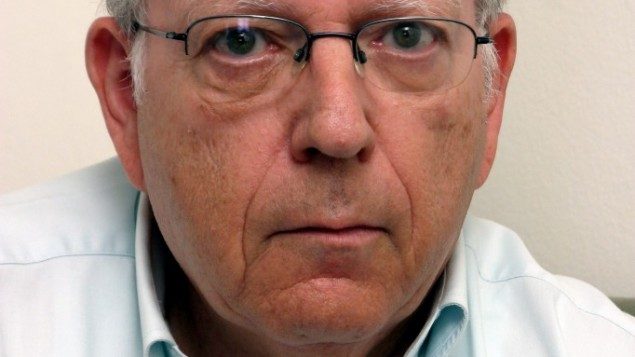

Efraim Halevy was Director of Mossad from 1998 to 2002. Alan Johnson is the editor of Fathom. They spoke on 28 January 2015.

Part 1: The Israeli Elections and the Peace Process

Alan Johnson: You have said that the March 2015 elections in Israel pose ‘a choice the like of which we have never had.’ What is that choice?

Efraim Halevy: I think the choice facing Israeli voters is a choice on the fundamentals of our grand strategy, both defence strategy and political strategy, relating to the future of the Palestinian conflict. There are two clear options. One is to vote for the Likud and the Bennett party [Jewish Home], which means to say, to all intents and purposes, that there will be no negotiation on the Palestinian issue, and we will continue to control the territories indefinitely. The other option is to vote to put an alternative government into power led by the Zionist Camp led by Herzog, with other parties. There will be a very steadfast position on security and defence, including in the North, of course [seven Israeli soldiers had been wounded on the Northern border shortly before the interview began. Ed.]. But when it comes to the Palestinians there will be an attempt to negotiate by a territorial compromise in the West Bank which will result in the establishment of a Palestinian state. I think the choice has never been so clear as it is now.

AJ: If the Israeli public vote for the first option, what happens next? Can the conflict be kept in a holding pattern?

EH: I don’t think that this time round there will be a holding pattern. I think there will be no option but to flesh out a policy, which has not been done up to now. There will be enormous pressure from Jewish Home to begin the gradual annexation of Area C [of the West Bank]. Mr Bennett has made no secret of this in his campaigning. The prime minister [Netanyahu] will not be able to hold out, because he has no alternative. The alternative of simply being in a holding pattern has exhausted itself, I think. It is no longer sustainable. It is not sustainable, by the way, for the Palestinians, the wider Arab world, or the international community. And therefore, this will mean that there will be a clear confrontation between us and the Palestinians, which could lead ultimately to the dissolution of the Palestinian Authority (PA), which will no longer be a useful tool in the hands of the Palestinians, and the situation will degenerate into a third Intifada.

AJ: Sceptics say there is no Palestinian partner for peace, so this is not the time to take risks, or to offer a territorial compromise. How do you respond to that oft-heard objection?

EH: Look, we have a tendency only to look at things from our angle and not to look at events from the other side. My personal history has been a history of trying to look at an issue as best I could through the lens of our own glasses but also through the lens of the enemy, or our interlocutor. The question is not only whether we don’t believe that this is the time, the question is also whether they go along with this idea that this is not the time. From their point of view, there would be a gradual but clear movement in the direction of the annexation of territory and a narrowing of the areas where Palestinians will be able to stake out whatever their status will be, if it will be state or a form of ‘self-rule’ as some people say. Therefore, it will not be possible to synchronise the two timetables.

We often have a tendency in Israel to believe that the only timetable which is relevant is our timetable, and if it’s not conducive to us at this particular point in time to deal with something then it’s obvious that everyone has to fall in line. But this is not the way international relations, or inter-state relations, are conducted. And what this means is, if we insist on freezing the negotiations, or to all intents and purposes abandoning the negotiations, it’s not as if the other side will play ball and say, ‘Ok, you call the tune, and we will fall in with what you say, and we will allow you to do whatever we want you to do. And if a time arises when you think we can talk, we will do, but if not we will simply be dormant.’ That is not the way life is conducted.

