Fathom Deputy Editor Jack Omer-Jackaman, writing in a personal capacity, argues in favour of the US unilaterally recognising the State of Palestine. Such a move would be of largely symbolic value, he says, but importantly so. Crucially, ‘it would send two distinct messages to two distinct constituencies in desperate need of hearing them right now.’

When Paul Gross writes, I read; when he speaks, I listen. There are few Israelis I respect more. In opposing the possible unilateral US recognition of a Palestinian state as a step towards the two-state solution he supports, he puts the case better than anyone. However, and with respect for his reservations, I make the case here for immediate recognition, under certain conditions.

The objections to recognition are compelling in both practical and principled terms. It would signal an American attempt to strong-arm Israel into jump-starting a direct Israeli-Palestinian peace process which appeared clapped-out with the stillborn efforts of then-Secretary Kerry, before being bypassed during the Trump years and the focus on normalisation with Arab states during the Abraham Accords. The two are now being connected, with a US push for two states now tied to Saudi normalisation. (Paul thinks that process can withstand stasis on the Palestinian question – I see why but am with Michael Singh in being less sure.)

I understand why Paul and others might oppose this strong-arming. Peace processes need public buy-in and it is delusional to expect Israelis to be enthused by the prospect of a neighbouring sovereign Palestine not five months since one half of the Palestinian national movement conducted the worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust: five months in which the other, ‘respectable’ half has not found it within itself to offer a full-throated condemnation of the rampage of rape and murder. ‘How can this even be on the agenda,’ wrote Eran Hermoni, General Secretary of the Israeli Labor Party, ‘when Israel is still licking its wounds and mourning its dead?’

I understand these criticisms but favour recognition and the strong arm nonetheless. It is important to say that this essay is not a prescription for the actual substance of a two-state agreement, though it presupposes that such an agreement is both just and necessary (and if you care about both peoples, there is, as there has always been, no other solution). It is, rather, an argument for recognition as a necessary preliminary step of largely symbolic value. Crucially, it would send two distinct messages to two distinct constituencies in desperate need of hearing them right now.

To Palestinians: A Balfour moment

Some 138 nations already recognise the State of Palestine, including nine of the G20. Nonetheless, recognition from what remains, despite ubiquitous diagnoses of its imminent eclipse, the most powerful nation in the world, would be a genuine Balfour moment for the Palestinian national movement. It would represent, for them, the same acknowledgement the British afforded the Jewish people in 1917 – that they were a legitimate national people deserving of the same (then still emerging) rights to independent territory and self-determination as all national peoples, and bound by the same (also still emerging) obligations.

Such an acknowledgement is essential in a context in which the Palestinians’ opponents – in the Israeli government, in the pro-Israel international intelligentsia, and in the cesspit of the Twittersphere – will not let go of the lie that because Palestinian national identity was a late-emerging phenomenon it is somehow ersatz; that ‘a Palestinian’ is an oxymoron and that (s)he should be properly considered a Syrian, a generic pan-Arab etc. (See here for one example – noxious but no more so than many others; those who think it a Zionist shibboleth to deny Palestinian indigeneity might want to consider their hubris in believing they are right where Jabotinsky, by their lights, was in error.)

Recognition would reinforce to these Palestine-deniers: no, you are wrong, and it is official US policy that you are wrong. Israelis are right to demand that Palestinians accept the right of the Jews to a homeland in the Land of Israel – and acknowledgement of this should be a condition of recognition of Palestine. But the Palestinians require the same affirmation: that they are a distinct people, indigenous to the land, and that the free world considers a demilitarised Palestinian state a material and immutable inevitability, even if in abeyance.

