important to attend to the content of the ideas of each particular religion, as well as the form of religion per se.

Michael Walzer: I guess I don’t know all that much about Islamic theology. I do know that there was a period of Islamic domination in Spain where the Jewish community flourished, far more than under any period of Christian domination. So, there must have been some version of a very liberal Islamic imperialism. There were also fierce Islamists who produced massacres of Jews in the same part of the world, and in the same century. So, I just assumed that these are the possibilities of this religion. But I am quite open to the idea that reformation and enlightenment might be more difficult here or there. I would want to hear from Muslims about that.

Robert Fine: I’d like to say something about the relationship between the representatives and the represented. I was very conscious after Charlie Hebdo that a lot of political representatives talked about how Muslims are offended by the representation of the prophet. The people who said that were often secular people themselves, but they were speaking on behalf of a collectivity who they said were offended. This raised questions in my mind about the relation between representation and the represented. I was glued to the television watching the mass demonstrations in France, in which many Muslim people participated…

Michael Walzer: …including a teenage Muslim girl carrying the sign ‘Je Suis Juif’!

Robert Fine: Indeed! But when you look at the images of the Muslim community in France, it’s not that all the images are wrong – there is some really awful stuff going on in the banlieues – but a very strong majority of Muslims are very integrated in French society. Gilbert Aschar talks about an ‘inverted Orientalism’. I wonder if there isn’t an ‘inverted Islamophobia’ at work also based on a notion of Muslims as elemental, non-reflective, and as not really understanding the rights of others? That is a very spurious image! I am wondering if a concept like ‘inverted Islamophobia’ might not be a useful one for us.

John Lloyd: We should also attend to the sheer attraction of violence. There’s a book about a man called Anders Breivik, who three or four years ago murdered about 70 young socialists in Norway. In the book, it becomes clear that Brievik was not particularly racist; when he was a young man he had friends who were immigrants from Pakistan. He began to get irritated by the immigrants in the estate where he lived with his mother and father. He then spent a few years in his room playing war games on the computer and reading far-right websites. He developed this theory that he has to make some demonstrative act to wake Norwegians and Europeans up to the threat posed by immigration to their culture. He had to do something that would stick in people’s memory. I was struck by the sheer attraction of violence to him. He looked for a rationale. Someone said earlier that when people are upset and unhappy, sometimes the Islamists are there and the Left is not. In Brievik’s case, the far-right was there, and he converted those ideas into violence. Islamism and militant Islamism allow violent fantasies to become real, to have a kind of release.

Dave Rich: This has been a fascinating discussion. It feels to me that your article is about two parallel things: Islamism itself, and left-wing responses to Islamism. Islamism is a very serious set of ideas that needs to be addressed properly. I find a lot of the responses to Islamism on the parts of the Left we are talking about are simply not serious. I think there is a point beyond which we shouldn’t go, in taking the Left seriously when it comes to Islamism.

Ten years ago, when the Left were discussing Islamism in the context of the Western presence in Iraq, Afghanistan, and so on, it all kind of fitted together and provided a context. A lot of their arguments made sense to people then. I think the rise of ISIS today, after Western troops have left the region, the establishment of the caliphate, and the attraction of ISIS and the caliphate to lots of Western Muslims, lots of whom are not that deprived or alienated from society; all this has posed a real challenge to parts of the Left, and they are struggling to respond. The lack of seriousness of their response is becoming more and more obvious, especially because we are also seeing the circulation of alternative and more serious left wing responses.

Michael Walzer: I’m glad to have had the chance to listen to all of you. I do think that the intellectual health of the Left is very important. I don’t want to function as a policeman, but if there is a strong left in the future, we have to win this fight against the knee jerk anti-American, anti-Israel politics, against this kind of moral relativism of ‘that’s just how they do things there.’ We have to address those issues. I agree that the rise of ISIS has made a certain kind of left attitude toward Islamism much more difficult. Yes, I think there is some rethinking going on.

It’s a vital discussion for the Left. Take Syria. I’m not sure what the right thing to do in Syria was, or is, but the debate has not been helped by a certain kind of leftism, which says that anything that the West does, or contemplates doing, has to be condemned. There was an extraordinary moment in the US, after Obama promised to bomb if Assad used poisoned gas. There were big demonstrations against any American military action, but once it was clear that we weren’t going to do anything, even if Assad did use chemical weapons, Syria vanished from the Left’s websites, despite the regime’s use of those weapons, despite its repeated atrocities. For this kind of ‘left’, if the deaths were not our fault, then they held no interest. They were no longer interested in what was going on there, and that’s a sickness.

While not entirely accurate about economic power, Rashad Ali gets the closest to an essential analysis: a “post-Foucault reconstruction of left-wing analysis… [that] is no longer about material factors, no longer about class, no longer about understanding economic power or the construction of society. It’s now about understanding how people posit their identity and how they construct their reality.” That, aside from antisemitism and oil politics, is why the Middle East and Israel-Palestine has become so much the postcolonial left focus.