AJ: It sounds as if you are worried that Israel is sleepwalking into disaster. That would not be an unreasonable gloss on what you have said. Why do you think there is not a sense of urgency, of impending disaster in the absence of a diplomatic solution? This puzzles a lot of Europeans.

EH: Well, look, we had a 51-day war this last summer. Large tracts of the country were subject to rocket attacks. Most of them were ineffective. Life did not come to a halt but life was disrupted in this country. And they were serous costs in terms of the national budget and the livelihood of the many people. For weeks, Israelis could not go about their lives; but, having said that, once the 51-day war came to an end, life was resumed very quickly. Of course there is a lot of discussion about damages and of course there was suffering. But by and large people have gone back to their daily lives.

As we speak there is an exchange of fire in the North, but cars have not stopped running through the streets of Tel Aviv, no events have been cancelled. It is a problem of the North and the North will take care of it. The IDF has beefed up its presence in the North. We go about this not with equanimity but with a sense of confidence that things will be taken care of, one way or another. I accept that there are people like me, and maybe a few others, who believe that we are on the edge of a volcano. The normal citizen of Israel does not feel it [to be] so. Our stock exchange went up today, and the dollar went down and the shekel went up, and all this is part of a daily routine which has not been disrupted since the end of the war last summer.

AJ: That is a huge strength, making Israel very resilient. Can it also be a weakness, preventing the urgency required on the diplomatic front?

EH: Well, you and I might think so, but, you know, we had 51 days last summer and by and large people thought that the IDF did well. In terms of fatalities, the number of military fatalities was over 70 and of course many wounded, some virtually unconscious with little to no hope of recovery. This did have a serious impact on the public. However, the number of civilian causalities was in one digit; five I think. So, there is not a feeling here that we are on the edge of a precipice.

Part 2: Framing the Threats

EH: The powers that be in this country send a very mixed message. On the one hand the prime minister shouts from the rooftops that Israel is in mortal danger of destruction. Yesterday, again, he took advantage of the occasion of International Holocaust Memorial Day to say that we will do everything we can to prevent a Holocaust. The mention of the Holocaust touches a very sensitive nerve here in Israel, and not only amongst the survivors. I have always said that it is bad thing to use the terms ‘Holocaust’ and ‘existential threat’…

AJ: Why?

EH: Because we are not in a Holocaust situation. Then, six million Jews were herded into compounds and exterminated. And this can never happen again, certainly not in Israel. We have a very effective defence system. If you say there is a danger of a Holocaust it’s like saying the IDF is of no consequence. The IDF is here not only to prevent a Holocaust but to prevent an atmosphere of fear that we can ever be on the verge of a Holocaust. That’s exactly why we build up our defence and our intelligence community. Both serve the purpose of negating the idea of a future Holocaust. There cannot be another Holocaust.

Also, I think it is a terrible mistake to use the term ‘existential threat’ because I do not believe there is an existential threat to Israel. I think the Iranians can cause us a lot of damage, if they succeed in one way or another to launch a nuclear device which will actually hit the ground here in Israel. But this in itself would not bring the State of Israel to an end. I also think that it is a terrible mistake to tell your enemy – in this case, the Iranians – ‘you are an existential threat to Israel, we the Israelis believe that you have the power to destroy us.’ It’s almost inviting them to do so, because they will say, ‘If the Israelis themselves believe that they are vulnerable and can be destroyed then that is sufficient basis to go and do it. Don’t you think so?’

I am now 80 years old. I was born in 1934 and as a young boy I was in Britain in World War Two. I have a very vivid memory of those days. I knew what was going on. And I remember the chats of Winston Churchill over the radio. We used to crowd round the radio receiver and listen to him. At no time, even at the height of the Blitz, did Churchill say that there was a mortal danger to Britain’s very existence. On the contrary, he said even if, in the extreme, the Germans succeed in landing, and even if they overcome resistance and put themselves in charge, we will continue fighting overseas and in the end we will triumph! That’s what he said. And that kept up the morale of the British population. Look, you don’t tell you own people that there is an existential threat. You tell them there is a threat, perhaps a most serious threat, but we are in a position to meet it. We have a lot of means at our disposal, some of which are well-known, some of which are less known. We are not sitting ducks waiting to be destroyed one fine morning.