Non-recognition lets the Palestinian leadership off the hook

The obligations conferred by recognition are as important as the rights. Recognition would also say: yes, we acknowledge that you are a state, now start to act like one, and not like a guerilla movement. Thomas Friedman was right here in claiming that in continuing a Paisleyite policy of never, never, never, ‘Israel is … relieving Palestinians of the burden and depriving them of the opportunity of recognising two nation-states for two people and building the necessary institutions and compromises to make that happen.’ Continuing to exist in an international state vacuum lets the Palestinians off the hook as well as denying them their rights. The cosmetic reforms attempted by the Palestinian Authority thus far, at US behest, are not even a start, of course, and the obligations on which recognition must be contingent should include a full-throated renunciation of the genocidal violence of Hamas and its fellow genocidalists from all factions of the PA, a commitment to their exclusion and suppression from the national movement, and an equally unambiguous recognition of the unimpeachable right of the Jews to a state in their historic homeland.

Recognition would also give the US and UK significantly expanded diplomatic capital. It would be affirmation for the Palestinians that their purported friendship is in earnest; that they do not dissimulate in their claims to being honest brokers and faithful friends in a conflict whose agony is as mutual as it is perpetual. When the time does come for substantive negotiation then, the Anglo-American hand demanding Palestinian flexibility will be strengthened. (US credibility in the region is not what it once was, by the way, so this is no small thing.)

A crucial injection of hope

Above all though, it would offer Palestinians hope, a commodity in despairingly short supply for generations now. Hope beyond the Gazan carnage. Hope that their misery – and yes, some of it has been self or leader-inflicted – is not destined to continue in perpetuity. Hope that the stasis of the peace process can be reversed. (But whose fault is the inertia, you ask, fairly. Who was it rejected Barak in 2001 and Olmert in 2008?) Hope, perhaps, that there remains a way beyond the way of the gun.

The long-term absence of hope is glaringly attested to both by data and the personal experience of anyone afforded the mixed blessing of visiting the West Bank. Palestinian mental health is among the poorest in the world, ‘with over half of Palestinian adults meeting the diagnostic threshold for depressive symptoms.’ And so is utter hopelessness the prevailing condition in, say, Hebron, where the multi-generational Palestinian malaise is both pungent and poignant. Some will balk at the comparison, but the sight of involuntarily idle Palestinians in the empty shell of the once-bustling Hebron market brings to mind Leon Pinsker’s imperishable description of the late 19th century European Jews as a ‘ghostlike apparition of a living corpse, of a people without unity or organisation, without land or other bonds of unity, no longer alive, and yet walking among the living.’

Hope is sorely needed, not least to inspire a new generation of moderate leadership, and will only come from a substantive alteration of Palestinian national circumstances. Ordinary Palestinians need to be able to believe in whichever process is to follow whatever final outcome emerges from a truly horrific war in Gaza. A reformed technocracy presiding over the same stateless entity, even if unified, will not cut it. (And unified it must be, recognition also signalling that the symbiotic divide-and-rule era of Netanyahu-Hamas is over.) I admire Salam Fayyad tremendously, but his un-sexy brand of state building didn’t cut through the cult of martyrology before and it won’t now; at least not alone. Similarly, a Gaza Strip of the type Netanyahu’s adumbrated post-war ‘plan’ envisages is a de facto Israeli re-occupation and a breeding ground for mass resentment and the revitalising of Hamas. (It is a recipe for southern Lebanon 1982-2000, in fact.)

Such Palestinian hope is also a valuable Israeli security asset. We know well that the notion that hopelessness is the cause of Palestinian violence is simplistic. But to deny that is a factor is no less an error. The long-term rationale of the military and security establishments in favour of allowing West Bank labourers into Israel is testament to it: terrorist recruiters are malevolent succubae, feasting on the despair of the hopeless and under-occupied. So too, while Israelis might justly point to the lamentable Palestinian Authority’s failure to clamp down on rejectionist extremism (with ‘pay for slay’, to encourage it, in fact), the absence of hope rears its ugly head here too. The whole logic of the introduction and support of the PA Security Forces during Oslo was based on a quid pro quo: that effective internal policing of the wreckers would lead to statehood. Remove the carrot from that equation and you have been left with a demotivated rump force whose only real remit is prolonging a politically bankrupt and kleptocratic President Abbas. It is little wonder their control has slipped so drastically and that jihadi elements have flourished.

I hear the chidings of my Israelis friends – that hope is for those who put their house in order first, and that I am putting the cart before a pretty lame horse. I encourage them to consider reversing the equation; that moderation presumes and requires hope, rather than what Victor Serge called, in another desperate place in another desperate epoch, a hellish ‘world without possible escape’. Israelis and their friends like to think that recognition of Israeli rights and renunciation of violence should need no carrots, but they do. Similarly, the idea that nations must not be born in fire or midwifed by violence is frankly naïve: they should not, but they almost always are. It must not be – and I do not think it is – that the evil of 7 October brought us to the recommendation made here; but it may well be that it is the carnage that has followed in Gaza that does so.

Living with irony

All of this exhorting to hope of course rests upon the assumption that 1) a majority of Palestinians, and the Palestinian national movement, care more for a prosperous and independent future than for a fully revanchist erasure of Israel; and 2) that the forces who undoubtedly do not can be adequately vanquished or marginalised. About the second, time will tell. About the first I am not naïve as to how deep the rot goes and accept that nothing short of a collective Palestinian mental-spiritual revolution will fully accomplish conditions necessary for a lasting peace.[1] (An Israeli version is surely required too, incidentally.) But nor am I prepared to indulge the notion, de rigeur, that an entire people can be written off and kept chained outside the community of nations like a dangerous dog. Collective post-7 October trauma of an extent I will never be able to adequately imagine does not excuse the volume of dehumanisation of all Palestinians I have seen since 7 October, including from those who should know better, who are better. Like Burke, ‘I do not know the method of drawing up an indictment against a whole people,’ and responsible western diplomacy requires simultaneously thinking the very best and very worst of the Palestinians, and living with the contradiction.

I accept that such a gamble is beyond most Israelis, and am not certain that a Palestinian volte-face would be likely under even the most felicitous circumstances. But I am quite certain that one will never come as long as cynicism and despair rule and Palestinians can see a future only of interminable occupation. For here are two ironies, in a conflict tragically full of them: we do not know if the Palestinians can ever fully free themselves (and their Israeli victims) from the cult of martyrdom; we do know that such a liberation is only possible if they are offered – and are prepared to grasp – the right to dreams beyond martyrdom. Similarly: the fear that Palestinians can never abandon the cults of revanchism and antisemitism and thus cannot be afforded a state collides with the undoubted reality that they will most certainly never abandon them as long as they are stateless.

To Israelis: Shifting the Veto Paradigm

Unilateral recognition is also necessary in removing, or rather moderating, the prevailing Israeli veto over Palestinian statehood; in sending a message that statehood is neither a preventable hypothetical purely in Israel’s gift, nor a can to be kicked indefinitely down the road. To shift the veto would not be to tie Israel’s hands unreasonably in future final status negotiations, nor to force it to accept iniquitous or suicidal conditions. Borders, the right of return, Jerusalem – all would be subject to bilateral agreement between the parties, and not preconditioned by recognition.

Why does this veto need to change? Firstly, because it is the height of disingenuousness to condemn only the Palestinians, and never the Israelis, for failing to internalise the justice of two states.

Let us imagine that Israeli opposition to two states was based solely, and in good faith, on security: that Israel was otherwise highly desirous of two states for two peoples. In that case, an Israeli veto would be fine, and I would back it, because it would be guaranteed that it was, aspirationally at least, temporary. This may indeed be the position of much, even a majority, of the Israeli people. But as a political prospect it is fantasy. There is another plank to Israeli rejection – an exceptionally powerful one on which any government of the right depends. Witness Simcha Rothman MK, judicial reform architect and influential voice on the Israeli new right, speaking last week:

Judea and Samaria belong to the Jewish people, irrevocably, by international law, which many like to ignore. The same is true of Gaza … Irrevocable international commitments have been made to the ancient Jewish people for the western Land of Israel … So Israel does have ‘veto power’ over establishing a Palestinian state in the western part of The Land of Israel, for the same reason that any home-owner in the world has ‘veto power’ over her or his own living room.