The prime minister views the British wartime prime minister as his role model – he prominently displays a photograph of the British leader in his office. But, in truth, he is the absolute antithesis of Churchill; whereas Churchill projected power, confidence, strategy and absolute belief in Britain’s ultimate victory, Netanyahu repeatedly mentions the Holocaust, the Spanish Inquisition, terror, antisemitism, isolation and despair as embodied in his frequent allusion to the ‘existential threat.’ It was American President Franklin Roosevelt who led the United States and the free world to victory in World War Two who said ‘There is nothing to fear but fear itself.’ I fear the ‘fear’ that the prime minister of Israel is propagating.

I have said this on many occasions. I repeat it wherever I go. And I strongly object to the prime minister using this term ‘existential’ time and time again. He did it again last night. I think it is a terrible mistake.

AJ: And why is this mistake, as you see it, made so often?

EH: Because the prime minister has his approach to life, very much influenced by his father [Benzion Netanyahu]. When the events took place in Paris the prime minister came to Paris and told the Jewish leadership there, in a closed session, that they were on the verge of a situation similar to the Spanish Inquisition. He recalled the work of his fatherwho was a renowned scholar, a historian of that period in Jewish history, who wrote about Don Yitschak Abrabanel who served as Minister of Finance in the court of King Fernando of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castillia in Spain. It was said that he failed to warn the Jews of their impending fate and he proved unable to thwart the ultimate inquisition and expulsion of the Jews from Spain in the year 1492.The prime minister told the Jews in Paris that they are today in a situation parallel to the situation of the Spanish Jews on the eve of the Inquisition, and that they better be clear as to what it is that they are facing. I think this is really to preach despair as a motive for making Aliyah to Israel and this is abhorrent.

AJ: In Britain there has been debate, sparked by some polls, about attitudes towards Jews. The knowledgeable Jewish community professionals are worried about a distorted depiction of British Jews as a community about to start hiding in cellars. They think that picture bears no relationship to reality. But no one wants to be seen as complacent.

EH: Of course no one should be complacent. You should take precautions. You should know what is going on. In Britain the authorities are very well aware of the threats. The British defence and security system is very effective. Not fool proof, nothing is; you had 7/7 and other events. And now there are people travelling to the Middle East to fight and some will return home and try to prepare terrorist attacks. But the British Security Service (MI5) is very professional. I’ve known them for years. When I served in Europe in the seventies I met Stella Rimington, who later became head of the service, and Eliza-Mannigham Buller who also became head of the service. These two leaders were extremely capable and competent intelligence chiefs as were their successors. The British system now has more expert manpower and capabilities than ever before. There is not a shadow of a doubt in my mind that what must and should be done is, indeed, being done, and ultimate victory in the international campaign against terror is within reach.

Part 3: Israel and America

AJ: There is now a furore in Israel and in America about the controversial decision of the Israeli prime minister to accept an invitation from the US Congress to address a joint session – an invitation issued and accepted, seemingly, without the knowledge of the US president. This is the latest incident in a series of incidents that suggest the relationship is in some trouble. How do you interpret these events? What’s the meaning of the invitation? What’s the meaning of the acceptance? And was that acceptance wise?

EH: I think the entire business of the invitation to the prime minister was woefully handled. First of all, the assessment that the procedures used in this case would be accepted by the administration and the Democratic Party were totally mistaken. When this was announced, Jerusalem let it be known that this was a bipartisan decision in Congress. It was not. We now know that within hours the Democrats dissociated themselves from the invitation saying they knew nothing about it. Then the Speaker said he had the authority to invite in the name of Congress. Yes, but that is not what was said initially. Second, I think the likely reaction of the president was woefully miscalculated. It was obvious he could not take this blatant insult lying down or he would become a damp squib. Moreover the Democrats in the Senate have now lined behind the president and will not support a Republican legislative move to institute an automatic roster of fresh sanctions against Iran and the result is that the prime minister’s forthcoming speech to Congress is doomed to failure from the very start. A presidential veto of this initiative cannot be overturned – it lacks the votes.