We might scorn Rothman his historical illiteracy, but he is to be congratulated for his candour: no two states, ever. Tell me, please, how this is any less inflexibly, dehumanisingly irredentist than Hamas speaking of the occupied city of Tel Aviv? The Palestinians could (extremely hypothetically) lay down their arms entirely and pledge undying brotherhood with the Jewish state, and still the Rothmanite veto should be employed.

Nor is his a minority voice: he speaks here, albeit more explicitly than most, for the whole spectrum of the Israeli right as it has become – from Netanyahu’s Likud, hollowed-out of the Beginite pragmatists, to Ben Gvir’s Jewish Power. The extreme right has been well and truly mainstreamed and is an essential part not only of any Likud coalition but of the Likud itself. The presence of Likud MKs and ministers at January’s horror-show ‘Conference for the Victory of Israel’ at Jerusalem’s Binyanei Ha’uma was undoubtedly noted with alarm in Washington. As were the affirmations of the Jewish right to all the Land of Israel and calls for the transfer of Palestinians. (It was Likud minister Shlomo Karhi who dropped the Orwellian nugget that the transfer should, of course, be voluntary, but ‘“voluntary” is at times a situation you impose [on someone] until they give their consent.’)

Join me on a thought experiment: let us just imagine that Barghouti is freed from jail and combines his tough-guy iconography with proving in earnest about peace and two states (stay with me, I told you it was a thought experiment). He allies with Dahlan and Fayyad. Together they embark, with CIA assistance, on a campaign of state building and a purging of the jihadists and other rejectionists. They command an absolute monopoly on the internal means of force and violence and speak for the Palestinian national movement in one voice. They are ready for a demilitarised state on the lines of Olmert and Abbas. In other words, the security concerns on which two states are pre-conditioned are as met as they are ever likely to be. Are we to imagine that Israeli currents as diverse as Netanyahu, Ben Gvir, Lieberman, Bennett, and Deri say ‘sure, we’re in?’ The idea is preposterous.

There are thus currently two inevitable Israeli vetoes, not the one defensible one. One is a test the Palestinians can pass or fail, conceivably at least, on their terms. The other they fail simply by clinging stubbornly to their land and identity. It is this second indefensible veto which shatters the logic of the traditional Israeli insistence that the process run as follows: renunciation of violence and recognition of Israel > two state negotiations > statehood. This rationale depends upon an Israeli leader being able to enter the second stage prepared to make the kind of concessions Olmert made to Abbas in 2008 (and which Abbas unconscionably spurned). In the intervening years this spirit of compromise has vanished utterly from the table, in favour of jihad and pay-for-slay on the Palestinian side and of ‘conflict shrinking’, potential annexation, and stasis on the Israeli. A fait accompli move like recognition, then, is a firm signal that the Rothmanite veto is invalid; a firm signal too that the Israelisation of the West Bank (let alone a re-settling of Gaza) whether through annexation or a continuation of the present, lawless settler state, is no longer merely impotently frowned upon but opposed with genuine consequence. UK-US sanctions on violent settlers, if a little ham-fistedly managed, were a welcome step, as was Blinken’s reversal of the Pompeo doctrine.