All this should have been checked in advance. That is one of the reasons we have an Embassy in Washington D.C. That is why we have an Ambassador whose task is to sound out people in advance and to ascertain how they might respond to this or that initiative. This is the A-B-C of diplomatic activity – to collect information and then to analyse it and send the product back to the political master. But if the Ambassador is a member of the clandestine plot to circumnavigate the President of the United States and his party’s representatives in Congress, he cannot perform the professional role required of him because he deliberately blocs all the access he needs to perform his basic functions.

Last week President Obama visited India and Saudi Arabia. In India he was received almost royally. Prime Minister Modi broke with protocol and personally rushed to the airport to greet the visitor alongside the Indian president. The following day he shared the dais with Modi when the Indian Armed Forces held a parade, including an aerial display of Russian-built MiG aircraft, which saluted the American president savoring this moment in history. The following day Obama flew to Riyadh and there led a delegation that included Secretary of State Kerry and two of his predecessors, both Republican eminent figures, and Senator John McCain – the Republican chairman of the powerful Armed Services Committee who ran against him for the Presidency in 2008. This was a show of bipartisanship towards Saudi Arabia – how different from the clumsy way Israel has trodden on American turf in recent days.

Part 4: We must have a political policy and a political horizon

AJ: Many Europeans, including friends of Israel, find it difficult to work out what strategy is being pursued by Israel. They see a fraying of the relations with the US, to some degree, and with the Europeans; they see the gradual loss of the ‘quality minority’ at the UN; they see increasing international diplomatic isolation with more legal moves being made by the Palestinians, including at the ICC; and they see global public opinion becoming more hostile to Israel. They don’t see the strategy.

EH: In the past, the common wisdom was that in an election campaign everything is permitted, and after the election, you resort to normal policies; and that people should understand this because, as Henry Kissinger said ‘Israel does not have a foreign policy, it only has a domestic policy.’ And that sounds very nice; it’s nice to quip about it. My complaint is that we do not have policy concerning affairs of state and security; we have a negative approach to what is going on around us.

Take the war in the summer of 2014. We fought for 51 days and the prime minister said at the end that Hamas had received a beating like they had never received before. He then said that his aim was that Hamas should gain nothing from this. No port, no airport, no political gain. But you and I know that there are always two sides to the equation when you have a war or military campaign. You have to have a military and security capability to achieve the maximum result. After that there has to follow a policy, the political side of the equation. But if you describe your policy aim as preventing the other side from getting any political advantage there is no positive policy in this. Just maintaining the present situation for a year or two years – this is not policy.

In Israel Hayom – the free newspaper published by Mr Sheldon Adelson, which has the widest circulation in Israel and it is more or less the prime minister’s newspaper – the prime minister said ‘if we had gone to war for 500 days not for 50 days, the price would have been enormous, but the result would have been no different.’ But if this is the case, what is your policy? What do you intend to achieve? What are your political aims for the Gaza Strip? Just that they will not shoot at you? But there are two million people there and they must have the means to live. You can’t simply say ‘my aim is that they get no advantage.’ That is not a policy.

It’s the same with the West Bank. We say we can’t give up any area of the West Bank because the moment we do, we will have Hamas or ISIS on our doorstep, and surface to air missiles on Ben-Gurion [Lod] airport, even shoulder-launched missiles. But today, as we speak, Hezbollah has rockets of all kinds targeted at Lod airport, already, so you can’t say we won’t give up territory 15 kilometres from Lod because of the threat of a strike from the West Bank. Nasrallah can already strike from Lebanon. Or you could bring an aircraft down from some place across the Jordan River, in Jordan. You can stand there with a missile with a capability, a homing device, and in four-five minutes it will be over Lod airport.