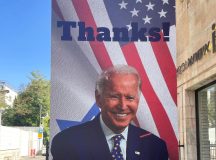

The changing face of Israel’s liberal allies

All this is, I recognise, spectacular chutzpah on mine (and Biden’s) part. But this is the way the wind is blowing for friends of Israel like us who ally a commitment to its people and its security with an insistence on something like justice for the Palestinians. With this war, something has irreversibly shifted, and the journey leading towards two states – if not its final resolution – can be deferred no longer. I might not go as far as the great David Grossman, who wrote recently in the New York Times that ‘this is a rare moment when a shock wave like the one we experienced on Oct. 7 has the power to reshape reality. Do the countries with a stake in the conflict not see that Israelis and Palestinians are no longer capable of saving themselves?’ But I do advise sceptical Israelis of the wisdom of Yair Hirschfeld, in a recent edition of Fathom:

We Israelis have to understand that the US-Israel Relationship remains fundamental and that if we do not ‘go with the tide’, the tide will go against us … This does not mean that Ukraine or Israel have to blindly accept a US diktat. But it does require that our strategic dialogue should be pursued within the well-defined strategic framework, laid out and defined by President Biden and his administration.

It is not quite ‘get on the peace train or get left behind,’ but it is perhaps not far off.

Some are optimistic that a future Prime Minister Gantz would be much more open to progressing two states – a hope I do not share quite so fulsomely. More open certainly, but to any great significance? I doubt it. Leaving it to Bibi or his successors, then, is to promise another generation’s worth of agonising inertia. Absent a move like recognition nullifying this branch of Israeli rejectionism, and absent an Israeli revolution on an anti-judicial-reform-scale defeating it internally, there is a danger that belief in the two-state solution becomes akin to a belief in fairies, surviving on the faith of the credulous alone.

The temptation of course will be to dance around Biden until the great orange hope returns, but this would be the flimsiest of sticking plasters. The nation of Palestine exists; the state of Palestine must soon exist: it is reasonable and necessary to act accordingly.

[1] There is at least some evidence that Palestinian rejection of violence and support for the ‘two states for two peoples’ way of peace correlates with belief in its feasibility. In December 2023, alongside the horrific headline-grabbing figure of 72 per cent support for Hamas’s launching of the 7 October pogrom, polling showed 65 per cent of Palestinians believing that a two-state solution is no longer practical due to settlement expansion. (See https://www.pcpsr.org/sites/default/files/Poll%2090%20English%20Full%20text%20Dec%202023.pdf) Support for the attacks also coincides hugely with a refusal to believe that they included the rape and massacre of civilians. (See ibid) In the abstract, the vast majority of Palestinians believe that the murder of women and children is not permissible (see ibid, p.6). Pessimism regarding the prospects for a negotiated two-state solution do indeed lead to a correlative increase in a preference for armed struggle. ‘When asked about the best way to end occupation and establish an independent state, the public was divided into three groups: a majority of 63 per cent (68 per cent in the West Bank and 56 per cent in the Gaza Strip) said it was armed struggle; 20 per cent said it was negotiations; and 13 per cent said it was popular non-violent resistance.’ (See ibid) Compare this to polling of the Palestinians in March-April 2000, two/three months prior to the Camp David summit. Then, 71 per cent of Palestinian supported the peace process, and a narrow plurality opposed armed attacks against Israelis (both the Islamists and the ‘Palestinian Mandela’ Barghouti soon had other ideas, of course). A plurality also expected the peace process to lead to the establishment of a Palestinian state in the near future, with a comfortable majority optimistic about the future of the Palestinian people. (See https://www.pcpsr.org/en/node/500). Similarly, the oft-repeated objection that Gazans voted for Hamas in 2006 and so voted for rejection and perpetual violence does not necessarily stand scrutiny. ‘Why did Palestinians back Hamas in 2006? An exit poll showed that electors voted for Hamas despite its absolute hostility to Israel. 80 per cent wanted peace with Israel; 75 per cent wanted Hamas to change its attitude towards Israel. But 78 per cent believed Hamas would act against corruption and 68 per cent thought Hamas would act to stamp out criminality and disorder.’ (See https://www.workersliberty.org/story/2024-01-09/hamass-record-power-gaza#:~:text=80%25%20wanted%20peace%20with%20Israel,power%20was%20venal%20and%20incompetent.)