We have to hammer out a policy. It has not been done. We remain, so to speak, in a holding pattern. But every aircraft has to land sometime. We can’t stay up in the air indefinitely, going round and round, waiting for a nod from the tower to say you can land. You will run out of fuel! And that is exactly where we are. We are out of political, diplomatic, foreign policy fuel. The fuel tanks are empty.

AJ: Is this lack of policy, as you see it, connected to another problem you have identified, that ‘peace will elude us until we treat the Palestinians with dignity’ as negotiating parties need to feel they are, roughly, ‘on a par’?

EH: Right. We treat the Palestinians as inferior to us. We say that we are very generous the way we treat them. We give our VIP cards to the Palestinian leaders and they have freedom of movement and so forth, so what are they complaining about. But it is we who gave them the VIP card. And so just as we issue it we can withdraw it. See?

I’ll give you another example. About a year or so ago I met an Iranian involved in the periphery of the negotiations of the P5+1 on the nuclear issue. I meet these people quite often on what we call ‘Track II’ meetings. I asked him, ‘How did you feel sitting across the P5+1, it must have been exhilarating for you?’ He said to me ‘You don’t understand. The table was a round table.’ You see? Apropos dignity.

Don’t forget what the crowds were shouting for in the Arab Spring. They wanted dignity. Yes, they wanted a decent salary, but above all they wanted dignity. And we, when we deal with people, we do not treat them with the requisite dignity. Look, Mr Bennett says that when he takes over he will give citizenship to about 70,000 Palestinians and if they do not agree we will just move in and take over. That is not dignity is it?

When Mr Bennett says that Abu Mazen (Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas) is a terrorist – and he says it incessantly – or when Mr Lieberman says Abu Masen is a terrorist, it is degrading. I don’t think Abu Masen is a great friend of Israel and I don’t expect him to be. So he will never be considered as a candidate for president of the World Zionist Organisation. But we should not expect this. He is trying to fight for the survival of his people but we accuse him of ‘diplomatic terror’. What does that mean? He went to the ICC so he is a ‘terrorist’, an arch-terrorist, some say. My Lieberman says he is a terrorist. Mr Bennett says he is a terrorist. And as you know our policy is that we don’t deal with terrorists. So we are saying we won’t deal with him.

AJ: You have said Fatah is a ‘hollow movement’ that is ‘preparing to leave the historical scene.’ Some people claim not to see anyone below Abu Mazen that is likely to be more accommodating, and these people are surprised by this treatment of Abu Mazen, in the absence of that better alternative.

EH: I am not surprised. It is a clear indication that the powers that be do not want to reach an accommodation with the Palestinians. And Mr Bennett says that he wants to encourage the Palestinians in ‘bottom up’ economic development, through joint projects and so on. Mr Netanyahu said this some years ago. First of all, it’s a degrading term in itself, ‘bottom up’. It says you are on the bottom and we are on the top. Anyway, do we mean it? We have an entire city in the West Bank built by the Palestinians using money from Qatar and elsewhere. It’s called Rawabi. But it is uninhabited because Israel has not allowed water to be pumped into the city. Palestinians have made an enormous investment in it but for various bureaucratic reasons – and I am sure there are people who could talk for an hour about why this situation came about – we are not letting them get water. Period. Is this ‘bottom up’? They took their destiny in their own hands and built a city but we prevented them from occupying it.

And talking of dignity, the way that we are handling their finances is deplorable. We have frozen the money that we collect for them. According to the Oslo Agreement we collect duties and so on. We are trustees of this money. And we have decided because they have done this or that we are not giving them their money.

There was a famous British General called General Barker in WW2. He commanded the British forces in Palestine. He once said, ‘You should hit the Jews through their pockets.’ Everyone was up in arms and said ‘this is antisemitism!’ But what are we doing? We are doing exactly what General Barker suggested should be done to the Jews. Aren’t we?

It is terrifically enheartening to read this lucid interview with a man of great wisdom and experience. Can he make his voice heard in Israel ?